FC130BThe Communist Dictatorships of Lenin & Stalin (1920-39)

Lenin’s Rule

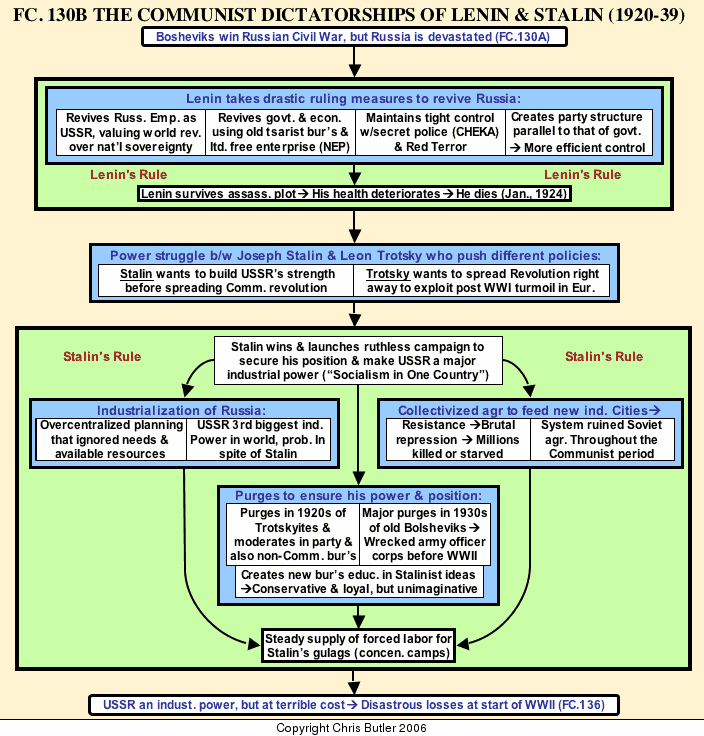

After the devastation of World War I, the Revolution, and Civil War, Russia was a total wreck. Factories were in ruins and half the working class gone, either dead or returned to the farms. Millions had died, mainly from the famine and disease accompanying war. Two million more, mostly nobles, middle class, and intellectuals, had emigrated to other countries. Now it was up to Lenin to restore some degree of prosperity and order. There were four main policies he followed, one that loosened his control for the time being and three that tightened his control.

Lenin eased up a bit with his New Economic Policy (NEP), which allowed some degree of free enterprise to encourage higher production by the peasants. While Lenin had little choice but to let free enterprise return, he could also justify NEP in Marxist terms since, according to Marx, Russia would have to evolve through a capitalist phase before it was ready for Socialism. For several years in the 1920’s, Lenin’s Russia saw widespread experimentation in the arts and social engineering as well as economics. Cubist and futuristic art flourished. Avant-garde theater featured acrobats as well as heavy political messages. The family was also under attack as a bourgeois institution with women as the oppressed working class. Therefore, women gained equal rights and pay as well as access to easier divorces and legalized abortions. Some young communists even saw free love and public nudity as revolutionary acts of liberation from bourgeois values. Older Bolsheviks frowned on such acts, but tolerated them in the spirit of creating a new socialist society. Lenin made similar concessions in government, giving tsarist bureaucrats and technical experts more authority in running the government and factories since most communists were uneducated and untrained in the technical expertise needed to run a country.

However, this is not to say that Lenin relinquished any political control over Russia. For one thing, the old non-Russian provinces of the tsarist empire were brought back under tighter control, the rationale being they needed Russia’s help in establishing a socialist paradise more than they needed national independence, which would be irrelevant once the workers’ revolutions had swept the globe. Of course, to these subject peoples, this new Soviet Union looked suspiciously like the empire of tsarist Russia.

Lenin exerted greater control over local governments through the Communist Party. One problem he had from the earlier days was that the local soviets had seized control of local governments. Although the Bolsheviks themselves had used the slogan, “All power to the Soviets” and could do little to control the soviets during the crisis of the civil war, Lenin was determined to eventually get tighter control on local matters. What he did was create a party structure parallel to that of the government. The local party officials were much more tightly controlled than the soviets and correspondingly more efficient in carrying out Lenin’s directives. As a result, control of the Communist party was as important for the rulers of the Soviet Union as was control of the government as a means for ruling the country.

