The Islamic WorldUnit 6: The Islamic World

FC46The rise of the Arabs & Islamic civilization (632-c.1000)

The sweep of Empire (632-750 C.E.)

The death of Mohammed shocked many Arabs who had attributed divine qualities to the prophet. In order to ease their doubts, one of Mohammed's chief followers, Abu Bakr, addressed the crowd gathered in Mecca: "Whichever of you worships Mohammed, know that Mohammed is dead. But whichever of you worships God, know that God is alive and does not die." Then he quoted a passage from the Quran: "Mohammed is a prophet only; there have been prophets before him. If he dies or is slain, will you turn back?" Their nerves soothed and their faith reassured, the Arabs struck out on a path of conquest almost unparalleled in its scope and speed.

The civilizing influences filtering into Arabia from Rome and Persia had two effects combining to give the Arabs the dynamic energy for conquering an empire. For one thing, those influences made Arabia fertile ground in which Islam could take root. Second, they helped the Arabs to unify and expand outward, especially when inspired by Islam, whose warriors believed that death in a holy war for the faith led to being transported instantly to Paradise. Add to this very capable leaders armed with the lightning fast tactics of the desert, and Islam's armies became the most potent forces of their day.

Two other outside factors also made the Arabs' rapid expansion possible. First, there was the degree of support, or at least non-resistance from the many Aramaic speaking peoples under Roman and Persian rule, since they felt much closer kinship to the Arabs than to their rulers. Also the Muslims were tolerant of Christians and Jews, charging only a special tax instead of forcing them to convert. This contrasted sharply with the harsher Byzantine policies against the Monophysite Christians in Egypt, Syria, and Palestine. The second factor was timing. Both the Byzantine and Persian Empires were worn out from years of prolonged warfare against each other. Likewise, Visigothic Spain was suffering internal decay and was thus ready for a fall.

The Arabs' first victims were the Byzantines and Persians. At the Yarmuk River in Palestine they were facing a large enemy force when a sandstorm blew up in the Byzantines' faces. Taking this as a sign from God, the Arabs charged and destroyed the Byzantine army. Syria and Palestine, along with Jerusalem, a city Muslims also revere, fell into the Arabs' hands. The Patriarch of Jerusalem, resplendent in his finest robes, had to meet this rag tag army of desert nomads and personally lead their leader's horse into the city. Nothing could better symbolize the contrast between the wealthy civilized subjects and their new masters fresh out of the desert.

The Arab advance continued northward into Asia Minor toward Constantinople, a particularly prized goal for Muslims. Despite their desert origins, they rapidly built a navy (with the help of their newly conquered Greek and Phoenician subjects) with which they twice besieged Constantinople (674 and 717). In each case, the Byzantines' dreadful new weapon, Greek fire, helped save the city and empire. The Byzantines held fast, and a fairly stable frontier between Christianity and Islam gradually took shape in Asia Minor.

Sweeping westward the Arabs took Egypt with an army of only 4,000 men, following quickly with the conquest of North Africa. In 711 C.E., a small Muslim force crossed into Spain, where the Visigothic kingdom also crumbled before its onslaught. Storming into southern Gaul (France), the Arabs were finally stopped by the Franks at the Battle of Tours (733). Eventually a stable frontier formed in northern Spain between the Muslim and Christian worlds.

The Arabs also advanced eastward into Persia, which, also exhausted by prolonged war with the Byzantines, collapsed like a house of cards in 651. However, Persian culture would re-emerge as a major influence on Islamic civilization as it developed. In 711 C.E. (the same year Muslim forces entered Spain), the Arabs entered northwestern India and started to establish their power there. They also extended their rule into Central Asia and beat a Chinese army in a battle near the Talas River, which brought the Arabs a new type of product, paper, and helped establish Islam as the dominant religion in Central Asia. Thus, by 750 AD, after little more than a century, the Islamic Empire stretched from Spain in the west to north India and the frontiers of China in the east, the most far-flung empire of its day.

Adapting to empire

In the year 640, a messenger brought news to the Caliph Omar in Mecca that his forces had taken Alexandria with its 4000 villas, 4000 baths, and 400 places of entertainment. To celebrate this victory, Omar had the messenger share a meal of bread and dates with him, the simple fare of desert nomads. However, as ill suited to ruling such an empire the Arabs may have seemed, contact with their civilized Persian and Byzantine subjects allowed them to adapt quite quickly. They had three things to do: decide who was to rule, set up a system of government to rule the empire, and absorb and adapt the older cultures they ruled to Islam.

The ruler

The first problem was who should be caliph, the spiritual and secular successor to Mohammed. The first four caliphs were elected by a tribal council of elders and are referred to as the Orthodox Caliphs, ruling from 632 to 661 C.E. However, as the empire grew, this form of government became increasingly inadequate. In addition, tribal and clan jealousies continued. Of the four Orthodox Caliphs, only one, Abu Bakr (632-634) died a natural death. Finally, the Umayyad clan took over and established the Umayyad Dynasty (661-750). From now on, the dynastic principle of one family choosing the caliph would dominate.

However, not everyone saw the Umayyads as rightful rulers. Some known as Shiites felt that only descendants of Ali, the last Orthodox Caliph and a member of Mohammed's family, should be caliph. Those who felt any Arab could be caliph were known as Sunnites. The Sunnite-Shiite split is still one of the major factors dividing the Muslim world today.

In 750 C.E., a revolt led by Abbas, a governor of Persia, overthrew the Ummayads and established the Abassid Dynasty (750-1258). Abbas was a ruthless man who worked to exterminate the Umayyad clan to a man. He even invited eighty Umayyads to a banquet and had them murdered at the table, then covering the bodies so he could finish his meal in peace. One member of the clan did survive, Abd-al-Rahman, who barely escaped Abbasid agents to make his way across the Mediterranean through the use of disguises and trickery. He arrived in Spain and founded an independent Umayyad dynasty. This was the first crack in the unity of the Islamic state. It would never be unified again.

Ruling the empire

From the start, the Umayyads saw that they must adapt Byzantine and Persian techniques for ruling their empire. Therefore, they instituted some major changes. They moved the capital from Mecca to a much more central location, Damascus in Syria. They created the first Muslim coinage. They also adapted Byzantine and Persian bureaucratic methods as well as the Persian system of relay riders for faster communication of news from the further parts of the empire.

The Abbasids continued Umayyad centralizing policies. Consequently, more and more Persians, Greeks, Jews, and other non-Arabs gained positions of responsibility, since they had the training and experience necessary for running the government. This signified more equality and less distinction between the Arab conquerors and their subjects, especially for those non-Arabs who converted to Islam. Even the Abbasid caliphs had less and less Arab blood in them, since few of them married Arab wives.

Nothing better shows these changes in Muslim government than the position and status of the caliph himself, which was modeled after the Persian concept of kingship. Although he still tried to advertise his religious functions by wearing the tattered robe of Mohammed upon occasion and styling himself as the "Shadow of God on earth", he was no longer a simple man of the people. Just getting an audience with him involved dealing with a multitude of officials. Upon approaching the throne, one prostrated himself, while the caliph remained out of sight, speaking to people through an elaborate screen that hid him from view. An executioner with drawn sword reminded one of the need to behave according to the strictest rules. This contrasted sharply with the Caliph Omar sharing his bread and dates with a messenger.

Exalting the caliph and keeping him hidden from view also isolated him from his people and the problems of his empire. As a result, the vizier, or prime minister, assumed more power and became the power behind the throne for the generally weak or disinterested caliphs. Later, mamelukes, slave bodyguards, also gained increasing power, virtually holding the caliph as a prisoner in his own palace.

