RomeUnit 4: Rome

FC26The Impact of Geography on Ancient Italy

Introduction

When we think of the Greeks, we think of a bold, intelligent people who gave us so much in the way of art, architecture, drama, democracy, science, and math. When we think of the Romans, we think of empire builders. They were a more down to earth people who may have done little that was original compared to what the Greeks did. But they built and maintained an empire that peacefully embraced the entire Mediterranean Sea for some two centuries, an accomplishment unparalleled in history. The Romans also spread civilization into Western Europe. In that sense, they were the bridge between the older cultures of the ancient Near East and our culture, known as Western Civilization.

There is probably no story that better illustrates what the early Romans were all about than that of the founding of Rome by the twin brothers, Romulus and Remus. According to this legend, there was disagreement over where to found the city. When omens from the gods failed to settle the dispute, Romulus just started digging the pomerium (sacred boundary) of Rome where he thought the gods wanted it. Remus mockingly leaped over this trench and Romulus killed him, declaring that such a fate should befall all who dared to breach the walls of Rome. The story of Romulus and Remus shows that the Roman sense of honor, duty, and loyalty to Rome ran even deeper than family and kinship ties. Other Roman legends also had this theme of honor and duty running through them: the story of Horatius, who single-handedly defended a bridge against invading Etruscans in order to buy his city time to prepare a defense; the consul Brutus who had his own sons executed for plotting treason against Rome; and Lucretia, who committed suicide rather than live with dishonor to herself and Rome. Such stories idealize the Roman character, but also raise the question of what factors shaped it and pushed Rome to greatness. And, of course, the first place to look is the environment surrounding Rome and its people.

Geopolitics

At the time of its founding around 750 B.C.E., there was little to hint that Rome and Italy would be the center of the greatest empire in antiquity. Italy did have good soil along with some resources and good harbors in the South. These features attracted Greek colonists whose culture would exercise an immense influence on Roman civilization. Also, Italy's soil tended to make its people farmers rather than artisans and merchants.

These factors, in particular the close ties to the soil, largely molded the Romans' personality as a people. While it is dangerous to stereotype a whole people's character, there are certain values and circumstances that any people as a whole share which helps define how they think and act. The quick-witted Greeks, whom the sea and lack of resources forced into becoming clever and resourceful traders, looked upon the agricultural Romans as slow and dull. But there were several characteristics that would help the Romans become great empire builders. First of all, being farmers bred a certain ability and willingness to persevere through hardships. Nothing shows this better than Rome's dogged perseverance and eventual victories in its first two wars against Carthage, wars which dragged on for 23 and 17 years respectively. Agriculture tended to make the Romans somewhat more conservative and wary of change. They were also a tightly knit society, more willing to submit to the rule of law than the quarrelsome Greeks ever were. This Roman discipline produced magnificent soldiers and the most efficient and effective armies in the ancient world. It also produced an intense desire for the rule of law that made the Romans possibly the greatest lawgivers in history. Many Western European countries today base their law codes directly on earlier Roman law codes.

One other characteristic marked the Romans for greatness: a willingness to adapt other peoples' ideas for their own purposes. All people borrow ideas, but few have been so adept at it as the Romans. Their art, architecture, technology, city planning, and military tactics all owed a great deal to other peoples' influences. Indeed, there was little that the Romans did that was totally original. But the sum total of what they did was uniquely Roman and marked them out as one of the most remarkable peoples in history.

Italy's topography also had an impact. The Alps to the North provided some protection, although occasionally invaders, such as the Gauls and Carthaginians, did break in. Another mountain range, the Apennines, ran along the length of the peninsula much like a backbone. While this had the effect of dividing Italy into various city-states, it was not nearly to the extent that Greece was broken up by its mountains. These two factors, plus the Roman character, allowed Rome to unite Italy relatively free from outside interference

Finally, Italy's location favored it in two ways. It had a strategic position that divided the Mediterranean into western and eastern halves. Also, it was far enough away from the older civilizations of antiquity to allow it to develop on its own without too much outside interference. Therefore, once Italy was unified, its geographic position allowed Rome to unite the Mediterranean under its rule.

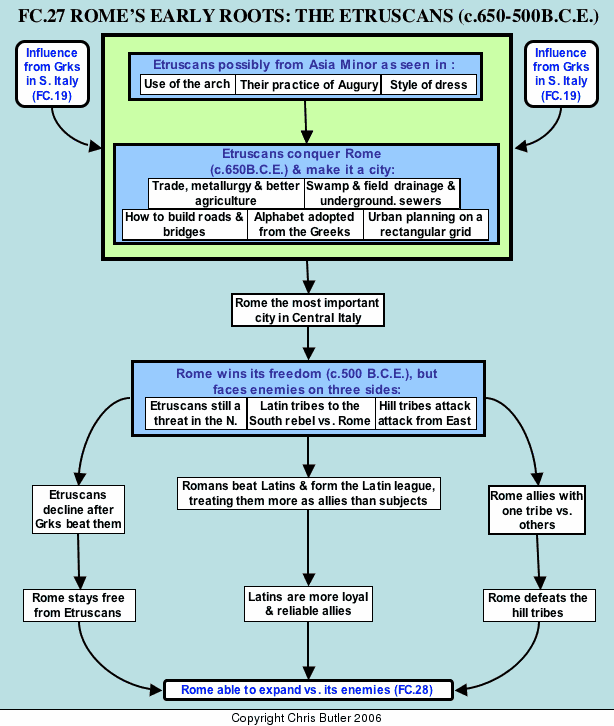

FC27The Etruscans & their influence on Rome (c.800-500 BCE)

Although there is evidence in Roman myth and archaeology of various shepherd villages on Rome's seven hills, the city's history really started with the Etruscans. The origins of this mysterious people are obscure. Some ancient sources liked to trace them back to Asia Minor because of their religious practices such as augury (reading flights of birds to tell the future), style of dress (in particular their pointed shoes which resembled those of the Hittites), their use of the arch in architecture, and their obscure language. However, even to this day, the origins of the Etruscans remain a mystery.

The Etruscans were organized into a loose confederation of city-states to the north of Rome. Around 650 B.C.E., they took control of the site of Rome, with its defensible hills and location on a ford of the Tiber River. They did a number of things to transform this crude collection of shepherds' huts into a true city. The Etruscans introduced rectangular urban planning. They drained the surrounding marshes and built underground sewers. They built public works using the arch and vault, and laid out roads and bridges. They promoted trade, the development of metallurgy, and better agriculture in and around Rome. The Etruscans, being heavily influenced by the Greeks, also introduced the Greek alphabet, thus introducing Greek influence into Roman culture. In fact, Roman nobles during this period would send their sons to be educated in Etruscan schools much as they would later send their sons to Greece for an education. The dark and gloomy Etruscan religion, in particular the custom of gladiators fighting to the death at the funeral of a king or noble, also had a significant impact on Rome. This is seen much later in Christian images of demons that seem to be modeled after Etruscan demons. Overall, the Romans owed a great deal to the Etruscans. The genius they would show for urban planning, road and bridge building, and civil engineering projects such as public aqueducts and baths, was a direct result of the legacy left by the Etruscans.

By 500 B.C.E., the Etruscans had also made Rome most important city in the central Italian region of Latium. This enabled it to dominate its close neighbors, the Latins and finally encouraged it to rebel against its masters. Two other factors aided the Romans in their struggle. First of all, Rome's hills and fortifications helped defend it against attack. Second, the Etruscans' loose organization into a confederacy of independent city-states made them vulnerable to attack by the Greeks in South Italy who were their rivals for trade and sea power.The Greeks won a decisive victory, which allowed Rome to successfully shake off Etruscan rule around 500 B.C.E. or later. However, Etruscan aggression remained a serious threat for the better part of a century. Therefore, it was not until around 400 B.C.E. that Rome was secure enough to embark upon its own path of conquest.

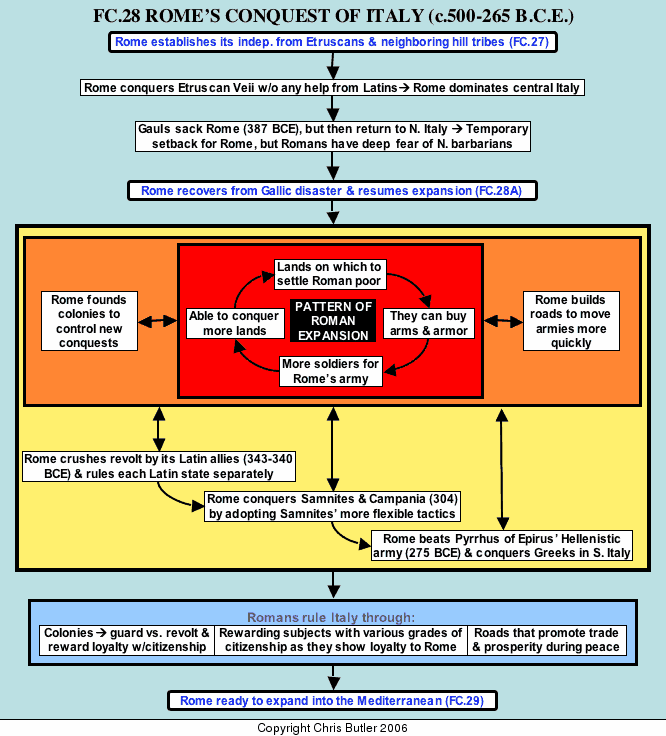

FC28The Roman conquest of Italy (c.500-265 BCE)

Rome's pattern of conquest

Except for the brief interruption of the Gallic disaster, Roman expansion in Italy was almost uninterrupted in the period 400-265 B.C.E. Among its first victims was the Etruscan city, Veii, which Rome attacked on its own without any help from its Latin allies. Therefore, when Veii fell, Rome gained a large amount of land for itself without having to share it with the Latins. It gave much of this land to poor Roman citizens, which set into motion a recurring pattern that would eventually help Rome conquer Italy. Since more Romans had land, they could now afford the arms and armor to serve in the army. This gave Rome a larger army, which meant it could conquer more land, distribute it to more citizens, further increase its army, and so on.

