Readings & Flowcharts

Outline of History

-

Prehistory the rise of civilization, and the ancient Middle East to c.500 B.C.E

-

Prehistory and the rise of Civilization to c.3000 B.C.E.

-

Biological, Cultural, and Technological Evolution In History

-

Introduction

-

The “Rubber Band Theory”

-

An overview of the flow of history

-

The challenges of modern society: the rubber bands stretched

-

-

A Possible Scenario of Human Evolution

-

Where to start?

-

Out of the trees

-

Technological and cultural developments since the Australopithecines

-

Fire.

-

The Ice Ages

-

Accelerated technological development

-

Speech

-

-

A Possible Scenario For The Evolution of The Family and Gender Roles

-

Gender differences in the species

-

-

The Birth of Agriculture and Its Effects

-

Introduction

-

Why Eurasia and Mesopotamia?

-

Why Mesopotamia?

-

The invention of agriculture

-

-

The Rise of Cities and Hydraulic Civilizations (c.8000-3000 B.C.E.)

-

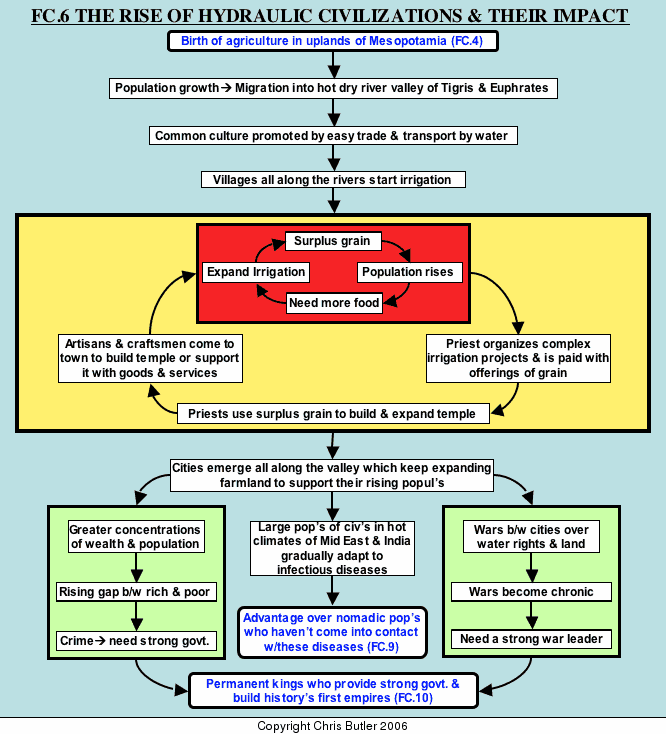

The rise of hydraulic civilizations

-

-

The Birth of Writing and Its Impact

-

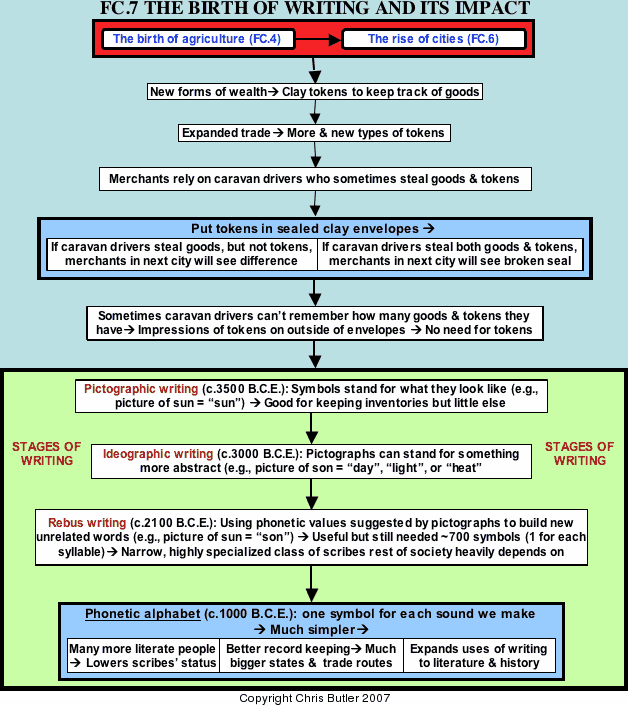

Prelude to Writing

-

Different stages of writing

-

Scribes and education

-

Results of writing

-

-

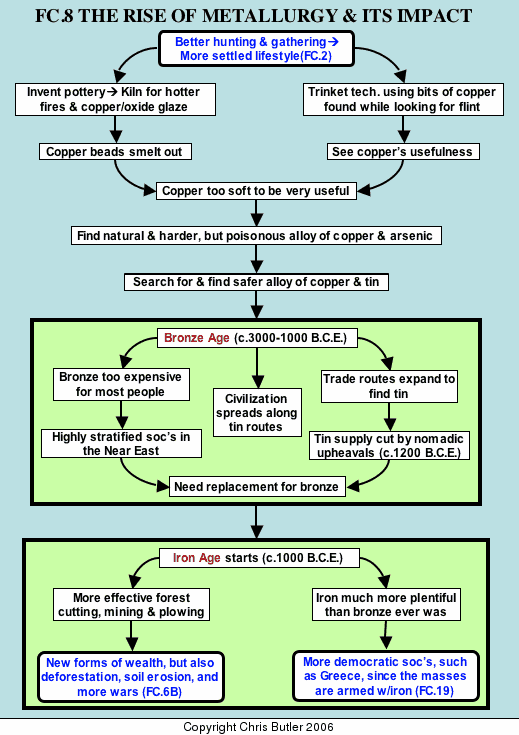

The Birth of Metallurgy and Its Impact

-

Introduction

-

The ages of metals

-

-

-

The ancient Middle East (c.3000-323 B.C.E.)

-

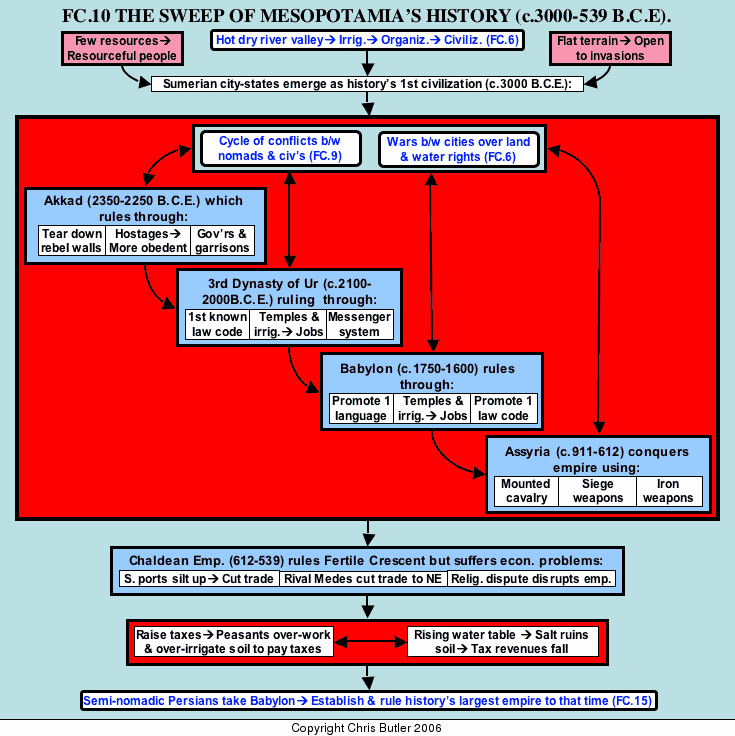

The Sweep of Mesopotamia's History (c.3000-529 B.C.E.)

-

Introduction: the environment

-

Sumer: myth and history (c.2800-2350 B.C.E.)

-

The Akkadian Empire (c.2350 - 2250 B.C.E.)

-

Sumer's last flowering: the Third Dynasty of Ur (c.2100-2000 B.C.E.)

-

Hammurabi and the Babylonian Empire (c.1750-1600 B.C.E.).

-

The horse and chariot (c.1650 B.C.E.)

-

The First Assyrian Empire (c.1365-1100 B.C.E.)

-

The Second Assyrian Empire (911-612 B.C.E.)

-

The Neo-Babylonian or Chaldaean Empire (612-539 B.C.E.)

-

-

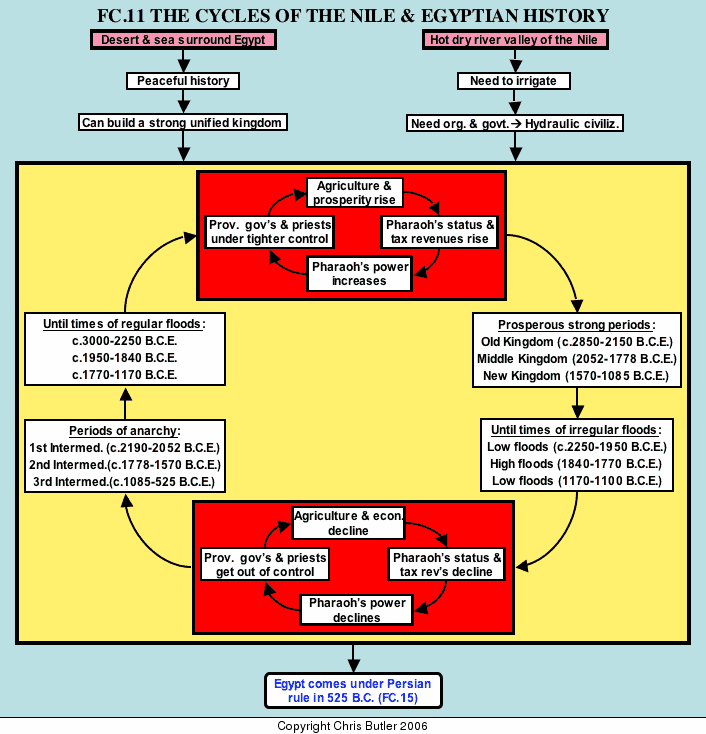

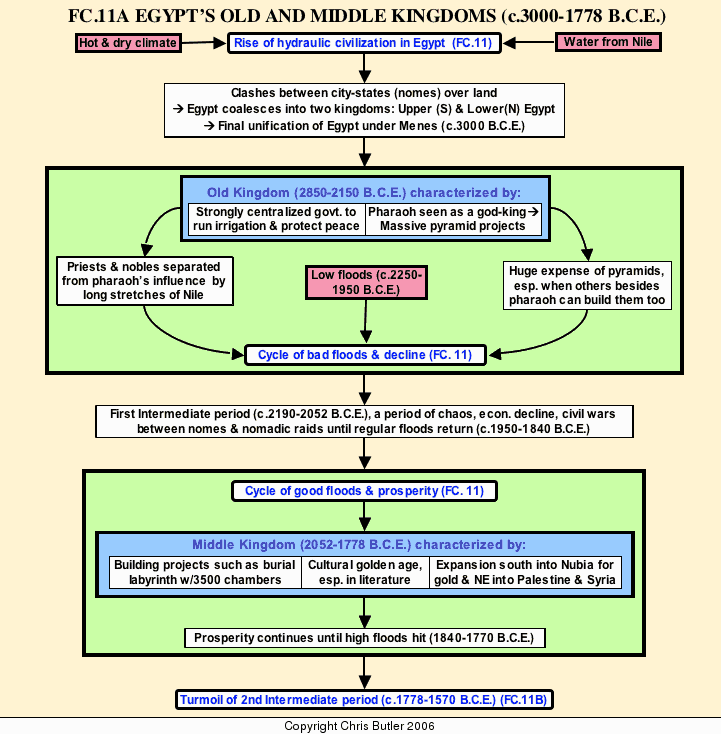

Egypt’s Old and Middle Kingdoms (2850-2052 B.C.E.)

-

The Old Kingdom (c.2850-2190 B.C.E.)

-

The First Intermediate Period (2190-2052 B.C.E.)

-

The Middle Kingdom (2052-1778 B.C.E.)

-

-

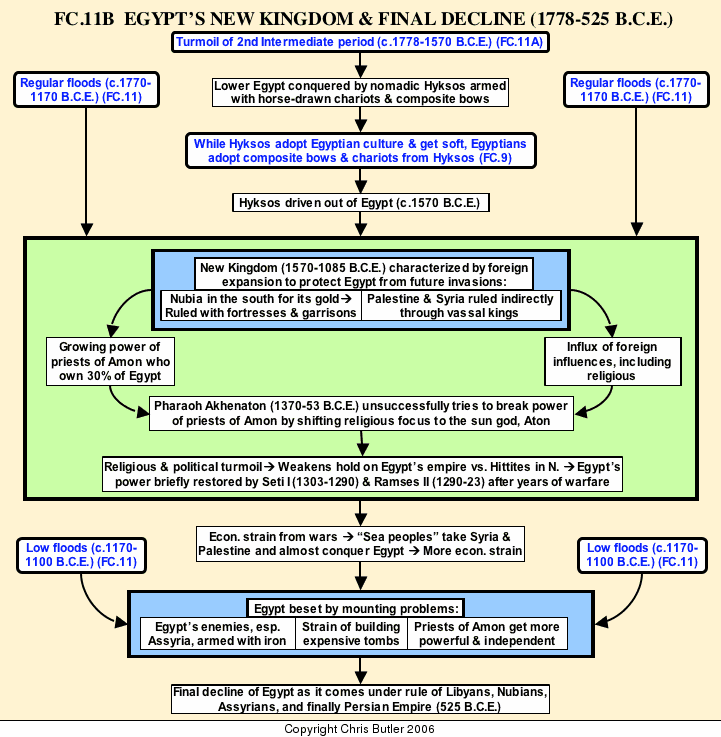

Egypt’s New Kingdom and Final Decline (1778-525 B.C.E.)

-

The Second Intermediate Period (1778-1570 B.C.E.)

-

The New Kingdom (1570-1085 B.C.E.)

-

Final decline (c.1085-525 B.C.E.)

-

-

The Indus River Civilization and The Pattern of India's History

-

The pattern of Indian history

-

-

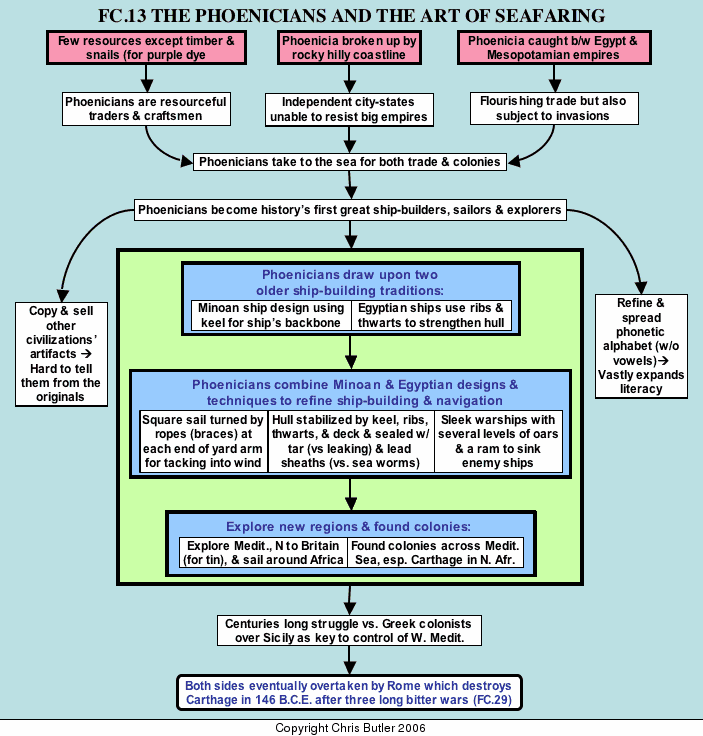

Masters of The Sea: The Phoenicians (c.1200-500 B.C.E.)

-

Geopolitics

-

Phoenician exploration and colonies

-

-

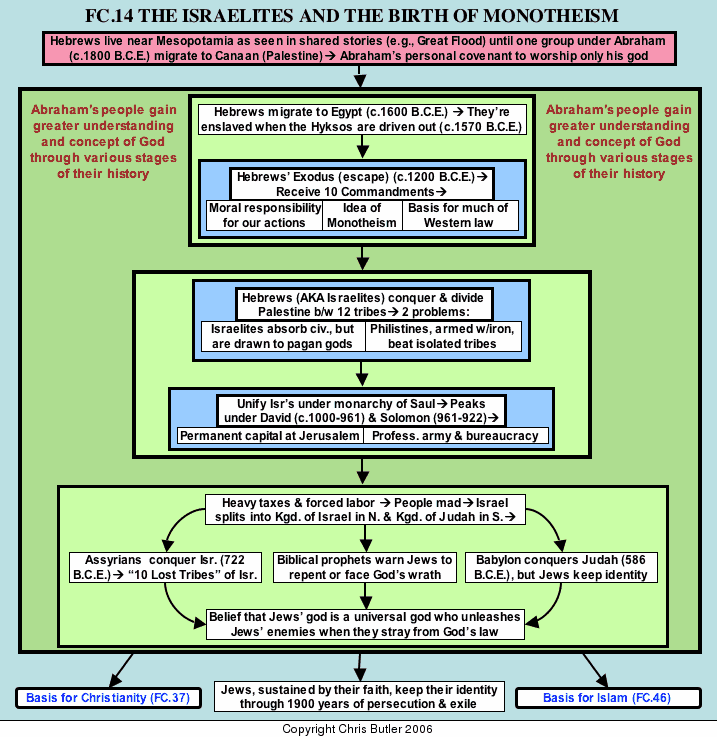

The Israelites (c.2000-500 B.C.E.)

-

Introduction

-

The Patriarchal period (c.2000-1650 B.C.E.)

-

The Egyptian Period and Exodus (c.1650-1200 B.C.E.)

-

Israel (c.1200-586 B.C.E.)

-

The divided kingdom (922-586 B.C.E.)

-

-

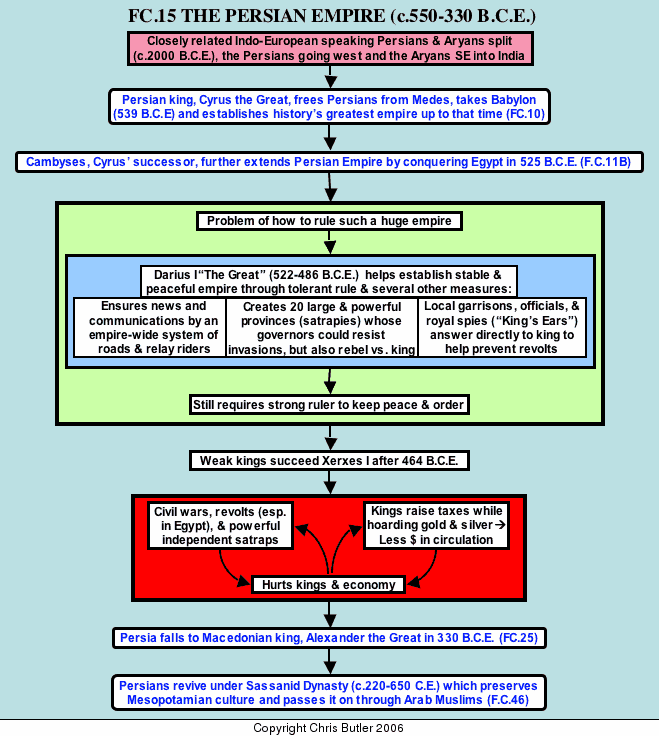

The Persian Empire (c.550-330 B.C.E.)

-

Introduction

-

Cyrus the Great and the Rise of Persia (c.550-522 B.C.E.)

-

Darius I "the Great" and the consolidation of the Persian Empire

-

Religion

-

Decline and fall (c.464-330 B.C.E.)

-

-

-

-

Birth of Western civilization: Greece, Rome, and Europe to c.1000 C.E.

-

-

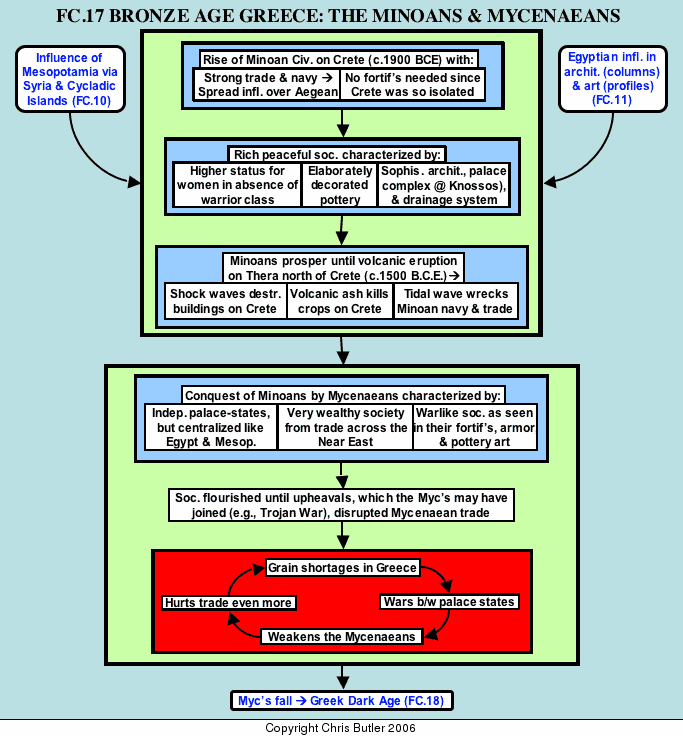

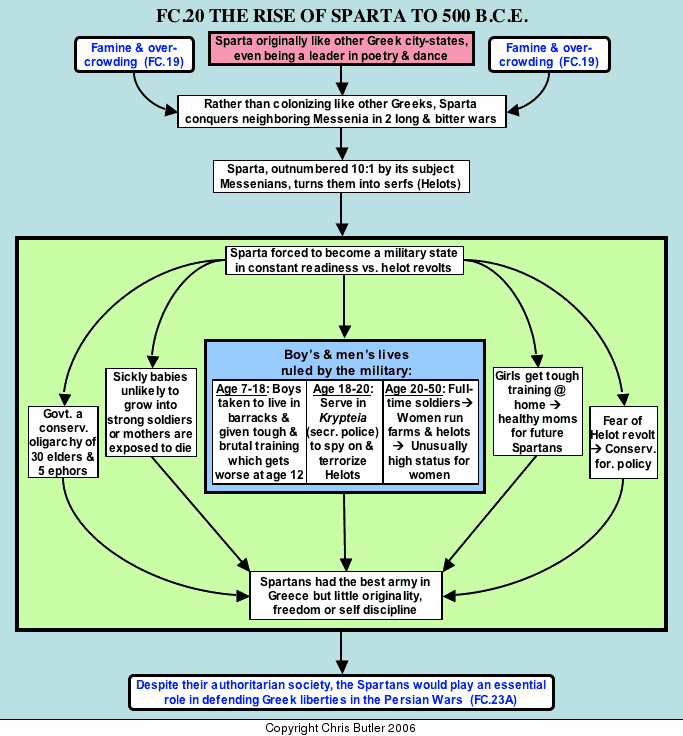

Bronze Age Greece: The Minoans & Mycenaeans (c.2500-1100 BCE)

-

Introduction

-

The Minoans (c.2000-1500 B.C.E.)