Symbolic of the great changes going on in Muslim government and culture was the new capital the Abbasids built: Baghdad. Just as Constantinople was the crown jewel of the Christian world, so Baghdad became the same sort of gem for Islam. Its site in Mesopotamia was flanked by the Tigris River and various canals, thus making it easy to defend. Its central location also put the government in closer communication with the empire's far-flung provinces.

The form of the city shows the growing influence of Persian culture at court. Its layout was round in the Persian style, and had three sets of surrounding walls. The middle wall was the tallest, supposedly being 112 feet tall, 164 feet thick at the base, and 46 feet thick on top! Two highways split the city into four quadrants, each with a central market. The central part of the city was dominated by a great mosque and the caliph's palace, which was made of marble with a golden gate and a massive green dome 120 feet in diameter. On top of the dome was a statue of a lancer. According to legend, this statue would point toward parts of the empire where there was trouble. Baghdad was supposed to be inhabited mainly by the caliph, his court, and government officials, but such a capital drew a large population from all over the empire, its population reaching, according to some estimates, as high as one and a half million.

At first, all these expenditures stimulated trade with Western Europe, which helped both the Arab and Frankish empires. Unfortunately, continued heavy spending by the caliphs on expensive palaces, court ritual, adorning such cities such as Baghdad, and patronizing culture and the arts drained the treasury, which in turn wrecked trade with Europe. With trade so disrupted, Vikings in Russia and the Baltic Sea and Arabs in the Mediterranean turned increasingly to raiding and piracy in the ninth and tenth centuries. This brought the Dark Ages to their lowest point in Western Europe.

The development of Islamic Civilization

The period of roughly 750-1000 C.E. is known as a cultural golden age for Islam. During this period, the vigorous desert tribesman from Arabia assimilated the older cultures of the Near East and Mediterranean and infused new life into them.

The basis for such a golden age was the orderliness and resulting prosperity that Arab rule brought the empire from India to the Atlantic. The Arabs flourished as middlemen in a trade that involved silks and porcelains from China, gems and spices from India, slaves and gold from Africa, and slaves and furs from Europe. The stability and range of this trade are seen by a custom of writing letters of credit that would be honored in other cities of the empire. The Arab word for this, sakk, is the origin for our word "check". The Italian city-states would adopt these practices to become the premier centers of business in Europe in later centuries.

There were three main cultures the Arabs assimilated and fused into what we call Muslim civilization: Indian, Persian, and Greek. From India, the Arabs picked up two concepts essential to the evolution of mathematics: the place value digit and zero. Both of these were vital to being able to do much more complex calculations than the old system of using letters represent numbers.

From the Persians, the Arabs inherited the full scope of Near Eastern cultures that extended back to the early days of Sumer. Much of Muslim art and literature was heavily influenced by Persia. The classic One Thousand and One Arabian Nights, with such tales as Sinbad the Sailor and Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, dates from this period. Poetry also flourished, although it should be noted that the Arabs already had a strong poetic tradition before the conquests. Even such games as Backgammon, Chess, and Polo came to Islamic civilization by way of Persia.

The Greeks also contributed substantially to Muslim culture in the fields of philosophy, math, science, and architecture. Mohammed had said nothing wastes the money of the faithful more than building. However, the Muslims were great builders who owed much of their architectural skill and style to the Greeks. It takes little imagination to see the relationship between the dome of a Moslem mosque and the dome of a Byzantine church such as the Hagia Sophia.

Arab rule and civilization had important results by way of providing economic stability and the spread of civilization. In time, it would pass many of its ideas to India, modern Islamic culture, and even Western Europe where they would be instrumental in the flowering of culture known as the Italian Renaissance.

FC46AThe Origins of the Sunni-Shi'Ite Split

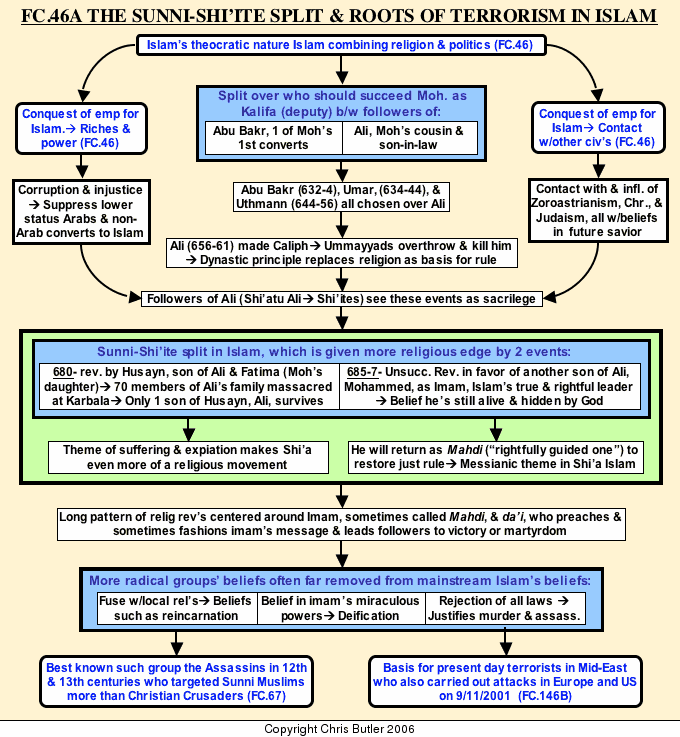

Beginning of the rift. Soon after Mohammed’s death in 632 C.E., the Islamic world suffered a religious/political schism that still constitutes the major divide among Muslims today: the Sunni-Shi’ite split. What made this so serious is the theocratic nature of Islam that combines religion and politics, where religious law, especially the Quran, rules state and society. This affected the Muslim world in three ways.

Two of them had to do with the Muslim Arabs’ mission to spread Islam, resulting in the rapid conquest of a vast empire stretching from India to Spain. This, in turn, had two effects. One was the sudden accumulation of great power and riches by Arab leaders, who in many cases became corrupt and oppressed poorer Arabs and non-Arab converts to Islam. These conquests also brought the Arabs into increasing contact with and influence from Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and Judaism, all religions with belief in a future savior.

Meanwhile, a split had arisen between followers of Abu Bakr, one of Mohammed’s first converts, and Ali, the prophet’s very pious cousin and son-in-law over who should succeed as Kalifa (AKA caliph, literally deputy). Abu Bakr (632-634) was chosen over Ali, followed by the puritanical and severe Umar (634-44). When a Christian slave murdered Umar, Ali was again passed up in favor of Uthman from the powerful Umayyad clan. As was accepted custom, Uthman appointed many of his relatives to high posts in the rapidly expanding empire. When complaints about one of those relatives’ corruption came to him, a dispute broke out which ended in Uthman’s murder by an angry mob. In the aftermath, Ali was chosen caliph. However, Muawiya, the governor of Syria, led Uthman’s Umayyad relatives in revolt. In 661 Ali, last of what were known as the four Orthodox Caliphs, was murdered, and Muawiya founded the Umayyad dynasty (661-750) in his place.

However, the dispute was far from over, because many Muslims believed Mohammed had designated that only his son-in-law, Ali, and his descendants should rule as imam (he who walks in front or guides). This, combined with growing discontent over Umayyad corruption and oppression, became the basis of the Sunni-Shi’ite split. Shi’a is the shortened form for Shi’atu Ali, meaning followers of Ali, while Sunni comes from Ahl as-Sunnah wa’l-Jamā‘ah meaning "people of the example (of Muhammad) and the community".