Finally, Lenin, like Marx, felt the workers could not achieve true revolutionary consciousness on their own, but needed a strong centrally directed party of Marxists to lead them to socialism. Therefore, he had to resort to what he called “Proletarian dictatorship” to ensure the workers got what they deserved. However, this was not rule by the working class, but rather rule by the Communist party with working class members in it. Of course, Lenin strictly ruled the party, thus theoretically making his will that of the party and the people. Enforcing “proletarian dictatorship” and the “Red Terror” was the CHEKA (the All Russia Extraordinary Commission for Combating, Counterrevolution and Sabotage). This was Lenin’s secret police, except that it was much larger, more effective, and deadly than the Czar’s secret police had ever been.

The harsh and autocratic nature of the Soviet system that emerged was influenced by several factors. First, there was the dictatorial nature of Lenin’s personality that largely determined the course of the revolution. Second, there was a certain continuity from the tsars’ absolutist regime to Communist rule. Finally, many more Communists had joined the party during the revolution and civil war than before 1917. As a result, they saw the revolution in military terms as a sort of brotherhood in arms, and it assumed a military aspect with party members wearing military uniforms and using military jargon for political offices and concepts.

However, before Lenin could enact a thorough program of reform in the Soviet Union, he died in 1924. He was a brilliant leader and sincere revolutionary who oftentimes ignored human feelings in pursuit of his Communist revolution. His harsh measures must be seen in light of the harsh conditions that demanded them if the Revolution were to survive. Lenin is remembered as the father of the Revolution, but his early death left to his successor, Stalin, the job of carrying out the real revolutionary transformation of Russia.

Stalin’s revolution (1924-40).

Lenin’s death led to a power struggle between Leon Trotsky, the creator of the Red Army during the Russian Civil War, and Joseph Stalin. Stalin was one of the few real working class members of the Communist party’s upper ranks. The name Stalin, meaning “man of steel”, reflected his willingness to take on jobs no one else wanted, gathering a lot of power into his hands in the process. He was also a cold and ruthless politician who managed to squeeze out the more intellectual Trotsky. Not content with a mere political victory, Stalin’s agents later tracked down Trotsky in Mexico and murdered him in 1940.

While Trotsky had wanted to focus on spreading the Communist revolution worldwide, Stalin wanted to concentrate on building up the Soviet Union internally first. He felt a need for a revival of the revolutionary spirit since many Communists thought Lenin’s NEP had steered Russia away from a true socialist society. His first step was to purge the moderate wing of the party that still wanted to continue Lenin’s policies. Among his victims were the middle class and non-Communist bureaucrats and technicians that Lenin had relied upon to keep the state and economy working. While this was popular with the more radical Communists, it also deprived Stalin of the very people he needed to develop Russia’s industries. Stalin then launched a campaign to build the Soviet Union into a great power. His program had three parts: the transformation of the Soviet Union into an industrial power, collectivization of the farms in order to support the populations in the new industrial cities, and a purge of any elements Stalin suspected of disloyalty.

Stalin’s industrialization was carried out in a series of Five Year Plans where the government set projected goals for economic growth. However, the first Five Year Plan (1928-32) in particular was as much political rhetoric as economic planning, which seriously hampered efforts to meet its goals. For one thing, human and material resources were not adequately figured into the plan, causing constant confusion and work stoppages. However, at least officially, each of Stalin’s Five Year Plans more than met their goals. How much of this was the truth, Stalin lying to the world, or nervous officials lying to Stalin is hard to say. There were harsh penalties, even executions, for officials failing to meet their quotas, thus providing strong incentives to meet their quotas by padding their figures or even sabotaging each other’s efforts.

Whole new cities and even lakes appeared where none had existed before, many of them named after Stalin himself. Oil production trebled, while coal and steel production rose by a factor of four times. Stalin also established a massive system of public schools and universities to provide a literate (and more easily brainwashed) work force as well as engineers for his factories. By 1940, the Soviet Union had an 85% literacy rate and was the third largest industrial power in the world behind only the United States and Germany.