Two other Roman practices came out of this cycle and led back into it to help Rome in its path of conquest. One was the practice of founding colonies to gain and secure their hold on a region. The other was the building of roads to help Roman armies move more quickly and easily than their enemies to threatened areas.

After the fall of Veii, Rome would sweep from one conquest to another, first crushing a revolt by its Latin allies, next conquering the Samnites and Campania in two hard-fought wars, and finally defeating the Hellenistic army of Pyrrhus of Epirus to bring the Greeks in Southern Italy under control. And with each conquest, more Romans would get land, buy arms and armor, and increase Rome's army, conquests, etc.

Rome's campaigns of conquest (387-265 B.C.E.)

Rome's recovery from the Gallic invasion was swift. It quickly put down a revolt of the Latin allies and then replaced the Latin League with separate treaties between Rome and each Latin state, thus tying each city to Rome alone.

Rome's victory now got it involved in affairs in Campania. When southern hill tribes, known as Samnites, started threatening the rich cities of Campania, they looked to Rome for help. This touched off the Second Samnite War (326-304 B.C.E.). The Romans quickly ran into serious problems fighting the Samnites in the hills. Up to this point they had used the Greek style phalanx as their main tactical unit. This was ill suited to fighting in mountain passes. An entire Roman army was even captured in a pass known as the Caudine Forks. The Roman, being ever adaptable, copied their Samnite enemies who used more open and flexible formations with soldiers equipped with throwing javelins, swords, and lighter armor. These formations, called maniples, were arranged in a checkerboard fashion that allowed the Romans to advance fresh troops into a battle and withdraw tired ones from it. The new Roman legions might bend, but they rarely broke. Not only did they win the Samnite wars and Italy for Rome, but, with a few modifications, they would eventually conquer the entire Mediterranean.

The Second Samnite War was a long, hard fought affair that saw Rome initiate two other policies: road building and colonies. In 3l2 B.C.E., the Romans built the first of their military roads, the Appian Way, to move troops quickly in times of war. However, the Appian Way and other such roads would also be highways of trade and commerce in peacetime. Eventually, there would be 5l,000 miles of paved roads linking different parts of the Roman Empire together. Rome also founded colonies to cut Samnite supply lines and communications and established firm Roman control in the area.

Because of their military reforms, roads, and colonies, the Romans finally defeated the Samnites in 304 B.C.E. They were lenient with their defeated enemies, but this allowed the Samnites to start a third war (298-290 B.C.E.). However, the Roman system of maniples, roads, and military colonies on their enemies' borders gradually strangled the Samnites into submission once again.

Except for Cisalpine Gaul, only the Greeks in the very south were now free of Roman control. Growing increasingly nervous about Rome's intentions, the most powerful of these cities, Tarentum, went to war with Rome in 280 B.C.E. Tarentum had great wealth, but little fighting spirit. Therefore, it had the unusual habit of hiring foreign kings to fight its wars. In this case, it called in Pyrrhus, a cousin of Alexander the Great and ruler of the kingdom of Epirus, north of Greece. For the first time, the Romans were up against a military system more sophisticated than their own, using the dreaded Macedonian phalanx and war elephants. The more flexible maniples fought bravely on the plains of Heraclea and Ausculum, but were beaten. However, Pyrrhus' victories were so costly compared to what he gained that even today we refer to such victories as "pyrrhic". In the face of such defeats Roman perseverance shone forth, the Senate refusing to make peace until every last Macedonian had left Italian soil. In 275 B.C.E., the Romans beat the Macedonian phalanx by luring it onto hilly or broken ground. Pyrrhus beat a hasty retreat back to Epirus, and Italy now belonged to Rome.

Conquering a region is one thing. Ruling it is another. And it was here that the Romans showed their true greatness. Instead of ruling like tyrants, they offered various grades of Roman citizenship and the chance to share the benefits of Roman rule with the Italians in return for their loyalty. Newly conquered cities were made allies that had trade and marriage privileges with Romans. As a city gradually proved its loyalty to Rome, it would receive the status of partial, or Latin, citizenship. Eventually, a city proving its loyalty over a long period of time would be granted full Roman citizenship. All of Rome's subjects were expected to supply troops for war and give up their independent foreign policies. However, Rome did let them keep their local governments and customs, but they tended to resemble those of the Romans more and more with the passage of time. Rome also kept building roads and founding colonies. Colonies with Latin citizenship were especially popular, since they were a bit more independent than full Roman colonies, while still providing Rome with troops.

The value of Rome's system for governing Italy should be obvious. Instead of constantly worrying about rebellions, it had a reliable source of loyal manpower and resources to help increase its power. The greatest test of this was when Hannibal tried to conquer Italy, thinking the Italians would flock to his standard against the Roman tyrant. Instead, most of Italy, especially the parts under Roman rule the longest, stood fast by Rome, despite the fact that Hannibal's army was in Italy for sixteen years. The Romans would continue this policy of offering citizenship to their subjects. In fact, in 2l2 A.D., the Roman emperor, Caracalla, completed this process by offering Roman citizenship to all freeborn men in the empire.

By 265 B.C.E., Rome had a strong stable government and Italy firmly under its control, secured by the lure of citizenship, a growing network of military roads and colonies, and probably the best-trained and most efficient army of its day. Given such a large, well organized, and energetic power, it should come as no surprise that Rome was ready for further expansion. Across the narrow strait of water to the south beckoned Sicily. Expansion there would mean war with a great naval power, Carthage, and the start of the road to empire.

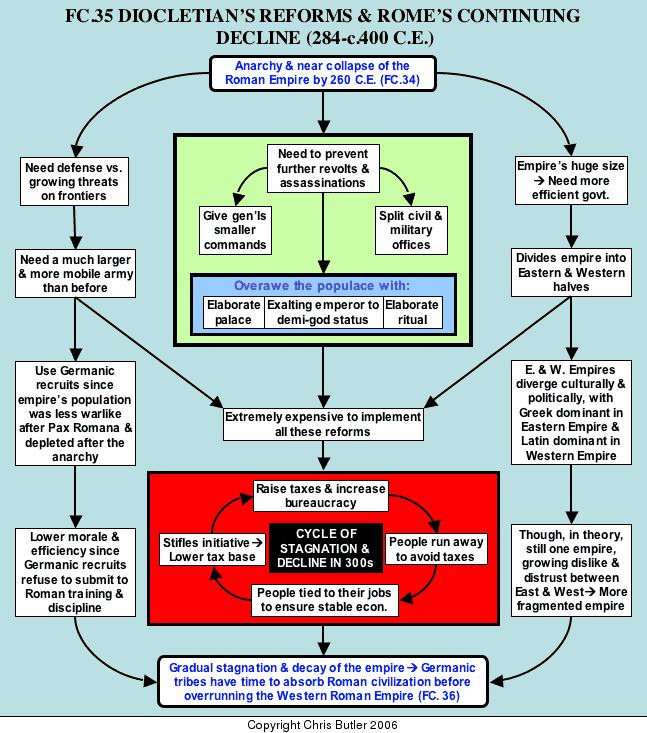

FC28ARome's Wars of Conquest in Italy (366-265 B.C.E.)

Reading in Development

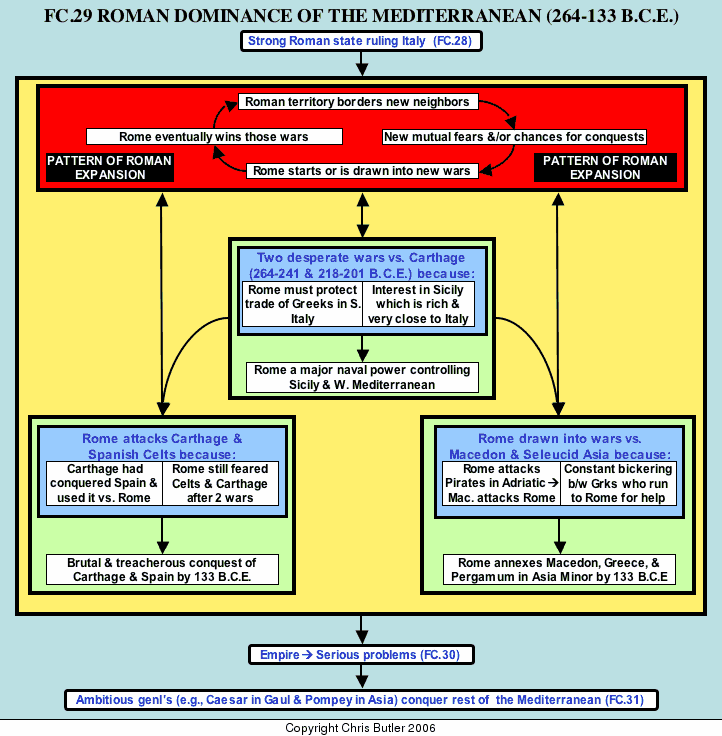

FC29The Roman conquest of the Mediterranean (264-133 BCE)

Just as Rome got caught up in a cycle of expansion that led to the conquest of Italy, it experienced another such cycle that led to their dominance of the Mediterranean. In this case, what triggered the pattern was the mere fact that each new conquest brought Rome into contact with a new set of neighbors. This would lead to new opportunities for conquest, but also mutual fears and suspicions on each side. Either way, Rome would get drawn into a new set of wars, which it would eventually win with new conquests. This, of course, would present Rome with some more new neighbors and the pattern would repeat itself until Rome had conquered the Mediterranean.