Two events in the decades after Ali’s death intensified the dispute. In 680 C.E., a revolt by Ali’s son, Husayn, was put down when he and seventy other members of his family were massacred in the present-day Iraqi city, Karbala, making this the Shi’ites’ holiest city after Mecca and Medina. Only one son of Husayn, Ali, survived this massacre. Five years later, Ali’s oldest son, Hasan, failed in an attempted revolt against the Umayyads. Twelvers, the dominant branch of Shi’a Islam, believe that Ali, his two sons, Hasan and Husayn, and a succession of nine of Husayn’s descendants are the Twelve Imams. Many Shi’ites believe the twelfth and last of these imams, Muhammed ibn al-Hassan, is still alive and hidden by God until his chosen time, when he will return as the mahdi (rightfully guided one) with Jesus to restore just rule to the earth. Shi’ites believe the imams possess supernatural knowledge directly from God and thus are infallible. Sunnis reject this claim.

The deaths of Husayn and Hasan have also given Shi’a Islam a theme of suffering and expiation. This has justified in many Shi’ites’ minds a long pattern of revolutions centered on the da’l, preachers of the imams’ message who lead their followers to victory or martyrdom. These have given rise to more radical groups, some with beliefs far removed from mainstream Islamic beliefs. At least one group incorporated local beliefs, such as reincarnation, into their own. Others have gone so far as to deify the imams, attributing to them miraculous powers. Some Shi’ites, by rejecting all, especially Sunni, law have justified such things as murder and assassination, which has been the cornerstone of beliefs for a number of terrorist groups. One of these groups, known as the Assassins, targeted Sunni Muslims and crusaders in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, murdering anyone who refused to pay them tribute. Our word, assassin, comes from hashish, which this group’s followers would supposedly smoke before carrying out their political murders.

This is also the basis for present day resistance groups who, rightly or wrongly, are labeled terrorists. For example, Hezbollah (“Party of God”) in Lebanon, which started out as a resistance group without a solid base, has over the years come to provide many of the social services, such as schools and hospitals for many Lebanese Shi’ites. Ironically, the main terrorist group and nemesis of the West since the 1990s, Al Qaeda, is Sunni. Today, Sunnis make up about two-thirds of the Muslim world, but Shi’ites predominate in Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon. Most Shi’ites are known as Twelvers, believing in the twelve imams, but there are various splinter groups, such as the Ismailis and Zaydi (Fivers) who believe in a different line of succession for the imams. Both Shi’ites and Sunnis revere the Quran as the revealed word of God.

FC46BMuslim civilization in Spain (711-1492)

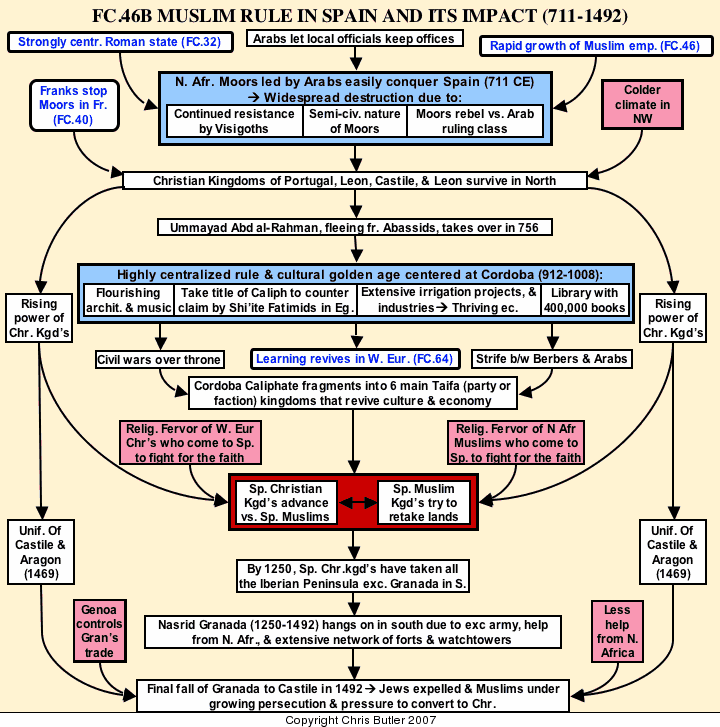

The coming of the Moors

In the seventy years after the death of Mohammed in 632, the Arab Muslims conquered an empire that stretched from the borders of India in the East to the Atlantic coast of North Africa in the West. In 711, an Arab general, Tariq, was sent into Spain with a force of unruly North African Berbers (from the Roman word for barbarians). Tariq, after whom the Rock of Gibraltar was named (from Jebel Tariq, the Rock of Tariq), decisively defeated the Visigoth king Roderic in 712, after which the Moors, as the Arab-led Berbers were called, overran the rest of the peninsula by 720.

Several factors aided the rapid Muslim conquest of Spain. First, despite the hilly and fragmented nature of Spain's geography, the Romans had succeeded in creating a tightly knit and romanized province (both politically and culturally). Rome's Visigothic successors carried on these traditions, thus giving the Moors a fairly unified state whose government largely fell into their hands after one decisive battle, much as England fell to the Normans after the Battle of Hastings in 1066. A very different, but complementary factor was the de-centralized nature of Roman (and Visigothic) rule, where local nobles who copied Roman culture and showed loyalty to the empire, were allowed to run their cities or regions for Rome. There is evidence the Moors avoided prolonged sieges by confirming these local officials in their positions in return for their loyalty. Therefore, there was often little more than a change of management at the top that many people might not have even noticed.

By the same token, the Moorish conquest and its aftermath to c.800 seem to have been a fairly destructive and chaotic period in Spanish history for several reasons. For one thing, there was some resistance by the king and his nobles who lost their lands to Tariq's followers. Secondly, the Berbers who made up the bulk of the conquering army, were still unruly tribesmen and, for the most part, only superficially Muslim. Thus they often plundered and destroyed at will. Finally, although all Muslims were supposedly equal, the Arab rulers and officers treated the Berbers as second class citizens, taking the best lands and lions' share of the plunder for themselves. This triggered a Berber revolt and period of turmoil (c.740-90).

This anarchy allowed the survival of the Christian states in the north, the most prominent of which would evolve into Portugal and Leon in the west, Castile in the middle, and Aragon in the east. Likewise, the Franks, who had turned back the Moors at Tours in 733, entered northern Spain in 778 under Charlemagne, supposedly to help the city of Sargasso. Although this expedition failed, Charlemagne's son, Louis I established a more permanent Frankish presence and military frontier, the Spanish March, in the northeast. This helped knit strong cultural ties with Catalonia, centered around Barcelona, which has maintained its own Catalan culture and language (a mixture of French and Spanish) and still harbors designs for political independence, much like the Basques do in the north-west.

The Ummayad Caliphate of Cordoba (c.800- 1008)

During this time, Abd al-Rahman, the lone survivor of the Ummayad Dynasty in the East after the Abassid Dynasty's bloody coup, had escaped to Spain and gradually extended his control there (756-88). The Ummayads always had trouble maintaining firm control of their frontier regions, which were remote, turbulent, less wealthy and sparsely populated. This forced them to give more freedom and power to their military governors so they could defend the frontiers against the constant raiding that created a virtual no-man's-land between the Christian and Moorish realms.

