The Ancient GreeksUnit 3: The Ancient Greeks

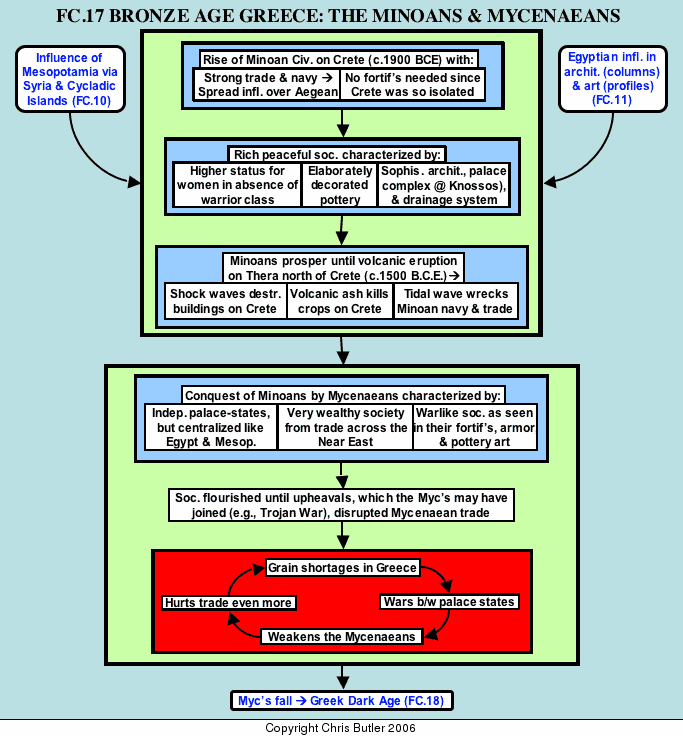

FC17Bronze Age Greece: the Minoans & Mycenaeans (c.2500-1100 BCE)

Introduction

While the peoples of the ancient Near East gave us civilization, the Greeks gave it forms and meanings that make us look to them as the founders of our own culture, Western Civilization. Greek genius and energy extended in numerous directions. Much of our math and science plus the idea of scientific research and the acquisition of knowledge apart from any religious or political authority goes back to the Greeks. The philosophy of such Greeks as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle laid the foundations for the way we look at the world today. Our art, architecture, drama, literature, and poetry are all firmly based on Greek models. And possibly most important, our ideas of democracy, the value of the individual in society, and toleration of dissent and open criticism as a means of improving society were all products of the Greek genius. Even those critical of our own society and Western Civilization overall have the Greeks, creators of Western Civilization, to thank for that right.

Greece's geography strongly affected its history. Greece was a hilly and mountainous land, breaking it up into literally hundreds of independent city-states. These city-states spent much of their time fighting one another rather than uniting in a common cause. Greece was also by the sea with many natural harbors. This and the fact that it had poor soil and few natural resources forced the Greeks to be traders and sailors, following in the footsteps of the Phoenicians and eventually surpassing them.

The Minoans (c.2000-1500 B.C.E.)

The first Greek civilization was that of the Minoans on the island of Crete just south of Greece. Quite clearly, the Minoans were heavily influenced by two older Near Eastern civilizations, Mesopotamia and Egypt, by way of the Cycladic Islands, which formed natural stepping stones for the spread of people from Greece and of civilized ideas from the Middle East. Egyptian influence on the Minoans is especially apparent. Minoan architecture used columns much as Egyptian architecture did. Minoan art also seems to copy Egyptian art by only showing people in profile, never frontally. Still, the Minoans added their own touches, making their figures much more natural looking than the still figures we find in Egyptian art.

Since we have not been able to translate the few examples of their hieroglyphic script, known as Linear A, there are some very large gaps in the picture we have of these people. We do not even know what the people on Crete called themselves. The term Minoans comes from Greek myths concerning a legendary king of Crete, Minos, who supposedly ruled a vast sea empire. As with most myths, there is a grain of truth in this myth, for the Minoans were a seafaring people who depended on their navy and trade for power and prosperity.

Two things, both relating to Crete's maritime position, largely determined the nature of the Minoan's civilization. First, they had a large fleet, which was useful for both trade and defense. Second, Crete's isolated position meant there was no major threat to its security at this time and therefore little need for fortifications. These two factors helped create a peaceful and prosperous civilization reflected in three aspects of Minoan culture: its cities and architecture, the status of its women, and its art, especially its pottery.

The Minoans had several main cities centered around palace complexes which collected the island's surplus wealth as taxes and redistributed it to support the various activities that distinguish a civilization: arts, crafts, trade, and government. The largest of these centers was at Knossos, whose palace complex was so big and confusing to visitors, that it has come down to us in Greek myth as the Labyrinth, or maze, home of the legendary beast, the Minotaur. The sophistication of the Minoans is also shown by the fact that they had water pipes, sewers, and even toilets with pipes leading to outside drains. Since their island position eliminated the need for fortifications, Minoan cities were less crowded and more spread out than cities in other civilizations.

Minoan women seem to have had much higher status than their counterparts in many other ancient civilizations. One likely reason was that, in the absence of a powerful warrior class and a constant need for defense, they had more opportunity for attaining some social stature. This is reflected in their religion where the primary deity was an earth goddess. Minoan art also depicts women as being much freer, even participating with men in a dangerous gymnastic ritual of vaulting themselves over a charging bull.

Minoan art especially its pottery, also shows a peaceful prosperous society, depicting floral designs and such marine wildlife as dolphins and octopuses rather than scenes of war. Its diffusion around the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean shows that Minoan influence was quite widespread, extending throughout the Cycladic Islands and Southern Greece. The myth of Theseus and the Minotaur where Athens had to send a yearly sacrifice of its children to Crete, reflects Minoan rule and indicates that it might not always have been so peaceful. Recent archaeological evidence indicates the Minoans did at times practice human sacrifices.

Minoan civilization continued to prosper until it came to a sudden and mysterious end. A combination of archaeology and mythology provide clues to how this may have happened. The central event was a massive volcanic eruption that partially sank the island of Thera some eighty miles northeast of Crete and left a crater four times the size of that created by the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883, the largest recorded volcanic eruption in recorded history, This eruption had three devastating effects: a shock wave which levelled Crete's cities, a tidal wave which destroyed its navy, and massive fallout of volcanic ash which poisoned its crops. Together these weakened the Minoans enough to let another people, the Mycenaean Greeks eventually take over around 1450 B.C.E.

This seems to correspond to the myth of the lost continent of Atlantis, passed on to the Greeks from the Egyptians who had been frequent trading partners with the Minoans. When the Minoans, whose fleet was destroyed by the tidal wave, suddenly stopped coming to visit Egypt, stories drifted southward about an island blown into the sea (i.e., Thera) which the Egyptians assumed was Crete. Over the centuries the stories kept growing until Crete became the vast mythical continent and empire of Atlantis set in the Atlantic Ocean. The Greeks picked up the story, which is found in its most complete form in Plato's dialogues, Timaeus and Critias.

The Mycenaeans (c.1500-ll00 B.C.E.)

were Greeks from the mainland who took advantage of the Minoans' weakened state to conquer Crete and assume Minoan dominance of the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean. They were a vigorous and active people who engaged in trade and some piracy over a wide area extending from southern Italy in the west to Troy and the Black Sea in the northeast. We are almost as much in the dark about Mycenaean history and society as we are about the Minoans. We do have some written records in a script called Linear B which concern themselves mainly with official tax records and inventories.Three types of evidence tell us at least a little about Mycenaean society. First of all, we know that they were divided into different city-states such as Mycenae, Pylos, Tiryns, and Athens. Most of these consisted of highly fortified central palace complexes which ruled over surrounding villages. The Mycenaeans tried to run these as highly centralized states such as existed in Egypt and Mesopotamia. We do not know if these city-states were completely independent or looked to one city, probably Mycenae, for leadership. However, sources, such as the Iliad tell us that the Mycenaeans could apparently unite in a common endeavor such as the Trojan War.

Second, the art, armor, and remains of fortifications, such as those at Mycenae, tell us the Mycenaeans were much more warlike than the Minoans. Later Greeks had no idea of the existence of Mycenaean civilization and thought these massive walls and gates had been built by a mythical race of giants known as the Cyclopes.

Finally, archaeological remains also tell us that the Mycenaeans, at least the upper classes, were fabulously wealthy from trade and probably occasional piracy. Gold funeral masks, jewelry, bronze weapons, tripods, and a storeroom with 2853 stemmed goblets all attest to the Mycenaeans' wealth. Keep in mind this is only what we have found. There is no telling how much of their wealth was plundered by grave robbers.

Around 1200 B.C.E., a period of migrations and turmoil began that would weaken and eventually help destroy Mycenaean civilization. Once again, the main troublemakers were the Sea Peoples whom we have seen destroy the Hittite Empire, conquer the coast of Palestine, and shake the Egyptian Empire to its very foundations. The Sea Peoples also hit the Mycenaeans, destroying some settlements and driving other inhabitants inland or across the sea away from their raids. The historical Trojan War and sack of Troy took place at this time at the hands of the Mycenaeans, who may have been running from and, in some cases, joining up with the Sea Peoples. Hittite records associate their own decline with people known as the Ahhiwaya, translated as "Achaeans" (Greeks).