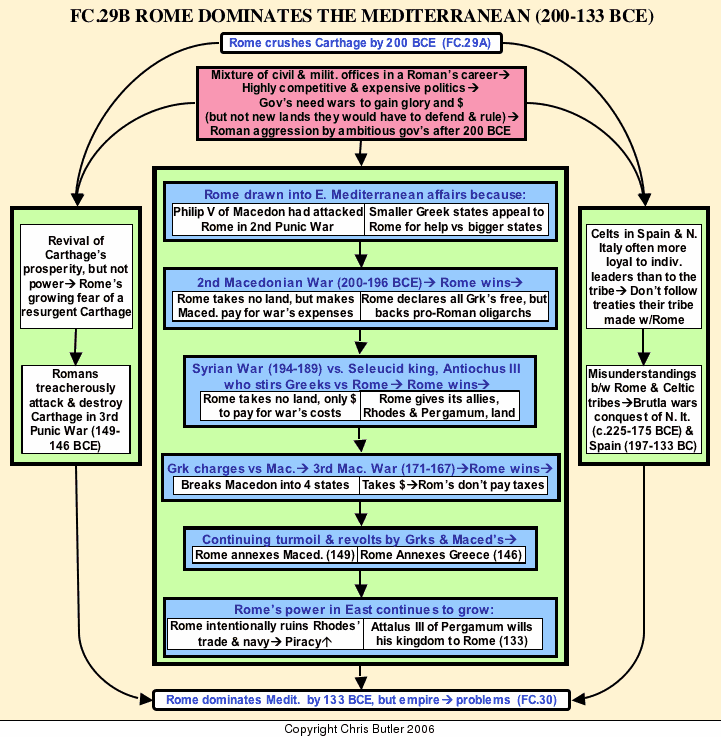

The first phase of this expansion involved Rome in two desperate wars against Carthage (264-241 & 218-201 B.C.E.). Initially, this struggle was over Sicily, since it was rich, very close to Italy, and Rome had to protect the trade of its Greek subjects in Southern Italy against Carthaginian encroachment. Rome's victory in these wars made it a major naval power controlling Sicily and dominating the Western Mediterranean. Feeding back into the cycle of expansion, this also led to contact and conflict with new peoples in the Eastern and Western Mediterranean.

In the West, Rome got involved in wars with Carthage and the Celts in Spain, both of whom Rome feared from previous wars. Therefore, Rome conquered and destroyed Carthage in 146 B.C.E. and the Spanish Celts by 133 B.C.E., both of them in rather brutal and treacherous fashion.

In the East, Rome was more reluctantly drawn into wars against Antigonid Macedon and Seleucid Asia by two main factors. For one thing, Macedon, suspicious of Rome since it had crushed the Illyrian pirates close to Macedon's shores, had declared war on Rome during its darkest days of the Second Punic War. While nothing much came of this First Macedonian War (215-205 B.C.E.), Rome was naturally suspicious of Macedon. Feeding this suspicion was the second factor, various Greek states running to Rome for protection, at first against Macedon and the Seleucids, and later against each other. As Rome was drawn increasingly into affairs in the East, its frustrations grew until it annexed Macedon (149 B.C.E.), Greece (146 B.C.E.) and Pergamum in Asia Minor, which was willed to Rome by its king in 133 B.C.E.

By 133 B.C.E., Rome was the dominant power in the Mediterranean. Unfortunately, having an empire would put stresses and strains on Roman society, including the creation of ambitious generals looking for new opportunities for conquest, plunder, and glory. Therefore, the Roman tide of conquest continued after 133 B.C.E. In the West, an ambitious general named Julius Caesar would push the barbarian threat even further north by conquering the Celts in Gaul. Eventually, the rest of North Africa would fall under Roman rule to round out control of the Western Mediterranean. Meanwhile, in the East, Mithridates of Pontus attacked Rome's provinces in Asia Minor. Rome won both of these Mithridatic wars, and its generals, most notably Pompey, progressively annexed the rest of Asia Minor, Syria, Palestine, and Egypt. Thus by the early Christian era, the entire Mediterranean was firmly under Roman rule.

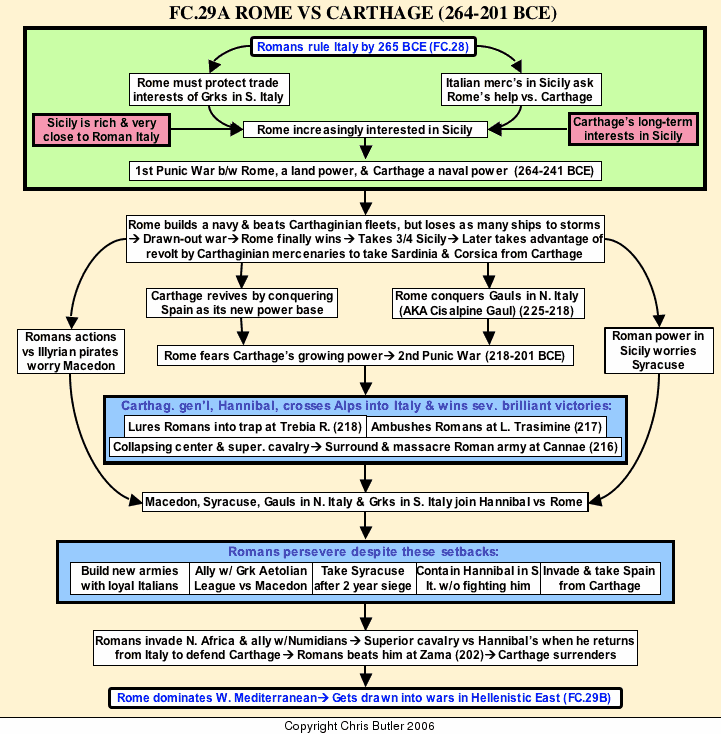

FC29ARome versus Carthage: The Punic wars (264-201 BCE)

The First Punic War(264-241 B.C.E.)

Rome's first overseas wars were against Carthage on the coast of North Africa, the largest, most prosperous, and aggressive of the Phoenician cities. The prize they fought for was the island of Sicily, which for centuries had been a constant battleground between Carthage and various Greek colonies. Neither side had won a decisive victory, and when Rome got involved, the island remained divided between Carthage in the western end of the island and the Greeks in the east. Rome's relations with Carthage down to 264 B.C.E. had been friendly. The two powers had even allied around 500 B.C.E. against the Etruscans. By this treaty Rome recognized the Mediterranean as Carthage's sphere of influence, and Carthage even claimed a Roman could not wash his hands in the sea without its permission. As long as Rome was just a land power preoccupied with conquering Italy, this arrangement was fine. However, in 264 B.C.E., with Italy firmly under control, the Romans first got involved in Sicilian affairs.

There were several reasons for this war. For one thing, both Rome and Carthage saw Sicily as a natural extension of their respective territories. Similarly, the Greeks in Southern Italy felt Sicilian trade and resources were rightfully theirs to exploit and probably put pressure on Rome to protect their interests there. The immediate cause of this war was a group of Italian mercenaries called the Mamertines ("Sons of Mars") who had seized the strategic port of Messana just across from Italy. The Romans, seeing the port as vital to the security of Italy, helped the Mamertines when Carthage moved to take the city, and this led to war.

The First Punic War (264-24l B.C.E.)resembled the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta, in that each conflict pitted a land power against a sea power where one side would have to attack the other side's strength. In each case, it was the land power that built a navy. Roman experience with a navy up till now had been limited, which seems surprising considering how much coastline Italy had to defend. However, probably with the help of Greek shipwrights in the south, the Romans built a fleet with which to challenge Carthage.

The Romans realized they could not match Carthage's centuries of experience in naval warfare. As a result, they adapted a heavy boarding bridge, known as the corvus ("crow"), from the Greeks. Any Carthaginian ship daring to get close enough would find this bridge slamming down on its deck and Roman soldiers pouring over to capture it. In essence, the Romans were turning a sea battle into a land battle. As ridiculous as it seemed, it worked. Time and again, Roman fleets crushed Carthaginian fleets and were steadily sweeping Carthage from the seas. However, Rome had one very powerful enemy that evened things out: Mother Nature. It seemed that for every Carthaginian fleet the Romans destroyed, a storm would rise up to demolish a Roman fleet. Thousands of lives were lost on each side with neither Rome nor Carthage making any headway or willing to quit.

For twenty years the war dragged on, bleeding each side white. Finally, in 24l B.C.E., the Romans mounted one last supreme effort to build a fleet, this time without the heavy corvus to weigh down the ships. As luck would have it, they caught the last Carthaginian fleet loaded down with supplies and destroyed or captured most of it. Carthage had had enough and sued for peace. Rome took 3200 talents (2ll,200 pounds) of silver and three- fourths of Sicily, leaving its ally Syracuse with the other quarter. Sicily became Rome's first province, having little prospect of Roman citizenship since, in Roman eyes, the Sicilians were too different to be able to share in the benefits of Roman rule.

Between the wars

Rome was quite active in the years after the First Punic War. To the north, it conquered the Gauls in Northern Italy, known as Cisalpine Gaul ("Gaul this side of the Alps"), thus extending Roman rule all the way to the Alps. To the east, the Romans crushed the Illyrian pirates operating in the Adriatic Sea. Although this was done mainly to protect the shipping of the Greeks in Southern Italy, the Macedonian king, Philip V, viewed it as an act of aggression by Rome in his home waters. Another power getting concerned about Roman power was Syracuse, which found itself hemmed in by Roman rule in most of Sicily.

Then there was Carthage. In 238 B.C.E., when Carthage was still weakened from the First Punic War, Rome seized Sardinia and Corsica, two islands off the west coast of Italy that it saw as a threat if they remained in Carthaginian hands. However, the Carthaginians were a resilient people who were not about to accept Rome's victory for long. Soon after the war, Carthage's most capable general, Hamilcar Barca, set off for Spain to carve out a new empire for his city. Over the next twenty years, Hamilcar, his son-in-law Hasdrubal, and Hamilcar's own son Hannibal, brought most of Spain, with its plentiful silver and mercenaries, under Carthaginian rule.