However, under Abd al-Rahman III (912-61), al-Hakem II (961-76) and the viziers al-Mansur and his son Abd al-Malik ruling for the weak Hisham II (976-1009), the Ummayads established some degree of control over the frontiers and presided over the height of Muslim power in Spain. In 929, they even took the title of Caliph, spiritual and secular ruler of the Islamic world, most likely in reaction to the Shiite Fatimids in North Africa claiming that title by right of descent from Mohammed's daughter, Fatima. The Ummayads also moved their capital from the old Visigothic center, Toledo, to Cordoba, where they built one of the Islamic world's most splendid mosques and a magnificent palace complex. This palace had 140 Roman columns sent from Constantinople, a menagerie, extensive fishponds, and a room with a large shallow bowl of mercury that, upon shaking, reflected light wildly around the room like lightning in order to impress and terrify visitors. The court was also a flourishing center of culture, especially after the renowned Arab musician, Ziryab was attracted there from the East, bringing with him the latest in fashionable foods, clothing, and personal hygiene, most notably toothpaste. Cordoba was famous for its extensive library with 400,000 books and may have had a population of 100,000, making it one of the most splendid cities in the world at the time.

At this time, a growing number of Christians started coming from Northern Europe to absorb the growing body of knowledge stored in Cordoba, taking back such things as the abacus, astrolabe, Arab math and medicine, and translations of Aristotle. This transmission of Arab learning from Spain would be the basis for the revival of learning in Western Europe in the following centuries.

By 950, the population of Moorish Spain was largely Muslim, since as many as one million Berbers may have migrated to Spain and many Spanish Christians converted to Islam, either out of conviction, the influence of friends and family, or the improved opportunities such conversion might bring. Evidence for these conversions comes from the large number of Arab genealogies, which often show a point where Christian names are replaced by Arabic ones, indicating their conversion to Islam. Another source of converts was slaves, largely Slavs brought from Eastern Europe by Viking traders. These were often converted to Islam and trained as slave bureaucrats or bodyguards (although slaves with much higher status than the average subject). The caliphs in Cordoba had as many as 60,000 such recruits in their army, which largely freed them from dependence on unreliable Berber recruits.

Maintaining such a splendid court, capital, and army required a vibrant economy, which seems to have recovered in general across the Mediterranean after 750 and particularly in Spain after the turmoil of the 700s. Spain's agriculture especially flourished, from such new crops as rice, hard wheat for pasta (which required less water and stored better as a result), sorghum, sugar cane, cotton, oranges, lemons, limes, bananas, pomegranates, figs, watermelon, spinach, and artichokes. Figs, which were a Byzantine monopoly, supposedly reached Spain by smuggling seeds wrapped in a book past the customs agents. Making this "green revolution" possible were extensive irrigation and waterwheel systems copied from Syrian models, the largest being around Valencia. There were reportedly 5000 waterwheels along the Guadalquivir River alone by 1200.

Better agriculture produced a healthier and more numerous population, which allowed the government to lower tax rates, which in turn promoted more innovation, thus creating even better agriculture, and so on. This, of course, allowed and encouraged urban growth and more industries, such as metals, ceramics, glass, silk, ivory carving, paper and book making, woolens, and dying with dyes imported from as far away as India. One indication of Moorish Spain's prosperity at this time was government revenue, which reached 6,500,000 gold dinars a year.

Fall of the Caliphate of Cordoba and rise of the Taifa, or "Party kings" (1008-c.1080)

After the death of the powerful vizier, Abd al-Malik, a period of civil wars and strife known as the Fitnah broke out (1008-31). Various claimants to the throne had to rely on Berber mercenaries, who claimed lands and provinces for their services. As a result, a string of caliphs rapidly followed one another, one supposedly reigning for only forty-seven days. In 1013 Cordoba was sacked and its library destroyed by Berber troops who, resenting their inferior status under the Arabs, saw no reason to preserve their culture. While the government disintegrated at the center, Christian princes in the north raided and conquered Muslim lands or extorted tribute from local rulers.

This chaos led to a fragmentation of power into some three dozen city-states known as the Taifa (literally party or factional rulers, although our other meaning for party might also apply). Gradually, the smaller taifas were gobbled up by the larger ones, leaving six main ones: Seville and Granada in the south, Badajoz, Toledo, and Valencia in the middle, and Zaragoza in the northeast. Once affairs settled down and stabilized, there was a rapid revival of the economy and culture. However, rather than being concentrated at one central court, culture was dispersed and localized in a number of taifa states. Taifa rulers' status, much like that of princes in Renaissance Italy, rested as much on which scholars and artists they could attract to their courts as it did on warfare and conquest.

The richest of the taifa states was Seville in the lower valley of the Guadalquivir River, specializing in its olive oil, crimson dye made from a beetle, sugarcane, and musical instruments. Its rulers, al-Mu'tadid (1042-69) and his grandson, al-Mu'tamid, took Seville to the height of its cultural prestige and political power (even recapturing Cordoba from the Christians in 1069), and were themselves accomplished poets.

Meanwhile, the Christian states of Aragon-Catalonia in the east, Castile-Leon in the middle, and Portugal in the west were attacking and extorting tribute from the various taifa states. Such tribute was a major, if not the main, source of revenue for these princes who, in turn, passed it on to their soldiers, nobles, churchmen, and merchants, making it a vital part of their economies. Joining in this were Muslim and Christian mercenaries who would fight for either side, depending on the pay and circumstances. The most famous of these was Rodrigo Diaz, known as El Cid (from the Arabic word for boss). During his very active career, Diaz served Castile (until he was exiled from there), the Muslim ruler of Zaragoza (fighting both Christians and Muslims), and Castile again until another falling out with its ruler. Having built up his own fortune, reputation and following, he fought, plundered, and extorted tribute from both Christians and Muslims until he took Valencia in 1094, where he ruled until his death in 1099.

Islamic resurgence from North Africa: the Amoravids & Almohads (1080-1250)

Just as the Moors had originally come from North Africa and constantly drawn upon its Berber tribesmen for settlers and soldiers, so they drew renewed strength from two more North African groups to stem the tide of Christian conquest. The first of these, the Almoravids, were led by ibn Yasin, who had founded a ribat, a frontier religious community with a strong military character since it must be able to defend itself, and spread Islam through preaching and charity. As ibn Yasin's movement grew, it came to be called the Almoravids (from al-Murabitun, meaning people of the ribat). They founded Marrakech as a base in 1060 and took over Morocco by 1083.

They then turned toward the taifas in Spain which they saw paying tribute to non-Muslims, not recognizing the authority of the caliph in Baghdad, and failing to abide by the Muslim ban on drinking wine. In 1085 when the ruler of Castile took over Toledo, several alarmed taifas called the Almoravids into Spain for help. In 1086, the Almoravids crushed Castile's forces and embarked on a series of campaigns (c.1100-1125) to recover lands recently lost to the Christians. If the Almoravids were intolerant of any breaches of Islamic law by fellow Muslims, they were even less tolerant of Jews and Christians. From this point on we see growing hostility between Christians and Muslims who used to tolerate each other. Add to this aggressive Christian princes desperate to recover the lost revenue from tributes cut off by the Almoravids and a Church reform movement that wanted to channel the military energies of Europe's nobility into campaigns, such as the wars in Spain and the Crusades, to serve its own interests, and one can see a growing strain of intolerance that would plague Spain for centuries.