However, this was done at a price. For one thing, Stalin concentrated on heavy industries, such as steel, electricity, and heavy machinery, and consequently ignored the production of basic consumer goods, including even housing, for his people. He also used virtual slave labor by taking millions of peasants and others whom he saw as threats to his regime and using them in building his massive canal, hydroelectric dam, and factory projects. Thus millions died for Stalin’s dream of an industrial state.

Collectivization of the agriculture was mainly a means to an end: to produce enough food to support an urbanized industrial society. Marxist doctrine forbade private property, and Stalin, wanting as much centralized power as possible, used this principle to gather the farms into giant state-run operations. In theory, organizing the farms along the lines of industrial factories should increase productivity enough to support the Soviet Union’s new industrial cities. However, there were several flaws with this. First of all, such a scheme demanded a level of mechanization far beyond the Soviet Union’s capacity, which, at that time, still had 5.5 million wooden plows in use. Also, Stalin failed or refused to recognize that people work harder if they feel they are working for themselves instead of a landlord, even if that landlord is the state. Since many peasants had gained possession of their own land before and during the Revolution, collectivization met with strong resistance from these landholders, known as kulaks, and that led to untold troubles.

Stalin saw the kulaks as traitors to the Revolution and launched an all out campaign against them. Police and soldiers surrounded villages and hauled the peasants off to collectives, labor camps (which provided slave labor for Stalin’s industrial projects), or mass executions. Collectivization was also a disaster for Soviet agriculture and its people. Peasants burned their own grain and butchered their livestock to keep them out of government hands. That and the disruption caused by Stalin’s harsh policies led to widespread famine that killed millions more. Any gains Soviet agriculture may have made were probably in spite of Stalin, not because of him. This brings us to the third feature of his regime, the Stalinist terror.

Stalin was an extremely paranoid man who easily imagined both that anyone not meeting his expectations of performance was a traitor to the state and that anyone exceeding his expectations was an ambitious conspirator against him. In 1936 Stalin purged a wide range of people whom he saw as traitors or threats to his regime: government officials, military officers, old Bolsheviks, and teachers in addition to kulaks and inefficient factory managers.

The trials of these people were an absolute farce, where the accused were forced to read contrived confessions of their alleged crimes against the state before being sent to Stalin’s labor camps, providing much of the slave labor needed for Stalin’s industrial projects. However, the purges did great harm to Russia. Besides stifling initiative and poisoning society with an element of fear, they also eliminated most of the Red Army’s top officers, replacing them with men who were inexperienced and subservient to Stalin. Russia would pay a terrible price for this in World War II.

Those replacing the bureaucrats and engineers eliminated by Stalin’s purges were young men from working class backgrounds educated in the new schools and universities established by Stalin. Instead of the radical and somewhat independent-minded Bolsheviks in military uniforms agitating for more revolutionary reforms, Stalin now had an elite corps of educated engineers and bureaucrats loyal to him and more concerned with technical matters and industrialization than factional politics, Marxist ideology, and loyalty to a fighting Marxist brotherhood. Instead of uniforms and eccentric cultural ideas, they wore suits and attended classical concerts and ballets. They were the products of the revolution, but they were hardly revolutionary themselves, being prone to conserving the gains made by their party rather than pushing toward new frontiers. Stalin’s two successors, Khruschev and Brezhnev, both came from this generation and reflected its more conservative tendencies. The revolution had come full circle.

Regardless of the cost, the 1930’s saw the Soviet Union emerge as a major power, which seemed all the more remarkable since the rest of the world was mired in the Great Depression. This provided great publicity for Communism when resurgent Russia was compared to the ailing capitalist world. Communist membership grew in the western democracies, while a number of poorer countries adopted their own five-year plans in imitation of Stalin’s “socialist miracle”. All of these underscored the fact that the 1930’s were a time of great economic hardship, which led to rising political tensions and eventually World War II.