As Carthaginian power revived in the West, Rome became increasingly nervous. Finally, war broke out when Hannibal attacked the Spanish city of Saguntum, which was an ally of Rome. The Second Punic War (2l8-20l B.C.E.) would be an even more desperate struggle than the first war with Carthage.

The Second Punic War (218-201 BCE)

The Carthaginian general, Hannibal, was a brilliant commander who figured the best way to beat Rome was to invade Italy so Rome's subjects would desert to his side. Since the Roman navy was too strong for him to risk an invasion by sea, Hannibal took the only remaining route, over the Alps. This march, which involved taking some 40,000 men and 37 war elephants through hostile Gallic territory and treacherous mountain passes, certainly ranks as one of Hannibal's most remarkable achievements.

Only some 25,000 men and one elephant survived this march, and the Romans immediately moved north to finish off Hannibal's sick and exhausted army. However, it was Hannibal who, over the next two years, dazzled the Romans with an array of tricks and strategies that trapped and destroyed one army after another. The most devastating of these battles, Cannae (216 B.C.E.), was a masterpiece of strategy using a collapsing center to draw the Romans in and then envelop their flanks. The ensuing slaughter cost Rome 35,000 men. Cannae unleashed a virtual avalanche of problems on Rome as other states, nervous about Roman power, flocked to Hannibal's standard. Syracuse joined the Carthaginian side. Philip V of Macedon, fearing Roman encroachment in the Adriatic, also allied with Hannibal against Rome. In Italy, both the Gauls in the north and the Greeks in the south defected to Carthage's side. However, Hannibal was disappointed that the overwhelming revolt against Rome never took place. Instead, the central core of Italy stood fast by Rome, producing more armies as Rome pursued new strategies.

In their darkest hour after Cannae, The Romans displayed incredible spirit and determination. They defiantly refused to ransom soldiers who had surrendered at Cannae and forbade any talk of peace or even public mourning that might lower morale. They quickly put Syracuse under siege, found allies in Greece to keep Philip V of Macedon too busy to be able to help Hannibal in Italy, and raised armies to invade Spain and deprive Carthage of its main resource base. In Italy, Roman armies gradually pushed Hannibal into the South, while being careful not to test his wizardry in open battle. Instead, the Romans, using superior manpower and resources, gradually wore Hannibal down while chipping away at his supports elsewhere.

It was a slow exhausting strategy that required remarkable perseverance. But in time it bore fruit. Macedon was neutralized. Syracuse fell after an epic two-year siege. Spain was gradually stripped from Carthage's grasp. And two relief armies sent to Hannibal's aid were destroyed in the north before reaching him. Hannibal managed to hang on tenaciously in southern Italy as he saw even his Italian allies melting away under growing Roman pressure. Finally, the Romans mounted an invasion of Africa that forced Hannibal to return home. At Zama, the brilliant Roman general, Scipio, used Hannibal's tactics against the old master to crush his army and bring Carthage to its knees. Rome deprived Carthage of Spain, most of North Africa, 10,000 talents (660,000 pounds) of silver, all its war elephants and all but ten warships. Its African lands went to Rome's ally Numidia, while Spain remained to be conquered. The quarter of Sicily around Syracuse also fell to Rome. Rome had arrived as the dominant power in the West.

FC29BFurther expansion of Roman Power (200-133 BCE)

Like it or not, (and many Romans did not), Rome was now a Mediterranean power. This involved it in an ever-widening circle of affairs that it found itself less and less able to avoid contact with. As a result, the next seventy years saw Rome's power and influence growing throughout both the Western and Eastern Mediterranean.

Much of Rome’s expansion was tied in with the nature of Roman politics, which were both highly competitive and expensive. A Roman’s public career consisted of rising through a tight mixture of military and civil offices, with success in war being the most important factor. Military victories brought a Roman glory, status (which heavily affected his success in politics), and money (which helped him pay for his political career). Therefore, after 200 B.C.E., when Romans found themselves outside of Italy and far from the control of the Roman Senate, they were often tempted to attack foreign peoples to gain the money and glory needed to continue their careers back home. Although Romans might be eager to win fame and riches, they were generally reluctant to conquer new lands, since that would involve the trouble and expense of actually ruling those new provinces. Therefore, while Rome’s power was clearly dominant in the Mediterranean by 133 B.C.E., a map of the Mediterranean at that time would hardly reflect that power as the Romans during this period often passed up opportunities for conquest.

Despite the harsh treaty imposed in 20l B.C.E., Carthage bounced back to regain its prosperity, although not its power. This still worried some Romans who recalled the trials and tribulations of two previous wars with Carthage. One of these Romans, Cato the Elder, was so fearful of Carthage that no matter what the topic of his speech in the Senate, he always ended it with "Carthage must be destroyed." Finally, in 149 B.C.E., the Romans listened to Cato, and tricked the Carthaginians into disarming before demanding the complete destruction of their city. This was too much, and the Carthaginians somehow managed to rearm and put up a furious defense. The resulting siege of Carthage, known as the Third Punic War, lasted three years (149-146 B.C.E.). In the end, the Romans stormed Carthage's walls and leveled it to the ground. This destroyed Rome's most dangerous enemy, but also put a serious blotch on its record for fair play. However, Rome still left most of North Africa to Numidia rather than taking it for itself, showing it was probably motivated against Carthage more by fear than greed.

Rome’ wars with Celtic tribes in Cisalpine Gaul (Northern Italy) and Spain were also brutal. However, it was largely cultural differences, especially over their respective concepts of the state,that triggered disastrous misunderstandings between Rome and the Celts. The Romans’ saw the state as being the totality of the people in a society, as expressed in their motto “The Senate and the Roman People” (SPQR). Therefore, any treaty signed by legal representatives of the Roman state was considered binding on all Romans. On the other hand, Celtic peoples, especially those in Spain, were much more loosely organized into tribes. And even if a tribe’s leaders signed a treaty with Rome, other members of the tribe, especially those with their own war bands personally loyal to them, might not agree with it and continue fighting. In the Romans’ eyes, this was a clear violation of the treaty and merited retaliation. Unfortunately, since the Romans could not tell who was guilty or innocent, they often struck against tribesmen who were abiding by the treaty, seeing them all as equally guilty since they were all bound by the same treaty. Naturally, the wrongly accused Celts would strike back, confirming Roman opinions of them and triggering a cycle of hatred and violence that was very hard to break.

Therefore, the Roman conquests of Cisalpine Gaul and Spain were especially brutal, involving ambushes, massacres, and broken treaties by both sides. It took the Romans half a century to pacify Cisalpine Gaul and and nearly seventy years to conquer most of Spain. The final conquest of north-western Spain would not be finished until 19 B.C.E.

Roman involvement in the East was more reluctant, especially after two exhausting wars with Carthage. However, Rome had already been involved there in suppressing pirates in Illyria and in the war that Macedon had declared on it during the struggle with Hannibal. To some powers, such as Macedon and the Seleucid kingdom, the rising power of Rome seemed a threat. But to others, such as Rhodes and Pergamum, it seemed like salvation from aggression by Macedon and Seleucid Asia. When they appealed to Rome for help, they portrayed their enemies as a threat to Rome as well, pointing out how Philip V had attacked Rome in the midst of its life and death struggle against Hannibal.

Reluctantly, the Roman people agreed to declare what is known as the Second Macedonian War (20l-196 B.C.E.). After a slow start, the Romans finally met the Macedonian phalanx at Cynoscephelae. As in the war against Pyrrhus a century before, the legions' flexibility proved decisively superior to the phalanx's rigidness, and Rome won the war. Rome's settlement shows its reluctance to get involved in the East beyond securing Italy's flanks. Rome took no land and only 1000 talents (66,000 pounds) of silver to cover the costs of the war. Either as a generous move or in order to further weaken Macedon, Rome declared all Greeks free from foreign intervention, and by 194 B.C.E. its own troops were gone from Greek and Macedonian soil.

However, Rome's troubles with Macedon and the Seleucid Empire were far from over. The Greeks, as always, kept squabbling with each other. This opened the way for the Seleucid king, Antiochus III, to invade Greece. Appeals from various Greeks and the advance of Antiochus' army into Greece led to the Syrian War (192-189 B.C.E.). The Romans turned Antiochus' defenses at Thermopylae Pass, drove him from Greece, and tracked him into Asia Minor. For the first time, Roman troops crossed into Asia. After crushing Antiochus' phalanx and army at Magnesia, Rome made peace, claiming no land for itself, but taking 15,000 talents of silver to pay for the war and giving land to its ally, Pergamum.

Of course, Rome's involvement could not end that easily. More squabbling between Macedonians and Greeks led to the Third Macedonian War (17l-167 B.C.E.) with the same basic result. Again, the legions tore up the Macedonian phalanx. And again, Rome took no land, but it did break Macedon into four separate and weak states. By now, Roman patience was at an end. A revolt in 149 B.C.E. led to Rome finally annexing Macedon as a province. And more Greek quarreling led to war, the sack of Corinth, and turning Greece into a Roman province in 146 B.C.E.

In 133 B.C.E., the king of Pergamum died and willed his kingdom to Rome, probably thinking annexation was only a matter of time. Two other kingdoms, Bithynia and Egypt, would also be willed to Rome in the next half-century, showing the dominance of Rome in the Mediterranean. Even those areas not directly under Roman rule increasingly felt its presence and would eventually fall. However, as remarkable as the rise of Roman power was, it also brought serious problems that would plunge Rome into bloody civil strife.