Arrogance toward other Muslims, growing indulgence in the very luxuries they had originally condemned, and the re-emergence of Berber tribal loyalties led to Almoravide decline after 1125. However, a new group of North African reformers emerged to take their place, the Almohads (from al-Muwahhidun, upholders of divine unity). Founded by Muhammed ibn Tumart, their career seemed to parallel that of the Almoravids, starting with a ribat and winning over the local tribes with their own brand of religious fervor. One major difference between the two movements was that the Almohads believed in a more mystical unity of God in which all of us are immersed. In 1121, ibn Tumart was declared the Mahdi (rightly guided one) by his followers to restore righteousness in the final days before the Last Judgment. At this time, the Christian princes were taking advantage of a new period of turmoil (sometimes referred to as The Second Fitnah) by conquering more lands. In 1146, Alfonso VII of Castile briefly took Cordoba before losing it again. The following year, Alfonso I of Portugal took Lisbon with the help of an English navy, marking the start of a long friendship between those two countries. Consequently, a Sufi leader, ibn Qasi, called in the Almohads who took over the Almoravids and attacked the Christian states, inflicting a crushing defeat on them at Alcaros in 1195. This served as a wakeup call to the Christian states, which united against the Almohads and stopped them decisively at Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212.

In the ensuing forty years (1212-52) nearly all the Iberian Peninsula came under the three Christian states of Portugal, Aragon, and Castile. Fernando III of Castile took Cordoba in 1236, and Seville fell to him in 1248 after a grueling siege. In the latter case, he ejected the surviving population and replaced it with Christians. A later elegy on the fall of Seville by the poet ar-Rundi seemed to bemoan the fate of Muslim Spain in general:

Ask Valencia what became of Murcia,

And where is Jativa, or where is Jaen?

Where is Cordoba, the seat of great learning,

And how many scholars of high repute remain there?

And where is Seville, the home of mirthful gatherings

On its great river, cooling and brimful with water?

These cities were the pillars of the country:

Can a building remain when the pillars are missing?

The white wells of ablution are weeping with sorrow,

As a lover does when torn from his beloved:

They weep over the remains of dwellings devoid of Muslims,

Despoiled of Islam, now peopled by infidels!

Those mosques have now been changed into churches,

Where the bells are ringing and crosses are standing.

Even the mihrabs weep, though made of cold stone,

Even the minbars sing dirges, though made of wood!

Oh heedless one, this is fate's warning to you:

If you slumber, Fate always stays awake.

Nasrid Granada and the end of Moorish power in Spain (c.1250-1492)

By the mid thirteenth century, Moorish power in Spain was confined to a thin mountainous strip of land in the south that was never more than sixty miles wide. In the 1230s and 1240s, Muhammed ibn Yusuf ibn Nasr established a state centered around the city of Granada, thus giving his name to its ruling dynasty (Nasrid). Granada's strength was undercut by two main factors. First of all, it suffered from a good deal of internal disunity caused by tribal divisions, the ever-troublesome Berber mercenaries from North Africa, and an influx of Muslim refugees from the north. Second, it had a weak economy caused by its poor soil, forcing it to import much of its food, while its trade was largely controlled by Genoese merchants. Also, heavy tribute to the Christian states in the north forced the amirs (rulers) of Granada to charge high taxes, which made them unpopular.

Granada's survival depended on several factors: an excellent army consisting largely of Berber light cavalry, an extensive system of castles every five or six miles along its frontier and as many as 14,000 watchtowers scattered across the countryside, strong support from the Merinid dynasty in North Africa, generally capable rulers until the early 1400s, and some luck, such as the intervention of the Black Death (1349), Castilian involvement in the Hundred Years War in the 1300s, and turmoil both within and between the various Christian states.

Despite its problems, culture flourished in Nasrid Granada, especially in the fields of poetry, architecture, and art. The most remarkable example of this is the Alhambra, probably the best surviving example of a medieval Muslim palace. Much of its beauty lies in its elegant gardens, fountains, and courtyards that provided a serene setting for meditation, reading, or romance. The rooms of the palace itself show Islamic decorative art at its peak, with intricate geometric designs gracing the walls, doorways, and ceilings. According to the poet, Ibn Zamrak:

“...The Sabika hill sits like a garland on Granada's brow,

In which the stars would be entwined,

And the Alhambra (God preserve it)

Is the ruby set above that garland.

Granada is a bride whose headdress is the Sabika, and whose adornments are its flowers.”

In the 1400s, Granada's luck ran out in several ways. Genoese control of its trade tightened, which further aggravated resentment caused by the high tax rates (three times that paid by the people in Castile) to pay tribute to the Christians. The Merinids in North Africa went into decline and could no longer provide Granada their support. Tribal strife within Granada increased while the Christian states of Portugal, Castile, and Aragon resolved their own internal problems. In 1469, Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile married, thus uniting Spain into one powerful state when they ascended their respective thrones in 1474. The only missing piece of the puzzle, in their minds, was Granada, which they attacked in 1482. The war boiled down to a series of sieges, as one city after another fell to the Christian artillery. In 1492, after an eight-month siege, Granada fell to Ferdinand and Isabella, who accepted the surrender dressed in Moorish clothes. After nearly 800 years, Spain was again united under Christian rule.

For Spain's Jewish and Moorish subjects, Christian rule was anything but pleasant. Almost immediately, the Jews were expelled from Spain, thus depriving it of some of its most productive population. Despite Ferdinand and Isabella's promise to tolerate their religion, the Muslims were forced to convert to Christianity or leave Spain in 1502. Since emigration was so costly, most converted in name while secretly maintaining their own beliefs and practices. In 1568, Philip II, increasingly concerned about his image as a strict Catholic monarch and support the Moriscoes (Moors supposedly converted to Christianity) might give to the Ottoman Turks and his other Muslim enemies, tried to stamp out their Muslim customs, which triggered a revolt. After brutally suppressing this uprising Philip dispersed the Moriscoes across Spain. However, since they still refused to assimilate into Christian society, Philip III took the final step of expelling some 300,000 Moriscoes from Spain in 1609. Aside from the suffering it caused the Moriscoes, this also substantially hurt Spain, by ridding it of much of its most productive population just when its power and wealth in other quarters were going into decline. This only accelerated Spain's decline into the rank of a second rate power by the mid 1600s.

Moorish Spain's legacy

As discussed previously, many Christian scholars during the Middle Ages came to Spain to absorb its learning, helping trigger a revival of learning in Europe. Very simply, this was the single most important legacy of Moorish Spain to Europe. One of its most significant contributions came from the philosopher, ibn Rushd (known in Europe as Averroes), who devoted his life to reconciling faith and reason (in particular that of Aristotle). The Christian philosopher, Thomas Aquinas, whose book, Summa Theologica, similarly reconciled faith and reason, quoted ibn Rushd no less than 503 times in his works. It was Aquinas' work that laid the foundations for the Renaissance and the birth of Western science in the centuries to come, but in a very real sense, it was the work of an Arab scholar, ibn Rushd, that was the real foundation.