Whatever role the Mycenaeans may have played in all these raids, the result was widespread turmoil as cities were sacked, populations displaced, and trade disrupted. Even though the Mycenaeans survived the actual onslaught of the Sea Peoples, they did not survive the aftermath of all this destruction. Reduced revenue from trade may have caused more warfare between the city-states over the meager resources left in Greece. This warfare would only serve to weaken the Mycenaeans further, wreck trade even more, aggravate grain shortages at home, and so on. This recurring feedback of problems opened the way for a new wave of Greek tribes, the Dorians, to move down and take over much of Greece. A period of anarchy and poverty now settled over the Greek world which virtually blotted out any memories of the Minoans and Mycenaeans. However, on top of the foundations laid by these early Greek cultures an even more creative and vibrant civilization would be built, that of the classical Greeks.

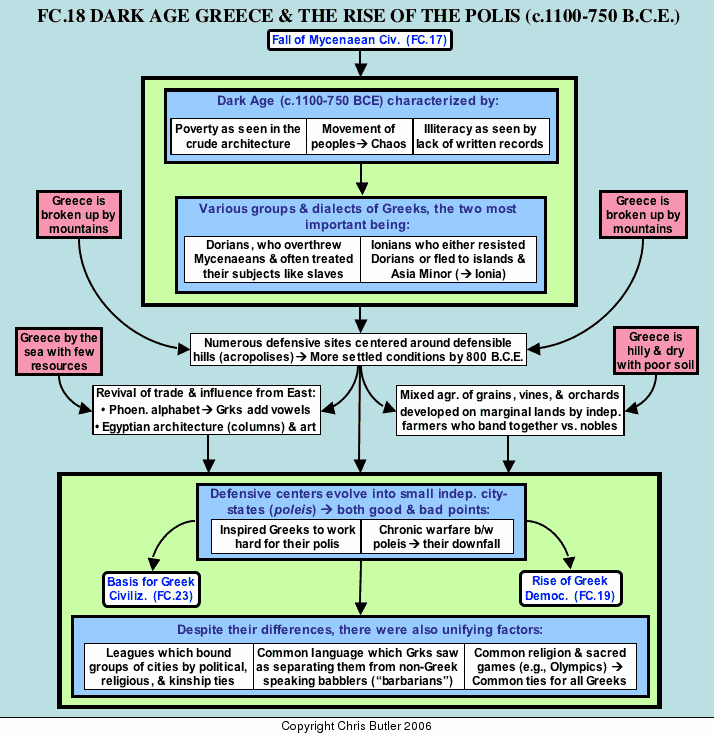

FC18The Dark Age of Greece & the Rise of the Polis (c.1100-750 BCE)

Introduction: the Dark Age of Greece

The centuries following the fall of the Mycenaeans are mostly obscured from our view by an extreme scarcity of records. As a result, this is known as the Dark Age of Greek history. Still, there are a few things that we know about this period that saw the transition from Mycenaean to classical Greek civilization. It was a period of chaos and the movements of peoples. New tribes of Greeks, the Dorians, moved in and displaced or conquered older inhabitants. Those peoples in turn would migrate, oftentimes overseas, in search of new homes. It was also a period of illiteracy and poverty leaving us no written records or sophisticated monuments to tell us about the culture of this period.

All this led to the Greek world at this time being divided up between various Greek-speaking peoples who were distinguishable from each other by slight differences in dialect and religious practices. However, their similarities were important enough so that we can talk about the Greeks as a people. Two of these Greek peoples in particular should be mentioned: the Dorians and Ionians. The Dorians were Greek invaders who came down from the north to conquer many of the Mycenaean strongholds around 1100 B.C.E. Sometimes they completely blended in with their pre-Dorian subjects, and there was little class conflict in their city-states. In other places the Dorians did not intermarry and remained a distinct ruling class over the non-Dorian population. The most extreme cases of this were Sparta and Thessaly, where the non-Dorians were virtually enslaved and forced to work the soil for the ruling Dorians. Such situations posed a constant threat of violence within city-states.

The Ionians were pre-Dorian inhabitants who avoided conquest by the Dorians, either by fighting them off or by migrating. The region of Attica, centered around Athens, was one main pocket of resistance to Dorian conquest, as seen in the myth of the Athenian king, Codrus, who sacrificed himself in battle to ensure Athens' safety against a Dorian invasion. Many Ionians either chose to migrate overseas or were forced to do so by invaders. Most of them settled in the Cycladic Islands or on the western coast of Asia Minor, which became known as Ionia from the large number of Ionian Greeks there.

The birth of the Polis

The chaos and Greece's mountainous terrain forced people to huddle under the protection of a defensible hill known as an acropolis. By 800 B.C.E., these fortified centers had produced more security and settled conditions that triggered two important developments vital to the emergence of Greek culture. First, the more settled conditions plus the fact that Greece was by the sea and had few resources led to a revival of trade and contact with the older cultures to the East. For example, the Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet and added vowels to it, so literacy returned to Greece. Also, Egyptian influence can be seen in Greek architecture and sculpture. Here too we see the Greeks would add their own innovations, giving their pillars more slender and graceful lines, and creating more lifelike statues than the stiff formal Egyptian models they had to copy. These influences would lead to and be the partial basis of classical Greek civilization .

Also, the settled conditions along with Greece's poor soils and hilly and dry conditions led to a new type of agriculture and farmer at this time. Instead of the overly centralized agriculture of the Mycenaean period and the under-worked aristocratic estates of the earlier Dark Age, farmers started developing less desirable lands which the nobles probably did not even want. Rather than raising just grain crops or grazing livestock, they developed a mixed agriculture of grains, orchards, and vineyards that was better adapted to the varied conditions of their lands and climate. The intensive labor such farms required bred very independent farmers who would be largely responsible for the emergence of democracy in the Greek polis.

The revival of trade and development of small independent farms also combined to allow the settlements to grow into towns and cities (poleis) that spread out beyond the confines of their original acropolises. Later, in some cities, notably Athens, the acropolis would become a place to build temples to the gods while also serving as a reminder of earlier more turbulent times. In order to understand the Greeks, one must understand what this most distinctive of all Greek institutions, the polis (city-state), meant to them.

The word polis means city, but it was much more than that to the Greek citizen. It was the central focus of his political, cultural, religious, and social life. Much of this was because the Greek climate was ideal for people to spend most of their time outdoors. Therefore, they interacted with one another much more than we do and became more tightly knit as a community. Since poleis were so isolated from each other by mountains, they became largely self sufficient and self-conscious communities. Greeks generally saw their poleis as complete in themselves, not needing to unite with other Greek poleis for more security or fulfillment. We can see three main qualities that were typical of major and minor poleis alike.

-

The polis was an independent political unit with its own foreign policy, coinage, patron deity, and even calendar. For example, the tiny island of Ceos off the coast of Attica, had four independent city-states, each claiming the right to carry on its own business and wage war as it saw fit-- all this on an island no more than ten miles in length!

-

The polis was on a small scale. This is obvious from the example of Ceos. But consider a major city-state such as Corinth, which controlled an area of only some 320 square miles, considerably smaller than an average county in one of our states. Athens, by far the most influential of the city-states on our own culture, controlled an area only about the size of Rhode Island. Yet it is to Athens that we look for the birth of such things as our drama, philosophy, architecture, history, and democracy.

-

The polis was personal in nature. This follows logically from its small size. Greek philosophers such as Aristotle and Plato thought that a polis should be small enough for every citizen to know every other citizen. If it got any bigger, it would get too impersonal and not work for the individual citizen's benefit. Even in Athens, the most populous Greek city-state, some citizens could pay their taxes in very personal ways, such as by equipping and maintaining a warship for a year or by producing a dramatic play for the yearly festival dedicated to Dionysus. This tended to breed a healthy competition where citizens would strive to make their plays or warships the best ones possible, thus benefiting the polis as a whole.

The polis' small and personal nature bred an intense loyalty in its citizens that had both its good and bad points. On the plus side, it did inspire members of the community to work hard for the civic welfare. The incredible accomplishments of Athens in the fifth century B.C.E. are the most outstanding example of what this civic pride could accomplish.