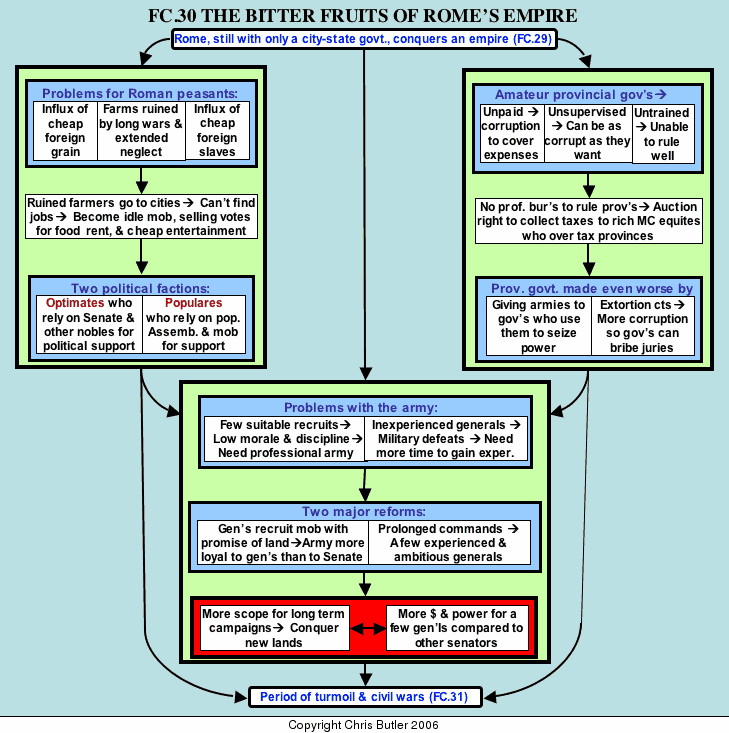

FC30The problems of Empire

Success often carries with it the seeds of its own destruction, and that was certainly the case with the Roman republic by the late second century B.C.E. "Superpower" status wrought far-reaching changes affecting all levels of Roman society. Unfortunately, the conservative Romans had great difficulty adapting to such rapid changes. The result was a century of political and social turmoil during which Rome kept trying to patch up these new problems with the same old solutions. Fortunately for Rome, it was still dynamic and energetic enough to survive and even expand during this period of social decay and political and military turbulence. Rome faced serious problems in three areas: the fate of its peasants, the government of its provinces, and its army.

For Rome's peasants, the fruits of empire were bitter indeed. The Second Punic War against Hannibal had devastated many fields in Italy. The other wars of the third and second centuries B.C.E. had left many fields ruined by years of neglect while the farmers were off campaigning. When the farmers came home, two things came with them. First of all, thousands of prisoners of war flooded Roman slave markets. This influx of cheap slave labor let rich Roman senators set up huge estates that competed with the free peasants already struggling to revive their farms. Added to this was an influx of cheap grain from Sicily (also from estates worked by slaves). Faced with such competition, thousands of peasants lost their farms and migrated to the cities, especially Rome.

Life in the cities was little better. Slaves there had also taken many of the jobs the peasants might have hoped for. Thus the dispossessed peasants became an idle urban mob dependant on various politicians for food and rent in return for political support. This led to untold squalor and the occasional cheap spectacles of gladiatorial fights and chariot racing, the proverbial "bread and circuses" of ancient Rome. Because of this, Roman politics became corrupt, violent, and split into two factions, the Optimates who drew their support from the Senate and other nobles, and the Populares who relied on the Tribal assembly and mob for support.

Provincial government was no better. The root of the problem was that Rome was trying to rule a large empire with an amateur city-state government. At first, extra praetors (judges), and later pro-consuls (ex-consuls) and pro-praetors (ex-praetors) were created to run the provinces for terms of one year. However, one year was not nearly enough time to learn about a foreign culture and how to govern it. Therefore, such governors were untrained, unsupervised, and unpaid. Being unpaid forced them to cover their expenses through corruption. Being unsupervised let them get away with almost anything they wanted. Being untrained meant they were usually incompetent. Even the creation of permanent extortion courts to try corrupt ex-governors only encouraged more corruption so they could bribe the jurors who were also their senatorial colleagues who hoped for similar leniency in the future when they were tried for corruption.

In addition there were no professional Roman bureaucrats to run the daily machinery of provincial government. Instead, governors brought personal friends and slaves. Tax collection was done through tax farming, a system where rich businessmen, known as equites, bought the right to collect the taxes of a province, paying the state the agreed sum and then over-taxing the provinces to cover their expenses and more.

These problems with dispossessed peasants and corrupt provincial government led to two problems with the army. For one thing, Rome’s army of peasant militia had been fine when Rome’s wars were close by and campaigns ended in time for harvest. However, long terms of service in overseas wars had ruined many farms through neglect, leaving fewer recruits able and willing to go to war, lowering the army's morale and efficiency. Second, the yearly turnover of governors led to inexperienced generals who suffered frequent military defeats.

This led to two reforms. First, generals created a long-term professional army by recruiting the dispossessed peasants, promising them land after the war as an inducement to enlist. They also had to supply them with their equipment since the Senate still felt only those who could afford to equip themselves should serve in the army. Therefore, the soldiers were more loyal to their generals than to the state (probably seeing little distinction between the two). The second reform was to extend the terms of provincial governors from one year to as many as five. This resulted in a few experienced, ambitious and rival generals.

These reforms triggered a vicious cycle where those few governors with armies had more scope for long-term campaigns and outright conquest of new lands. This upset the balance of power in the Roman Senate, between a small number of rich and powerful men and the majority of senators who had few opportunities for glory and riches. The combination of all these social, economic, administrative, and military problems bred a century of political turmoil, administrative unrest, and civil wars between rival generals.

FC30AThe Flow of Power in the Roman Republic

At the center of power was the Senate, an advisory body of 300 ex-office holders whose decrees (senatus consulta), while not technically laws, carried the virtual force of law. The Senate especially had jurisdiction over officials’ budgets, the technical legality of treaties and laws, and assigning tasks to magistrates (e.g., which ex-officials ruled which provinces and for how long). A ruling principle for the senatorial oligarchy as a whole was to maintain its power as a group without letting any individual members gaining too much power. In addition, the Senate exercised control over three main areas of Roman government: popular assemblies, ex-officials, and religious and traditional ceremonies and procedures.

There were two popular assemblies that the Senate needed to maintain control over. The Comitia Centuriata was originally a military assembly that elected the top officials in Rome (consuls, praetors, and censors) and voted on war and peace. It was originally organized into 193 bloc votes known as centuries, with the rich making up more centuries and thus given more votes. This was to reflect the heavier burden the rich, who could afford full armor, faced in battle. The tribal assembly (Comitia Tributa), which actually passed laws, could only vote on bills proposed by officials, who were also members of the Senate. In both assemblies open ballots where senatorial nobles could keep tabs on how their dependents (clientes) voted.

The primary means of control the Senate had over officials was the fact that after their one-year terms of office, ex-officials all returned to the Senate. This made it unlikely they would go against the wishes of their fellow senators. Therefore, the Senate controlled what laws were proposed and voted on through the consuls and praetors. Even the ten tribunes, who were supposed to protect the rights of the poor through the right to veto laws, had to go back and face the Senate after their year in office.

The Romans were religious, even superstitious people who place great value on omens and doing things by the exact right procedure to keep the favor of the gods. It just so happened the Senatorial nobles also controlled the priestly offices, and virtually all government procedures involved religious rituals that could block or negate government actions. Reinforcing this was the cursus honorum (ladder of honors) that dictated the minimum age, number of times, and order one could hold offices. Every five years, the Comitia Centuriata chose two censors, whose job was to expel unworthy senators and fill empty senatorial seats. Naturally, only senatorial nobles served as censors, making sure that the exclusive club of the Senate contained maintained the purity of its membership and control of the state.

FC31The Fall of the Roman Republic (133-31 BCE)

Pattern of decline

Rome's failure to adapt its city-state style government to ruling an empire triggered a century long pattern of events that would eventually lead to fall of the old oligarchy led by the Senate. Either out of genuine concern for reform, desire for personal gain and glory, or a combination of the two, an individual politician or general would introduce new, but also disruptive practices. These would weaken Roman customs, traditions, and institutions, especially the Senate. That would create the need and open the way for new figures to rise up that would introduce even more disruptive practices, and so on. Thus the cycle would keep repeating until the old order was destroyed. There were five main figures this process brought to the forefront of Roman politics and who in turn perpetuated the cycle, allowing the rise of the next figure: Tiberius Gracchus, Gaius Gracchus, Marius, Sulla, and Julius Caesar. Not until Caesar's nephew and heir, Octavian, seized power would the cycle be broken and a new more stable order established in place of senatorial rule.

First attempts at reform: the Gracchi

In 133 B.C.E., Tiberius Gracchus became tribune. He saw that many of Rome's troubles revolved around the decline of the free peasantry who were flocking into the cities. Therefore, he proposed a bill to give land to the idle mob and re-establish them on their own farms. The land he proposed using was public land owned by the state that, unfortunately, was controlled by rich and powerful senators who most likely would be reluctant to give it up.

Seeing that the Senate could well be hostile to his plan, Tiberius did several rather unheard of things. Although not necessarily illegal, his actions certainly flaunted the deep-seated traditions by which Roman government had operated for centuries. For one thing, Tiberius by-passed the Senate and went directly to the tribal Assembly where his bill had a better chance to pass. When the Senate bribed another tribune to veto the bill, Tiberius took the radical step of impeaching the man. With that done, the land bill passed despite the fury of the Senate. In order to get money to start the peasants on their new farms, Tiberius had the assembly appropriate the treasury of Pergamum, which had just been willed to Rome. Financial and foreign matters were both the realm of the Senate, but Tiberius and the assembly just shoved that aside as well. Tiberius then tried to do away with one more tradition by running for re-election as tribune. This was too much, and in the discussion of its legality, a riot broke out that ended with the death of Tiberius and 300 of his followers. Civil violence was starting to be used to decide an issue in Roman politics.