-

-

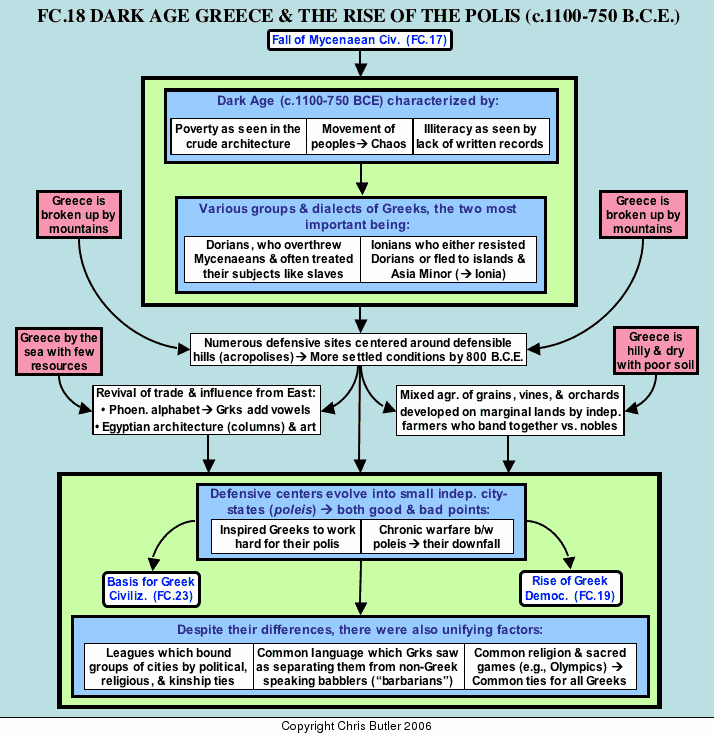

The Dark Age of Greece & The Rise of The Polis (c.1100-750 BCE)

-

Introduction: the Dark Age of Greece

-

The birth of the Polis

-

-

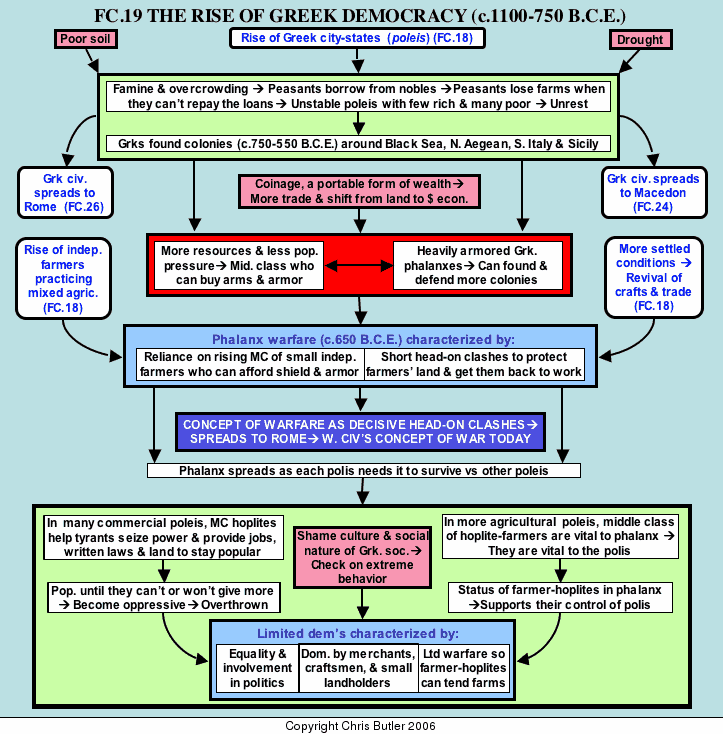

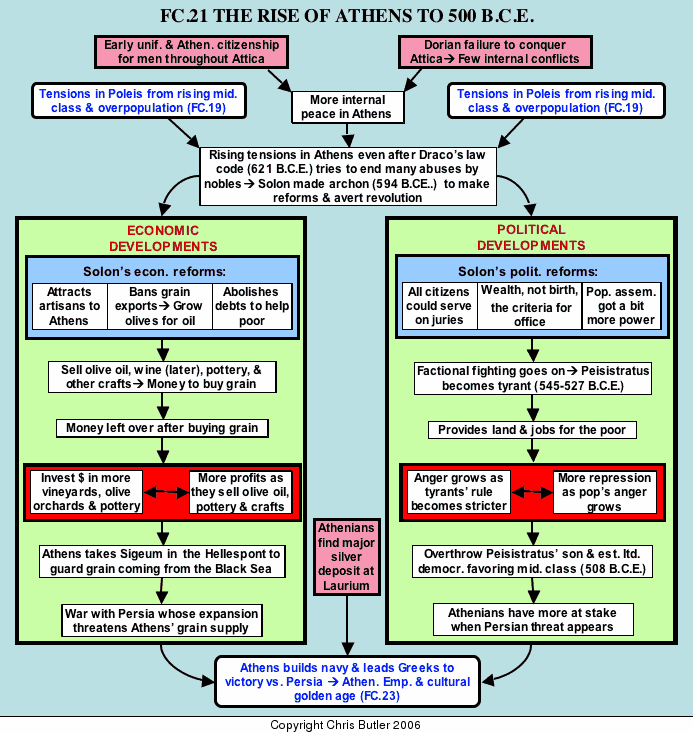

The Rise of Greek Democracy (c.750-500 BCE)

-

The Age of Colonization (c.750-550 B.C.E)

-

The Western way of war

-

The rise of Greek democracy

-

-

-

Economic reforms

-

-

Greek Philosophy From Thales To Aristotle (c.600-300 BCE)

-

Introduction

-

The Milesian philosophers

-

The nature of change

-

-

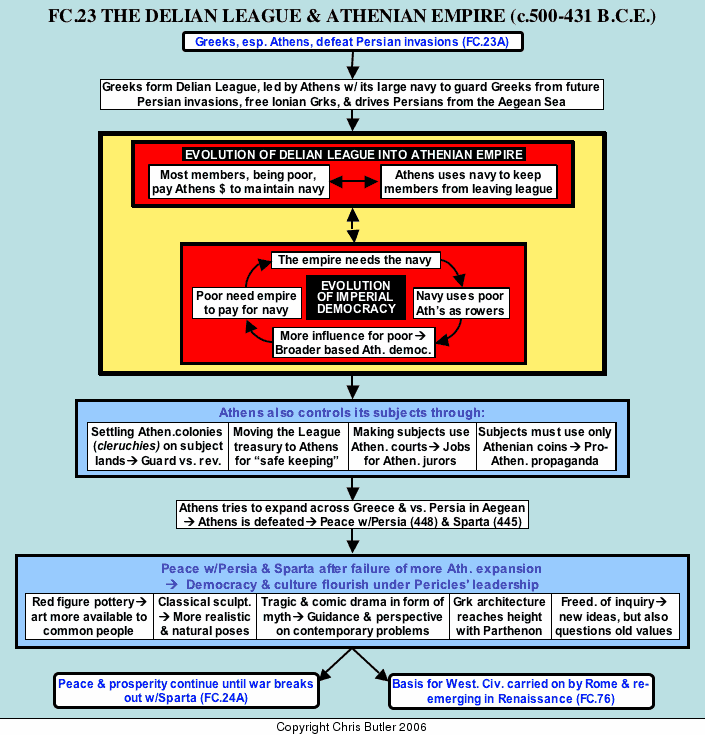

The Delian League and The Athenian Empire (478-431 BCE)

-

Formation of the Delian League

-

From Delian League to Athenian Empire

-

-

The Persian Wars (480-478 BCE)

-

The Persian Wars (510-478 B.C.E.)

-

The Ionian Revolt (5l0-494 B.C.E.)

-

Athens alone (494-490 B.C.E.)

-

Xerxes' invasion (480-478 B.C.E.)

-

Formation of the Delian League

-

-

The Decline & Fall of The Greek Polis (431-336 BCE)

-

Economic and military changes

-

Continuing warfare after the Peloponnesian War (404-355 B.C.E.)

-

The rise of Macedon (355-336 B.C.E.)

-

-

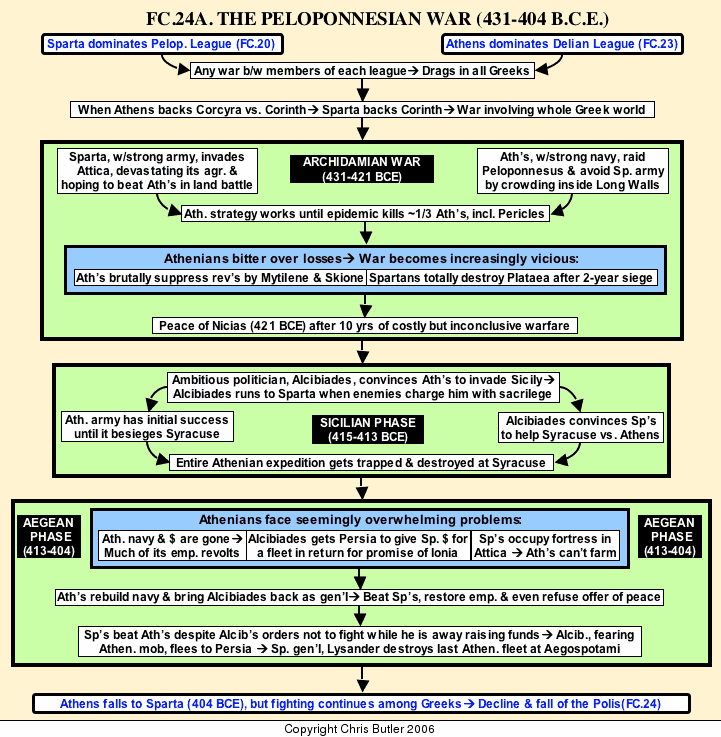

The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE)

-

Disaster and Collapse (421-404 B.C.E.)

-

The Sicilian Expedition

-

Athens' comeback and final fall (413-404 B.C.E.)

-

-

Alexander The Great and The Hellenistic Era (336 BCE-31 BCE)

-

Alexander the Great (336-323 B.C.E.)

-

Alexander's successors and the establishment of a new order (323-c.275B.C.E.)

-

Hellenistic accomplshments

-

Conclusion

-

-

-

-

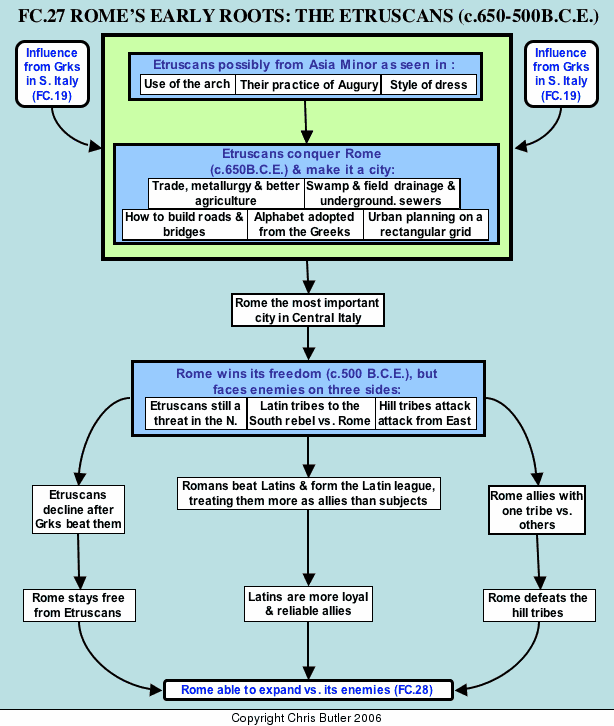

The Impact of Geography On Ancient Italy

-

Introduction

-

Geopolitics

-

-

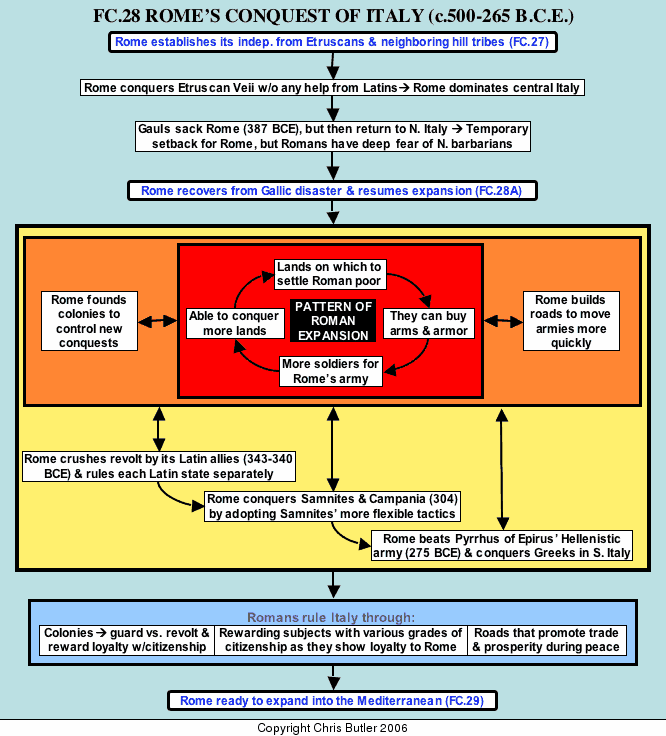

The Roman Conquest of Italy (c.500-265 BCE)

-

Rome's pattern of conquest

-

Rome's campaigns of conquest (387-265 B.C.E.)

-

-

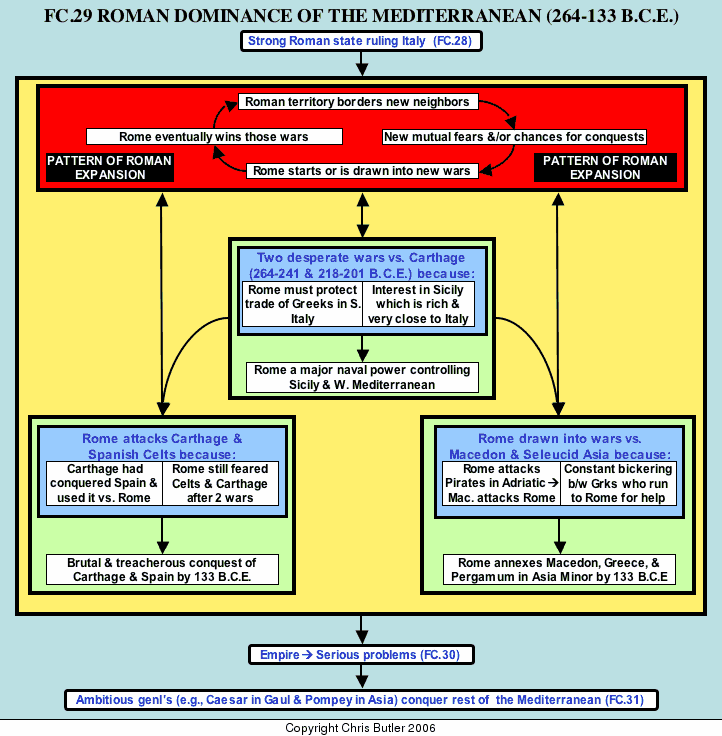

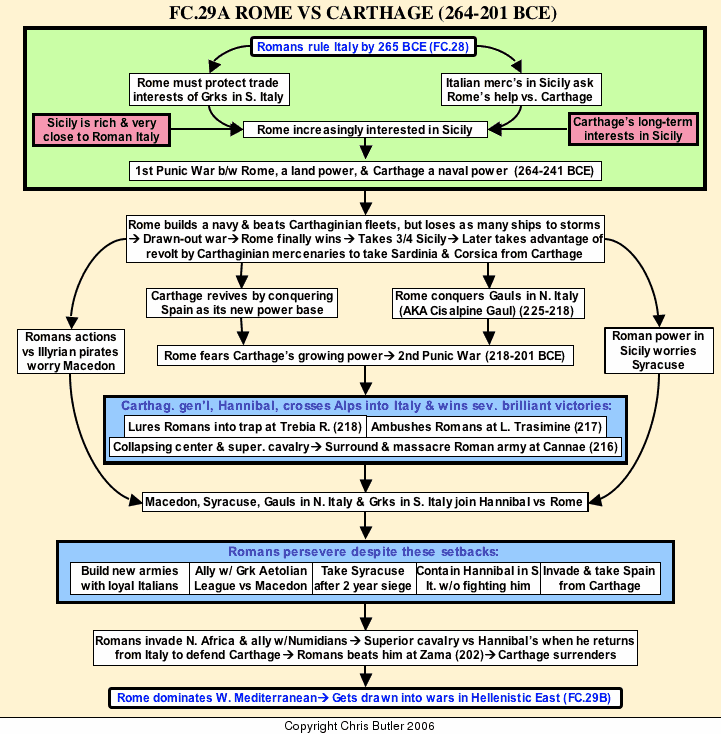

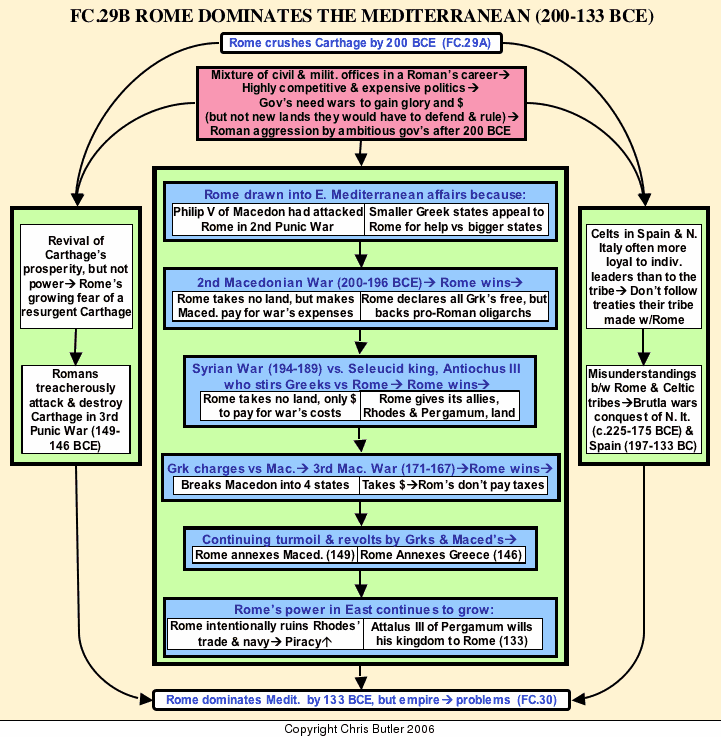

Rome Versus Carthage: The Punic Wars (264-201 BCE)

-

The First Punic War(264-241 B.C.E.)

-

Between the wars

-

The Second Punic War (218-201 BCE)

-

-

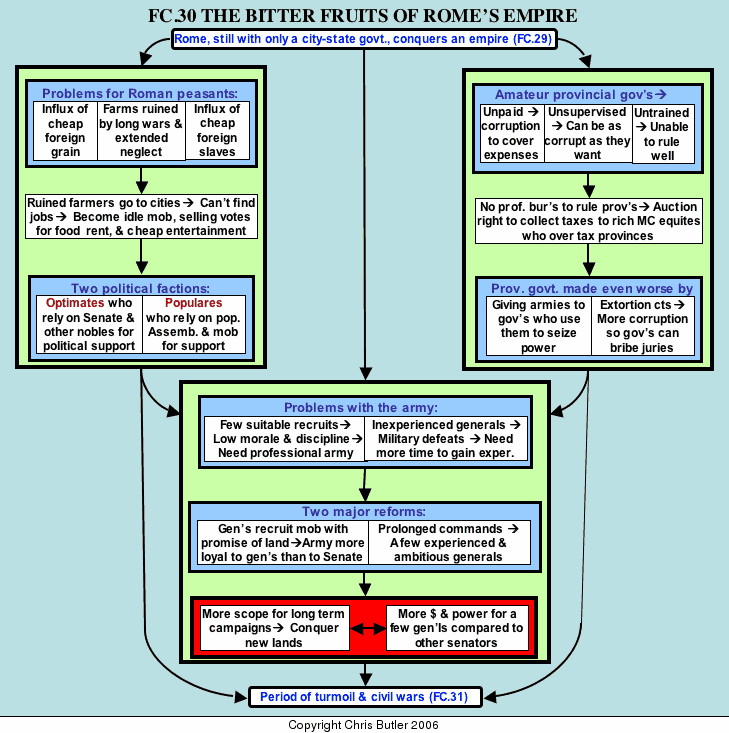

The Fall of The Roman Republic (133-31 BCE)

-

Pattern of decline

-

First attempts at reform: the Gracchi

-

Marius and the Roman army

-

Sulla and the First Civil War

-

The rise of Julius Caesar

-

Octavian, Antony, and two more civil wars (44-31 B.C.E.)