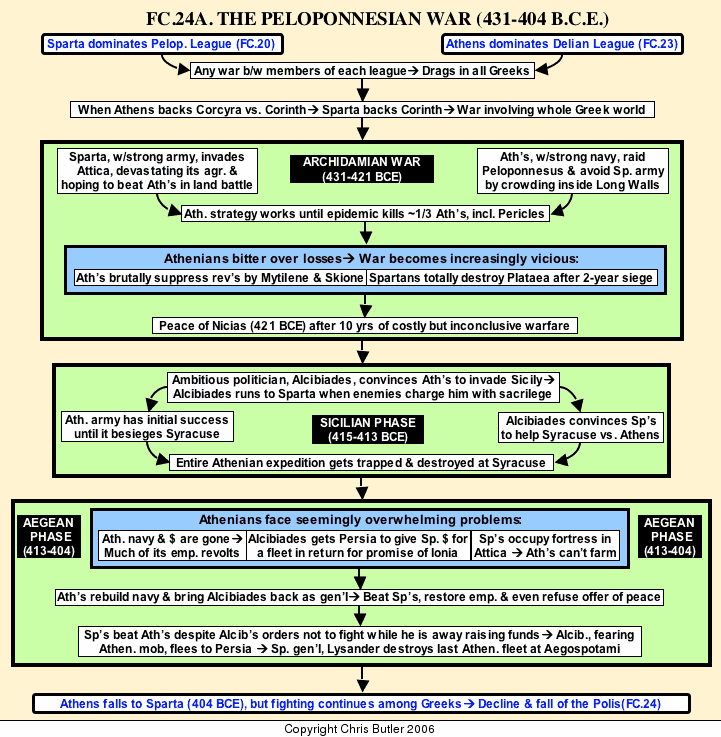

On the negative side, the polis' narrow loyalties led to intense rivalries and chronic warfare between neighboring city-states. These wars could be long, bitter, and costly. Sparta and Argos were almost always in a state of war with each other or armed truce waiting for war. The Peloponnesian War between Sparta and Athens lasted 27 years, destroying Athens' empire and golden age. Sometimes city-states would be entirely destroyed in these wars, such as happened to Plataea and Sybaris. In addition, there was often civil strife within the city-state as well: between rich and poor, Dorians and non-Dorians, and citizens and non-citizens. This internal turmoil could be every bit as vicious and bloody as fighting between city-states. Ultimately, the Greeks sealed their own doom by wasting energy and resources in their own petty squabbles while other larger powers were waiting in the wings for the right moment to strike.

However, there were several factors that gave the Greeks a common identity and some degree of unity. First of all, the Greeks spoke a common language that largely gave them a common way of looking at things. The Greeks generally divided the world into those who spoke Greek and those who did not. Those who did not speak Greek were called barbarians, since, to the Greeks, they senselessly babbled ("bar-bar-bar").

Religion also gave the Greeks a common identity. Athletic contests in honor of the gods especially emphasized the Greeks' unity as a people. The most famous of these were the Olympic Games held every four years in honor of Zeus. During these games a truce was called between all Greek city-states, allowing Greeks to travel in peace to the games, even through the territory of hostile states. The modern Olympic Games, even though they are no more successful than the ancient games in putting an end to war, still serve as a symbol of peace in a less than peaceful world.

Finally, several city-states might combine into leagues. These leagues might be purely for the purpose of celebrating religious rites or kinship common to their cities. A good example was the Delphic Amphictyony, a league of twelve cities formed to promote and protect the Oracle of Delphi. Some leagues were for political and defensive purposes. The Peloponnesian League under Sparta and the Delian League under Athens were for such a purpose and together claimed the loyalties of most of the city-states in Greece and Ionia. This was good for preventing war between individual city-states. But it backfired when Sparta and Athens went to war in 431 B.C.E. and dragged most of the Greek world into the most tragic and destructive struggle in ancient Greek history.

By 750 B.C.E., the Greek world had largely taken shape as a collection of city-states, often at war with one another, but also feeling certain common ties of language, religion, and customs. At this point, there was nothing remarkable about the Greeks, but forces were at work that would transform Greece into the home of democracy and the birthplace of Western Civilization.

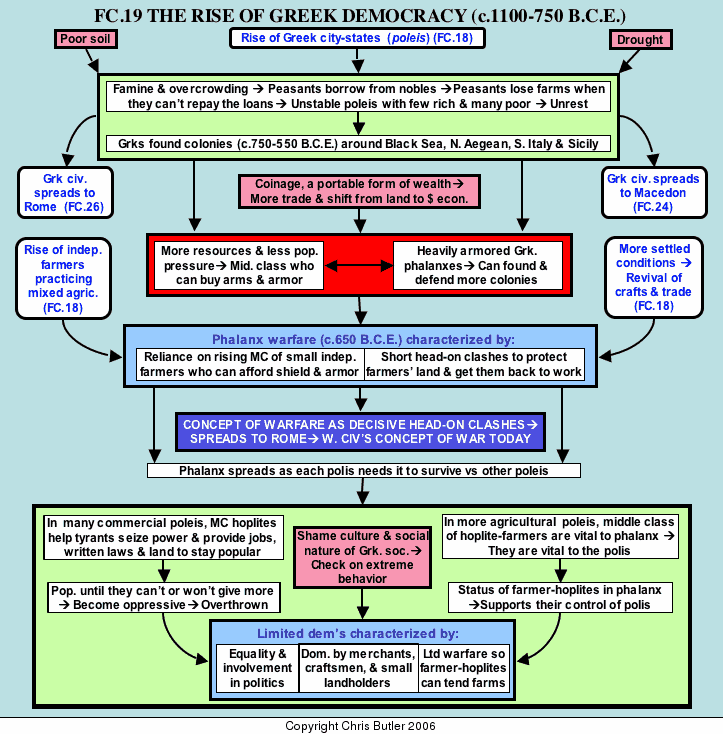

FC19The Rise of Greek Democracy (c.750-500 BCE)

The Age of Colonization (c.750-550 B.C.E)

Greece was not a rich land capable of supporting a large population. Yet the revival of stable conditions and the rise of a new class of independent farmers practicing a mixed agriculture of grains, vines, and orchards after 800 B.C.E brought population growth. This, in turn, brought problems, since family lands had to be split up among the surviving sons. These sons also had families to support, but on less land than their fathers had. Greece's poor soil and occasional droughts would lead to famines, forcing the victims of those crop failures to seek loans from the rich nobles. Of course, there was interest on the loan, generally equal to one-sixth of the peasants' crops. Failure to pay back the loan and interest in time led to the loss of the family lands or the personal freedom of the farmer and his family. Unfortunately, bad harvests often run in cycles of several years at a time. As a result, the Greek poleis in the eighth century B.C.E had a few rich nobles and a multitude of desperately poor people, creating an unstable situation for the polis and the nobles who controlled it. Therefore, many city-states started looking for new lands on which to settle their surplus populations. The Age of Colonization was born.

The Greeks looked for several qualities in a site for a colony: good soil, plentiful natural resources, defensible land, and a good location for trade. They especially found such sites along the coasts of the North Aegean and Black Seas to the northeast, and Sicily and Southern Italy to the west. However, Greek colonies dotted the map of the Mediterranean from Egypt and Cyrene in North Africa to Spain and Southern France in the West.

Founding a colony was no easy task. A leader and enough settlers had to be found, which often involved two city-states combining their efforts to found the colony. Finding a site for the colony was also a problem. Generally, colonists would ask the Oracle of Delphi for advice, usually getting a vague double-edged answer that could be interpreted in several ways, thus making the Oracle always right. For example, the colonists who founded Byzantium by the Black Sea were told to found their city across from the blind men. They figured the blind men were the settlers of nearby Chalcedon who had missed the much superior site of nearby Byzantium, since it controlled the trade routes between the Black and Aegean Seas and between Europe and Asia.

Although a colony was an independent city-state in its own right, it generally kept close relations with its mother city ( metropolis), symbolized by taking part of the metropolis' sacred fire, representing its life, to light the fire of the new colony. Eventually, many Greek colonies, especially ones to the west such as Syracuse, Tarentum, and Neapolis (Naples), would surpass their mother cities in wealth and power. As a result, Southern Italy and Sicily came to be known as Magna Graecia, (Greater Greece).

Colonies triggered a feedback cycle that would help maintain the colonial movement and lead to dramatic economic, social, and political changes in the Greek homeland. First of all, colonies relieved population pressures at home and provided resources to their mother cities. This helped support the emergence of craftsmen who made such things as pottery and armor for export. It also made life easier for the free farmers who had more land now that there was less crowding. These two rising groups, craftsmen and free farmers, constituted a new group, the middle class, which could afford arms and armor and help defend their poleis.

That, in turn, allowed the Greeks to deploy into a phalanx, a much larger mass formation of heavily armored soldiers who together formed a sort of human tank. Thanks to this deadly new formation, the Greeks were better able to found and defend colonies in territories with large hostile populations. This would feed back into the beginning of the process whereby colonies would produce more wealth and resources that would add further to the rising middle class that could afford arms and armor, leading to more heavily armed Greeks who could found and defend more colonies, and so on.

Another development that helped this process was a new invention: coinage. Although for centuries, people had used gold and silver as common mediums of exchange to expedite trade, there were always problems of determining the accurate weight and purity of such metals to avoid being cheated. Then, around 600 B.C.E., the Lydians, neighbors of the Ionian Greeks in Asia Minor, issued the first coins, lumps of gold marked with a government stamp guaranteeing the weight and purity of those lumps. Greek poleis soon picked up on this practice and issued their own coins. Coinage created a more portable form of wealth that everyone agreed was valuable. Trade became much easier to carry on, thus increasing its volume and the fortunes of the merchants involved in it. Overall, this signaled a growing shift from the land-based economy dominated by the nobles to the more dynamic money economy controlled by the middle class.

