FC105AThe Start of the French Revolution (July, 1789- July, 1790)

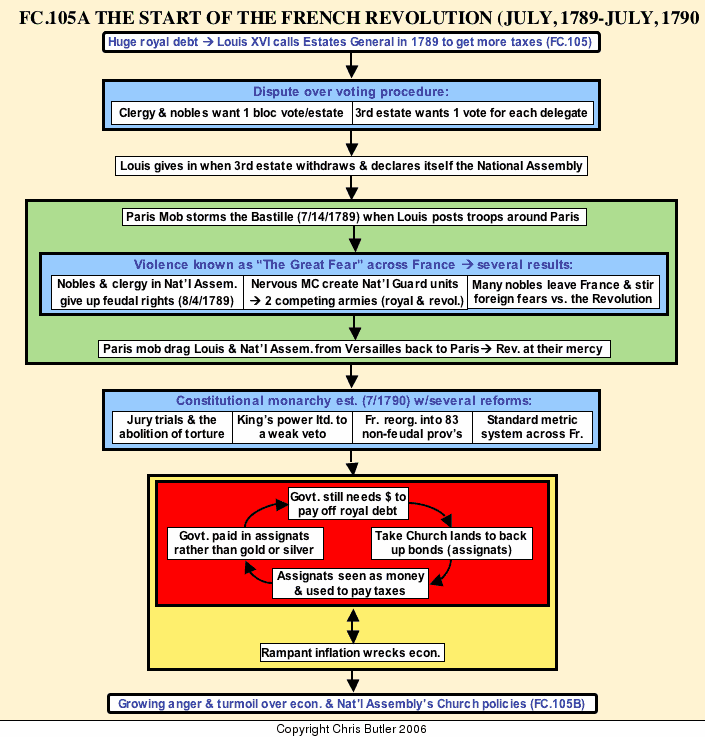

Hopes ran high for widespread reforms when Louis XVI called the Estates General to Versailles in the spring of 1789. While Louis' main concern was to get more taxes to cover France's mounting debts, the delegates from the Third Estate (mostly middle class lawyers and businessmen) came with notes ( cahiers) from their constituents urging such reforms as taxing the clergy and nobles to even the tax burden. However, before these issues could be addressed, a more basic problem arose: voting procedure.

The First and Second Estates (clergy and nobles respectively) wanted bloc voting where each estate's votes collectively counted as one vote. This would give the nobles and clergy two votes to one for the Third Estate (representing the middle and lower classes who comprised 98% of France's population). Therefore, the Third Estate, whose delegates equaled the combined number of noble and clergy delegates, wanted one vote per delegate. Since a number of liberal clergy and nobles would probably vote with the Third Estate, this would give the Third Estate an effective majority of votes.

The decision belonged to Louis, whose weak and indecisive nature let matters get out of control. On June 17, the Third Estate, seeing the king's indecision, put pressure on him by withdrawing along with many poor delegates from the clergy and declared themselves the National Assembly with the exclusive right to grant taxes. When Louis locked them out of the Assembly Chamber, they withdrew to an indoor tennis court and took what became known as the Tennis Court Oath, vowing never to separate until they had formed a constitution. Somehow, a meeting about taxes had turned into a movement to form a new government. On June 27, Louis gave in and ordered the First and Second Estates to merge with the National Assembly. The Revolution had begun.

Two weeks later, on July 10, Louis, under pressure this time from the nobles, ordered troops to surround Paris and Versailles. The next day he fired a popular finance minister, Neckar, who had advocated taxing the nobles. These acts, plus continued food shortages triggered demonstrations in Paris that culminated in the storming of the Bastille (7/14/1789), an old prison with so little value that Louis himself had plans for tearing it down. Despite this, the Bastille was a symbol of oppression and its storming has been celebrated ever since as France's Independence Day.

All across France the Bastille's fall touched off the Great Fear, waves of violence in which armed bands of peasants killed nobles and royal officials, burned chateaus, and destroyed records of feudal obligations. This created several effects. First, concerned property owners in cities throughout France took the lead from Paris and formed their own National Guard units to protect themselves and their property. As a result, France now had two armies: the king's royal army and the revolution's National Guard. Also, the mounting violence and chaos started a wave of nobles emigrating to other countries. Successive waves of emigration would bring stories of ever mounting turmoil in France that would stir up foreign fears, hostility, and eventually full scale military attempts to overthrow the revolution. The resulting wars would rage across Europe for a quarter century.

Finally, fear of violence also seems to have affected the National Assembly. On the night of August 4, 1789, nobles and clergy surrendered their feudal rights and privileges in a remarkable show of generosity (or fear). In one fell swoop, feudalism had been abolished in France, although the final draft of the document did give compensation to the nobles and clergy and delayed dismantling the feudal order.

In much the same spirit, the National Assembly issued the "Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen" (8/27/1789). This remarkable document declared for all men, not just Frenchmen, the basic ideals of the revolution: liberalism (the belief in civil and political rights and liberties for all men) and nationalism (the belief that a people united by a common language and culture should control its own destiny). These two principles have proven to be two of the most powerful ideas in modern history.

Center stage now moved back to the Paris mob of laborers and small shopkeepers, known popularly as the sans culottes from their wearing long pants rather than the more fashionable short breeches (culottes) of the upper class. Partly inspired by the Great Fear and the acts of the National Assembly, but even more by continued food shortages, they marched on Versailles and brought the king and National Assembly back to Paris to ensure they would relieve the suffering of the urban poor. From this point on, the sans culottes would exact an ever more powerful and radical influence on the French Revolution, a power and influence far out of proportion to their numbers.

However, the Revolution at this point was still a fairly mild and civilized affair controlled by moderate middle class delegates. It was the enlightened ideas of such philosophes as Rousseau and Voltaire plus the growing need for reforms, not pressure from the sans culottes, that mainly influenced the constitutional monarchy they established in July, 1790. Power mostly resided in the National Assembly, with the king having only a weak temporary veto on its actions. In order to weaken old feudal loyalties, France was broken up into 83 new provinces known as departements, the basis of France's administration to this day. Jury trials were established, torture was outlawed, and a more humane form of execution, the guillotine, was introduced. Internal tolls were abolished, and a standard system of weights and measures, the metric system, came into use. The new constitution definitely had a narrow middle class bias, as seen by its measures to improve trade plus its property qualifications for voting that shut out all but 4,000,000 Frenchmen from full citizenship. It was a combination of the new government's more progressive measures and shortcomings that would lead to more radical reforms.

One problem the National Assembly did not solve was the huge royal debt that had started the revolution in the first place. Since the king was kept as constitutional figurehead of the government in order to make it look legitimate, the National Assembly could not repudiate the royal debt and still seem credible. Therefore, it came up with one of the more innovative policies of the revolution: confiscation of Church lands, the value of which would back up government bonds called assignats. The National Assembly originally sold 400,000,000 francs worth of assignats to pay off its most urgent debts.

Unfortunately, many people saw the assignats as money and used them rather than hard cash to pay their taxes. As a result, the Government, finding itself still in need of cash, issued more assignats and the cycle started all over. There were two main results of the government's Church policies. First of all, the flood of assignats triggered an inflationary cycle that destabilized the French economy and political structure. By the end of the revolution, the assignats were only worth 1% of their face value. Second, many people were angry over the state's control of the Church that extended to electing priests and making them swear a loyalty oath to France. Both of these would combine to unleash forces making the revolution more radical and violent.