-

-

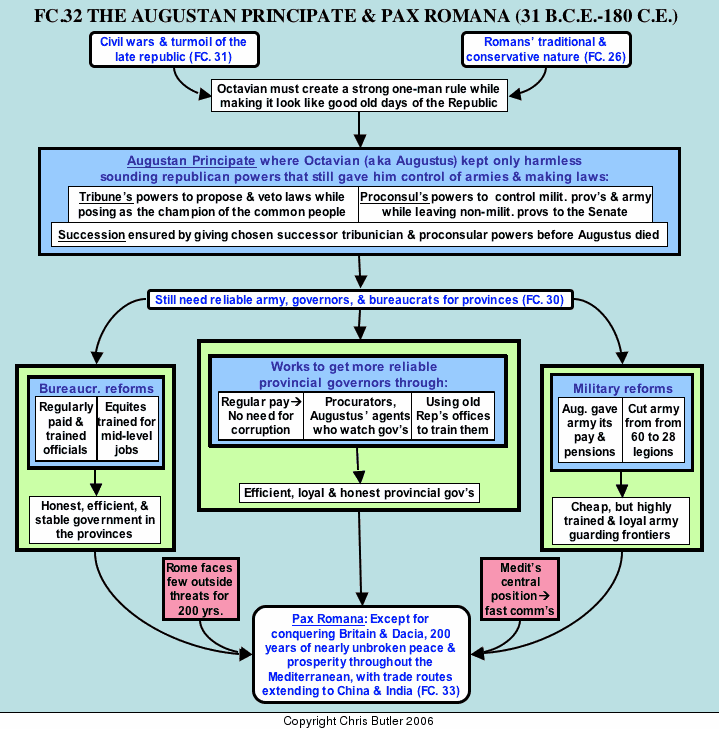

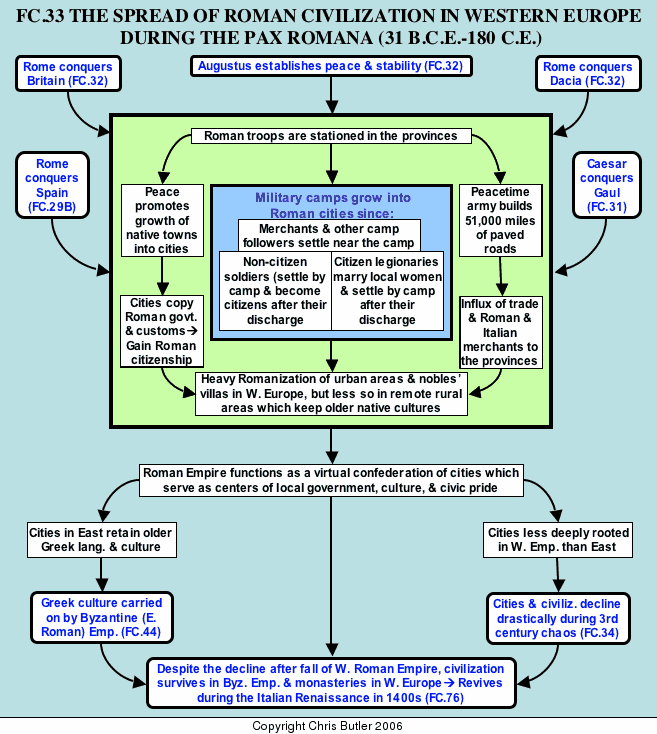

The Augustan Principate (31 BCE-160 CE)

-

The Empire after Augustus

-

-

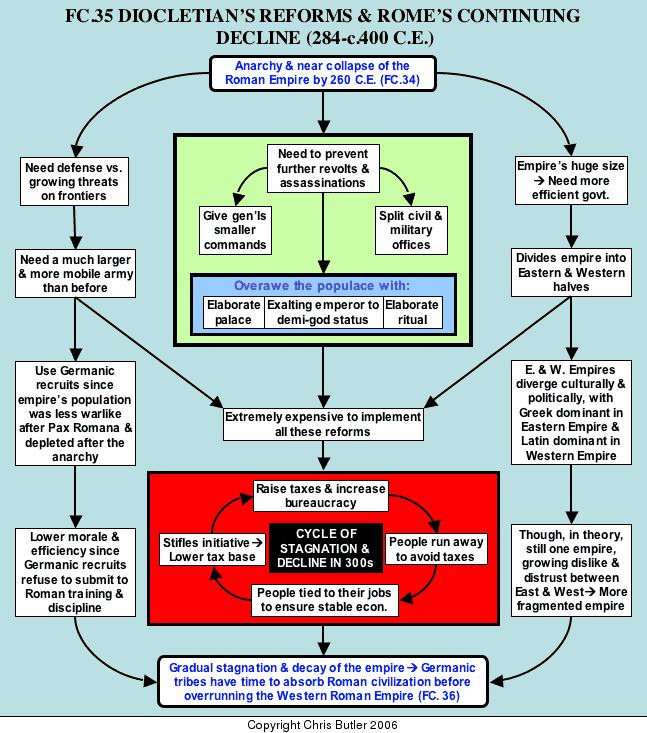

The Near Collapse of The Roman Empire (160-284 CE)

-

Mounting problems (161-235 C.E.)

-

The third century anarchy (235-284 C.E.)

-

-

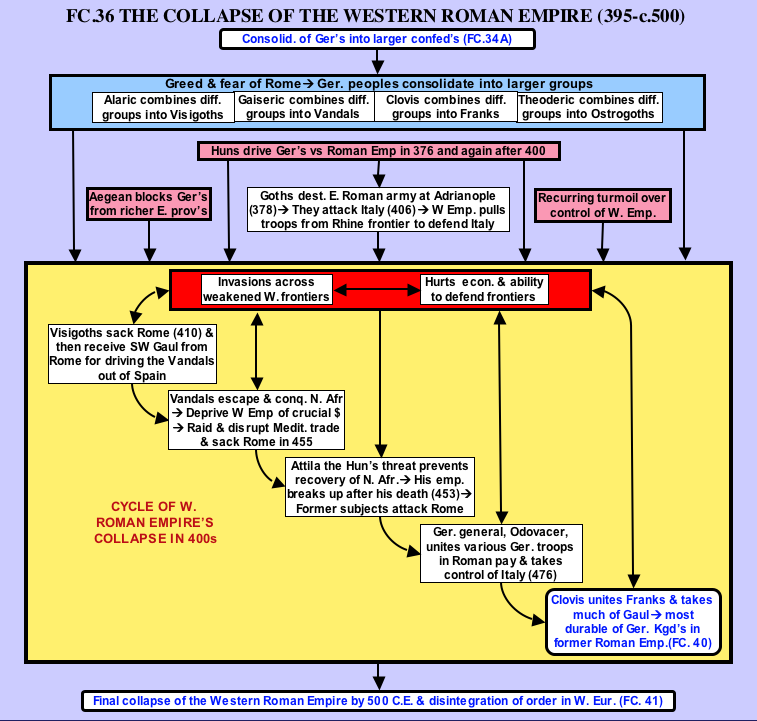

The Collapse of The Western Roman Empire (395-c.500)

-

Why the West?

-

How and why the barbarians took over

-

-

-

-

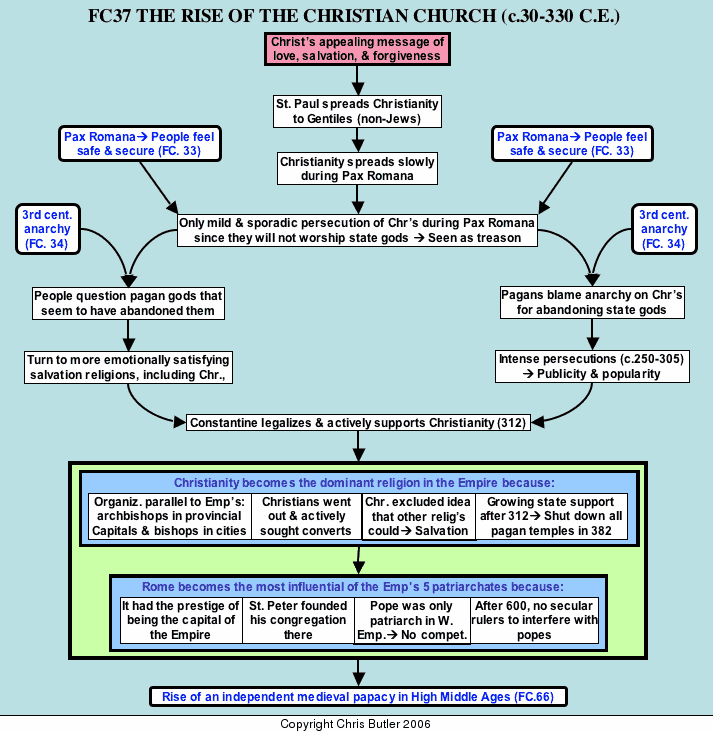

The Rise of The Christian Church To c.300 CE

-

Early history (c.30-3ll C.E.)

-

The great persecutions

-

Constantine and triumph of the Church

-

-

The Impact of The Church's Triumph (c.300-500)

-

Religious disputes and heresies

-

Poverty, chastity, and obedience: the rise of monasteries

-

-

The Mediterranean's Transition To The Middle Ages

-

Introduction: the “Dark Ages”

-

Converging interests

-

Justinian and the reconquest of Italy

-

A gradual transition

-

-

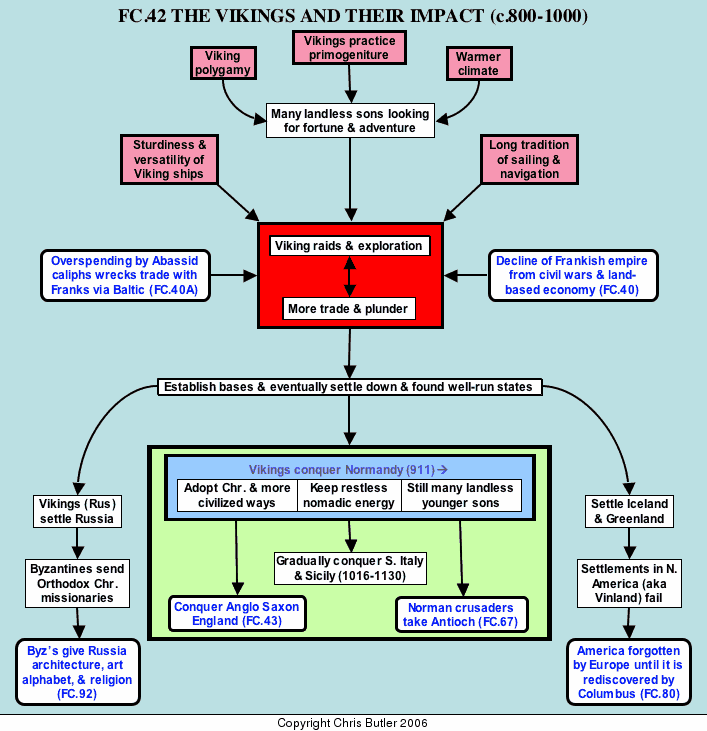

The Rise of The Franks (c.500-841)

-

Charlemagne (768-8l4)

-

The disintegration of the Carolingian order (8l4-c.1000)

-

-

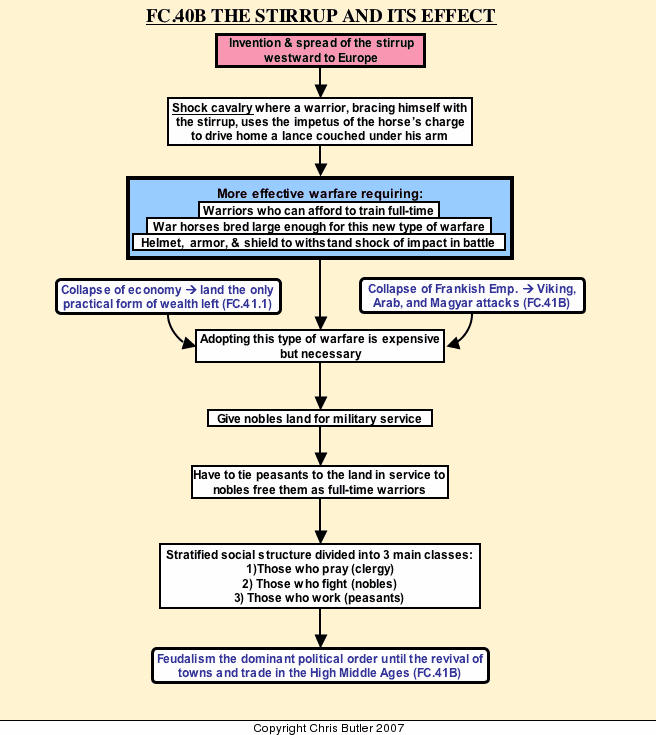

The Collapse of Order & Rise of Feudalism In W. Europe

-

Feudalism

-

-

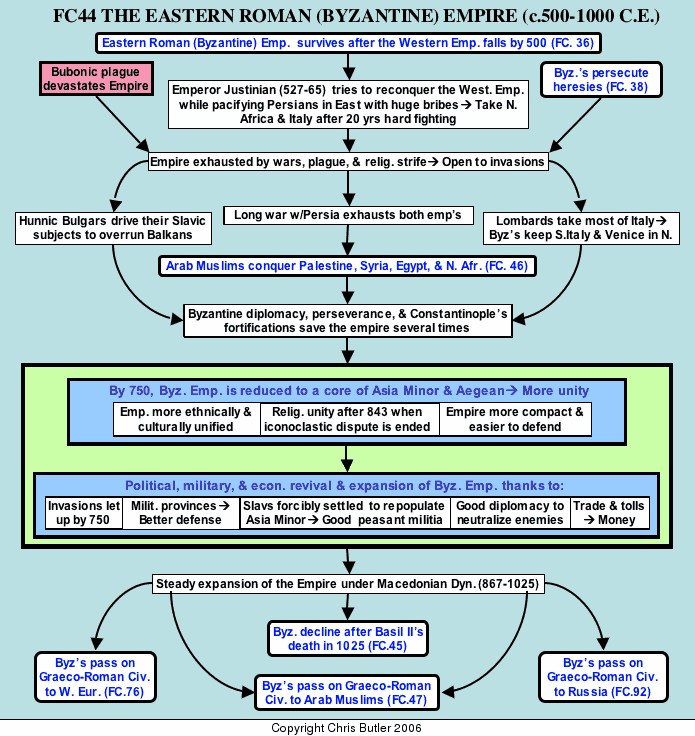

The Byzantine Empire (c.500-1025)

-

Introduction: the "Second Rome"

-

Turmoil, crisis, and the transition from Roman to Byzantine Empire (527-7l7 C.E.)

-

The imperial centuries (c.750-1025)

-

Our debt to the Byzantines

-

-

-

-

Classical Asia to c.1800 C.E.: Islam, India, China, and Japan

-

-

The Rise of The Arabs & Islamic Civilization (632-c.1000)

-

The sweep of Empire (632-750 C.E.)

-

Adapting to empire

-

The ruler

-

Ruling the empire

-

The development of Islamic Civilization

-

-

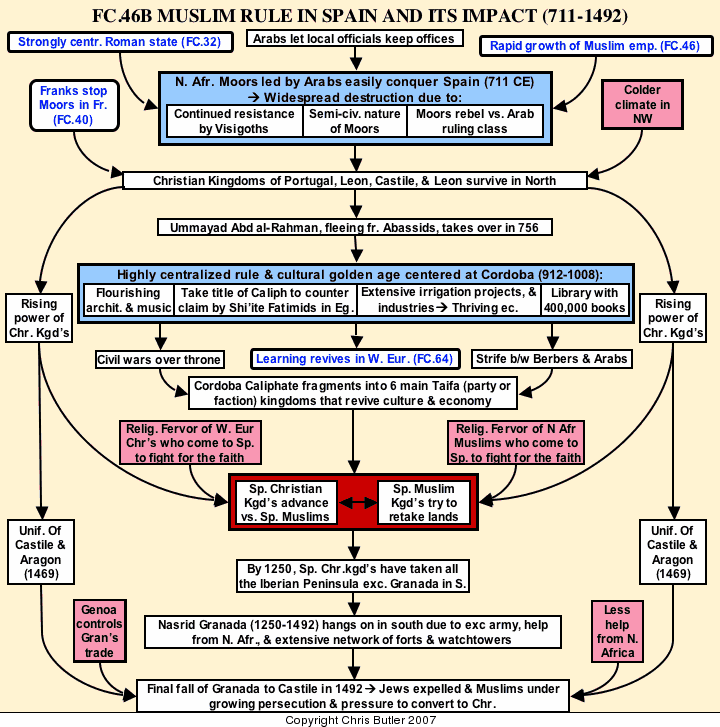

Muslim Civilization In Spain (711-1492)

-

The coming of the Moors

-

The Ummayad Caliphate of Cordoba (c.800- 1008)

-

Fall of the Caliphate of Cordoba and rise of the Taifa, or "Party kings" (1008-c.1080)

-

Islamic resurgence from North Africa: the Amoravids & Almohads (1080-1250)

-

Nasrid Granada and the end of Moorish power in Spain (c.1250-1492)

-

Moorish Spain's legacy

-

-

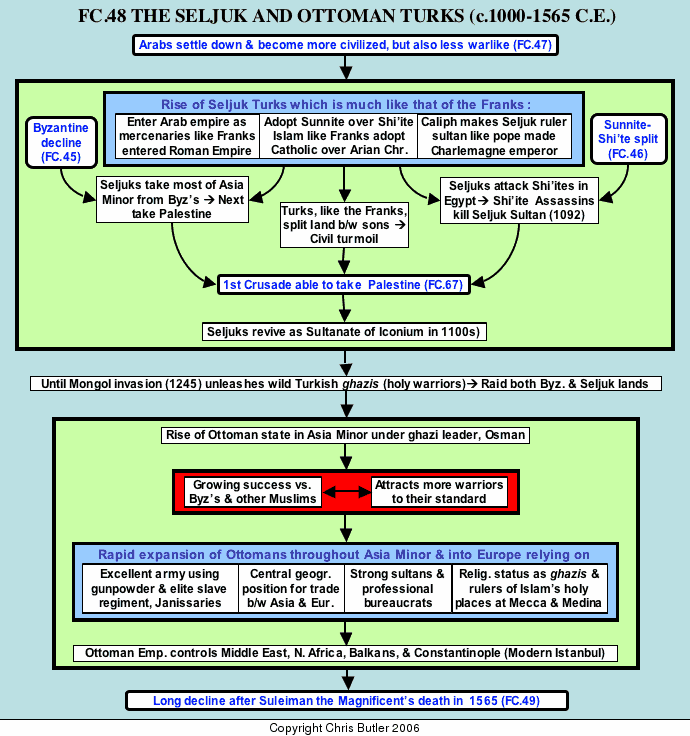

The Rise of The Seljuk & Ottoman Turks (c.1000-1565)

-

The Seljuk Turks

-

Rise of the Ottoman Turks

-

-

-

Indian History and Civilization

-

The Development of Indian Civilization (1500-500 BCE)

-

Aryan society and the Vedic Age (c.1500-1000 B.C.E.)

-

The Later Vedic Age (c.1000-500 B.C.E.)

-

Caste

-

The evolution of India's religious ideas

-

Jainism and Buddhism

-

-

India From The Maurya To The Gupta Dynasties (500 BCE-711 CE)

-

The Mauryan Empire (c.325-200 B.C.E.)

-

The Kushans (78-c.300 C.E.)

-

Mahayana and Hinyana Buddhism

-

The Guptas (c.300-500)

-

Hinduism

-

-

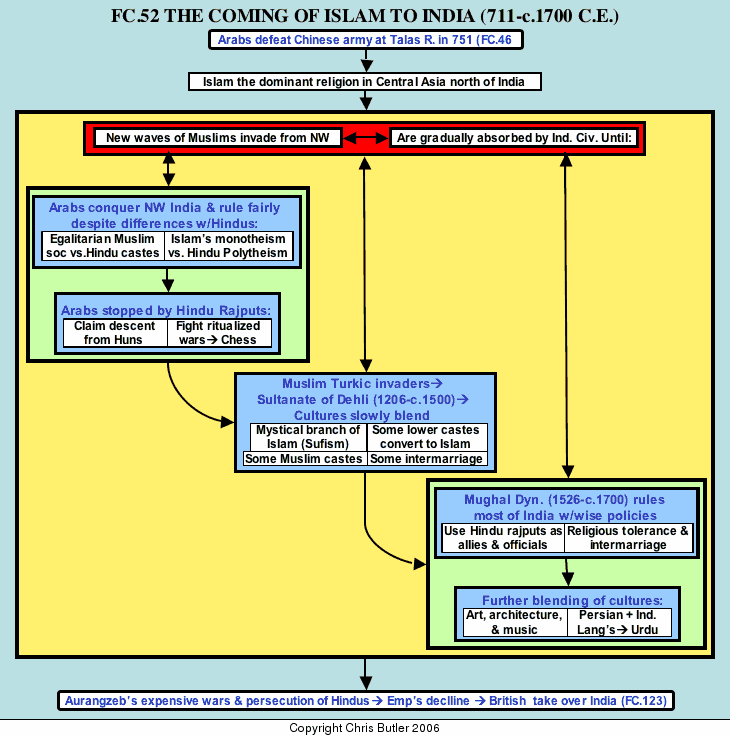

The Coming of Islam To India (711-c.1800)

-

Introduction

-

Pattern of development

-

Arabs and Rajputs (711-c.1000 C.E.)

-

Turkish invaders and the Sultanate of Delhi (c.1000-1526)

-

Decline of the Mughals

-

-

-

-

Early China (1500-221 BCE) and The Recurring Pattern of Chinese History

-

The geographic factor

-

The Shang Dynasty (c.1500-1028 B.C.E.)

-

The pattern of Chinese history

-

The Zhou Dynasty (1028-256 B.C.E.)

-

Confucianism and Taoism

-

-

The Qin and Han Dynasties (221 BCE-220 CE

-

The Later Zhou (772-221 B.C.E.)

-

Qin Dynasty (256-202 B.C.E.)

-

The Han Dynasty (202 B.C.E.-220 C.E.)

-

-

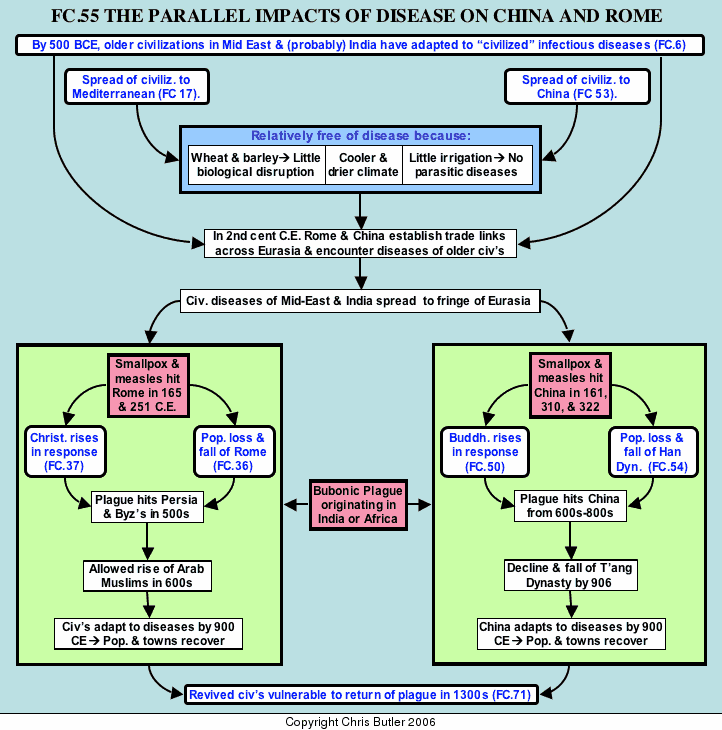

The Parallel Impacts of Disease On Chinese and Roman History

-

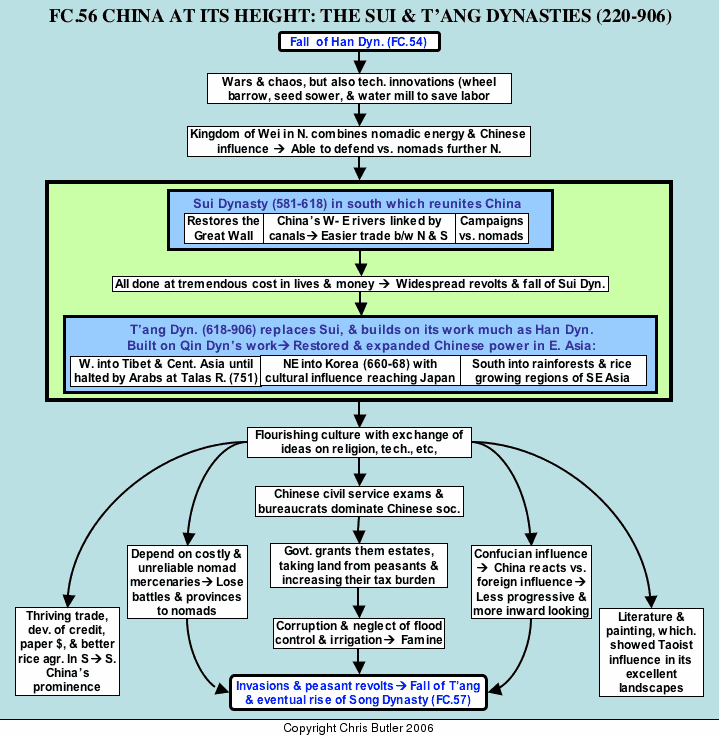

The Sui and T'ang Dynasties (220-906 CE)

-

The Six Dynasties Period (220-581 C.E.)