The Western way of war

The cycle of colonization spread a new type of warfare across the Greek world. Previously, Greek warfare had been the domain of the nobles, since they were the only ones who could afford the arms and armor necessary for fighting in the front lines. While this put the brunt of the fighting on their shoulders, it also gave them prestige and power, since they had the weapons to enforce their will.

However, by the mid seventh century B.C.E, the wealth brought in by colonies led to a new type of warfare, the hoplite phalanx, a compact formation of heavily armored soldiers (hoplites, from the Greek word for shield) with overlapping shields and armed with spears. The idea was to use the weight of the phalanx to plow through the enemy. It wasn’t elegant, but it was effective and brought into play two new revolutionary factors. First, since the phalanx’s success relied on numbers, anyone able to afford heavy armor and shield had to be used. This meant including the rising middle class of independent farmers, craftsmen, and merchants, which would have a dramatic impact on the polis’ political structure in the future.

Secondly, the hoplite phalanx created a new concept of warfare. Previously, when warfare had been primarily a matter of honor and power for a narrow group of kings and nobles who had nothing better to do, battles had mainly been a matter of hit-and-run tactics with some face-to-face combat. However, with middle class farmers now making up the bulk of the phalanx, warfare became a matter of defending their very livelihood. Therefore, the practice developed of meeting invaders in short, but brutal, head-on clashes to protect the defending farmers’ lands and homes from ruin. Also, the fact that most of those fighting the battles had regular occupations to get back to reinforced this urge for a quick resolution of a war in one decisive battle.

This concept of resolving wars in decisive head-on clashes long outlived the Greek poleis that started it. The Romans would subscribe to this principle with systematic efficiency and pass it on to Western Civilization where it is still seen as the way to fight wars. Until the mid 1900s this strategy served Western powers well, but in recent decades it has not always proven effective, as the Vietnam War, Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, and American occupation in Iraq have shown.

Pheidon, the ruler of Argos, was the first to use the new hoplite phalanx against Sparta, defeating it in the process. Soon Sparta had adapted to these new tactics, and other Greek poleis quickly proceeded to arm their middle classes and form phalanxes of their own in order to survive. Soon the "Hoplite Revolution" had spread throughout Greece and its colonies.

By 550 B.C.E, the cycle of Greek colonization was running out as few good sites for new colonies remained. However, colonization had spread of Greek civilization to other peoples, notably the Macedonians to the north and the Romans to the west. Rome in particular would adapt Greek culture to its own needs and pass it on to Western Civilization.

The rise of Greek democracy

Increased prosperity oftentimes leads to trouble, for it creates expectations of power and status to go with it. People who have virtually nothing expect nothing more. People who have had a taste of something generally expect more and will even fight to get it. Such is the fuel of revolutions, and ancient Greece was no exception. The problem was that, while the middle class artisans and farmers had little or no social status or political power to go with the expectation to fight in the phalanx. Their frustration in more commercial poleis played itself out somewhat differently than in the more agricultural poleis, but ultimately with the same basic result.

In many, usually the more commercial poleis such as Corinth, Megara, and Athens, some disgruntled and ambitious nobles used the frustrated middle class to seize power from the ruling aristocracy. The government they set up was called a tyranny, from the Greek word tyrannos, meaning one-man rule. Such an arrangement was usually illegal, but not necessarily evil. That association with the word tyrant would come later.

In order to maintain his popularity, the tyrant typically did three things. First, he protected peoples' rights with a written law code, literally carved in stone, so that the laws could not be changed or interpreted upon the whim of the rich and powerful. Second, he confiscated the lands of the nobles he had driven from power and redistributed them among the poor. Finally, he provided jobs through building projects: harbors, fortifications, and stone temples with graceful fluted columns, a new Greek innovation. In addition, tyrants had the means to patronize the arts. Thus the sixth century B.C.E. saw a flourishing of Greek culture in such areas as architecture, sculpture, and poetry.

However, the increased prosperity brought on by the tyrants only gave the people a taste for more of the same. By the second or third generation, tyrants could not or would not meet those growing demands, and people grew resentful. In reaction to this resentment, tyrants would often resort to repressive measures, which just caused more resentment, more repression, and so on. Eventually, this feedback of resentment and repression would lead to a revolution to replace the tyrants with a limited democracy especially favoring the hoplite class of small landholding farmers, though excluding the poor, women, and slaves.

In the more agricultural poleis, the farmer-hoplites seem to have taken control more peacefully. Their dual status as farmers and hoplites supported each other in maintaining control. As farmers, they were the ones who could afford arms and armor and serve in the phalanx. And as hoplites in the phalanx, they were the ones with the power to run the state. Much like the states that experienced tyrannies, these agrarian poleis also established limited democracies favoring the small land-holding farmers. While these democracies may have excluded a majority of their populations, they did exhibit several characteristics that made them a unique experiment in history and a giant step toward democracy.

-

A high value was placed on equality, at least among the citizens ruling the polis. This ethos of equality discouraged the accumulation of large fortunes and encouraged the rich to donate their services and wealth to the polis. This created a fine balance between individual rights and working for the welfare of the society as a whole that helped create fairly stable poleis.

-

The polis was largely dominated by a middle class of small landholders, merchants, and craftsmen. In addition to women and slaves, Greek democracies typically excluded freemen without any property from the full advantages of citizenship. However, despite its shortcomings, the moderate style of democracy born in Greece by 500 B.C.E was the basis for the later, much more broadly based democracy in Athens and our own idea of individuals controlling their own destinies.

-

Hoplite warfare limited the scope and damage of warfare among the Greek poleis. Since it was the farmers who both declared war and fought it for the polis, they made sure that it was short and decisive so it would not disrupt their agricultural work or damage their crops. A typical war might take only three days: one day to march into enemy territory, one day to fight, and one day to get back home to the crops. They also made sure it was cheap. Since hoplite warfare was simple and everyone supplied his own equipment and rations, there was no need for taxes to support generals and buy supplies. This limited, almost ritualistic, style of warfare maintained a stability among the Greek poleis despite the frequency of their wars.

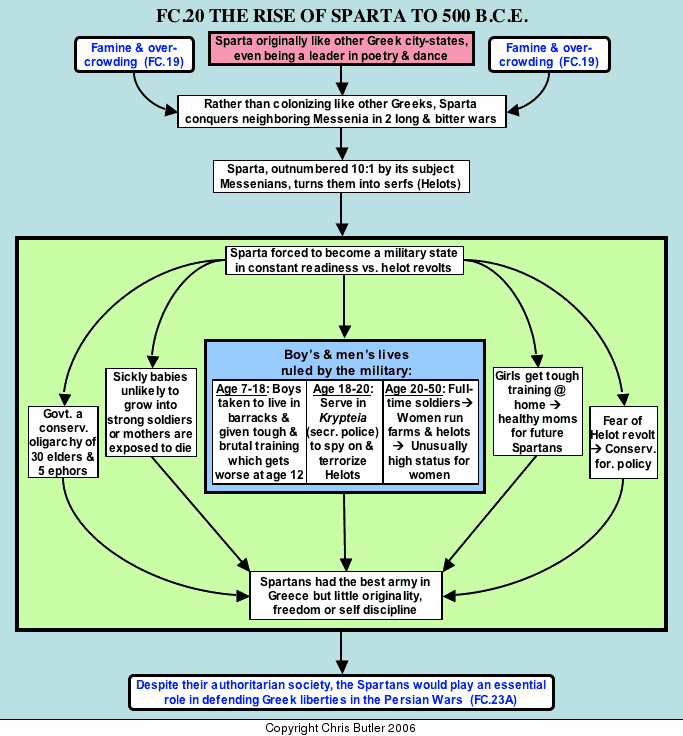

FC20The Rise of Sparta to 500 BCE

Come home with your shield or on it.— Spartan women, to their men leaving for battle

No Greek city-state aroused such great interest and admiration among other Greeks as Sparta. This was largely because the Spartans did about everything contrary to the way other Greeks did. For example, Sparta had no fortifications, claiming its men were its walls. While other Greeks emphasized their individuality with their own personal armor, the Spartans wore red uniforms that masked their individuality and any blood lost from wounds. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that we remember Sparta for being a military state always ready for war, but not against other city-states so much as against its own enserfed subjects.

Originally, Sparta was much like other Greek city-states, being a leader in poetry and dance. However, by 750 B.C.E., population growth led to the need for expansion. Instead of colonizing overseas, like other Greeks did, the Spartans decided to attack their neighbors, the Messenians. In two bitterly fought wars, they subdued the Messenians and turned them into serfs ( Helots) who had to work the soil for their masters. Unfortunately for the Spartans, the Helots vastly outnumbered them.

As a result, Sparta became a military state constantly on guard against the ever-present threat of a Helot revolt. This especially shaped five aspects of Spartan society: its infants, its boys, its girls, its government, and its foreign policy. Infants were the virtual property of the state from birth when state inspectors would examine them for any signs of weakness or defects. Babies judged unlikely to be able to serve as healthy soldiers or mothers were left to die on nearby Mt. Taygetus.