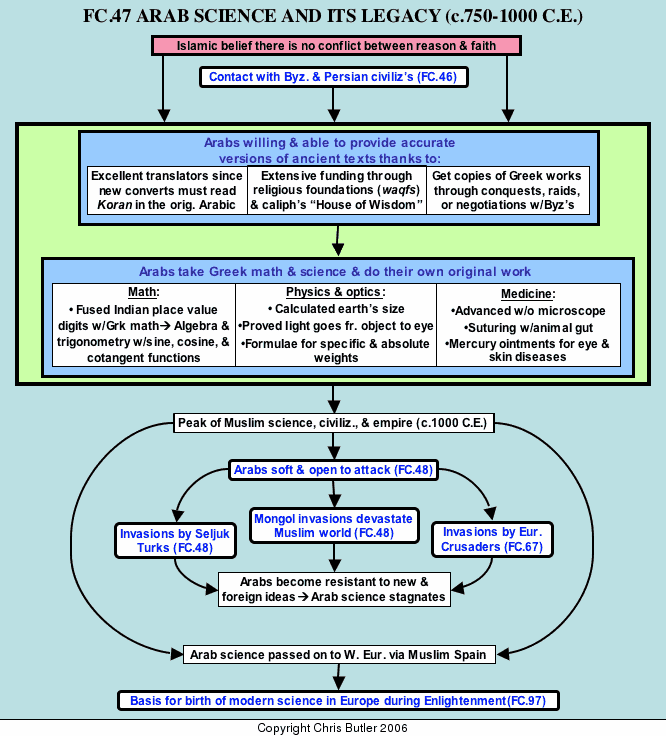

"/>FC47Arab math and science to c.1000

The flow of history sometimes takes some devious twists and turns in its course of events. Such is the case with our own modern science, which received its legacy of Greek science and math not directly from the Greeks, but by way of Islam. Indeed, one of Islam's greatest cultural legacies was the preservation of Greek philosophy, math, and science. Islam and the rise of the Arab empire affected Arab math and science in two ways. First of all, rather than rejecting ancient Greek learning, Muslim culture remained quite open to it. The story goes that the caliph al-Ma'mun had a dream where the Greek philosopher Aristotle assured him that there was no conflict between reason and faith. This revelation led al-Ma'mun to start gathering the works of the Greek philosophers. Second, the rise of their empire directly exposed the Arabs to Byzantine and Persian cultures that still carried on ancient scholarship. Therefore, the Arabs were both willing and able to absorb Greek math and science.

There were three things the Arabs needed to do: get copies of the Greek texts, translate them, and provide funding for these endeavors. As far as getting the books was concerned, many of them had fallen into Arab hands through conquest. However, there were still many texts that they needed. Sometimes they would negotiate with the Byzantines for copies of these books. At other times, raids into Byzantine territory would actually be aimed at seizing such works along with more material plunder.

Once these works had been gathered, the Arabs needed to translate them into Arabic. Luckily, Islam attracted a large number of converts, among them many men educated in Greek. However, since the Koran at that time was written only in Arabic, new converts had to learn that tongue in order to read Islam's holy book. As a result, Islam's appeal created a number of brilliant translators.

Funding largely came from the caliphs themselves. Caliph Ma'mun founded a palace learning center known as the House of Wisdom where many of the most brilliant minds of the age were gathered to translate Greek works and then add to this knowledge. The budget for the House of Wisdom was 500 gold dinars a month, with fifty-seven translators working there at one point. The translator, Hunayn, was supposedly paid the weight of his translated books in gold.

All this led to a level of scholarship that was unsurpassed in its day. Since books were hand written, and thus prone to a growing number of mistakes as each generation of books was copied, the translators would gather as many copies of a particular book as they could. They would then compare these texts to see which was probably closest version to the original text. Just compiling such critical texts alone was one of Islam's greatest legacies to us.

Starting with this excellent base of Greek knowledge, the Arabs made their own advances in the fields of Mathematics, medicine, and physics. Since Islam also encompassed part of India, its math was assimilated into the larger body of mathematical knowledge and passed on to us. The Indians came up with two very valuable concepts that simplify math for us immensely: place value digits and zero. As brilliant as Greek math was, it did not have these two tools, thus severely limiting what it could accomplish, since any math using Roman numerals is extremely cumbersome. Because of such limits, Greek math excelled in geometry, which could function better than other branches of math without place value digits and zero. Even proofs in non-geometric math were done with the brilliant use of geometric figures to illustrate problems.

The Muslims embraced Greek geometry wholeheartedly. One need only look at Islamic art and architecture to see their fascination with various geometric shapes and the ingenious things they could do with them. The religious ban on portraying the human figure certainly spurred Muslim art to excel in this direction.

However, the Muslims did not just slavishly copy the Greeks. Rather, they made their own original contributions in the fields of mathematics, medicine, and physics. Equipped with the Indian place value digits and zero, they developed trigonometry and first clearly defined sine, cosine, and cotangent functions. They further developed algebra (from the Arabic, al-jabr, which means "the missing"). The mathematician al-Khwarizmi wrote the first textbook on algebra and was probably the first to solve quadratic equations with two variables. In future centuries his textbook would be the basis for European algebra. It has been said that science is always pushing against the frontiers of math. If that is true, then the Muslim mathematicians certainly allowed those frontiers to be expanded considerably.

As advanced as Islamic math and science were for their day, we should keep in mind that scientists then were not specialized in the way scientists today are. For example, the translator Qusta ibn Luqa wrote on such topics as politics, medicine, insomnia, paralysis, fans, causes of the wind, logic, dyes, nutrition, geometry, astronomy, etc.

The Arabs also excelled in medicine. The great physician al-Rhazi, or, as he was known in Europe, Rhazes (865-923), correctly differentiated between the symptoms of small pox and measles and showed that diagnosis on the basis of examining a patient's urine was not very useful. He also used animal gut for suturing wounds and developed mercurial ointments for treating skin and eye diseases. Keep in mind that the accomplishments of Muslim science were done without the microscope. Not until that was invented in the 1600's would scientists be able to see microbes and understand the real causes of most diseases. This makes Muslim medicine seem all the more remarkable.

Al-Rhazi also knew how to use psychological treatment. It is said that he was once commissioned to cure a caliph stricken with paralysis. He took the caliph to a cave and threatened him with a knife. The enraged caliph got up and chased al-Rhazi out of the cave and into exile. Al-Rhazi later sent a letter explaining that was the treatment, and the caliph subsequently rewarded the physician.

Muslim scientists also made advances in physics and optics, anticipating later European theories on specific gravity and developing formulae for figuring specific and absolute weights of objects. They calculated the size of the earth to an unprecedented degree of accuracy, though they still followed Aristotle in their belief in the geocentric (earth centered) universe. Muslim scientists disproved the Greek theory that light emanates from the eye to the object perceived. Ibn al-Hathan showed this theory was wrong by studying how light is refracted through water.

Muslim civilization peaked around 1000 C.E. But, as with other civilizations, a higher level of culture tended to make the Arabs soft and open to attack. Also, Arab civilization was also running into problems of internal decay that triggered two waves of invasions. First came the Seljuk Turks out of Central Asia. Although they did adopt Islam & restore some of its unity, the arrival of these Asiatic nomads initially had a somewhat disruptive effect on Arab culture and its attitudes toward the outside world. Even more upsetting in this respect were the Crusades, wars of conquest waged by Christians from Western Europe to recover Palestine for their faith. Unlike the Turks, the Crusaders were not about to convert to Islam and were much more hostile toward and destructive of Arab civilization, especially in the early years of the crusading era. Finally, the most destructive invasions of all came from the Mongol onslaught in the 1200's. The wholesale massacres of populations and destruction of cities that they committed dealt a terrible blow to Islamic civilization. These invasions were such a shock to the Arabs that Muslim culture became much more resistant to new ideas and foreign influences, making it more conservative and inward looking.

This helped cause a religious reaction against putting too much emphasis on science and reason and too little emphasis on faith. Except for the House of Wisdom, science and learning were largely supported by religious institutions and thus subject to their conservative influences. Also there arose a mystical movement known as Sufism, which discredited learning and reason, believing in a more direct and mystical experience with God. From this point on, Muslim science and math started to stagnate.

However, Islamic science spread to Western Europe and survived. By the 1100's, translations of Arabic texts were making their way from Muslim Spain into European universities. These Arab texts stimulated the growth of Western science, which is the dominant scientific tradition today. We should never lose sight of the fact that our own science today rests squarely on the accomplishments of Muslim science, which, as a result, is still very much alive.