Despite his good intentions, Tiberius' methods hastened the decline of the Republic more than they helped it. For one thing, he made the Tribal Assembly, which controlled the Urban Assembly, a major factor in Roman politics. Likewise, he weakened the senatorial nobles who had traditionally run Rome. This gave rise to factional politics of the Optimates and Populares, causing Roman politics often to degenerate into little more than bribery contests and street fights to win power. However, Tiberius' reforms also had some positive results as some 75,000 people were put back on farms in the decade after his death. However, there was still a lot of work to be done, and in 123 B.C.E. Gaius Gracchus, Tiberius' younger brother, became tribune.

An ardent reformer like his brother, Gaius passed a law guaranteeing cheap grain for the urban poor. Later politicians would make that grain free at state expense. Another move to weaken the Senate and gain allies was to give the equites (rich businessmen) control of the juries in the courts that tried Roman governors for corruption. While this prevented corrupt senatorial governors from relying on their senatorial friends to acquit them in the extortion courts, it hardly solved the corruption problem. Now equites who had bought the right to "farm" a province's taxes could threaten the governor with conviction in the extortion courts if he did not let them take all they wanted from the provincials. This also made the equites a new force in Roman politics, symbolized by special seats at the games and the right to wear distinctive rings. At the same time, it further weakened the Senate.

The Senate was understandably nervous about how far this new Gracchus would go, and tried to outbid him for popular support. Unfortunately, Gaius overstepped himself by proposing citizenship for the Italian allies. This was unpopular with the mob, which jealously guarded their citizenship as the only thing they had left to make them feel special. As a result, a riot broke out (probably with some help from the Senate), and Gaius was killed much as his brother had been.

Marius and the Roman army

The next figure to rise up was Gaius Marius, a man of equestrian rank and opposed to the senatorial nobility. Marius' rise to power started when he was serving in the army in North Africa against the Numidian king Jugurtha. The war in itself was not too important except that it showed the further corruption of Roman politics. Through a series of intrigues against his general, Marius got leave of absence to get elected consul. He then had the Tribal Assembly give him command of the war in place of his former general, Metellus. Marius and an ambitious junior officer named Sulla finished off Jugurtha and Marius got the credit. This set him up for the next big step in his career.

For several years, the migrations of some Germanic tribes known as the Cimbri and Teutones had been wreaking havoc in the north. When they turned on Rome in earnest and mauled a Roman army in Gaul in 105 B.C.E., panic set in and Rome looked for a savior. That man, of course, was Marius, the conqueror of Jugurtha. He was elected to an unheard of six straight consulships in order to prepare the army for the northern menace.

Marius' main legacy was a long overdue reform of the army. Rome's extended campaigns required a long-term professional army to replace the reluctant and inefficient peasant draftees Rome had used till now. Marius took the final steps of making it just that, with volunteers serving instead of peasants hauled off their farms. Marius' recruits came largely from the unemployed mob lured by the promise of land after their service was over. This had three main effects. For one thing, since these recruits were too poor to supply their own equipment, the state had to supply it, thus making equipment and training more regular and the army more efficient. Along these lines, professional soldiers could devote all their time to training which, combined with the proverbially tough Roman discipline, also made for a very effective army.

The third effect had to do with getting recruits. The main inducement to serve was that after his term of service, a veteran would receive a plot of land on which to start his own farm. However, since each general had to get a separate land bill passed by the Senate for his particular army, the soldier looked to his general for a land settlement. Therefore, the troops' loyalty tended to belong to the individual generals rather than the Senate. This meant that a new element, generals backed by their own armies, had become a factor in Roman politics.

However, Marius' recruiting and tactical reforms created a much more efficient and professional army, which is what Rome needed at this time. In Marius' sixth consulship, the Cimbri and Teutones finally got around to invading Italy after a leisurely rampage through Spain and Gaul. The newly reformed legions cleverly maneuvered the invaders into a bad position and then destroyed them under the hot Italian sun. Marius was the hero of the hour and acclaimed the Third Founder of Rome after the legendary Romulus and Camillus.

Marius may have been a good general, but he was a mediocre politician. When his ally, the tribune Saturninus, tried to seize power, a riot broke out. Marius thus found himself in the difficult spot of having to suppress his own rioting supporters. He did his duty, killed many of his followers, and lost most of his popularity as a result. After all this, he retired from politics, waiting for a new opportunity for military glory.

Sulla and the First Civil War

For some time, one of the hot issues of the day in Rome was citizenship for the Italian allies. While the Romans had previously been fairly liberal in granting different allies full citizenship, lately they had been satisfied to grant only second class, or Latin, citizenship. Unfortunately, the Italian allies were not nearly as satisfied with this and were agitating for full rights. We have already seen how this issue cost Gaius Gracchus his life. When another Roman, Marcus Livius Drusus, proposed full citizenship and was assassinated, Italian frustration boiled over into open rebellion. This revolt, known as the Social War, or war of the allies (9l-88 B.C.E.), saw Rome faced with a formidable Italian enemy trained in Roman tactics. In fact, it was so formidable that the Senate did the one thing it could to defuse the rebellion: it granted full citizenship to any Italians who remained loyal or immediately laid down their arms. This clever move stripped the rebellion of much of its support. The Senate then called on two of its ablest generals, Marius and Sulla, to finish the job. In the end, the rebellion was put down, but the Italians had gained full citizenship, definitely a step forward for Rome and Italy.

The Social War had brought a poor, but very ambitious senatorial noble to the forefront of Roman politics, Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Always on the lookout for the opportunity for power and glory, he found it right after the Social War in the form of a new war in the East against Mithridates, king of Pontus on the Black Sea. Seeing widespread resentment against Rome for its corruption and mistreatment of the provincials in Asia Minor, Mithridates, stirred up a revolt that supposedly massacred 80,000 Italians in Asia Minor in one day. With Rome still preoccupied with the Social War, Mithridates overran Roman Asia and then crossed into Greece (90 B.C.E.). However, once the Social War was over, Rome was ready to tangle with the king of Pontus.

The problem was: which of Rome's generals, Marius or Sulla, should get command of the war? Sulla, who was the consul at this time, legally had the right and initially got it. But as soon as he set out for the port of Brundisium, Marius' followers seized power and gave Marius the command. Sulla then took the unprecedented step of marching on Rome with Roman troops to drive Marius' followers away in flight. However, once Sulla had left again for the East, Marius returned to Rome and seized power again. He was now a bitter old man who started a reign of terror so bloody that his own followers had to put an end to it. Several days into his seventh consulship, Marius died, but his followers remained in power and sent an army to relieve Sulla in the East.

Meanwhile, Sulla had been driving Mithridates from Greece. After two desperate battles and a long terrible siege of Athens, Mithridates fled to Asia Minor. Luckily, the Roman army and general sent to relieve Sulla concentrated more on Mithridates and let Sulla track him into Asia. Mithridates sued for peace and Sulla gladly granted it so he could turn on his enemies in Rome.

What followed was the First Roman Civil War (83-82 B.C.E.). Sulla's tremendous energy and drive made short work of his enemies, and he entered Rome in triumph. His first act was to massacre any of his enemies, including some 90 senators and 2600 rich equites. Among those narrowly escaping Sulla's wrath was the defiant young son-in-law of Marius, Julius Caesar. Sulla then became dictator, and reformed the government to put the Senate back in firm control of the state, just like in the good old days. A year later, Sulla abdicated his powers and retired to the luxury of his villa where he died soon afterwards (78 B.C.E.).

Sulla's settlement did little or nothing to solve Rome's real problems. And after his strong hand was removed, political turmoil returned in full force. The first man to take advantage of this situation was Pompey, one of Sulla's young army officers. Pompey's early rise to power was the result of some drive and energy, but also a good deal of luck. He held several military commands before holding public office. That was illegal, but apparently of little account anymore in Rome. Quite a bit of luck accompanied Pompey as he destroyed Marius' supporters holding out in North Africa and Spain. Also, by chance, as he returned to Rome from Spain, he encountered and mopped up the remnants of a great slave revolt led by a gladiator named Spartacus. Another of Sulla's former officers, Crassus "Dives" (the rich), had actually broken the back of this slave revolt that had terrorized Italy for two years. Nevertheless, Pompey claimed partial credit.

Nerves were on edge as the two potentially hostile Roman generals and their armies were poised on the outskirts of Rome. Luckily, Pompey and Crassus made their peace and together became consuls for 70 B.C.E. Pompey's star just kept rising. Soon afterwards he received an extraordinary command to clear the Mediterranean of pirates who had infested its waters for years and were even threatening Rome's grain supply. After sweeping the seas clear of these pirates in an amazingly short time, Pompey received another important command. This time he was sent to fight Mithridates of Pontus who had revived his struggle against Rome. Once again luck was with Pompey, because another general, Lucullus, had already done most of the job. Still, it was Pompey who finally crushed Mithridates (who then committed suicide), and it was Pompey who got the credit and triumphal parade. He then spent the next few years marching through the Near East and reorganizing it along lines more favorable to Rome by creating new Roman provinces in Asia Minor and Syria (where he put a final end to the decrepit Seleucid dynasty) and establishing client kings loyal to himself and Rome elsewhere. In 6l B.C.E., Pompey finally returned to Rome, but this was where his star began to wane.

The rise of Julius Caesar

Pompey, like Marius, may have been a good military man, but he was not much of a politician. Trusting in the power and glory of his name alone, he disbanded his army before he got a land settlement for his veterans from the Senate. When the Senate refused to help him out, Pompey found two allies with whom he formed the First Triumvirate, an informal political alliance designed to control Roman politics. One of these was his old colleague, Crassus the Rich. The other was a popular young politician, Julius Caesar. With Pompey's military reputation, Crassus' wealth, and Caesar's popularity with the mob, the Triumvirate should and could rule Rome effectively.