Boys were taken from home at age seven to live in the barracks. There they were formed into platoons under the command of an older man and the ablest of their number. Life in the barracks involved a lot of hard exercise and bullying by the older boys. At age twelve it got much worse. Adolescence brought the Spartan training at its worst. The boys received one flimsy garment, although they usually trained and exercised in the nude. They slept out in the open year round, only being allowed to make a bed of rushes that were picked by hand, not cut. They were fed very little, forcing them to steal food to supplement their diet and teaching them to forage the countryside as soldiers. Their training, games, and punishments were all extremely harsh. One notorious contest involved tying boys to the altar of Artemis Orthia and flogging them until they cried out. Reportedly, some of them kept silent until they died under the lash.

At age eighteen, the Spartan entered the Krypteia, or secret police, for two years. The Krypteia's task was to spy on and terrorize the Helots in order to keep them from plotting revolt. The Spartans even declared ritual warfare on the Helots each year to remind themselves and the Helots of their situation and Spartan resolve to deal with it. At age twenty, the Spartan entered the army where he would spend the next thirty years. As an adult, he could grow his hair shoulder length in the Spartan fashion to look more terrifying to his enemies. Not surprisingly, he had little in the way of a family life. However, it was illegal not to marry in Sparta, since it was part of the Spartan's duty to produce strong healthy children for the next generation. After getting married, the young husband might have to sneak out of the barracks at night in order to see his wife and children. It was said some Spartan fathers went for years without seeing their families by the light of day. At age fifty, the Spartan could finally move home, although he remained on active reserve for ten more years.

Girls did not have it much easier. Although they did live at home rather than in the barracks, they also went through arduous training and exercise. All of this was for one purpose: to produce strong healthy children for the next generation. Surprisingly, Spartan women were the most liberated women in ancient Greece. This was because the men were away with the army, leaving the women to supervise the Helots and run the farms. In fact, Spartan women scandalized other Greeks with how outspoken and free they were.

Spartan government, in sharp contrast with the democracies found in other city-states, kept elements of the old monarchy and aristocracy. They had two kings whose duty was to lead the army. Most power rested with five officials known as ephors and a council of thirty elders, the Gerousia. There was also an assembly of all Spartan men that voted only on issues the Gerousia presented them. The Spartans had a very conservative foreign policy, since they did not want to risk a Helot revolt while they were away at war. They did extend their influence through leadership of the Peloponnesian League, which contained most of the city-states in the Peloponnesus, making Sparta the most powerful Greek city-state, although its army was never very large.

Spartan discipline did produce magnificent soldiers, inured to hardship and blind obedience to authority, but with little talent for original thinking or self-discipline. However, in the Persian wars, the Spartans would do more than their share in the defense of freedom, as ironic as that may have sounded to them.FC21Early Athens to c.500 BCE

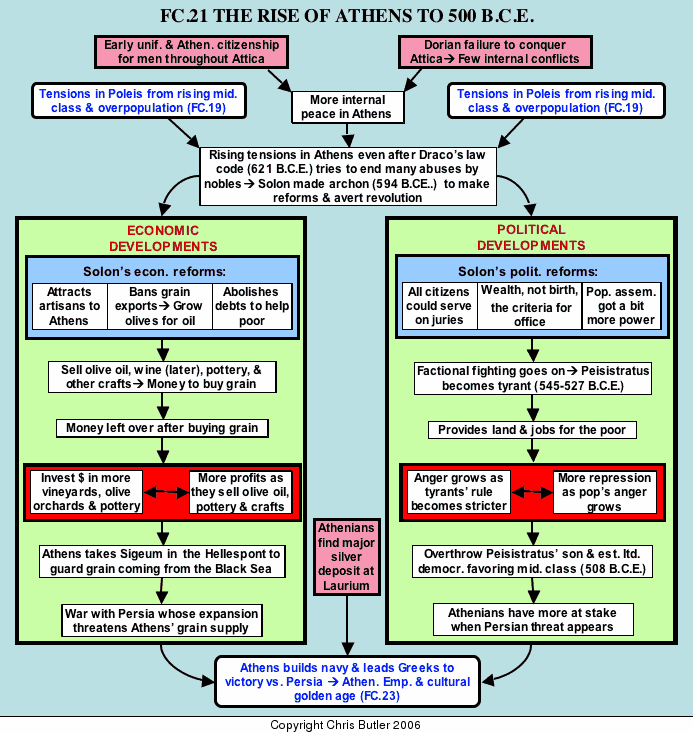

While Athens is the city we generally think of when the Greeks are mentioned, it did not always seem destined for glory. Rather, its greatness was the product of a long history laying the foundations for the great accomplishments of the fifth century B.C.E.

Two things in Athens' early history led to internal peace that made its history and development much easier. First of all, there was no Dorian conquest of Attica, the region surrounding Athens. The myth of the Athenian king, Codrus, who sacrificed himself in battle against the Dorians tells us there probably was Dorian pressure on Attica, but that it failed. Consequently, with no conflict of Dorians against non-Dorians, internal peace could reign in Athenian society. Second, Athens united all of Attica under its rule at a fairly early date and made all its subjects Athenian citizens. Therefore, they were more likely to work for Athens' interests in contrast to the Spartan Helots who were always looking for an opportunity to revolt.

Despite these advantages, the tensions that accompanied both a rising middle class and overpopulation in other poleis affected Athens as well. For example, there was a failed attempt to establish tyranny at Athens by a man named Cylon who seized the Acropolis with the aid of Megarian troops.

One issue causing discontent was the lack of a written law code. Since nobles controlled the religion, which was seen as the source of law, they could say the law was whatever they pleased and then change it at will. At last, in 62l B.C.E., they gave in and commissioned Draco, whose name meant "dragon", to write down the laws. His law code was so harsh that even today we use the term "draconian" to describe something extremely severe. Some people claimed Draco's law code was written in blood rather than ink. But Draco did get the laws written down, which was a step forward for the people. And, of course, they wanted more.

By 600 B.C.E., the nobles in Athens were becoming more nervous as the complaints of the very poor and the rising middle class grew increasingly louder. As a result, they gave a man named Solon extraordinary powers to reform the state and ease the tensions between the different classes. Solon passed both economic and political reforms that laid the foundations for Athens' later greatness.

Economic reforms

Solon improved Athens' economy in several ways. First, since Attica's soil was particularly poor for farming wheat and barley, he outlawed the export of grain from Attica. This encouraged the cultivation of olive trees that were better suited for Attica's soil. The olive oil produced from these trees was a valuable commodity used for cleansing and as a fuel for light and cooking. Later, grapevines would also be cultivated, and Attica's wine became still another highly valued Athenian product. Second, Solon developed trade and manufacture in Athens, largely through attracting skilled craftsmen to settle there. He especially encouraged pottery since Attica had excellent clay for ceramics. In later years, Athenian pottery would come to be some of the most beautiful and highly valued in the Mediterranean. One other thing Solon did to relieve the poverty in Athens was to abolish debts and debt slavery. While this was not popular with the nobles, it did ease some of the tensions threatening Athenian society at that time.

The profits gained from selling olive oil, pottery, and wine were then used for buying grain from the Black Sea. Since Athens' economy now was much more suited to local conditions than when it was barely getting by on the old subsistence agriculture, it could buy the grain it needed and still have money left over. The Athenians could use this extra money for further developing their economy through more trade, industry, and olive orchards. This would lead to even more profits, and so on.

Solon's reforms set the stage for the Persian Wars and Athens' later cultural accomplishments. Since Athens was heavily dependent on the Black Sea for grain, it was very sensitive to any events in that part of the world, just as the United States today is sensitive to events in Middle East where it gets much of its oil. As a result, Athens expanded to the shores of the Black Sea, thus leading to a collision with Persia over control of that region.

Solon's political reforms

made the Athenian state more democratic in three ways. First, he changed the qualifications for holding public office from being determined by birth into a particular class to how much wealth one had. This meant that someone not born a noble still had a chance to rise up through society by means of his ability. Solon also admitted the poorest class of citizens to participate in the popular assembly and juries. Finally, he granted a few powers and privileges to the popular assembly, which opened the way for more sweeping democratic reforms a century later.These measures delayed, but did not prevent, the overthrow of the aristocrats by a tyrant. Fighting in Athens continued between the Hill (peasants on small farms), Shore (artisans and traders), and Plain (nobles) factions. Eventually, the leader of the hill faction, Peisistratus, gained the upper hand and became tyrant. Peisistratus did two things important for Athens' future. For one thing, like other Greek tyrants, he enriched the lower classes by providing them with land and jobs on building projects. Second, he secured Athens' grain supply from the Black Sea by getting control of the town of Sigeum, which safeguarded Athens' grain ships in that area but also set Athens up for an eventual clash with Persia.

There were also cultural developments during Peisistratus' rule. For one thing, he gathered scholars to take all the different versions of Homer's Iliad and decide which was the definitive one. One other cultural accomplishment was the invention of tragic drama. This evolved from rather boisterous goat songs ( tragoidea) dedicated to Dionysus, the god of song and revelry. However, by this time, these songs had become much more serious, and the addition of an actor to interact with the chorus of fifty led to the birth of drama.