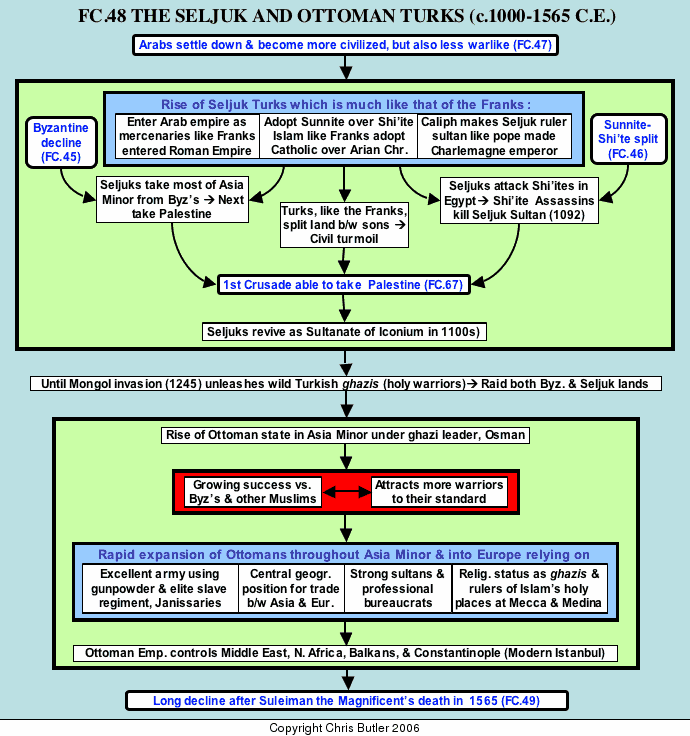

FC48The rise of the Seljuk & Ottoman Turks (c.1000-1565)

The Seljuk Turks

Although Islam experienced a golden age under the Abbasids, the empire gradually fell apart as the Arabs became less warlike and one province after another broke away. Weak caliphs under the power of mameluke bodyguards, the size of the empire, and the disaffection of Shiites and various ethnic groups all led to this disintegration. Fortunately for Islam, a new people came in to revitalize it: the Seljuk Turks.

Various Turkish tribes had been known for centuries from the borders of China to the borders of Islam. Fortunately, the Persians and the Arabs had held them in check. Instead of overwhelming the empire, these Turkish tribesmen, infiltrated it, coming in as mamelukes and mercenaries whom the Arabs relied on more and more, much as the Romans had relied on Germanic troops. An even more interesting parallel is between the most successful Germanic tribe in Europe, the Franks, and the most successful Turkish tribe in Islam, the Seljuks.

The Seljuk Turks, named after a semi-legendary leader and founder, were the first Turkish tribe to convert to Sunnite Islam, thus gaining the favor of the civilized population in much the same way as the Franks' conversion to Catholic Christianity had made them more popular with their subjects. The Seljuks also came to the aid of Islam's spiritual leader, the caliph, who was under the thumb of a Shiite dynasty known as the Buwayids, much like the Franks under Pepin and Charlemagne had protected the Pope from similar difficulties. And in each case, the spiritual leader granted his protectors the title and responsibility for defending the faith. In the case of the Seljuks, their leader Toghril was made king, or sultan, of the East and West in 1058 with the job of restoring the political and religious unity of Islam.

Because of their dual mission to unify Islam and expand its frontiers, the Seljuks turned against the Shiite dynasty of the Fatimids in Egypt and Palestine and also against the Christian Byzantine Empire (much as Charlemagne had waged campaigns for Christianity in Spain and Saxony). One reason for these wars was to divert the ever-growing number of wild Turkish tribesmen away from destroying fellow Muslims and towards waging the holy war outside its borders. Because of their ongoing decline, the Byzantines were the ideal target, although the Shiite Fatimid dynasty in Egypt was also a useful target. In each case Seljuk victories triggered a backlash.

In 1071, the Seljuks and Byzantines met in the Battle of Manzikert. The result was a resounding victory for the Seljuks who then proceeded to take over most of the Byzantine heartland in Asia Minor. Their military, political, and religious victory was so complete there that we still call that land Turkey, even though it is a long way from the Turks' original homeland in Central Asia. The Byzantine emperor, Alexius I, called for mercenaries from Western Europe to help him reclaim Asia Minor from the Turks. Instead, he got the First Crusade, which took much of Syria, and Palestine for the Christian faith.

At the same time, the Seljuks were expanding against the Shiite Fatimids, which brought them up against a fanatical Shiite sect known as the Assassins. This group was centered in a mountain fortress and led by Hassan-ibn-al-Sabah, also known as the Old Man of the Mountain. Determined to stop the advance of the Sunnite Seljuks, he launched a campaign of political terror and murder that has become legendary. Hassan's followers operated under the influence of the drug, hashish, from which we get the word assassin. They showed remarkable determination and ability to infiltrate the most tightly guarded palaces and reach their intended victims with their poison daggers. Among those victims was the Seljuk sultan, Malik Shah, in 1092. His death combined with the First Crusade and the Seljuk custom of dividing their realm between all their sons (much as the Franks had done), created enough turmoil in the Seljuk realm to allow the Crusaders to take Palestine. Despite these setbacks, the Seljuks did manage to restore their power in Asia Minor. Their state, the Sultanate of Rum (Rome), thrived throughout the 1100's. However, much like the Franks with the Vikings, The Seljuks had their own nemesis: the Mongols.

In the early 1200's, a leader known to us as Genghis Khan united the various Mongol tribes in Central Asia into the most fearsome war machine known to history up to that point. Striking at incredible speed (up to 100 miles a day), they burned a path of destruction from China to Europe and the Muslim world unsurpassed until the wars of the twentieth century. Cities daring to resist them were methodically destroyed and their populations put to the sword. The defiance of the Assassins brought the wrath of the Mongols upon the Muslim world. In 1245, the Mongols annihilated the Seljuk army at Kose Dagh. In 1258, they sacked Baghdad and killed the last in the line of Abbasid caliphs. The Egyptian sultan Baibars finally halted the Mongols’ relentless advance in 1260. The Mongols eventually settled down and even adopted Islam in the Muslim areas where they ruled. However their rampage had far reaching effects on the Turks and the Islamic world.

Rise of the Ottoman Turks

On the frontier between the Turks and the Byzantines were various warlike groups, know as ghazis (holy warriors) for their efforts against the Christians. While the Sultanate of Rum was intact, these bands were largely held in check, since their wild ways were often as disruptive to the Seljuks as to the Byzantines. With the shattering defeat at Kose Dagh, however, these ghazi bands were freed to raid at will. Among them was a leader of particular renown, Osman, who gave his name to the greatest of the Turkish states, the Ottomans.

Osman's leadership in battle attracted many Turkish warriors to his standard and made him the most successful of the ghazi states attacking the Byzantines and neighboring Muslims. His successes brought conquests and plunder which attracted more ghazis to his standard. This would trigger more campaigns against the Ottomans' enemies, which would bring more conquests and so on.

There were various reasons for the Ottomans' success. First of all, their army was the best in Europe and the Middle East. In addition to swarms of tough Turkish cavalry, the sultans also had the age's best artillery and its most dreaded regiment: the Janissaries. These were originally young boys taken from the homes of the sultan's Christian subjects and raised in his service as devout Muslims. Technically, the Janissaries were the sultan's slaves, but slaves with very high status. Trained to a peak of high efficiency, they ruled the battlefields from Persia to Eastern Europe.