The first order of business was to elect Caesar as consul for 59 B.C.E. He had a wild term of office where he ran roughshod over the Roman constitution. Using a good deal of intimidation, he got Pompey's troops their land and himself a lucrative military command in Gaul (modern France) where he was determined to gain a military reputation equal to Pompey's.

Caesar had little military experience before going to Gaul. However, one would never have known it by looking at the masterful way he brought it under Roman control in a mere ten years. We can hardly imagine the sense of relief to the Romans now that the menace of the northern tribes was further removed from Rome. The Roman conquest of Gaul was also an important step in the process of civilizing Western Europe. Although Gaul was already showing major steps in that direction, the Roman conquest made it heir to the high cultures of the ancient Near East and Greece by way of Rome. It should be noted that, as in the case of Alexander, the glory of Caesar's victories obscured the butchery of countless thousands of innocent people and blurred the distinction of who was civilized and who was barbarian.

During his ten years in Gaul, Caesar also built up a highly efficient and intensely loyal army that could brag of exploits to rival and even surpass those of Pompey's army. Naturally, this caused jealousy and suspicion on Pompey's part. Crassus, whose influence helped keep the Triumvirate together, was killed fighting the Parthians, nomadic tribesmen who had taken much of the old Persian Empire's Asian lands from the now extinct Seleucid dynasty. The death of Julia, Caesar's daughter and Pompey's wife, removed another bond holding the two men together. Day by day, tensions grew as rival political gangs disrupted the streets of Rome with their clashes and the Senate started to back Pompey in opposition to Caesar. Caesar, fearing for his life after he gave up his army, led his troops into Italy and started another civil war (49-45 B.C.E.).

Pompey was no match for Caesar's quick, decisive, and brilliant generalship, and was crushed at the Battle of Pharsalus in Greece in 47 B.C.E. He fled to Egypt where Ptolemy XII who feared the wrath of Caesar murdered him. Soon afterwards, Caesar showed up in Egypt where he spent the next year supporting Ptolemy's sister, Cleopatra, in a civil war against her brother. He then set out to meet Pompey's other allies and followers. In a whirlwind series of campaigns in Pontus, North Africa, and Spain, Caesar crushed the Pompeian forces. By the end of 45 B.C.E., Caesar was the undisputed master of the Roman world and was appointed dictator for life.

Unfortunately, the problems plaguing Rome were too complex to be solved by mere military victories. Caesar did carry out several reforms. He extended citizenship outside of Italy for the first time. He also changed the old Roman lunar calendar to the more efficient and accurate Egyptian solar calendar, which we still use today with some minor adjustments. However, even Caesar seemed to be at a loss for finding solutions to the deep-seated problems plaguing Roman society and instead planned a major campaign against Parthia. The prospect of Caesar gaining more military glory and becoming even more of a dictator worried a number of senators who formed a plot against his life. On March 15, 44 B.C.E., the eve of his setting out on his campaigns, the conspirators surrounded Caesar in the Senate house and brought him down with twenty-three dagger wounds. Ironically, he fell at the foot of the statue of Pompey.

Octavian, Antony, and two more civil wars (44-31 B.C.E.)

Unfortunately, Caesar's murder did nothing to solve Rome's problems as there were always new generals waiting to follow in the footsteps of Marius, Sulla, Pompey, and Caesar. In this case, two men emerged in that capacity: Marc Antony, one of Caesar's most trusted officers, and Octavian, Caesar's 19 year old nephew and chosen heir. Octavian was young, inexperienced in politics and military affairs, and somewhat sickly. No one much gave him a very big chance to survive in the vicious snake pit of Roman politics. Surprisingly, he proved himself quite adept at politics, playing the Senate off against Antony while the Senate thought it was using him in the same way. He then did an about face and allied with Antony and another general, Lepidus, to form the Second Triumvirate.

The first act of the new triumvirate was to clear its enemies out of Rome in a bloody purge. Among the victims was the great Roman statesman, orator, and philosopher, Cicero. We still have many of his speeches and letters that tell us a great bit about life and politics in the crumbling Republic. After this purge, there were still several of Caesar's murderers to contend with in Greece where they were building an army. In the third Roman civil war in less than 50 years, Antony and Octavian tracked down the conspirators, Brutus and Cassius, and destroyed their forces at Philippi (42 B.C.E.).

This put the Second Triumvirate in undisputed control of the Roman world. Lepidus was gradually forced out of the picture, leaving Antony and Octavian to split the spoils. Antony took the wealthier eastern provinces and got involved in his famous romance with Cleopatra of Egypt. Octavian took the less settled West along with the Roman homeland and recruiting grounds of Italy. As one might expect, tensions mounted between the two men and finally erupted into another civil war. At the battle of Actium in 3l B.C.E., Octavian's fleet crushed the combined navies of Antony and Cleopatra. After a desperate defense of Egypt, both Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide, leaving Octavian as sole ruler of the Roman Empire. It seems ironic that a non-military man should emerge as the final victor in these civil wars and bring them to an end. However, as a non-military man, Octavian saw that the solutions to Rome's problems involved much more than marching some armies around. It would be Octavian, known from this point on as Augustus, who would bring order to Rome and inaugurate one of the most long lasting periods of peace and prosperity in human history: the Pax Romana, or Roman Peace.

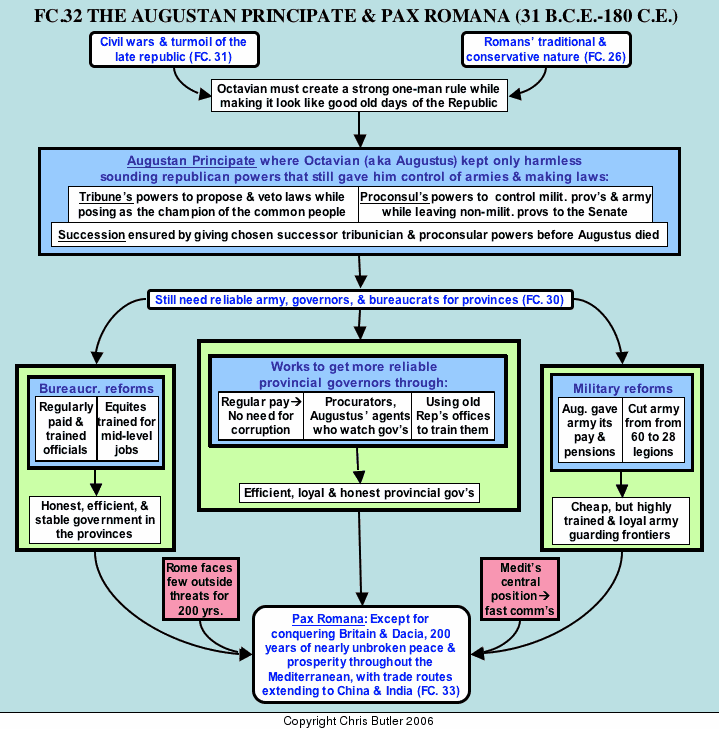

FC32The Augustan Principate (31 BCE-160 CE)

Octavian's victory over Antony and Cleopatra ended a century of civil turmoil and decay. When he returned to Rome in triumph in 29 B.C.E., everyone anxiously wondered how he would use his victory. The Roman people and Senate heaped all sorts of honors on Octavian: triumphal parades, political offices, and titles, including that of Augustus ("revered one"), by which title he has been known ever since.

Augustus saw that there were two basic needs he had to satisfy in order to avoid the pitfalls of the past century. He saw two basic needs he had to satisfy. For one thing, the civil wars and turmoil of the last century clearly showed the need for a strong one-man rule backed by the army. Second, the traditional and conservative nature of the Romans made it mandatory that he make any reforms at least appear to be like the good old days of the Republic with its elections and many political offices. Satisfying these two needs required a politician cleverer than Marius, Sulla, and even Caesar himself. Luckily for Rome, it had such a man in Augustus who founded a new order known as the Principate after his honorary title of princeps (first citizen).

Augustus' solution was to take the army and law making powers and disguise them with harmless sounding Republican titles. Out of all the Republican offices he took only two main offices, or more properly powers without the offices: those of tribune and proconsul (provincial governor). Having special tribunician powers allowed him to propose laws to the Senate and assembly. Being just a tribune, one of the humblest offices in Rome, made Augustus look like a man of the people and their protector. However, his title of princeps gave him the right to speak first before all other officials instead of having to wait his turn like other tribunes.

Proconsular power gave Augustus all the strategically placed provinces with armies, thus giving his tribunician powers the clout to pass any laws he wished with a minimum of resistance. In order not to appear too greedy, Augustus gave the Senate control of the non-military provinces. In fact, one or two of these even had a legion with which the Senatorial governors could play soldier. In such a way Augustus took effective control of the laws and army while leaving the Republic intact, at least on the surface.

Although his own position was secure, Augustus still had to provide for a smooth succession so his system would continue peacefully after he died. He needed to appoint a successor much like a king would, but once again, make it look like the Republic. He solved this with typical Augustan shrewdness by having his chosen successor assume the powers of tribune and proconsul while he was still alive. Therefore, when Augustus died, the new emperor would already hold the important offices to guarantee a smooth transition of power. Over time, and the memories of the Republic faded would fade and it would be taken for granted that the emperor's son or chosen successor should be the next emperor, even if he did not already hold the appropriate powers.