As we have seen, in most poleis the first generation of tyrants would rule rather peacefully. For example, Cypselus, tyrant of Corinth, was so popular that he went about without so much as a bodyguard. However, the second or third generation of tyrants usually ran into problems, either because their rule was oppressive or people wanted more political rights to go along with their rising wealth. Athens was no exception. Peisistratus ruled and died peacefully, but his son, Hippias, ruled more oppressively, especially after an unsuccessful assassination attempt aroused his suspicions of all around him. Popular anger would grow, triggering more oppression, causing more anger, and so on. Finally, Hippias was driven out of Athens with help from the Spartans who then put a garrison of 700 soldiers in Athens' Acropolis. However, the Spartans were hardly the people to go along with the democratic aspirations of the Athenians, and their garrison had to be driven out of the Acropolis before democracy could be established. The man who did this, Cleisthenes, was also responsible for setting up a stable democracy at Athens.

Cleisthenes saw clearly that the friction between the factions of Hill, Shore, and Plain and between the four different tribes had to be stopped. He cleverly did this by breaking up the old tribes and replacing them with ten artificial tribes comprised of elements from different tribes and factions. Artificially mixing people from different loyalties tended to break up those old loyalties, leaving only loyalty to Athens. Cleisthenes also made the popular assembly the main law making body. The democracy that emerged, much like those in other poleis of the time, was a somewhat limited one favoring the middle class of farmers, merchants and craftsmen. However, it was still a democracy, which meant the Athenians had more than ever at stake Athens' security.

Therefore, the combination of this greater sense of commitment to Athens, the struggle with Persia over the security of the Black Sea grain supply, and the fortunate discovery of large deposits of silver at Laurium in Attica, would prompt the Athenians to use their economic power to build a navy with which to fight Persia. It was this navy which would lead the Greeks to victory over Persia and lay the foundations for the Athenian Empire in the fifth century B.C.E. That empire in turn would provide the wealth to support the cultural flowering at Athens that has been the basis for so much of Western Civilization.

FC22Greek Philosophy from Thales to Aristotle (c.600-300 BCE)

Introduction

When people think of the ancient Greeks, they usually think of such things as Greek architecture, literature, and democracy. However, there is one other contribution they made that is central to Western Civilization: the birth of Western science.

There were three main factors that converged to help create Greek science. First of all, there was the influence of Egypt, especially in medicine, which the Greeks would draw heavily upon. Second, Mesopotamian civilization also had a significant impact, passing on its math and astronomy, including the ability to predict eclipses (although they did not know why they occurred). Third, there was the growing prosperity and freedom of expression in the polis, allowing the Greeks to break free of older mythological explanations and come up with totally new theories. All these factors combined to make the Greeks the first people to give non-mythological explanations of the universe. Such non-mythological explanations are what we call science.

However, there were also three basic limitations handicapping Greek scientists compared to scientists today. For one thing, they had no concept of science as we understand it. They thought of themselves as philosophers (literally "lovers of wisdom") who were seeking answers to all sorts of problems about their world: moral, ethical, and metaphysical as well as physical. The Greeks did not divide knowledge into separate disciplines the way we do. The philosopher, Plato, lectured on geometry as well as what we call philosophy, seeing them as closely intertwined, while Parmenides of Elea and Empedocles of Acragas wrote on physical science in poetic verse. Second, the Greeks had no guidelines on what they were supposed to be studying, since they were the first to ask these kinds of questions without relying on religious explanations. However, they did define certain issues and came up with the right questions to ask, which is a major part of solving a problem. Finally, they had no instruments to help them gather data, which slowed progress tremendously.

The Milesian philosophers

Greek science was born with the Ionian philosophers, especially in Miletus, around 600 B.C.E. The first of these philosophers, Thales of Miletus, successfully predicted a solar eclipse in 585 B.C.E., calculated the distance of ships at sea, and experimented with the strange magnetic properties of a rock near the city of Magnesia (from which we get the term "magnet"). However, the question that Thales and other Ionian philosophers wrestled with was: What is the primary element that is the root of all matter and change? Thales postulated that there is one primary element in nature, water, since it can exist in all three states of matter: solid, liquid, and gas.

Thales' student, Anaximander, proposed the theory that the stars and planets are concentric rings of fire surrounding the earth and that humans evolved from fish, since babies are too helpless at birth to survive on their own and therefore must arise from simpler more self-sufficient species. He disagreed with Thales over the primary element, saying water was not the primary element since it does not give rise to fire. Therefore, the primary element should be some indeterminate element with built-in opposites (e.g., hot vs. cold; wet vs. dry). For lack of a better name, he called this element the "Boundless." Another Milesian, Anaximenes, said the primary element was air or vapor, since rain is pressed from the air.

The nature of change

All these speculations were based on the assumption there is one eternal and unchanging element that is the basis for all matter. Yet, if there is just one unchanging element, how does one account for all the apparent diversity and change one apparently sees in nature? From this time, Greek science was largely split into two camps: those who said we can trust our senses and those who said we cannot.

Among those who distrusted the senses was Parmenides of Elea, who, through some rather interesting logic, said there is no such thing as motion. He based this on the premise that there is no such thing as nothingness or empty space since it is illogical to assume that something can arise from nothing. Therefore, matter cannot be destroyed, since that would create empty space. Also, we cannot move, since that would involve moving into empty space, which of course, cannot exist. The implication was that any movement we perceive is an illusion, thus showing we cannot trust our senses.

On the other hand, there was Heracleitus of Ephesus, who said the world consists largely of opposites, such as day and night, hot and cold, wet and dry, etc. These opposites act upon one another to create change. Therefore not only does change occur, but is constant. As Heracleitus would say, you cannot put your foot into the same river twice, since it is always different water flowing by. However, since we perceive change, we must trust our senses at least to an extent.

A partial reconciliation of these views was worked out by two different philosophers postulating the general idea of numerous unchanging elements that could combine with each other in various ways. First, there was Empedocles of Acragas who said that the mind can be deceived as well as the senses, so we should use both. This led to his theory of four elements, earth, water, air, and fire, where any substance is defined by a fixed proportion of one or more of these elements (e.g., bone = 4 parts fire, 2 parts water, and 2 parts earth). Although the specifics were wrong, Empedocles' idea of a Law of Fixed Proportions is an important part of chemistry today.

In the fifth century B.C.E., Democritus of Abdera developed the first atomic theory, saying the universe consists both of void and tiny indestructible atoms. He said these atoms are in perpetual motion and collision causing constant change and new compounds. Differences in substance are supposedly due to the shapes of the atoms and their positions and arrangements relative to one another.

In the fifth century B.C.E., Athens, with its powerful empire and money, became the new center of philosophy, drawing learned men from all over the Greek world. Many of these men were known as the Sophists. They doubted our ability to discover the answers to the riddles of nature, and therefore turned philosophy's focus more to issues concerning Man and his place in society. As one philosopher, Protagoras, put it, "Man is the measure of all things." Being widely traveled, the Sophists doubted the existence of absolute right and wrong since they had seen different cultures react differently to moral issues, such as public nudity, which did not bother the Greeks. As a result, they claimed that morals were socially induced and changeable from society to society. Some Sophists supposedly boasted they could teach their students to prove the right side of an argument to be wrong. This, plus the fact that they taught for money, discredited them in many people's eyes.

Socrates (470-399 B.C.E.)

was one of Athens' most famous philosophers at this time. Like the Sophists, with whom he was wrongly associated, he focused on Man and society rather than the forces of nature. As the Roman philosopher, Cicero, put it, "Socrates called philosophy down from the sky..." Unlike the Sophists, he did not see morals as relative to different societies and situations. He saw right and wrong as absolute and worked to show that we each have within us the innate ability to arrive at that truth. Therefore, his method of teaching, known even today as the Socratic method, was to question his students' ideas rather than lecture on his own. Through a series of leading questions he would help his students realize the truth for themselves.Unfortunately, such a technique practiced in public tended to embarrass a number of people trapped by Socrates' logic, thus making him several enemies. In 399 B.C.E., he was tried and executed for corrupting the youth and introducing new gods into the state. Although Socrates left us no writings, his pupil Plato preserved his teachings in a number of written dialogues. Socrates influenced two other giants in Greek philosophy, Plato and Aristotle, who both agreed with Socrates on our innate ability to reason. However, they differed greatly on the old question of whether or not we can trust our senses.

Plato (428-347)

was the first of these philosophers. He was also influenced by the early philosopher and mathematician, Pythagoras of Croton in South Italy, who is most famous for the Pythagorean theorem for finding the length of the hypotenuse in a right triangle. Pythagoras thought that all the principles of the universe were bound up with the mystical properties of numbers. He felt the whole universe can be perceived as a harmony of numbers, even defining objects as numbers (e.g., justice = 4). He saw music as mathematical and, in the process, discovered the principles of octaves and fifths. He also thought the universe orbited around a central fire, a theory that would ultimately influence Copernicus in his heliocentric theory 2000 years later.Plato drew upon Pythagoras' idea of a central fire and proposed there are two worlds: the perfect World of Being and this world, which is the imperfect World of Becoming where things are constantly changing. This makes it impossible for us to truly know anything, since this world is only a dim reflection of the perfect World of Being. As Plato put it, our perception of reality was no better than that of a man in a cave, trying to perceive the outside world through viewing the shadows cast against the wall of the cave by a fire. Since our senses alone cannot be trusted, Plato said we should rely on abstract reason, especially math, much as Pythagoras had. The sign over the entrance to Plato's school, the Academy, reflected this quite well: "Let no one unskilled in geometry enter."