Ottoman government was also well organized. Much of the bureaucracy was a class called ghulams, also originally Christian boys taken from their homes by the sultan's men. Like their counterparts in the army, the Janissaries, they were also known for their loyalty and efficiency. At the top of the government was the sultan, who had received "on the job" training as a boy, ruling provinces with the aid of experienced ministers. Upon the death of a sultan, his sons would typically fight for the throne. Such struggles were usually to the death, but, along with the training of the sultan's sons, did tend to produce the toughest and ablest rulers.

The Ottoman sultans also emphasized their religious position to claim leadership of Islam. For one thing, they were ghazis fighting for the faith. Later, they also controlled the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, as well as the last shadowy claimants to the Abbasid caliphate.

However, for a number of years, the Ottomans were seen as just one of a number of ghazis. Then, in 1345, they took the opportunity to intervene in a Byzantine civil war in Europe. And once they had crossed into Europe, they were there to stay.

By 1400, the Ottomans had subdued the other ghazis in Asia Minor and were poised to take that long sought prize of the faithful, Constantinople. Then disaster struck when the last major eruption of nomadic tribes from Central Asia burst upon the scene. Their leader was Timur the Lame, whose path of conquest and destruction ranged from India to Russia. In 1402, he destroyed the Ottoman army, captured the sultan, Bayezid, and dragged him around in a cage for the rest of his days as a monument to his triumphs.

Timur's intentions were to loot and plunder, not to build a lasting state. As a result, his empire disintegrated upon his death, and the Ottomans were able to reassert their control in Asia Minor and Europe. By 1453, they were at the walls of Constantinople, finally ready to claim that prize.

The siege of Constantinople was the last heroic stand of the Byzantine Empire in one of the most desperate and hard fought struggles in history. It saw the destructive power of the newly emerging gunpowder technology being used alongside old style siege towers, galleys, and crossbows. In the end, the defenders were overwhelmed, and the Byzantine (and Roman) Empire passed into history.

For Europe, the fall of Constantinople meant that the old trade routes to the Far East were shut off by the Turks and new ones had to be found. This helped spur Portuguese exploration around Africa and Columbus' famous voyage to America. The fall of Constantinople also caused a number of Greek scholars to flee to Italy where they helped to stimulate the Italian Renaissance, one of the great cultural periods in history. In that way the Byzantines still lived on. For Islam, the victory meant that the Ottoman Turks had arrived as a major power. For the next century and a half, their very name would terrorize the Christian world.

The century from the fall of Constantinople in 1453 to the death of Suleiman the Magnificent in 1566 saw the Ottoman juggernaut roll to an almost unbroken series of conquests against both Christians and neighboring Muslim states. Mohammed II (1451-1481), the conqueror of Constantinople, continued his path of conquest, bringing the Balkan Peninsula south of the Danube River under his control.

The sultan Selim I (1512-1520), known to history as "the Grim", concentrated on his Muslim neighbors. To the east was a revived Persia under the Shiite dynasty of the Safavids. In 1514, Turks and Persians met on the field of Chaldiran. Turkish superiority in artillery and firearms proved decisive as the Persian cavalry were swept away by the Ottomans' massed gunfire. However, the Persians, learning from this, changed their strategy, laying waste the land before the Ottoman advance so the invaders would have nothing to sustain them. This proved effective, and a stable, if uneasy, frontier emerged between the Persian and Turkish realms.

Selim was more successful against the Mameluke dynasty centered in Egypt. At the battle of Dabik (1516), the Ottomans once again used their firepower with terrible effect and, this time, with more lasting results. The unpopular Mameluke rule quickly collapsed and Ottoman rule extended into Palestine, Egypt, and Arabia, thus giving the sultan control of Islam's holiest places.

The reign of Suleiman the Magnificent (1520-66) was the high point of Ottoman expansion. His energies were directed mainly in the holy war against the Christians, driving northwest into Europe and due west across the Mediterranean. In 1526, at the battle of Mohacs, Turkish firepower proved its superiority once again, this time against the Hungarians, who left their king and most of their nobility dead on the field. The road to Vienna lay open, and it was here that the Ottoman advance into Europe ground to a halt. The siege of Vienna was the Turks' first major defeat. In its wake, a new frontier emerged between Christian and Muslim worlds, guarded by a complex and expensive series of fortresses on each side.

The Ottoman drive across the Mediterranean also was eventually stopped in two desperate clashes between Turks and Christians. The first was a titanic siege of the Knights of St. John on the strategic island of Malta in 1566. After four months of bitter fighting, a Christian relief force drove the battered Turkish army away. An equally desperate battle was fought at sea at Lepanto in 1571. The fact that there was no place for soldiers to retreat in a sea battle made the hand to hand fighting especially ferocious. After this, the Ottomans' fleet was severely crippled, their tide of victories and conquests pretty much ceased, and their empire entered a long period of steady decline.

FC49The decline of the Ottoman Empire (1565-1918)

In the late 1500's, the Ottoman Empire started going into decline as a result of both internal and external factors. Internally, the Ottomans suffered from three major problems. First of all, after Suleiman's death, the sultans were less capable and energetic, being raised and spending their time increasingly at court with all its harem intrigues. Without the sultan's strong hand at the helm, corruption became a major problem. Second, the Janissaries became a virtual hereditary caste, demanding increasingly more pay while they also grew soft and lazy. Finally, the size of the empire created problems. The sultan was expected to lead the army, setting out with it each spring from the capital. This meant that as the frontiers expanded, it took the army longer to reach the enemy, thus shortening the campaign season to the point where it was very hard to conquer new lands. This especially hurt the Turks at the siege of Vienna in 1529. They did not reach the city until September, and winter set in early with disastrous results for the troops not used to European winters. Because of these factors, the Turks made few new conquests after 1565 and, as a result, gained no significant new revenues and plunder.

Two external economic factors also hurt the Ottomans, both of them stemming from the Age of Exploration then taking place. For one thing, the Portuguese circumnavigation around Africa to India had opened a new spice route to Asia. Therefore, the Turks lost their monopoly on the spice trade going to Europe, which cost them a good deal of much needed money. The other problem came from the Spanish Empire in the Americas that was bringing a huge influx of gold and silver to Europe. This triggered rampant inflation during the 1500’s, which worked its way eastward into the Ottoman Empire. This inflation, combined with the other factors hurting the empire's revenues, led to serious economic decline.

That economic decline hurt the empire militarily in two ways that fed back into further economic decline. First of all, after 1600, the Turks lost their technological and military edge. While European armies were constantly upgrading their artillery and firearms, the Ottomans let theirs stagnate, thus putting them at a disadvantage against their enemies. Also, as Turkish conquests ground to a halt, a stable frontier guarded by expensive fortresses evolved, which drained the empire of even more money. At the same time, Europeans were reviving the Roman concept of strict drill and discipline to create much more efficient and reliable armies. However, the Turks failed to adapt these techniques and, as a result, found themselves increasingly at a disadvantage when fighting against European armies.

Second, the tough feudal Turkish cavalry that had been the backbone of the army in the mobile wars of conquest were less useful to the sultans who now needed professional garrisons to run the frontier forts. Without wars of conquest to occupy and enrich them, they became restless and troublesome to the central government. That combined with the problems from the Janissaries, caused revolts that further disrupted the empire. (Eventually, the Janissaries would become so troublesome that one sultan would have to surround and massacre them.) Both of these military problems, the failure to keep up with the West and the increasingly rebellious army, fed back into the empire's economic decline, which further aggravated its military problems.

The following centuries saw the Ottoman Empire suffer from steady political and economic decay. By the 1800's, its decrepit condition would earn it the uncomplimentary title of "The Sick Man of Europe". Finally, the shock of World War I would destroy the Ottoman Empire once and for all, breaking it into what have become such Middle Eastern nations as Turkey, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Lebanon, and Israel.