Once he had secured his own position, Augustus still had to provide for three things in order to rule the empire effectively: honest and efficient provincial governors, an honest and efficient bureaucracy to help them, and a loyal and efficient army to defend the frontiers instead of making trouble in Rome. Augustus did two things to ensure honesty and efficiency in his governors. For one thing, he paid officials regular salaries instead of leaving it up to them to make up for their own losses at the expense of the provincials. This at least eliminated the more blatant need for corruption. Augustus also had his own personal agents, called procurators, to keep an eye on officials in the provinces. Any corrupt governors would be tried by the Senate. However, it was unlikely that a governor's fellow senators would be so lenient with him as before, because Augustus kept a close eye on these proceedings to ensure justice. Together, these reforms gave Augustus the efficient and honest governors he needed.

Augustus ensured more efficient governors by reviving the old cursus honorum (ladder of honors), whereby aspiring senatorial politicians would gain necessary experience and training by serving in the army and then holding a sequence of old Republican offices. At the same time, it maintained the fiction of the Republic still carrying on by making good use of the old Republican offices. Augustus obtained trained middle level officials from the rich business class of the Equites. They had their own cursus honorum to go through before being eligible for various lucrative positions such as command of the fleet, Rome's grain supply and fire brigades, the Praetorian Guard (the emperor's own personal regiments), and the governorship of Egypt (kept as Augustus' private domain).

Augustus also needed trained bureaucrats to do the daily work of running the empire. Previously, senatorial governors would take their friends and slaves to fill these positions, which led to all sorts of inefficiency and corruption. Augustus replaced this system with a professional class of tax collectors and record keepers who held their jobs for extended periods. He also ended tax farming, where the government auctioned off the right to collect the taxes. This had been one of the worst sources of abuse under the Republic. These reforms provided the provinces with an honest, efficient, and stable government. There was also the need for trained people to fill many “middle-level” jobs, to oversee such things as the fleet, Rome’s grain supply, the emperor’s Praetorian Guard, and his new para-military fire brigade that doubled as a police force to keep order in Rome. In this case, Augustus used the rich equites class, training them with a cursus honorum similar to that of the Senatorial class before they were eligible for these critical positions.

There were two issues to resolve with the army: its loyalty and expense. In terms of loyalty, since Augustus' proconsular powers gave him control of the provinces and the armies within them, there was technically only one commanding general (imperator) of nearly all the Roman armies: himself. Obviously, any emperor, especially a non military man like Augustus, would have to appoint men to lead at least some of the troops spread out along Rome's vast frontiers. However, the troops stayed loyal to Augustus, not their immediate generals, for one good reason. It was Augustus now, not the generals, who paid soldiers their regular pay and pension, generally with coins that bore the emperor's image as a constant reminder of who took care of the troops. The central government, meaning Augustus, once again had control of its armies. Occasionally, the troops would rediscover the fact that they held the key to power and would revolt to put their own generals on the throne. For the most part, they stuck to the business of guarding the frontiers and left governing to the emperors in Rome.

Finally, in order to increase efficiency and cut costs, Augustus reduced the army from 60 legions to 28. He generally placed these along the frontiers most threatened by invasion: the Rhine and Danube Rivers in the north and the Euphrates River in the east. An equal number of auxiliaries (light infantry and cavalry) were also maintained there. The total number of troops Rome had amounted to roughly 250-300,000 men defending an empire of possibly 50,000,000 people. Such a small force for so large an empire had to be efficient. The Roman legions during the Principate comprised the most tightly disciplined and efficient army of antiquity, and everyone knew it. It was their reputation as much as their swords that defended the frontiers and gave the Mediterranean two centuries of peace. Rome was also lucky in two ways at this time. First it faced no major threats on its borders. Second, the Mediterranean, as the central geographic feature of the empire, allowed much faster communications and reaction time during emergencies.

The Empire after Augustus

Augustus died in 14 C.E., but his work lived on long afterwards. For nearly two centuries afterward, the Roman world would experience peace such as it had never known before or since. Its government was well trained, efficient, and honest, while its legions kept the frontiers and interior provinces secure. Roman political history during this time is not very exciting, because relatively little happened besides a few palace scandals in Rome.

The empire expanded very little during this time, just rounding out its control of the Mediterranean and invading Britain. Occasional wars would flare up in the East with the Parthians and in the north with various Germanic tribes, but there were no serious threats to the Empire. The vast majority of people in the empire never experienced war and invasion. Even the troops on the frontiers often saw so little action that they were kept busy and in shape by building the vast network of roads Rome is so famous for. Peace and prosperity brought trade, both within the empire and beyond its borders with such exotic places as India and China far to the east. Merchants traveled the legionary roads and the Mediterranean free from fear. Peasants harvested their crops undisturbed by war. And the legionary camps on the frontiers grew into permanent cities.

This was certainly a golden Age for civilization. However, even times of peace and prosperity can carry within them the seeds of their own decay. That was true of the Roman Empire in the second century C.E., although few if any people recognized the problems within their society. At the same time, pressures were starting to mount against the northern frontiers. Together, these internal problems and external pressures would combine to destroy the Roman Empire and begin the transition from the ancient world to the Middle Ages.

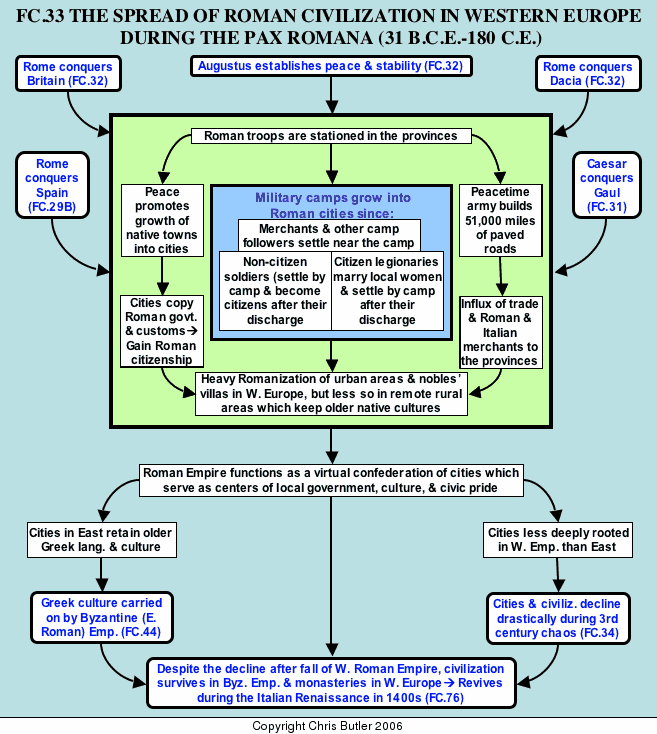

FC33The Pax Romana & spread of Roman civilization

One of the greatest legacies of the Pax Romana was the spread of Roman culture to Western Europe. Roman rule in the semi-civilized areas of Western Europe (Gaul, Britain, and Spain) and Augustus' establishment of peace during the Pax Romana meant that there were Roman troops permanently stationed in the provinces. This helped Romanize and civilize the provinces in the West in three ways. First, as the legionary camps became permanent settlements, merchants, families, and other sorts of camp followers settled down around them. In time, these army camp settlements became towns and cities, whose military origins are still reflected in Britain in such place names as Winchester and Lancaster (from the Latin word for camp, castra). After they were discharged from the army, legionaries, who were Roman citizens, and auxiliaries (non-citizen soldiers who received Roman citizenship after their terms of service) would often settle in these towns, marry local women, and raise their children as Roman citizens.

Along these lines, the peaceful conditions brought on by the Pax Romana, promoted the growth of native towns into cities. Those cities whose leading citizens copied Roman styles of dress, language, architecture, and local government would earn Roman citizenship for their towns. The poorer citizens would then follow the leading citizens' leads, thus encouraging the spread of Roman civilization that way. Finally, with extended periods of peace, the Roman army spent much of its time building an excellent system of some 51,000 miles of paved roads stretching across the empire. While these roads' original purpose was to facilitate the rapid movement of Roman troops to trouble spots, they also promoted trade and the influx of Italian merchants into the towns of the western provinces.

In these three ways, the western provinces saw the heavy Romanization of their towns and also nobles on country estates who felt they had some incentive to copy Roman ways for personal advancement. However, there were limits to Romanization. For one thing, it only happened to any great extent in Gaul, Britain, and Spain where there was no long established civilization in place before the Romans came. By contrast, the Eastern provinces were already heavily influenced by Greek culture in the cities and native cultures in the countryside. In a sense, the Roman Empire was a bi-cultural empire, with Greek language and culture dominant in the East and Roman language (Latin) and culture and dominant in the West. (Coins in the East were even struck with Greek inscriptions.) In both East and West, the influence of these respective cultures was mainly limited to the cities and barely touched the countryside.

However, despite the serious decline of cities in the West during the Middle Ages, Roman culture would survive in the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire and thanks to the efforts of monks in the West who copied many works of Roman literature. As a result, there would be a resurgence of Roman culture during the Italian Renaissance where it would reassert itself as the foundation of Western Civilization.

FC34The near collapse of the Roman Empire (160-284 CE)

Why a society goes into decline and eventual oblivion is one of the most complex, interesting, and important questions one can ask in history. The decline and fall of the Roman Empire has especially fascinated historians down through the centuries. How could the most powerful empire in antiquity just come apart at the seams and disintegrate? While historians have focused on various causes ranging from barbarian invasions and moral decadence to the influence of Christianity and lead poisoning, the fact is that many factors combined to lead to the downfall of Rome and open the way into the Middle Ages. Furthermore, these different factors fed back on one another to aggravate the situation and also to make the process of decline more complex to trace.

Mounting problems (161-235 C.E.)

The first signs of trouble came in the reign of Marcus Aurelius (16l-180 C.E.), the last of the so-called "Good Emperors". When he came to the throne, the Roman Empire still seemed to be experiencing a golden age. The government was efficient, fair, and honest. The army secured the frontiers from invasions. And the economy was healthy in both the countryside and cities. However, during Marcus' reign things started to fall apart. There were five major problems feeding into Rome's decline.