Aristotle (384-322 B.C.E.)

was a pupil at Plato's Academy, but held a very different view of the world from his old teacher, believing in the value of the senses as well as the mind. Although he agreed with Plato on our innate power of reasoning, he asserted that nothing exists in our minds that does not first exist in the sensory world. Therefore, we must rely on our senses and experiment to discover the truth.Aristotle accepted the theory of four elements and the idea that the elements were defined on the basis of two sets of contrasting qualities: hot vs. cold, and wet vs. dry, with earth being cold and dry, water being cold and wet, air being hot and wet, and fire being hot and dry. Thus, according to Aristotle, we should be able to change substances by changing their qualities. The best example was heating cold and wet water to make it into hot and wet air (vapor). This idea would inspire generations of alchemists in the fruitless pursuit of a means of turning lead into gold.

Aristotle said the four elements have a natural tendency to move toward the center of the universe, with the heavier substances (earth and water) displacing the lighter ones (air and fire), so that water rests on land, air on top of water, and fire on top of air. He also said there was a celestial element, ether, which was perfect and unchanging and moved in perfect circles around the center of the universe, which is earth where all terrestrial elements are clustered.

Aristotle's theories of the elements and universe were highly logical and interlocking, making it hard to disprove one part without attacking the whole system. Although Aristotle often failed to test his own theories (so that he reported the wrong number of horse's teeth and men's ribs), his theories were easier to understand than Plato's and reinstated the value of the senses, compiling data, and experimenting in order to find the truth. Although Plato's theories would not be the most widely accepted over the next 2000 years, they would survive and be revived during the Italian Renaissance. Since then, the idea of using math to verify scientific theories has also been an essential part of Western Science. While both Plato and Aristotle had flaws in their theories, they each contributed powerful ideas that would have profound effects on Western civilization for 2000 years until the Scientific Revolution of the 1700's.

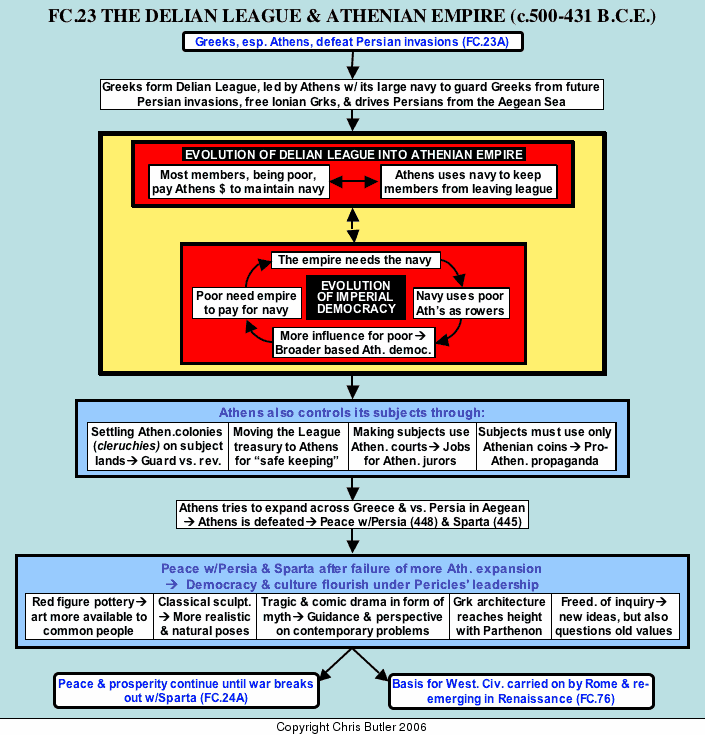

FC23The Delian League and the Athenian Empire (478-431 BCE)

Formation of the Delian League

We can well imagine the Greeks' incredible feelings of pride and accomplishment in 478 B.C.E. after defeating the Persian Empire. The Athenians felt that they in particular had done more than their part with their army at Marathon and their navy at Salamis and Mycale. It was this incredible victory which gave them the self-confidence and drive to lead Greece in its political and cultural golden age for the next half century.

However, victory had been won at a heavy price. Fields, orchards, and vineyards lay devastated throughout much of Greece, and it would take decades for the vineyards and olive groves in particular to be restored. Athens itself was in ruins, being burned by the Persians in vengeance for the destruction of Sardis during the Ionian Revolt. Therefore, the Athenians immediately set to work to rebuild their city, and in particular its fortifications. The Spartans, probably through fear or jealousy of Athens' growing power, tried to convince the Athenians not to rebuild their walls. They said that if the Persians came back and recaptured Athens, they could use it as a fortified base against other Greeks. The Athenian leader, Themistocles, stalled the Spartans on the issue until his fellow Athenians had enough time to erect defensible fortifications. (This was later extended by what was known as the Long Walls to connect Athens to it port, Piraeus, so it could not be cut off from its fleet.) By the time Sparta realized what was happening, it was too late to do anything. One could already see bad relations starting to emerge between Athens and Sparta. In time, they would get much worse.

Since the Athenians and other Greeks could not assume that the Persians would not come back, they decided the best defense was a good offense, and formed an alliance known as the Delian League. The League's main goals were to liberate the Ionian Greeks from Persian rule and to safeguard the islands in the Aegean from further Persian aggression. The key to doing this was sea power, and that made Athens the natural leader, since it had by far the largest navy and also the incentive to strike back at Persia. At first, Sparta had been offered leadership in the league because of its military reputation. However, constant fear of Helot revolts made the Spartans reluctant to commit themselves overseas. Also, their king, Pausanias, had angered the other Greeks by showing that typical Spartan lust for gold. As a result, he was recalled, leaving Athens to lead the way.

The Persian navy, or what was left of it, was in no shape to halt the Greek advance after taking two serious beatings from the Greeks in the recent war. Ionia was stripped from the Great King's grasp, and the Persians were swept from the Aegean sea island by island. Within a few years, the Delian League controlled virtually all the Greeks in the islands and coastal regions of the Aegean.

From Delian League to Athenian Empire

At first each polis liberated from Persia was expected to join the league and contribute ships for the common navy. However, most of these states were so small that the construction and maintenance of even one ship was a heavy burden. Therefore, most of these states started paying money to Athens which used their combined contributions to build and man the League's navy. This triggered a feedback cycle where Athens came to have the only powerful navy in the Aegean, putting the other Greeks at its mercy. Athens could then use its navy to keep league members under control, forcing them to pay more money to maintain the fleet which kept them under control, and so on.

The changing nature of the league became apparent a decade after the defeat of the Persians when the island states of Naxos (469 B.C.) and Thasos (465 B.C) felt secure enough to try to pull out of the League. However, Athens and its navy immediately pushed them back in, claiming the Persian threat was still there. The Naxians and Thasians could do little about it since the only navy they had was the one they were paying Athens to build and man. And that was being used to keep them inthe League so they could keep paying Athens more money. The Delian League was turning into an Athenian Empire.

The cycle supporting Athens' grip on its empire also supported (and was itself reinforced by) another feedback loop that expanded and supported the Athenian democracy. It started with the empire needing the fleet as its main source of power and control. Likewise, the fleet needed the poor people of Athens to serve as its rowers. Since these people, even more than the middle class hoplites, were the mainstay of Athens' power, they gained political influence to go with their military importance, thus making Athens a much more broadly based democracy. The poor at Athens in turn needed the empire and its taxes to support their jobs in the fleet and their status in Athens. This fed back into the empire needing the navy, and so on.

The Athenian democracy likewise strongly enforced collection of league dues to maintain what in essence was now an "imperial democracy. Thus the navy was the critical connecting link between empire and democracy, holding the empire together on the one hand, while providing the basis for democratic power on the other. The Athenian democratic leader, Pericles, especially broadened Athenian democracy by providing pay for public offices so the poor could afford to participate in their polis' government.

Athens further tightened its hold on its empire by settling Athenian citizens in colonies ( cleruchies) on the lands of cities it suspected of disloyalty, making their subjects come to Athens to try certain cases in Athenian courts, thus supplying them with extra revenues, and moving the league treasury from its original home on the island of Delos to Athens where the Athenians claimed it would be safer from Persian aggression. Athens installed or supported democracies in its subject states, feeling they would be friendlier to Athenian policies since they owed their power to Athens. It also allowed the minting and use of only Athenian coins. This provided the empire with a stable and standard coinage as well as exposing everyone in the empire to Athenian propaganda every time they looked at a coin and saw the Athenian symbols of the owl and Athena.