-

The Sui Dynasty (581-618)

-

The T'ang Dynasty (618-906)

-

Fall of the T'ang Dynasty

-

-

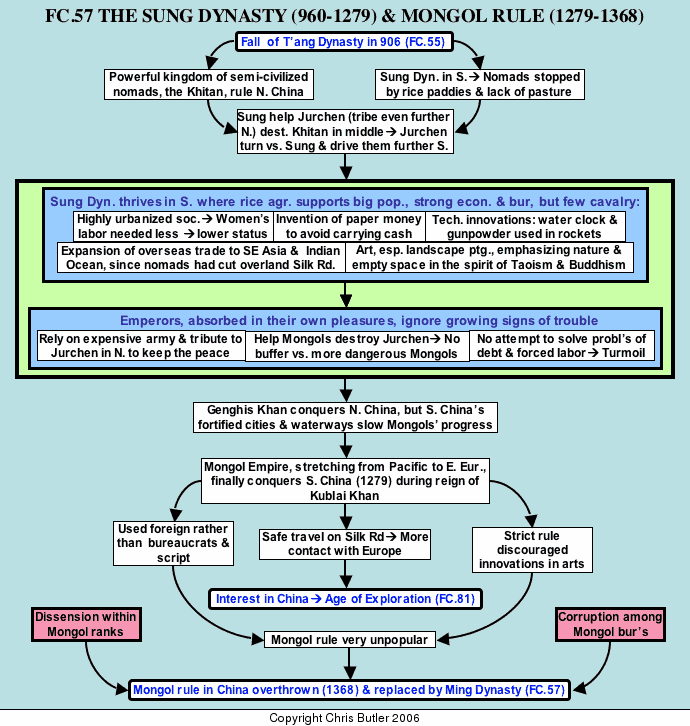

The Sung & Mongol Dynasties (906-1368)

-

The Mongol Empire (1279-1368)

-

-

The Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368-c.1800)

-

The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644)

-

The Qing Dynasty (1644-1911)

-

-

-

The Rise of Japanese Civilization

-

The Development of Early Japan To c.700 CE

-

Introduction: the geographic element

-

Early elements of Japanese culture

-

Growing Chinese influence

-

The Taika reforms and rise of the Japanese state

-

-

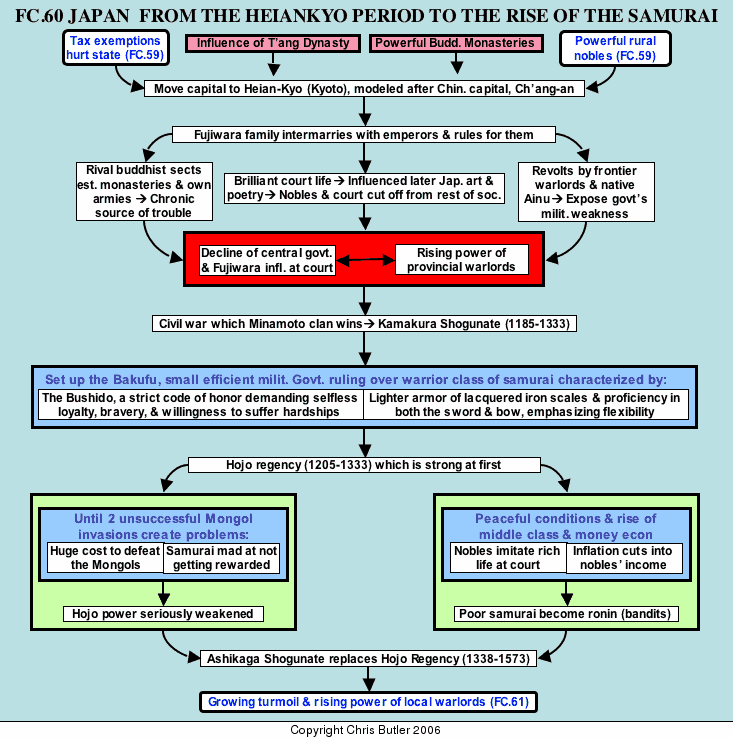

Japan's Heian & Samurai Eras (c.700-1338)

-

Heiankyo and Japanese court society (794-1184)

-

The Kamakura Shogunate and rise of the samurai (1185-1333)

-

-

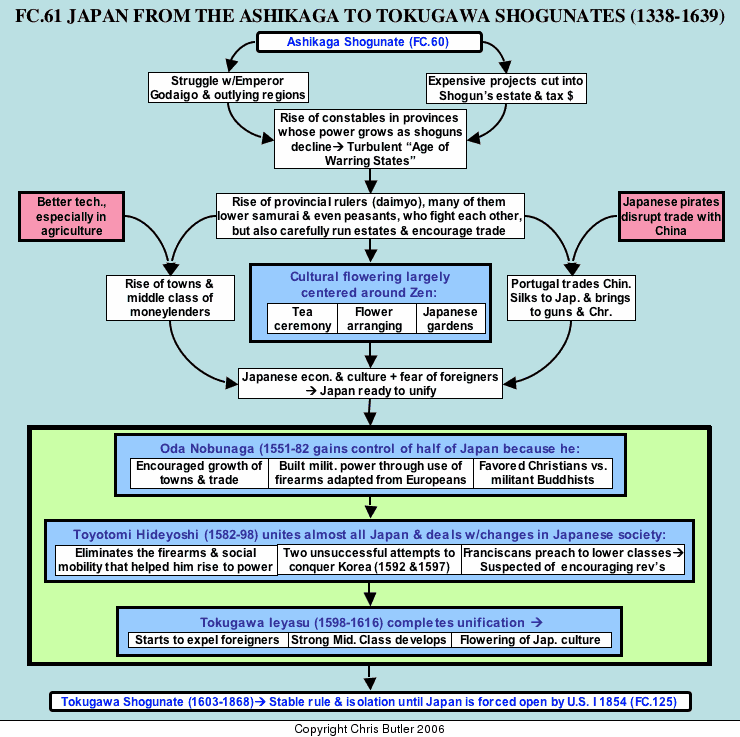

Civil War & Reunification By The Tokugawa Dynasty (1338-1639)

-

The breakdown of centralized rule and rise of the Daimyo

-

Zen Buddhism

-

The restoration of order and unity by Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1551-98)

-

-

-

-

Revival of the West c.1000-1500 C.E.

-

The High and Later Middle Ages in Europe

-

The Agricultural Revolution In Medieval Europe

-

Europe (c.1000 C.E.)

-

First stirrings of revival

-

An agricultural revolution

-

-

The Rise of Towns In Western Europe (c.1000-1300)

-

From trade fairs to towns

-

The impact of towns

-

-

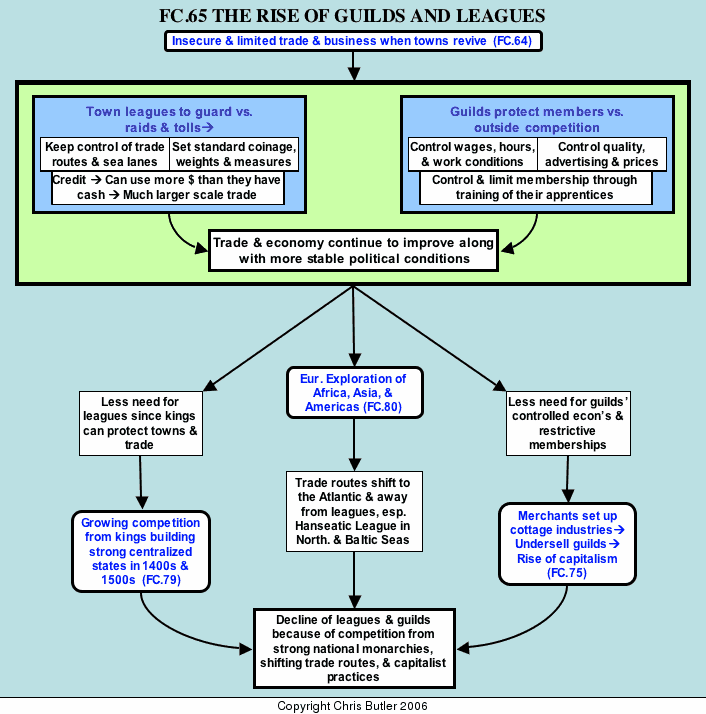

Leagues & Guilds In Western Europe

-

Leagues

-

-

Rise of The Medieval Papacy (c.900-1300)

-

Introduction: the plight of the Church in the Early Middle Ages

-

The zeal for reform (910-1073)

-

The Investiture Struggle (1073-1122)

-

The Papal monarchy at its height (1122-c.1300)

-

-

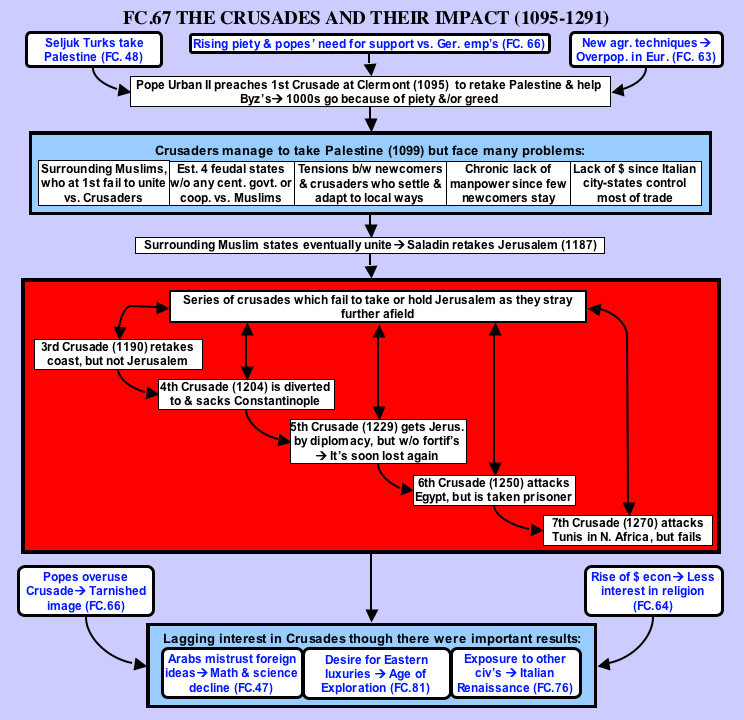

The Crusades & Their Impact (1095-1291)

-

The First Crusade (1095-99)

-

The Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099-1187)

-

-

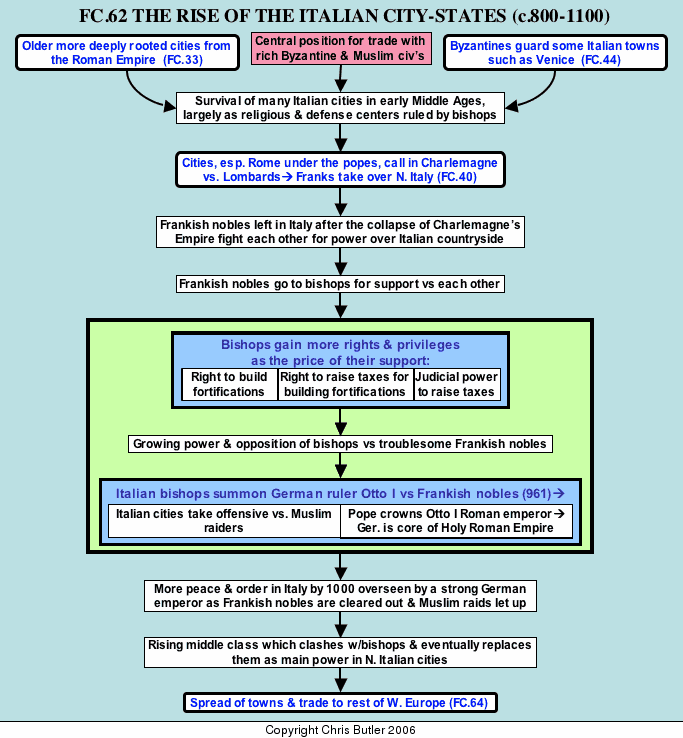

The Holy Roman Empire of Germany (911-c.1500)

-

Introduction

-

The Saxon Dynasty

-

-

The Crisis of The Later Middle Ages (c.1300-1450)

-

Introduction

-

Causes of Stress

-

The Black Death and its results

-

Decline of the Church and nobles

-

Popular uprisings

-

-

The Black Death and Its Effects (1347-c.1450)

-

Origins of the Plague

-

The results of the Black Death

-

Popular uprisings

-

Decline of the Church and nobles

-

-

Schism & Heresies In Late Medieval Europe (1347-c.1450)

-

The Avignon Papacy or "Babylonian Captivity" (1309-77)

-

The Great Schism and Conciliar movement

-

The challenge from below: the Lollard and Hussite heresies

-

-

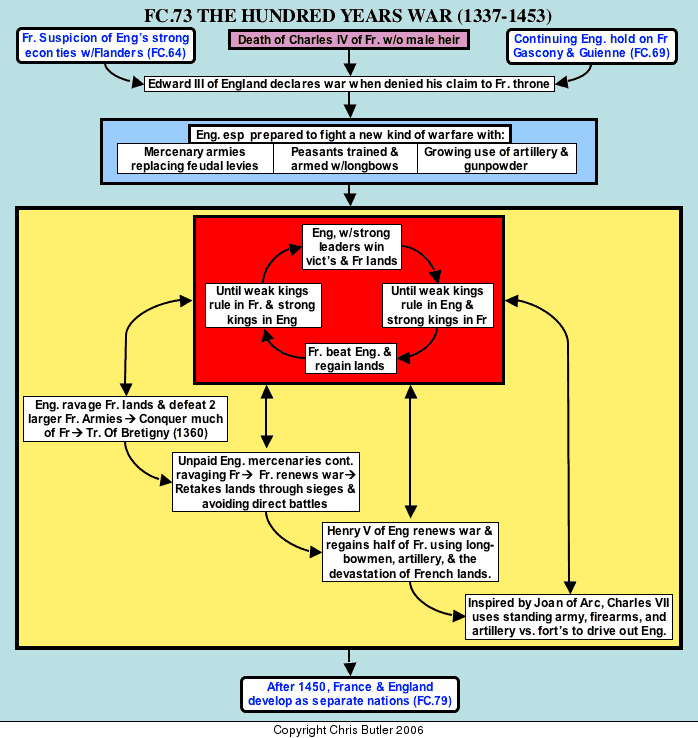

The Hundred Years War (1337-1453)

-

Introduction

-

Causes

-

The new face of war

-

Phase I: England ascendant 1337-1369)

-

Phase II: The French resurgence (1369-1413)

-

The English resurgence (1413-1428)

-

Joan of Arc and the final French triumph (1428-53)

-

Conclusion

-

-

-

The Invention of The Printing Press and Its Effects

-

Introduction

-

The impact of the printing press

-

-

The Economic Recovery of Europe (c.1450-1600)

-

Social changes

-

New business techniques

-

-

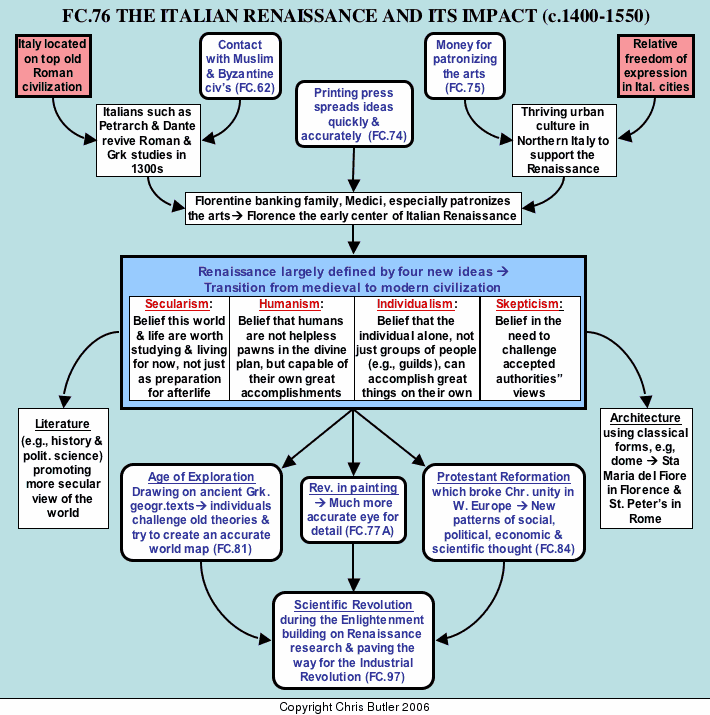

The Italian Renaissance (c.1400-1550)

-

Introduction: why Italy?

-

New patterns of thought

-

-

The Revolution In Renaissance Painting

-

Introduction

-

Materials used

-

New techniques

-

-

The Northern Renaissance (c.1500-1600)

-

Introduction

-

Reconciling religion and the Renaissance

-

The emerging national cultures in the Northern Renaissance

-

Results of the Northern Renaissance

-

-

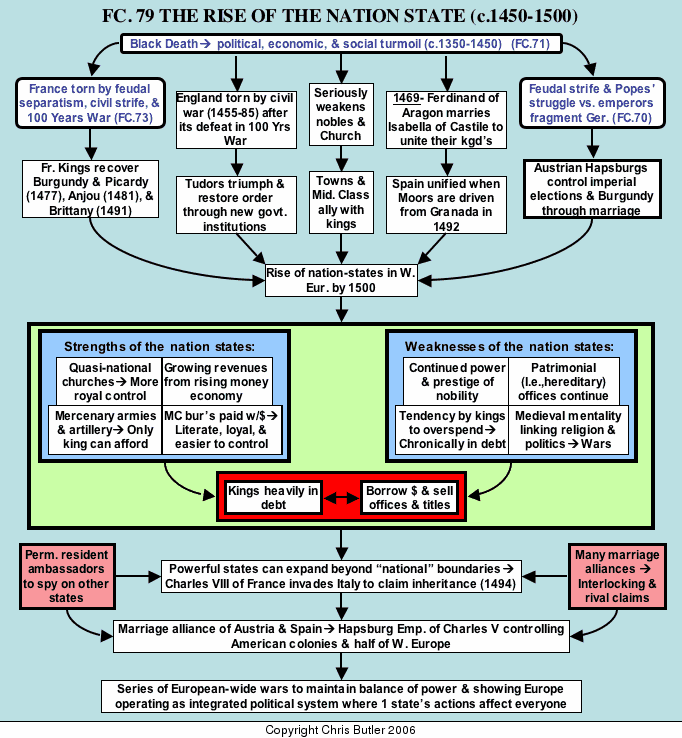

He Rise of The Nation State During The Renaissance

-

Finances

-

The new warfare

-

Limits to the Renaissance state's power

-

The "New Diplomacy"

-

-

-

The Age of Exploration (c.1400-1900)

-

Geopolitical Factors In The Rise of Europe

-

Introduction

-

Europe's geography and its effects

-

-

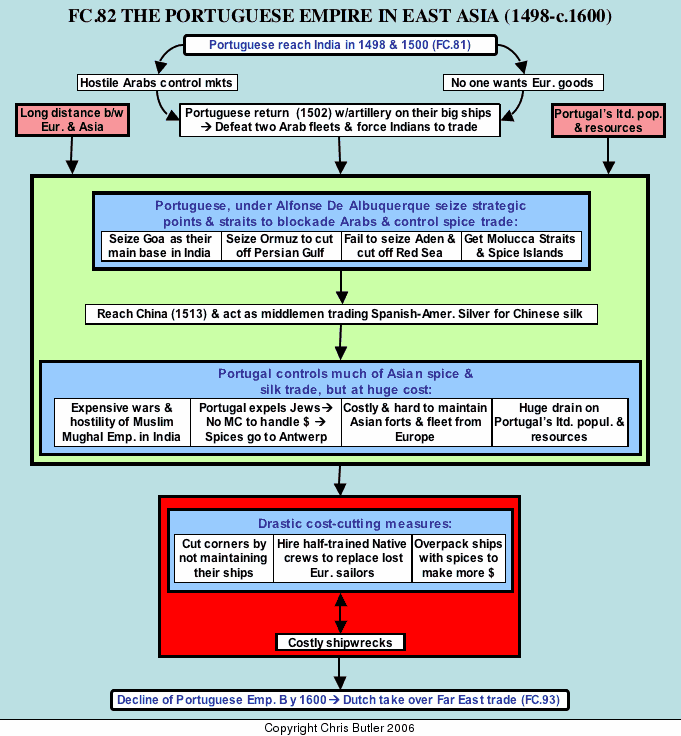

Early Voyages of Exploration (c.1400-1550)

-

Introduction

-

Factors favoring Europe

-

Portugal and the East (c.1400-1498)

-

Spain and the exploration of the West (1492-c.1550)

-

Interior and coastal explorations (1519-c.1550)

-

-

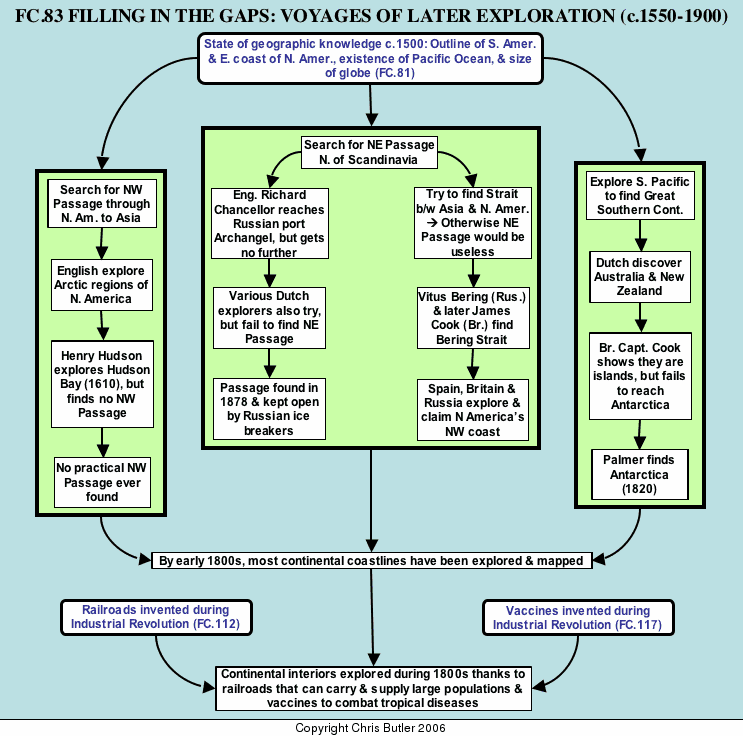

The Later Voyages of Exploration (c.1550-1900)