When Pericles came to power in 460 B.C.E., the Athenians were trying to extend their power and influence in mainland Greece while also supporting a major revolt against the Persians in Egypt. However, Athens overextended itself in these ventures that, after initial successes, both failed miserably. Sparta led a coalition of Greeks to stop Athens' expansion in Greece, while the Persians trapped and destroyed a large Athenian fleet on the Nile by diverting the course of the river and leaving the Athenian ships stuck in the mud. As a result, Pericles abandoned Egypt to the Persians, left the rest of mainland Greece to the other Greeks, and restricted Athens' activity to consolidating its hold on its Aegean empire. By 445 BC, peace Persia and Sparta, recognizing each others' spheres of control allowed Athens to concentrate on more cultural pursuits which flourished in a number of areas.

In sculpture, the severe classical style succeeded the stiffer Archaic style after the Persian Wars. One key to this was the practice, known as contrapposto, of portraying a figure with its weight shifted more to one foot than the other, which, of course is how we normally stand. The body was also turned in a more naturalistic pose and the face was given a serene, but more realistic expression. The severe style was quite restrained and moderate compared to later developments, expressing the typical Greek belief in moderation in all things, whether in art, politics, or personal lifestyle. The overall result was a lifelike portrayal of the human body that seemed to declare the emergence of a much more self assured humanity along with Greek independence from older Near Eastern artistic forms. Other art forms showed similar energy and creativity.

In architecture, Pericles used the surplus from the league treasury for an ambitious building program, paid for with funds from the league treasury to adorn Athens' Acropolis. This also provided jobs for the poor, resulting in widespread popular support for Pericles' policies. Foremost among these buildings was the Parthenon. Constructed almost entirely of marble (even the roof) it is considered the pinnacle of Classical architecture with its perfectly measured proportions and simplicity. Ironically, there is hardly a straight line in the building. The architects, realizing perfectly straight lines would give the illusion of imperfection, created slight bulges in the floor and columns to make it look perfect. Although in ruins from an explosion in 1687 resulting from its use as a gunpowder magazine, the Parthenon still stands as a powerful, yet elegant testament to Athenian and Greek civilization in its golden age.

Another important, if less spectacular art form that flourished at this time was pottery. Around 530 B.C., the Greeks developed a new way of vase painting known as the red figure style. Instead of the earlier technique of painting black figures on a red background (known as the black figure style), potters put red figures on a black background with details painted in black or etched in with a needle. This technique, combined with the refined skills of the vase painters' working on such an awkward surface, gave Athenian pottery unsurpassed beauty and elegance, putting it in high demand throughout the Mediterranean.

In addition to its artistic value, Athenian pottery provides an invaluable record of nearly all aspects of Greek daily life, especially ones of which we would have little evidence otherwise, such as the lives of women, working conditions and techniques of various crafts, and social (including sexual) practices. Given these themes and the large number of surviving pieces, Greek pottery also reflected the more democratic nature of Greek society, since it was available to more people than had been true in earlier societies where high art was generally reserved for kings and nobles with the power and wealth to command the services of artisans.

Possibly the most creative expression of the Greek genius at this time was in the realm of tragic and comic drama, itself a uniquely Greek institution. While still sacred to the god of wine and revelry, Dionysus, Greek drama at this time developed into a vibrant art form that also formed a vital aspect of public discourse on contemporary problems facing the Athenian democracy. However, being part of a state supported religious festival still overtly concerned with religious or mythological themes, the tragedians' expressed their views indirectly by putting new twists on old myths. This kept discussion of the themes treated in the plays on a more remote and philosophical level. That, in turn, allowed the Athenians to reflect on moral issues that were relative to, if not directly about, current problems that they could then understand and deal with more effectively.

For example, Sophocles' Oedipus the King on one level was about flawed leadership which, no matter how well intentioned, could lead to disastrous results, in this case a plague afflicting Thebes for some mysterious reason. However, this play was produced soon after a devastating plague had swept through Athens and killed its leader, Pericles, who had led Athens into the Peloponnesian War. must have given the Athenians watching it reason to reflect on their own similar problems and what had caused them.

Greek comedy was best represented by Aristophanes, sometimes referred to as the Father of Comedy. Whereas Greek tragedians expressed their ideas with some restraint, comedy cut loose practically all restraints in its satirical attacks on contemporary policies, social practices, and politicians. Where else, in the midst of a desperate war, could one get away with staging such anti-war plays as Lysistrata, where the women of warring Athens and Sparta band together in a sex strike until the men come to their senses and end the war?

Such freedom of expression was also found in the realm of philosophy. We have seen how the most famous philosopher of the time, Socrates, "called philosophy down from the skies" to examine moral and ethical issues. In addition to Socrates, there arose a number of independent thinkers, referred to collectively as the Sophists, who were drawn to Athens' free and creative atmosphere. Inspired by the rapid advances in the arts, architecture, urban planning, and sciences, they believed human potential was virtually unlimited, One Sophist, Protagoras, said that, since the existence of the gods cannot be proven or disproven, Man is the measure of all things who determines what is real or not. This opened the floodgates to a whole variety of new ideas that also challenged traditional values. In his play, The Clouds, Aristophanes mercilessly satirized the Sophists as men who boasted they could argue either side of an argument and make it seem right. This belief that there is no real basis for truth would especially affect a younger generation of Athenians. Some of them, ungrounded in any sense of values, would mistake cleverness for wisdom and lead Athens down the road to ruin.

It is incredible to think that Western Civilization is firmly rooted in this short, but intense outpouring of creative energy from a single city-state with perhaps a total of 40,000 citizens. However, Athens' golden age would be short-lived as growing tensions would trigger a series of wars that would end the age of the polis.

FC23AThe Persian Wars (480-478 BCE)

In winter, on your soft couch by the fire, full of food, drinking sweet wine and cracking nuts, say this to the chance traveler at your door: 'What is your name, my good friend? Where do you live? How many years can you number? How old were you when the Persians came...?— Xenophanes

The Persian Wars (510-478 B.C.E.)

To the Greeks, there was one defining event in their history: the Persian Wars. Even today, we see a good deal of truth in this assessment, for the Greek victory in the Persian Wars triggered the building of the Athenian navy, which led to the Athenian Empire, the expansion of the concept of democracy, and the means to develop Greek civilization to its height.

Two main factors led to the Persian Wars. First, there was Persian expansion into Western Asia Minor, (bringing Ionian Greeks under their control) and into Thrace on the European side of the Aegean in search of gold. Second, Solon's reforms and Peisistratus’ seizing control of Sigeum had made Athens especially sensitive to any threats to its grain route from the Black Sea. Further complicating this was the fact that several Athenian nobles held lands in the North Aegean. The spark igniting this into war with Persian was a revolt of the Ionian Greeks.

The Ionian Revolt (5l0-494 B.C.E.)

The Ionian Greeks had peacefully submitted to Persian rule and lived under Persian appointed Greek tyrants since the time of Cyrus the Great. Then in 5l0 B.C.E., the Ionian Greeks raised the standard of revolt and drove their tyrants out. Realizing they needed help against the mighty Great King, Darius, they appealed to their cousins across the Aegean for aid. Sparta, ever wary of a Helot revolt, refused to help. However, Athens and another city-state, Eretria, did send ships and troops who joined the Ionians, marched inland, and burned the provincial capital, Sardis, to the ground. After a Persian force defeated the Greeks as they were returning from Sardis, the Ionian Greeks decided to stake everything on a naval battle at Lade (494 B.C.E.). Unfortunately, the combination of disunity in their ranks and Persian promises of leniency caused the naval squadron of one polis after another to defect to the Persians and Ionian resistance to collapse. Miletus, leader of the revolt was sacked and the rest of Ionia fell back under Persian sway.

Athens alone (494-490 B.C.E.)

The Athenians and Eretrians had eluded the Ionian disaster, but not Darius' notice. After finding out who the Athenians were, Darius supposedly appointed a slave to remind him of them daily until he had punished them. In 492 B.C.E., an expedition set sail, but much of it was shipwrecked off the coast of Thrace and the rest of it was forced to return home. Nothing daunted, Darius prepared another invasion force which set out in 490 B.C.E.. Persian ambassadors had preceded the army to demand earth and water as signs of submission from all the Greeks. Most gave in rather than face the might of the Great King. However, the Athenians supposedly threw them into a pit and told them to take as much earth as they wanted, while the Spartans, equally defiant, gave them their water by throwing them into a well.

Later that year, a Persian force of some 20,000 men landed at Marathon in Attica. Unfortunately, the Spartans, being as superstitious as they were defiant, could not march before the end of a festival on the full moon. Thus the Athenians were left to face the might of Persia all alone, or nearly alone, since the tiny city-state of Plataea sent its army of 1000 men to stand bravely by Athens. The Greeks still faced an army twice as numerous as their own and reputedly invincible in battle. Therefore, they did the last thing the lightly clad and overconfident Persians expected: they charged. The Persians hardly had time to unleash a volley of arrows before the Greeks were upon them. The shock of this human tank of heavily armored Greek hoplites crashing into their lines sent them reeling back and scurrying for their ships. The Persian fleet made a quick dash for defenseless Athens, only to find the Athenians had doubled back to meet them. Having lost their stomach for anymore fighting, they sailed for home.

Xerxes' invasion (480-478 B.C.E.)