-

Conclusion

-

-

-

The Age of Reformation and religious wars (1517-1648)

-

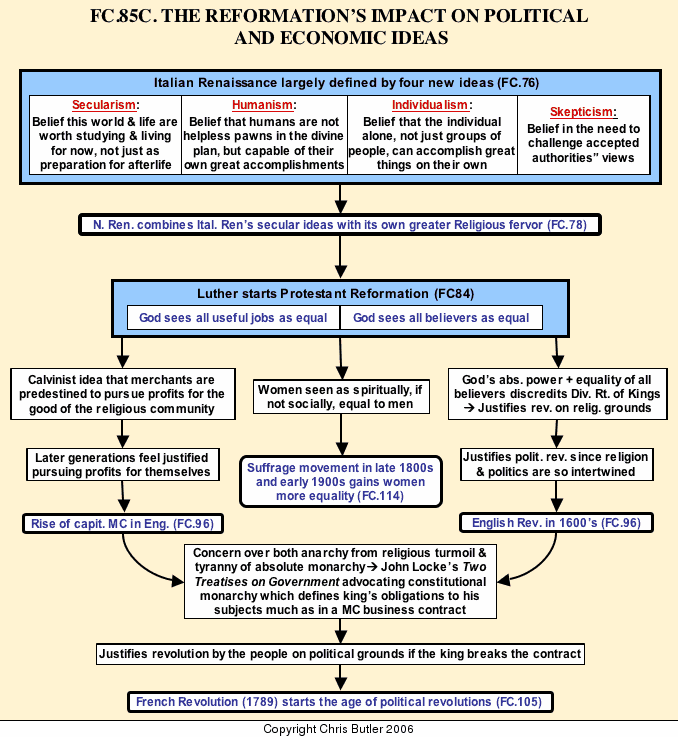

The Roots and Birth of The Protestant Reformation

-

The storm breaks

-

Luther’s religion

-

The spread of Lutheranism

-

Luther’s achievement

-

-

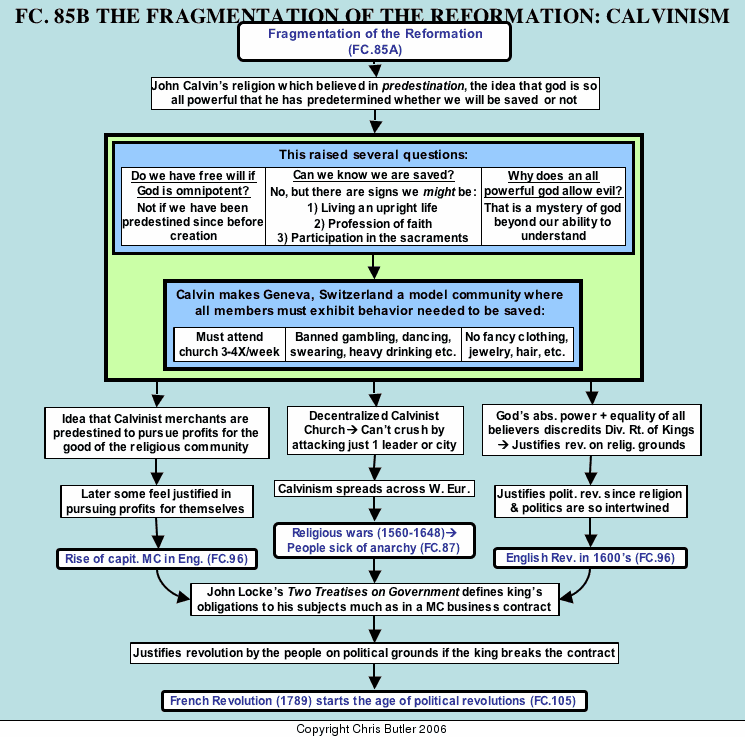

The Reformation Fragments II: Calvinism

-

Introduction

-

Calvin's religion

-

Long range effects of Calvinism

-

-

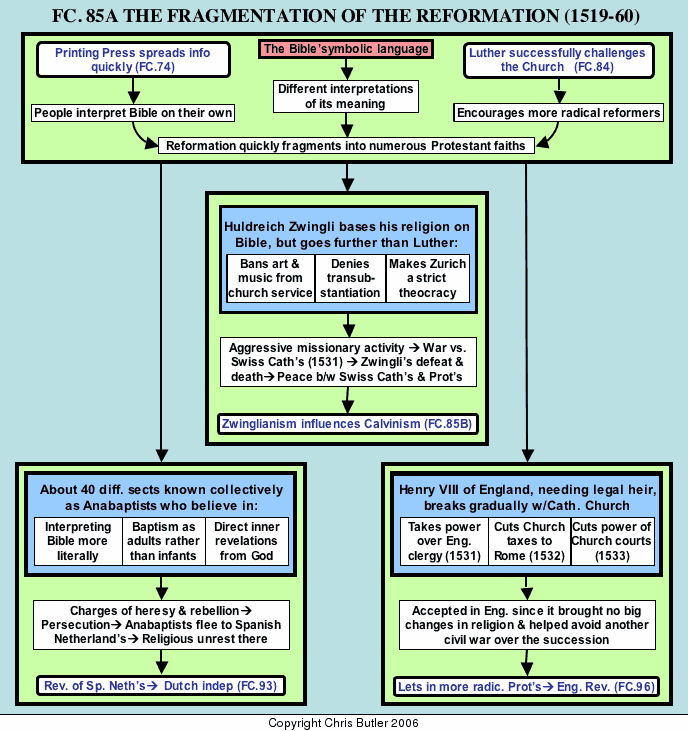

The Reformation Fragments I: Zwinglianism &Anabaptism

-

Introduction

-

Huldreich Zwingli and the Swiss Reformation

-

Grassroots Protestantism: the Anabaptists

-

The English Reformation

-

-

-

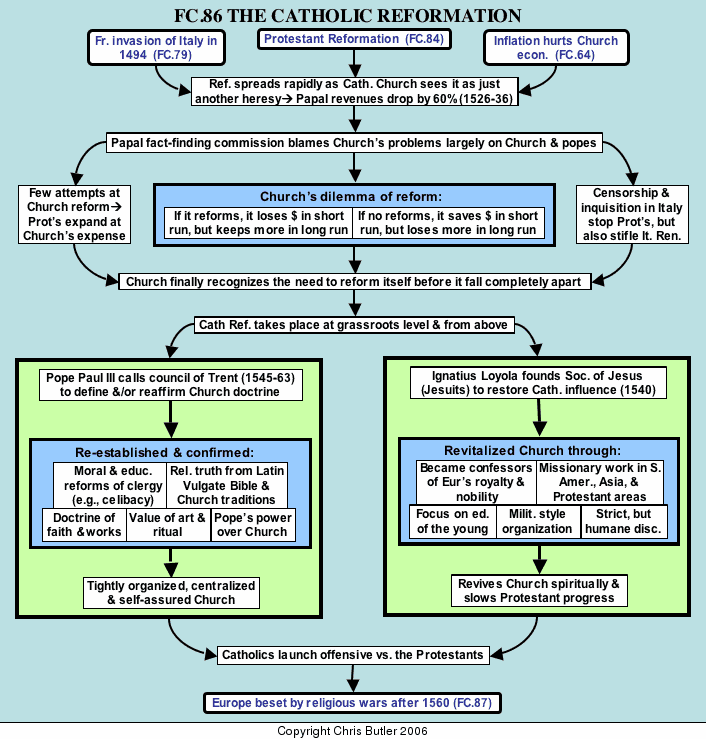

Early reactions by the Church to Protestantism

-

Reform from the top: the Council of Trent (1543-63)

-

Reform from below: Ignatius Loyola and the Jesuits

-

-

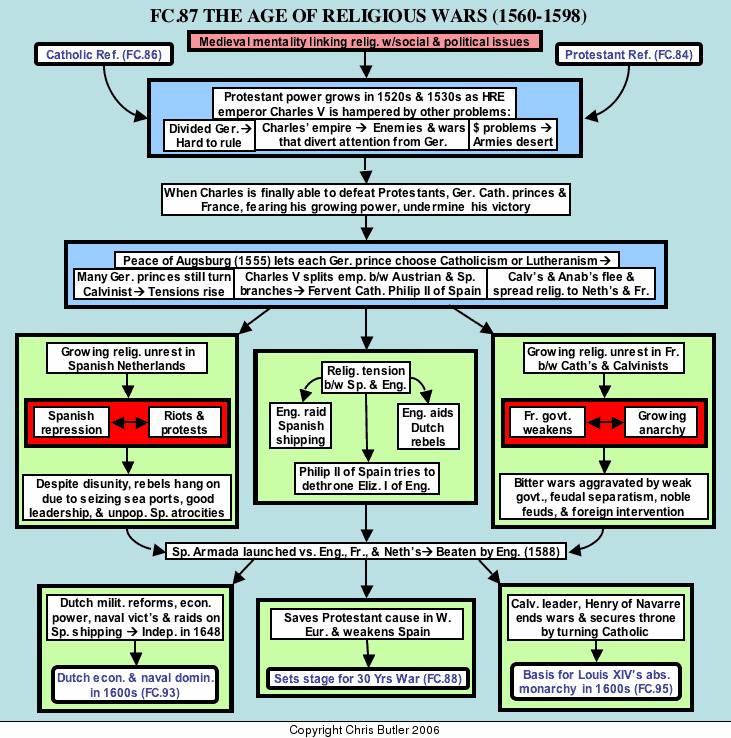

The Age of Religious Wars (c.1560-98)

-

Germany (1521-55)

-

Revolt of the Spanish Netherlands (1566-1648)

-

The French Wars of Religion (1562-98)

-

Elizabethan England and the Spanish Armada

-

-

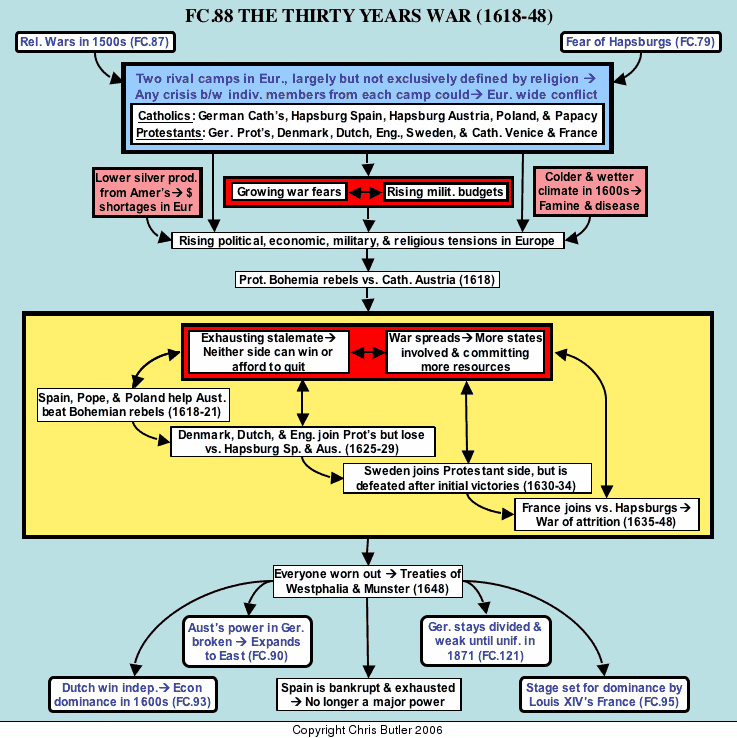

An Overview of The Thirty Years War (1618-48)

-

Introduction

-

Causes and outbreak of war

-

-

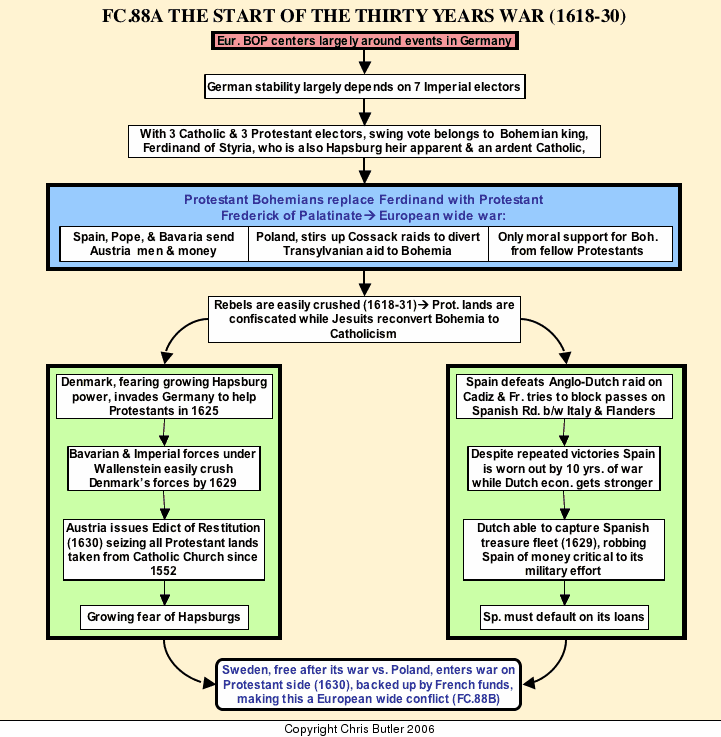

The Early Stages of The Thirty Years War (1618-31)

-

Opening phases of the war (1618-35)

-

-

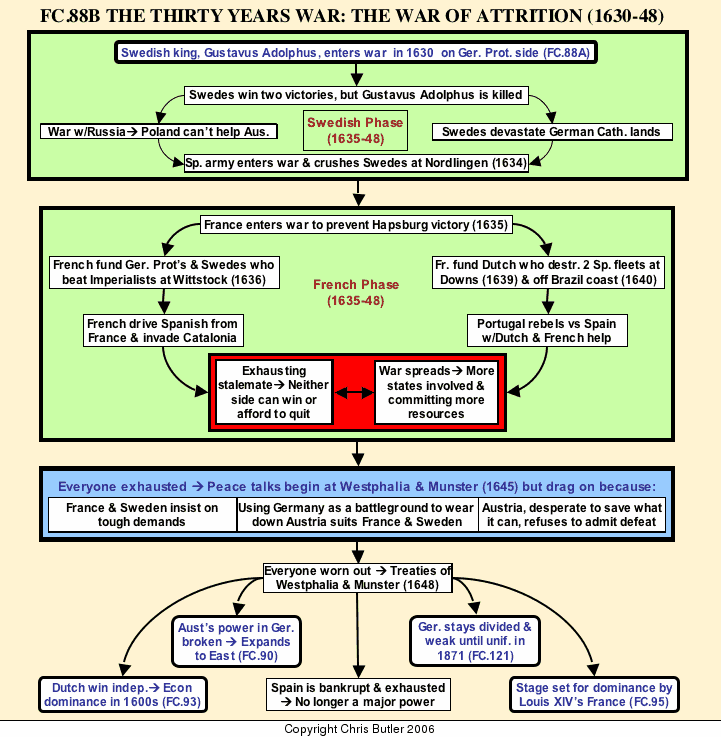

The Later Stages of The 30 Years War (1631-48)

-

The Swedish Phase

-

The war of attrition (1635-48)

-

End of the war and its results

-

-

-

The rise of absolute monarchies in Eastern and Western Europe (c.1600-1700)

-

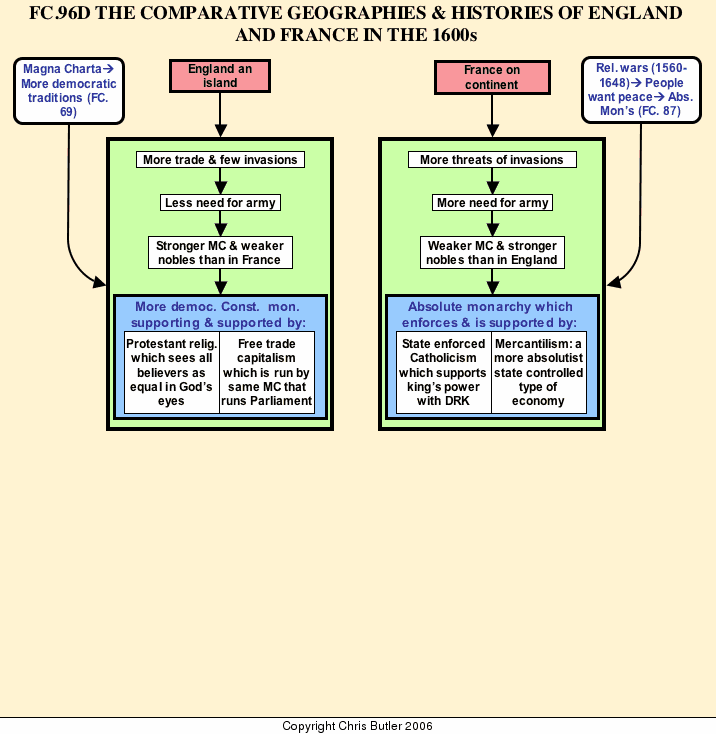

The Comparative Geographies and Histories of Eastern and Western Europe

-

Between East and West

-

-

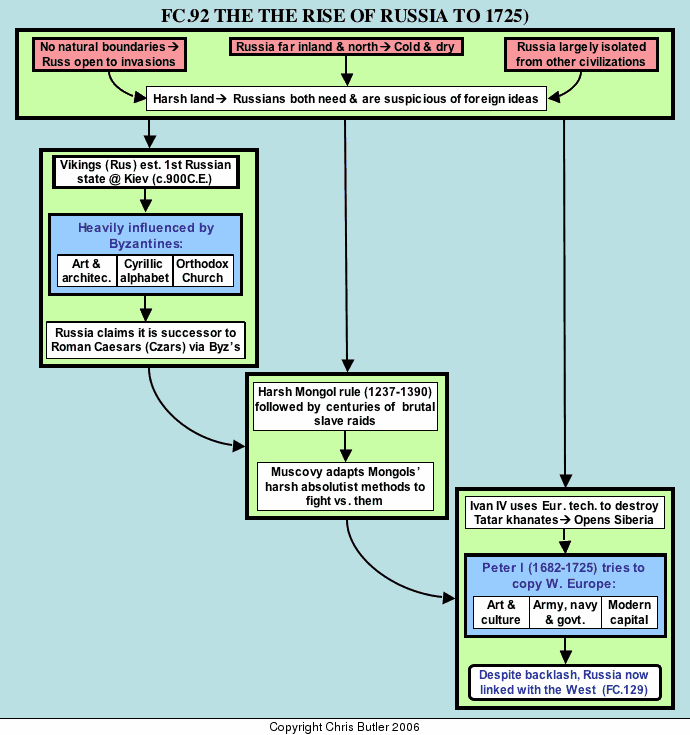

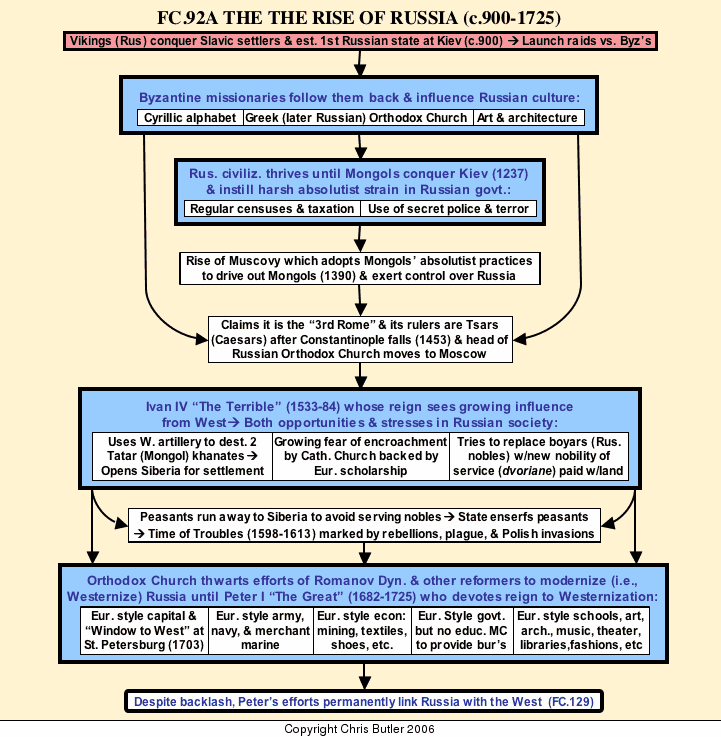

The Early History of Russia To 1725

-

Early history

-

Muscovy

-

The “Time of Troubles”

-

-

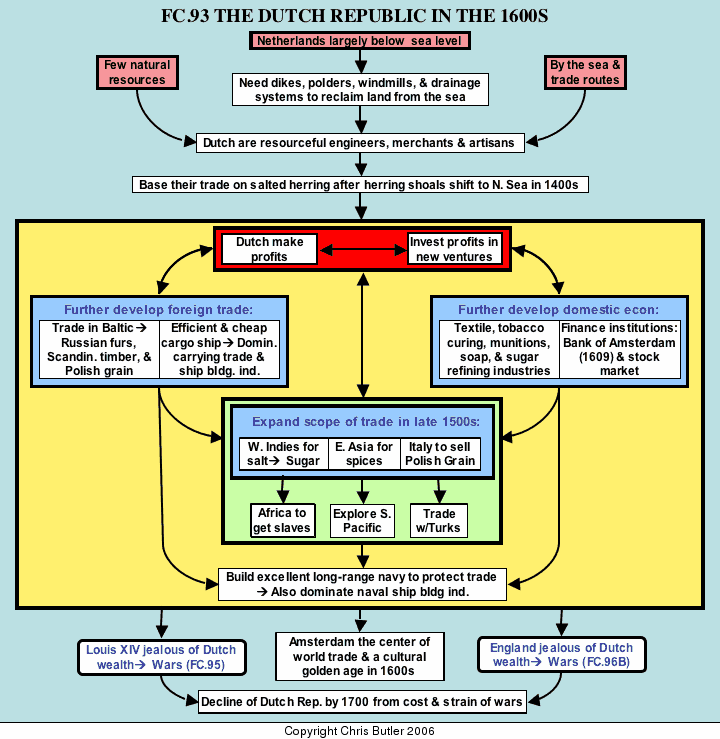

The Rise of The Dutch Republic In The 1600's

-

Introduction

-

Geography of the Netherlands

-

The Dutch pattern of growth

-

A cultural golden age

-

Conclusion

-

-

-

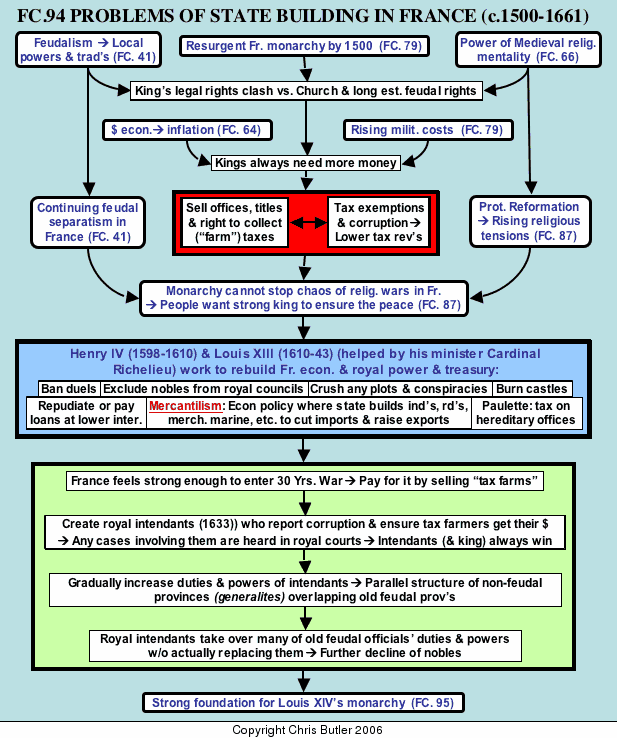

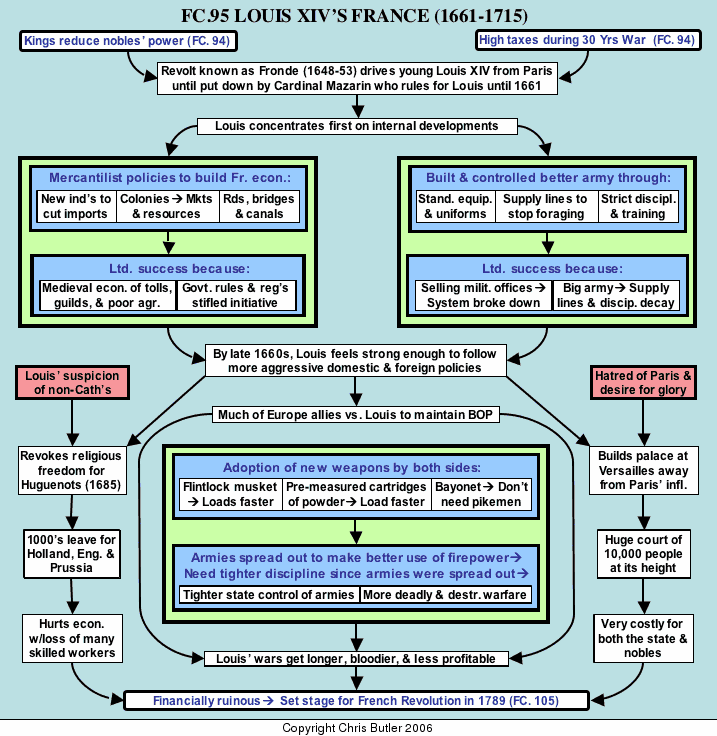

Introduction

-

Louis' early life and reign (1643-61)

-

Louis' internal policies

-

Versailles

-

Louis' diplomacy and wars

-

Results of Louis' reign

-

-

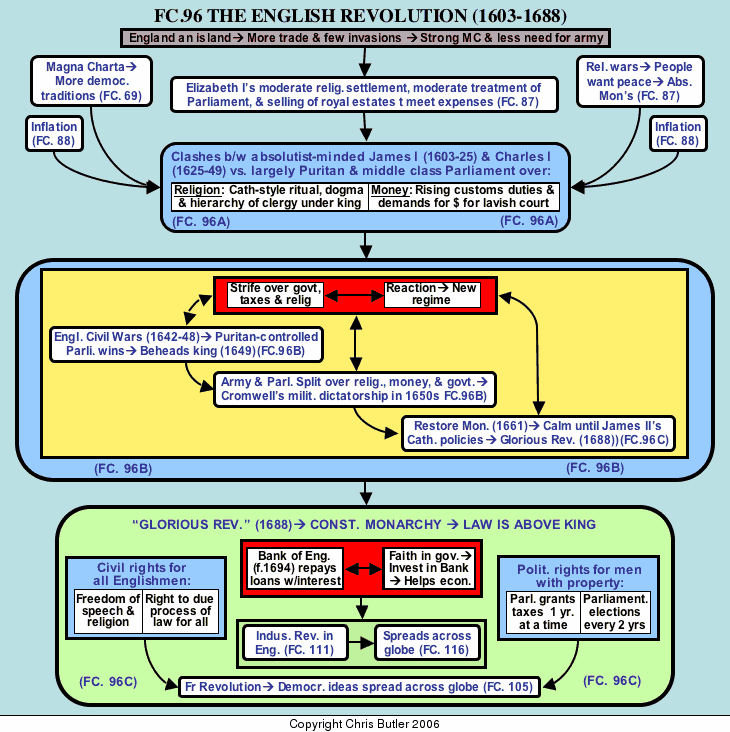

The English Revolution: (1603-88)

-

Introduction: a century of change

-

Background to the Revolution

-

Pattern of events (1625-88)

-

-

James I, Charles I, and The Road To The English Civil War (1603-1642)

-

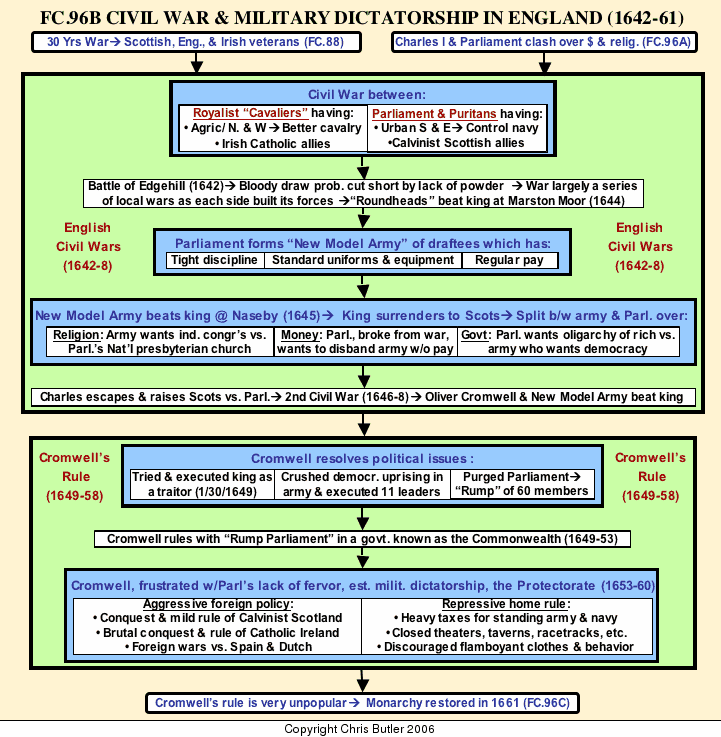

The English Revolution: From Civil War To Military Dictatorship (1642-60)

-

The English Civil War (1642-45)

-

More bickering and a second civil war (1645-1648)

-

Cromwell's Dictatorship (1649-60)

-

-

The English Revolution From The Restoration Monarchy To The Glorious Revolution (1660-1688)

-

Charles II and the Restoration Monarchy (1660-85)

-

James II and the Glorious Revolution (1685-88)

-

Results of the English Revolution

-

-

-

-

The Rise of The Modern State In Enlightenment Europe

-

Introduction

-

Russia

-

-

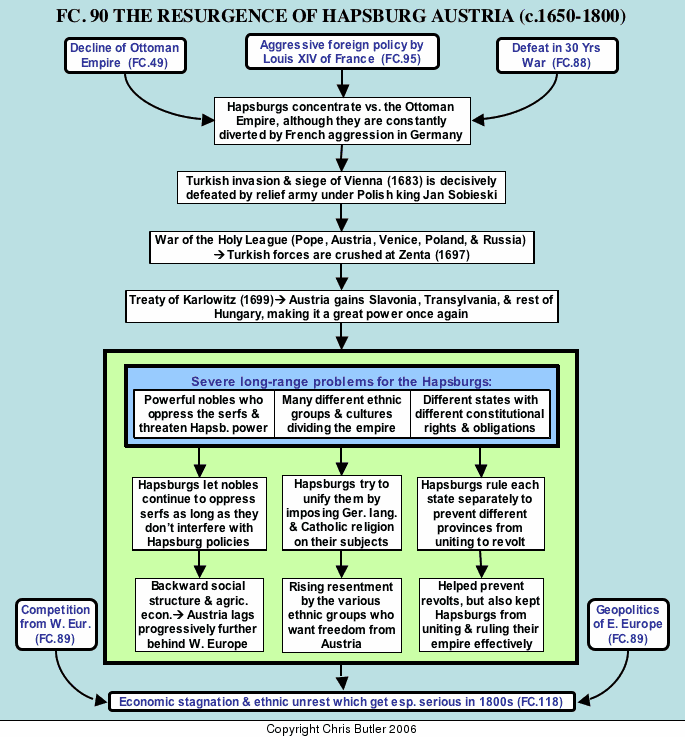

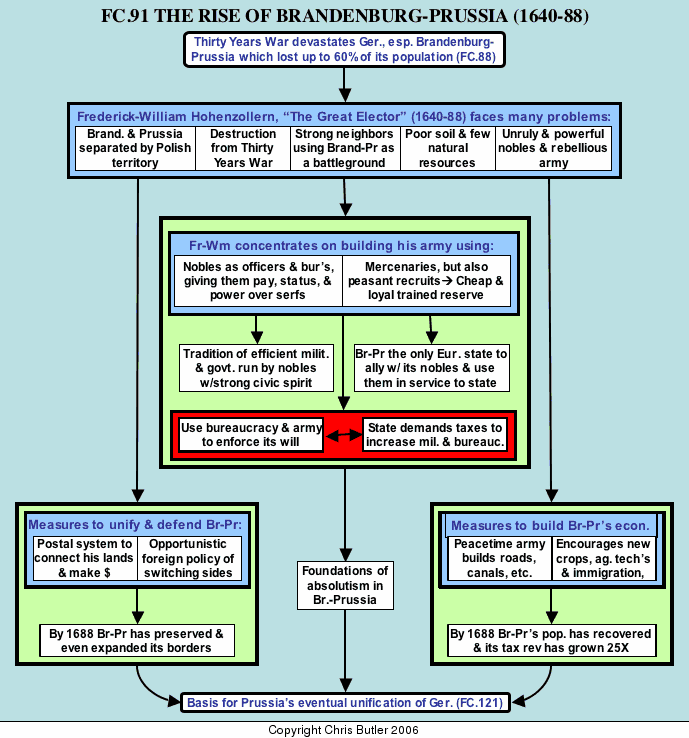

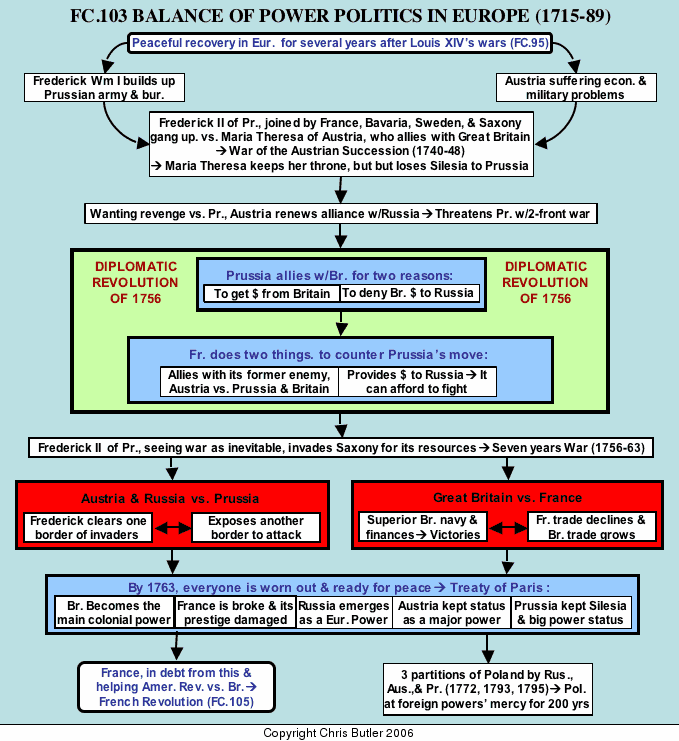

Balance of Power Politics In The Age of Reason (1715-1789)

-

Introduction

-

Diplomatic maneuvering (1715-1740)

-

The rise of Prussia

-

The War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48)

-

The "Diplomatic Revolution" of 1756

-

The Partitions of Poland

-

The American Revolution

-

-

-

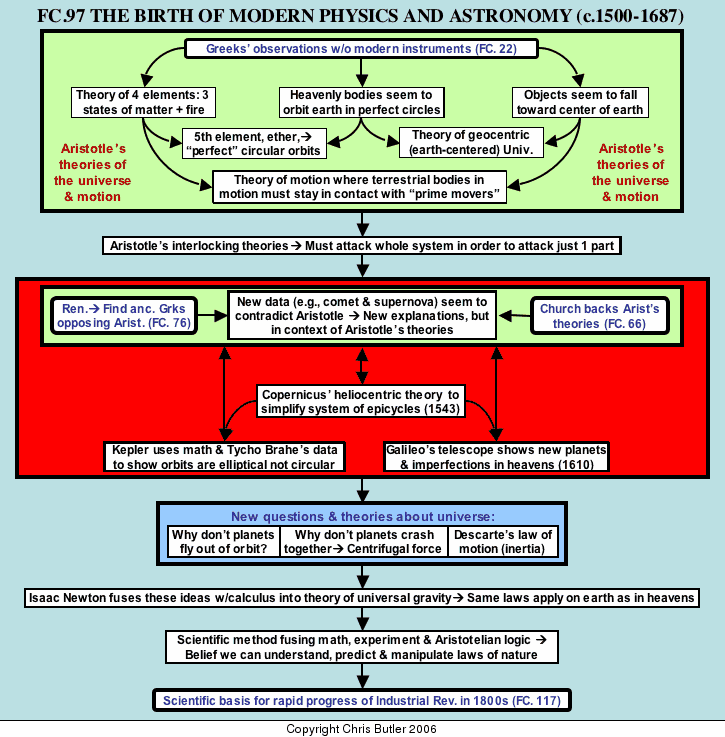

Toward a new universe: the downfall of Aristotle (1543-1687)

-

Pattern of development

-

Johannes Kepler

-

Galileo

-

-

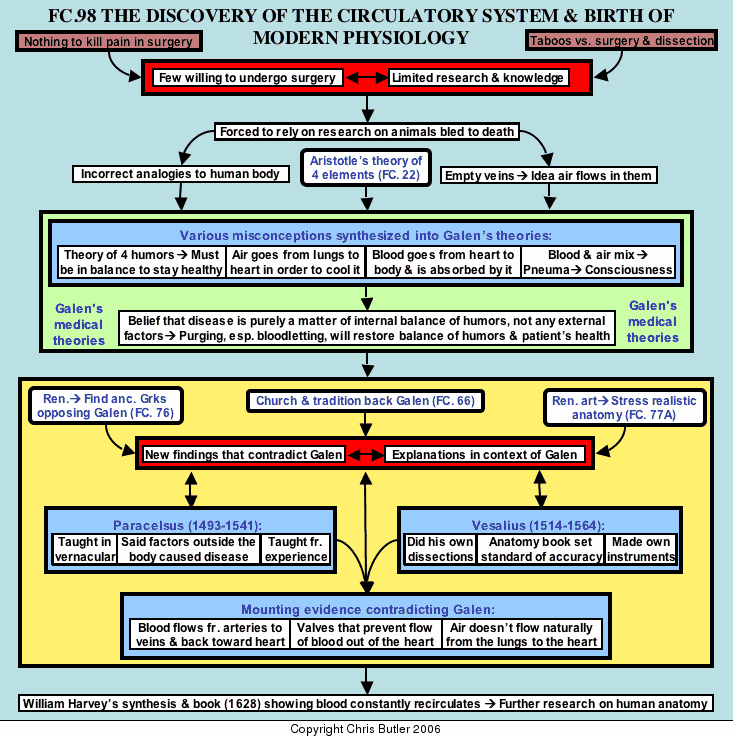

Unravelling The Mysteries of The Heart: William Harvey and The Discovery of The Circulatory System

-

Galen's physiology

-

-

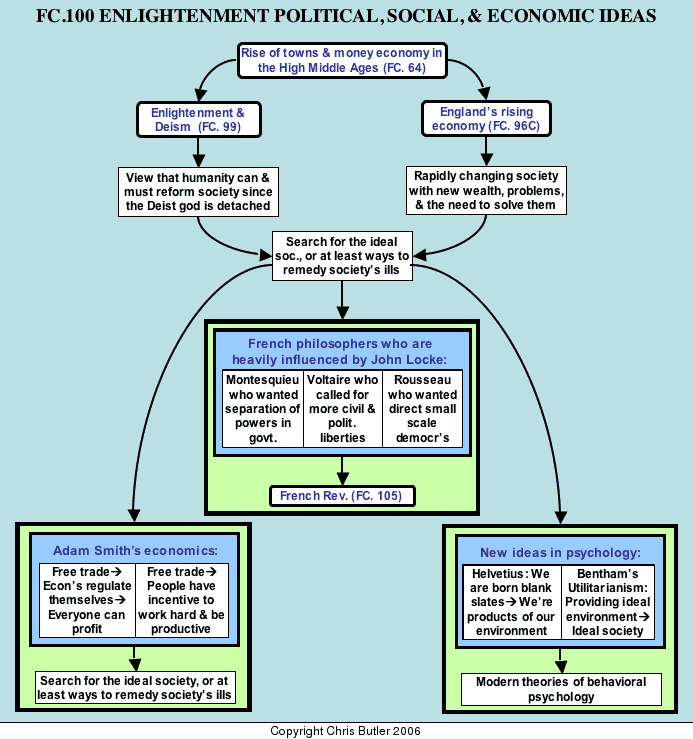

From Faith To Reason: Deism and Enlightenment Philosophy

-

Blinded by Science

-

Deism

-

-

-

The Early Modern era (1500-1789)

-

The Age of Revolutions (1789-1848)

-

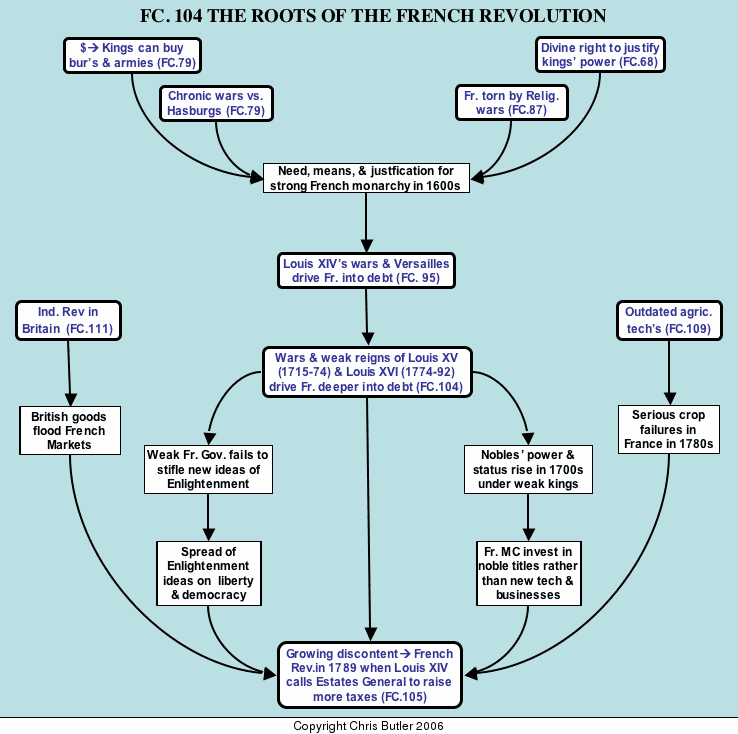

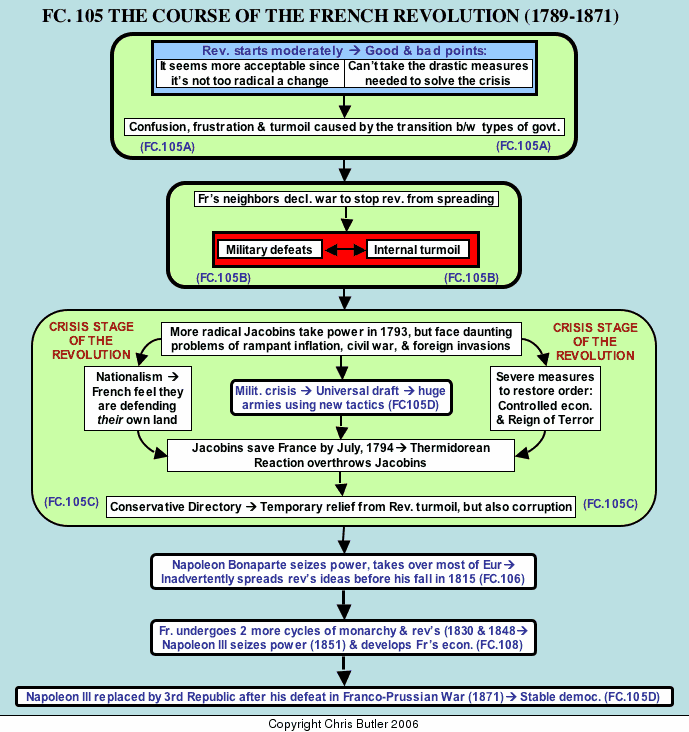

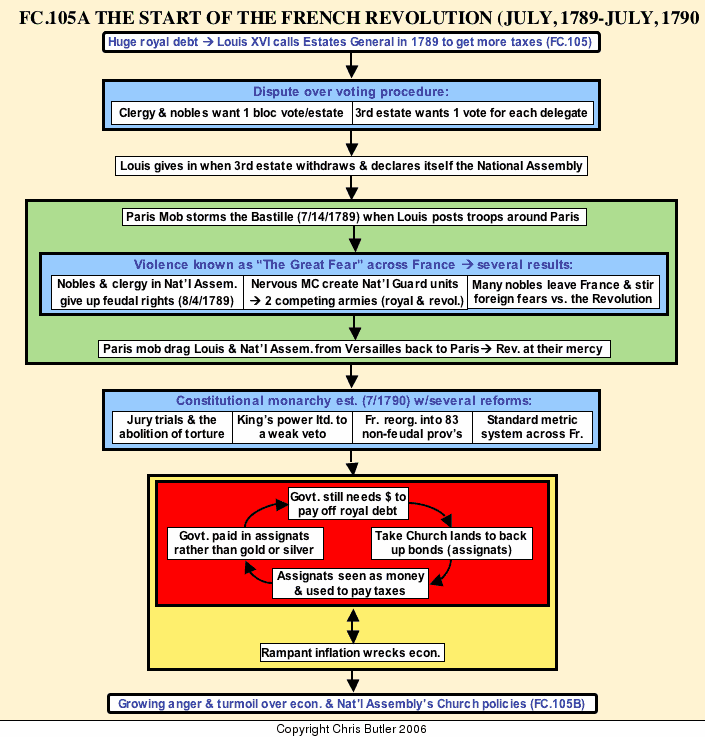

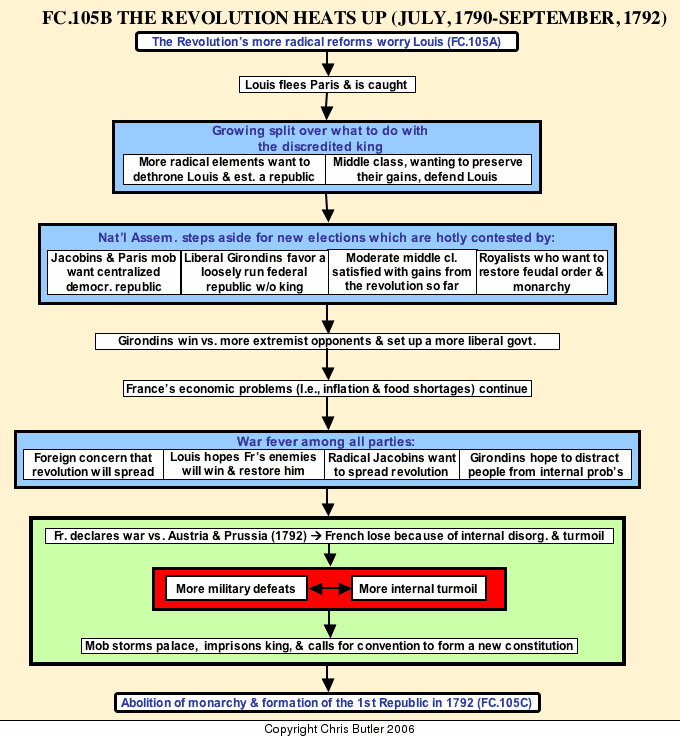

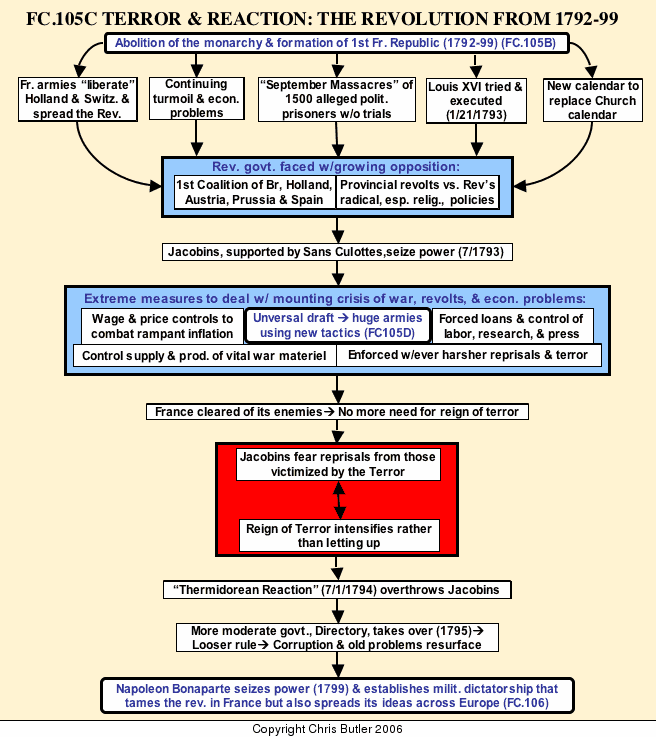

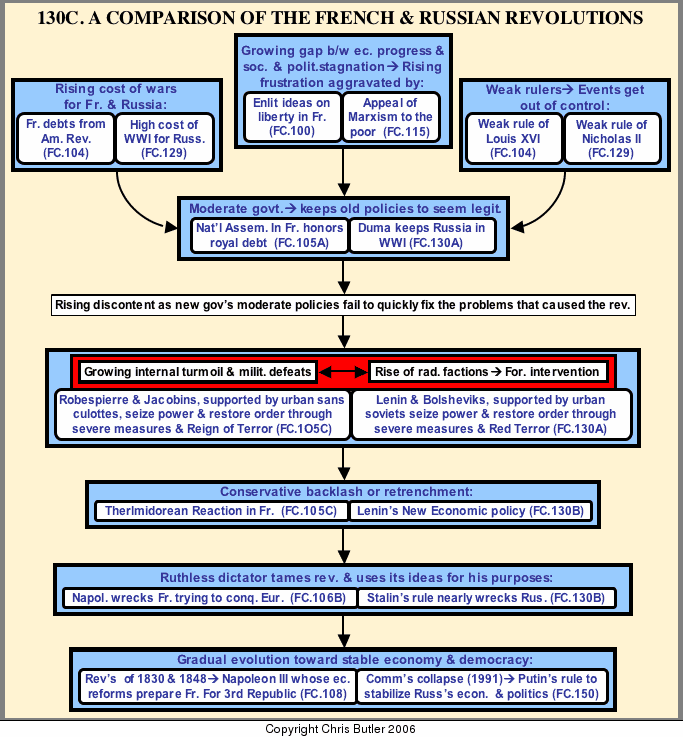

Analyzing The French Revolution and Revolutions In General

-

Introduction

-

The French Revolution

-

-

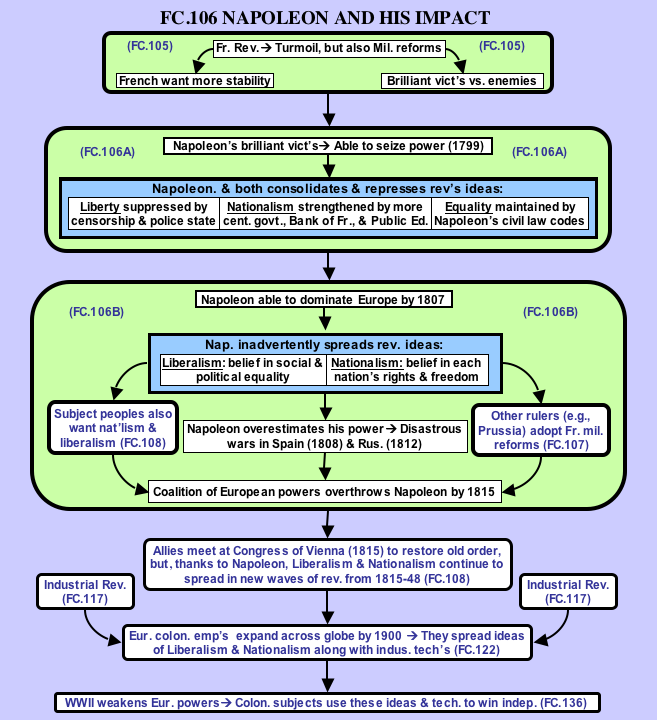

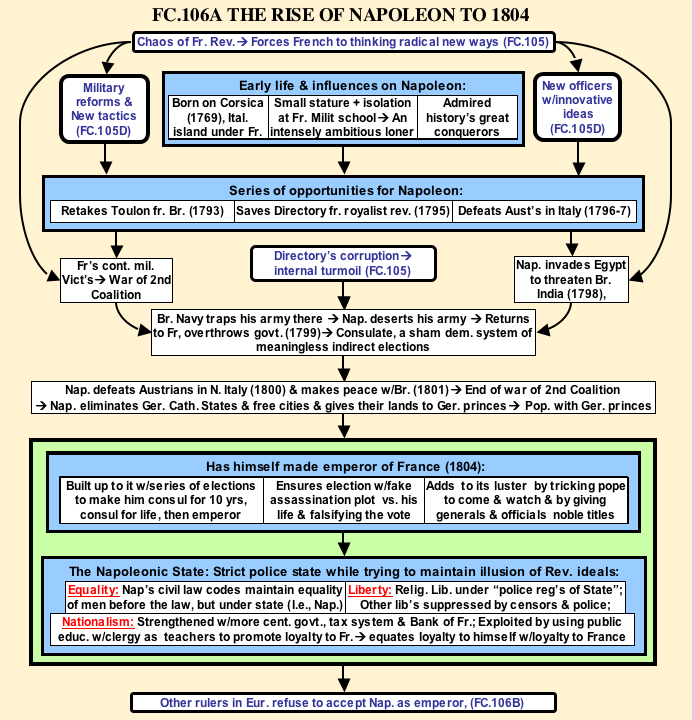

The Rise of Napoleon (1795-1808)

-

Napoleon's rise to power

-

Consolidating his power

-

The Napoleonic state

-

-

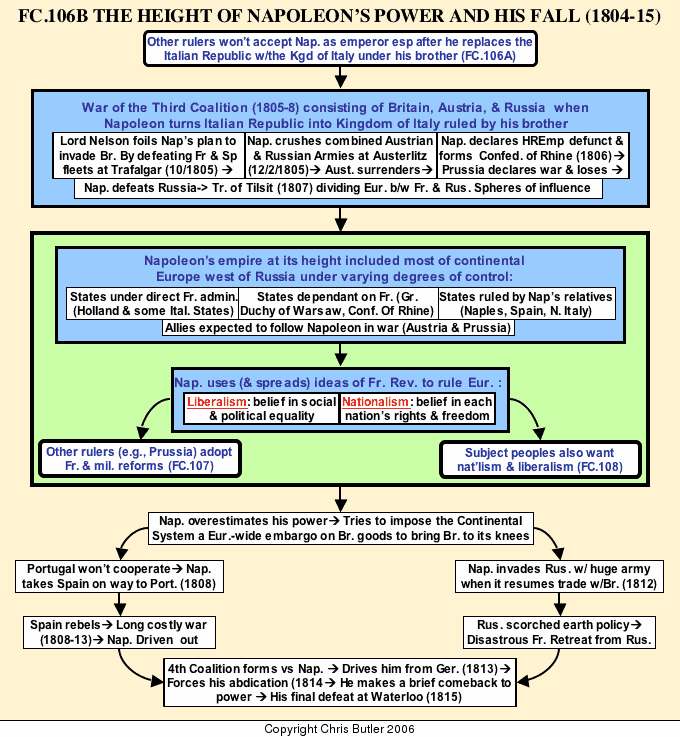

Napoleon's Years of Triumph and Fall (1800-1815)

-

The Continental System and Spanish Ulcer

-

Napoleon's invasion of Russia

-

The end of the Napoleonic Empire

-

-

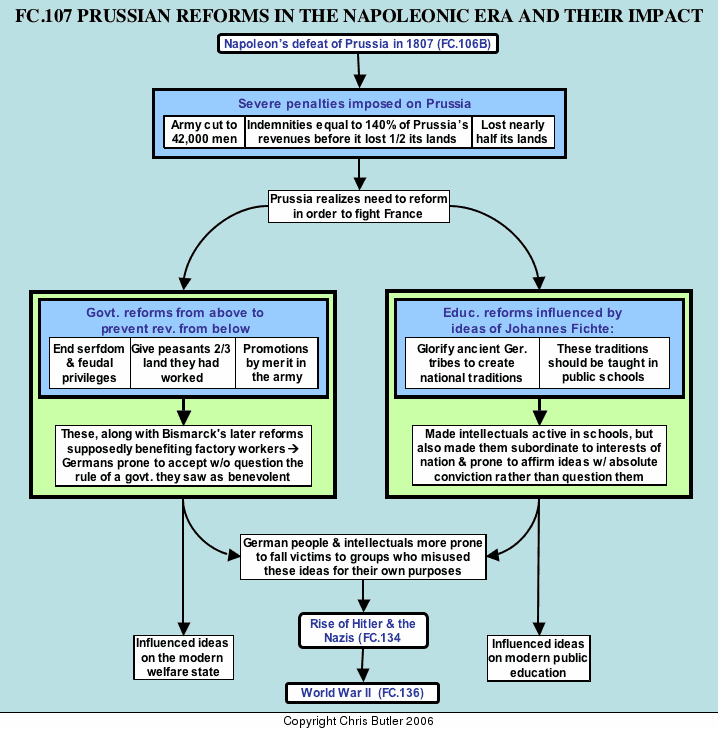

Revolution and Reaction In Europe (1815-1848)

-

The Congress of Vienna

-

The pattern of revolts

-

Revolutions in the 1820's

-

Revolutionary fever spreads: the 1830's

-

The Revolutions of 1848

-

-

-

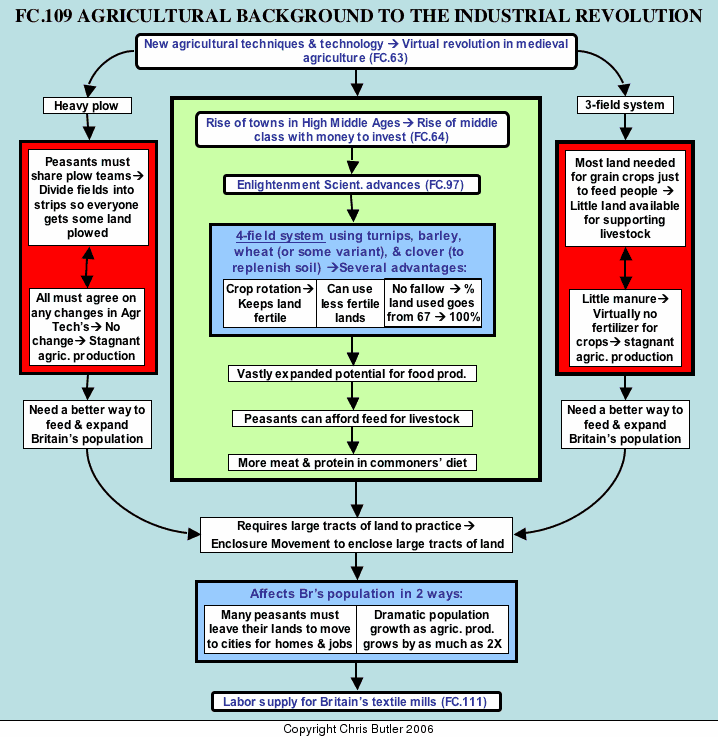

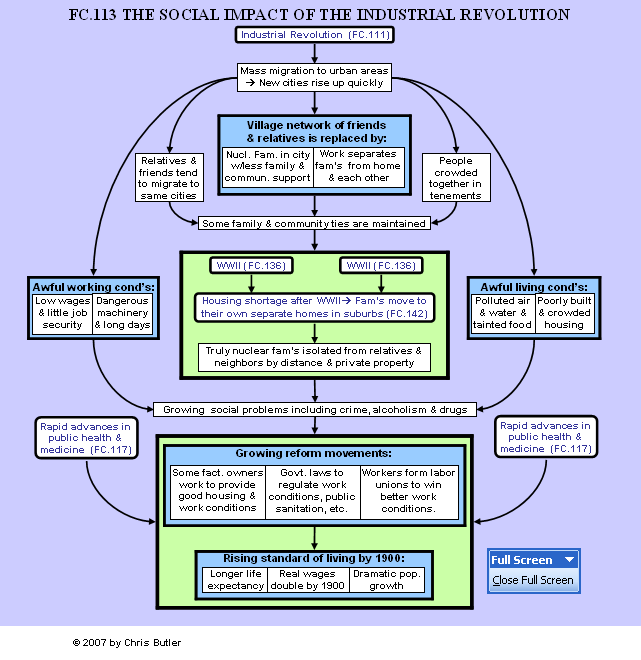

The Agricultural Background To The Industrial Revolution

-

Introduction

-

A new agricultural revolution

-

-

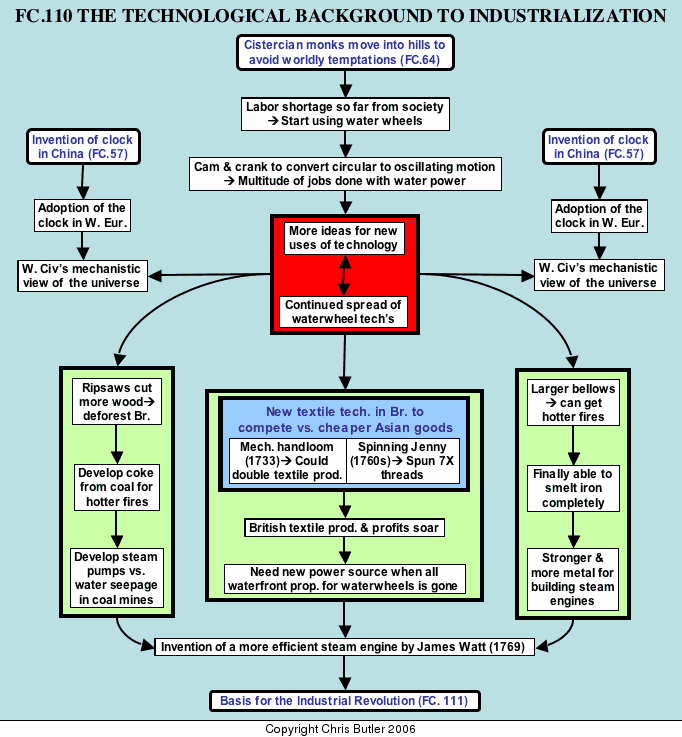

The Technological Background To The Industrial Revolution

-

The medieval roots of the Industrial Revolution

-

The textile industry in Britain

-

Ripsaws and bellows, coal and iron

-

-

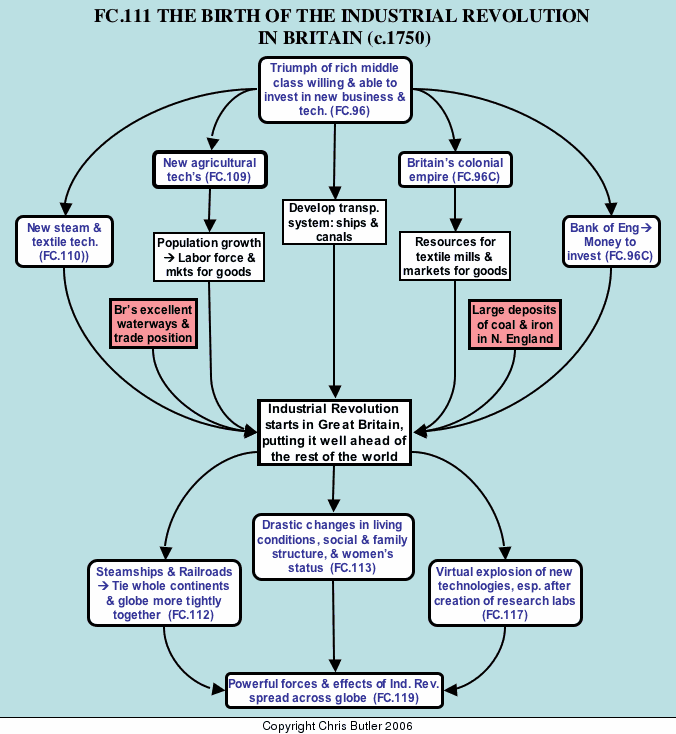

The Start of The Industrial Revolution In Britain (c.1750-1800)

-

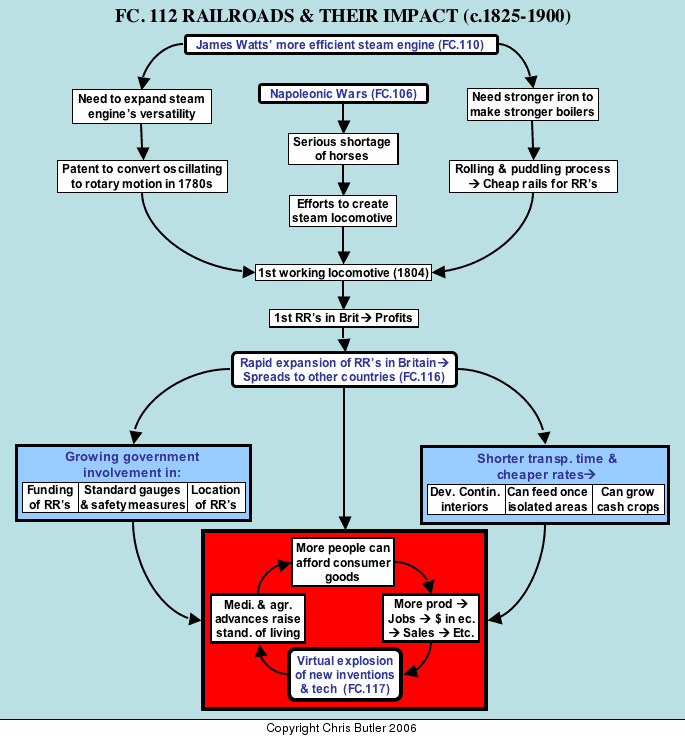

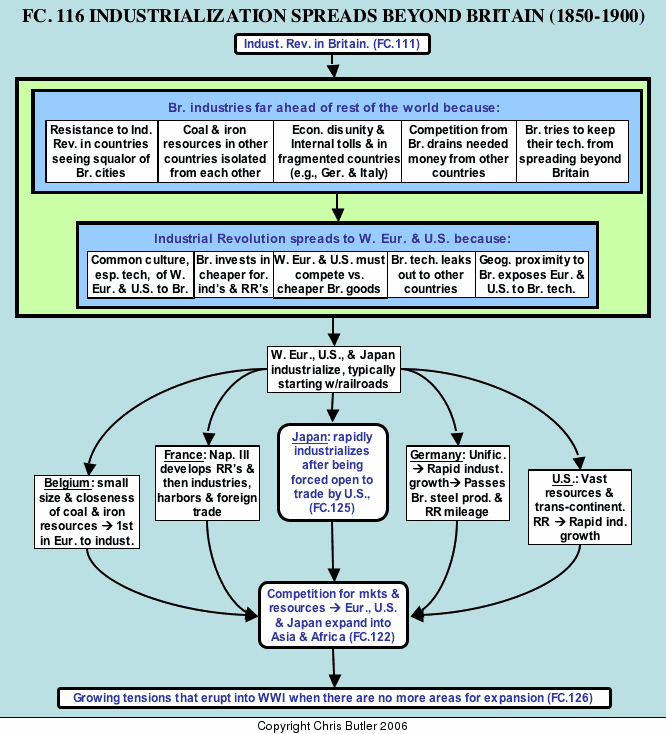

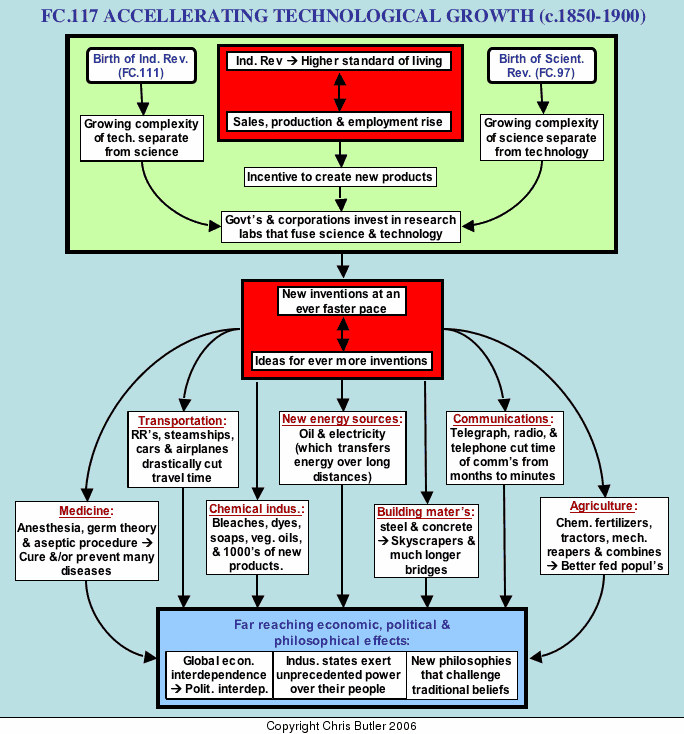

The Spread of Industrialization Beyond Britain (c.1850-1900)

-

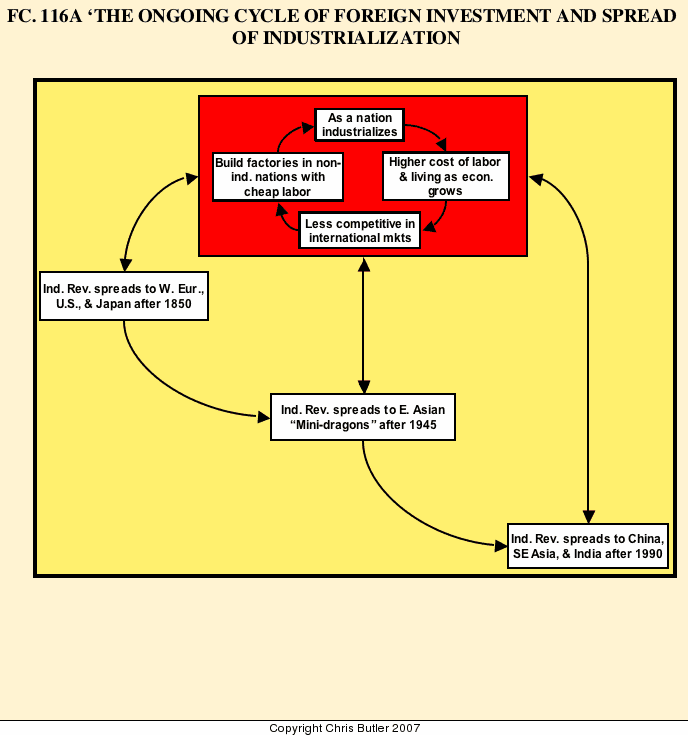

The Cycle of Foreign Investment and The Spread O F Industrialization

-

-

Nationalism & imperialism in the Late Nineteenth Century

-

Disease and The Decline of The Hapsburg Empire In The Late 1800's

-

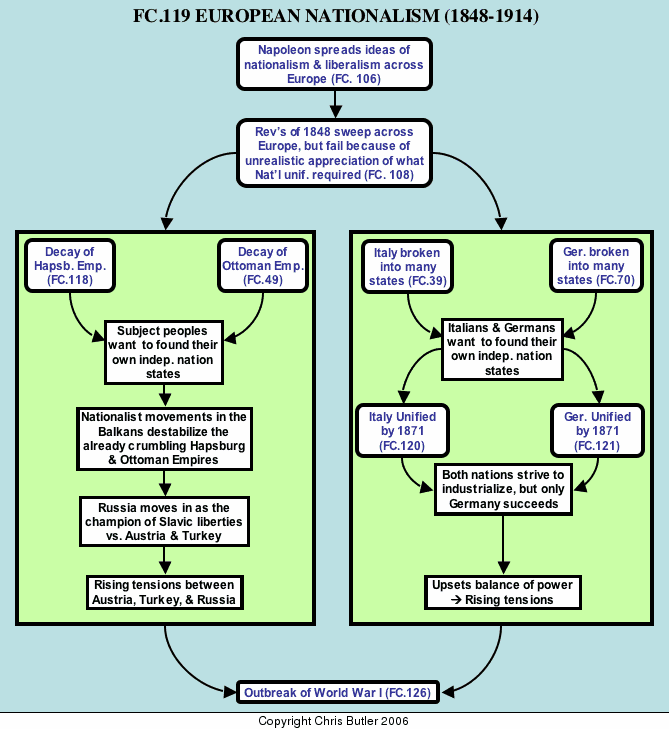

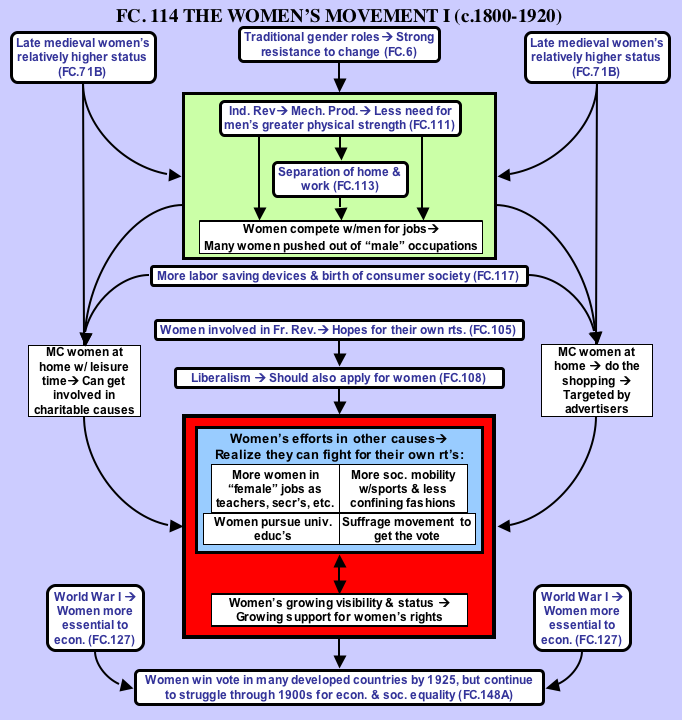

Nationalism and Its Impact In Europe (1848-1914)

-

Introduction

-

-

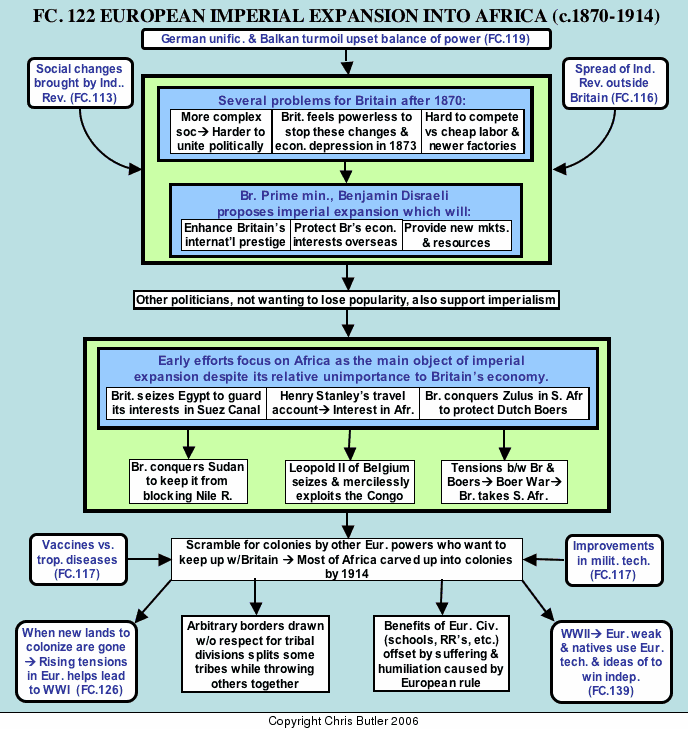

European Imperial Expansion In Africa (c.1870-1914)

-

Introduction

-

The "Dark Continent"

-

-

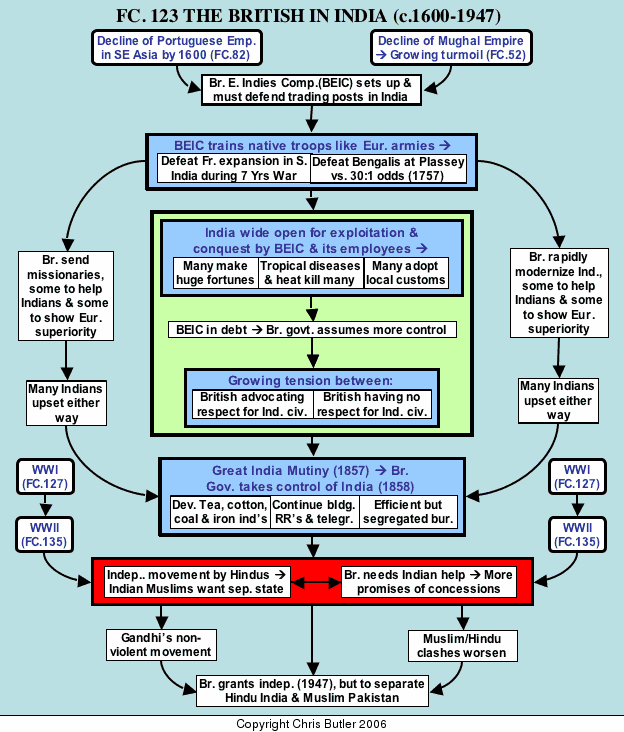

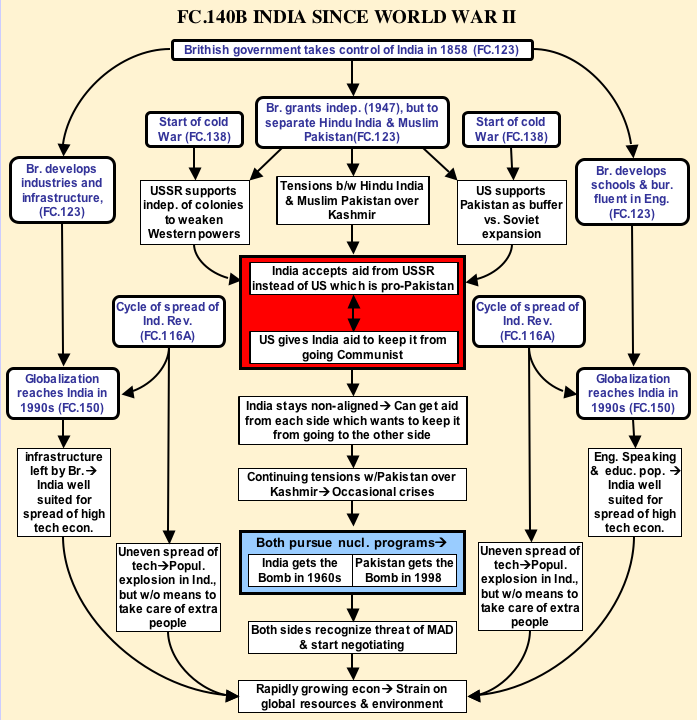

British Rule In India (c.1600-1947)

-

Introduction

-

Company expansion (1601-1773)

-

Growing parliamentary control and rising tensions (1778-1857)

-

From the British Raj to independence (1858-1947)

-

-

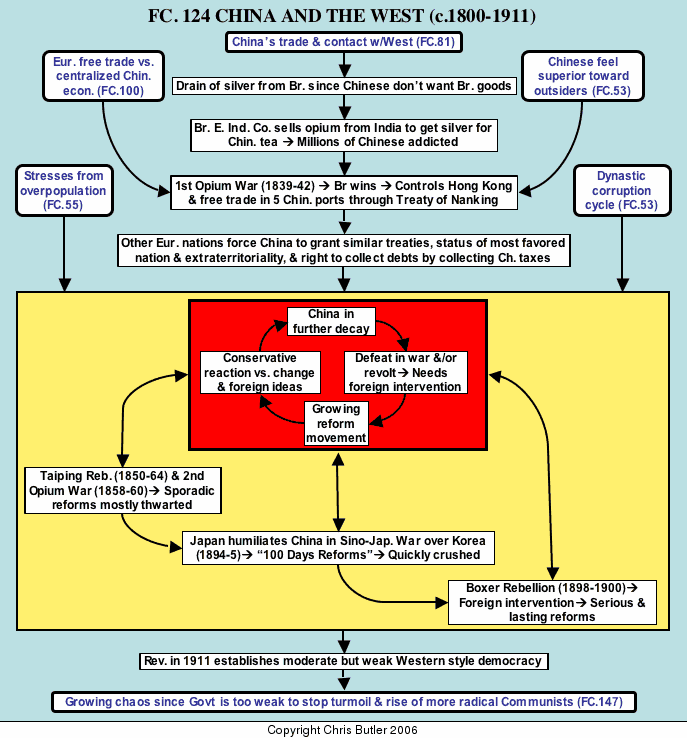

The Decline of Imperial China (c.1800-1911)

-

Introduction

-

The Opium War and its aftermath (1839-64)

-

-

The Emergence of Modern Japan (1868-1937)

-

Decline of the Tokugawa Shogunate

-

The Meiji Restoration (1868-c.1890)

-

Japan's quest for empire

-

-

-

-

The upheavals of the early twentieth century (1914-45)

-

War and revolution in Europe (1914-20)

-

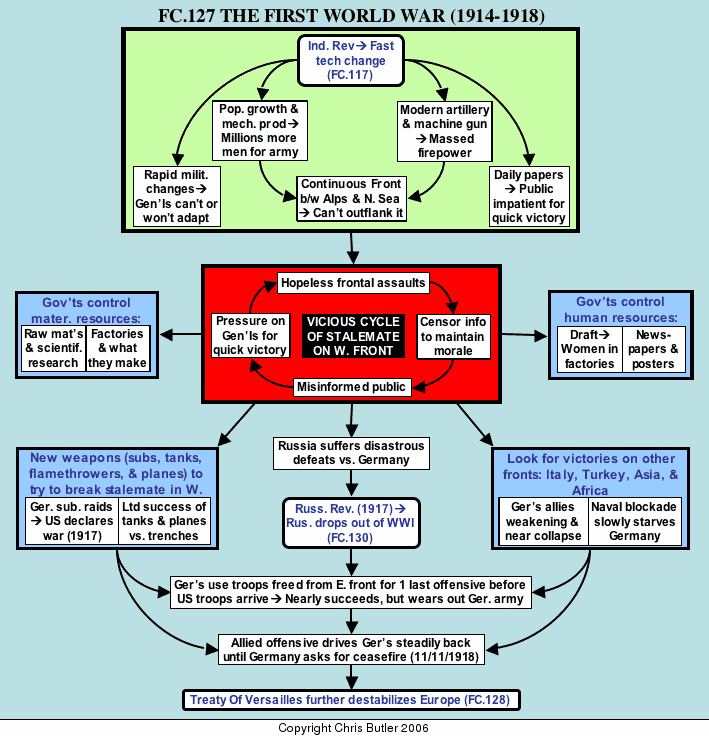

The Causes and Outbreak of World War I

-

Introduction

-

Economic competition

-

German unification

-

The Road to war (June-August, 1914)

-

-

-

The war of movement (August-September, 1914)

-

The new face of war

-

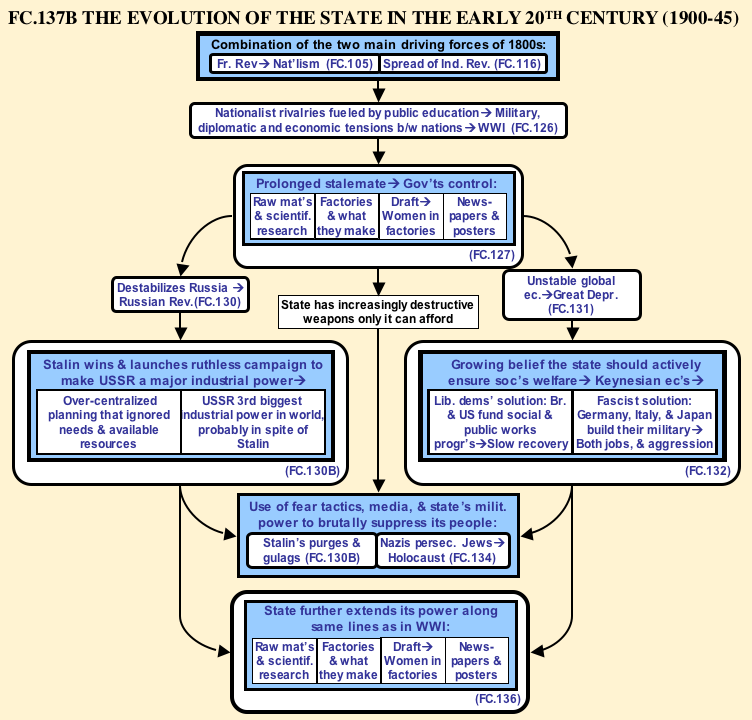

Total War

-

New fronts and new weapons

-

Material and human resources on the home front

-

The Eastern Front

-

New Fronts

-

New Weapons

-

The end of the "war to end all wars" (1917-18)

-

-

-

Introduction

-

Europe's colonies

-

Eastern Europe

-

-

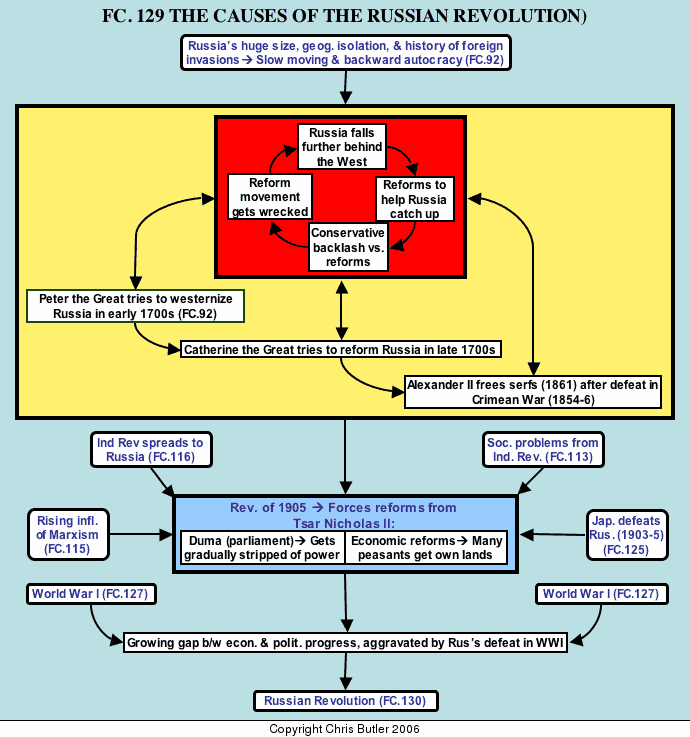

Background To The Russian Revolution

-

Causes and background

-

-

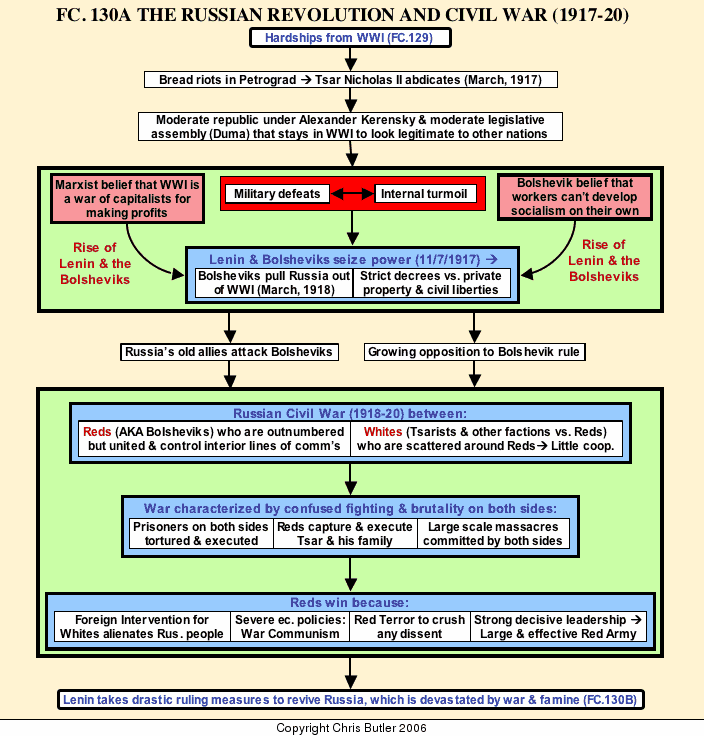

The Russian Revolution and Civil War (1917-20)

-

The 1917 Revolution and Bolshevik triumph.

-

The Russian Civil War (1918-20).

-

-

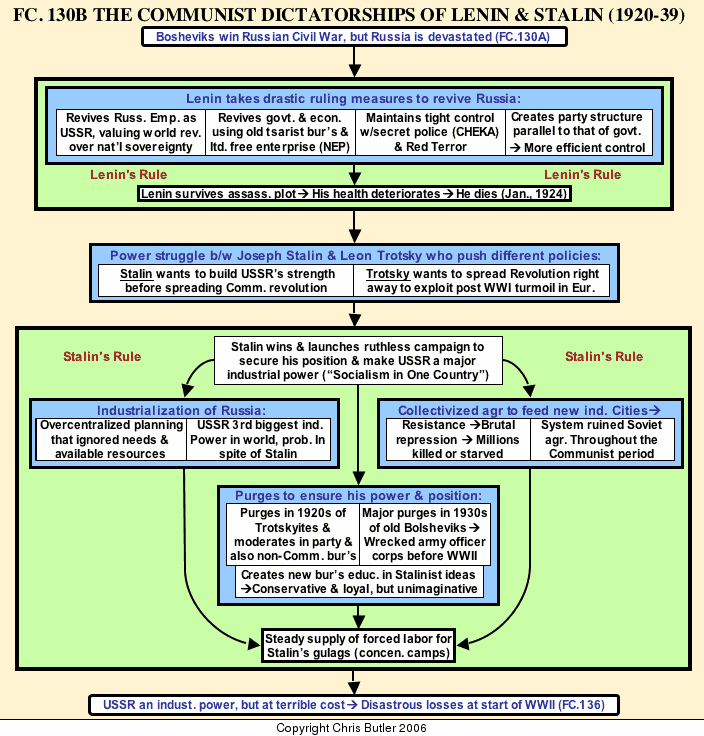

The Communist Dictatorships of Lenin & Stalin (1920-39)

-

Lenin’s Rule

-

Stalin’s revolution (1924-40).

-

-

-

Depression, Fascism, and world war (1920-45)

-

Post War Boom and Bust (1920-29)

-

The illusion of prosperity

-

The Crash

-

-

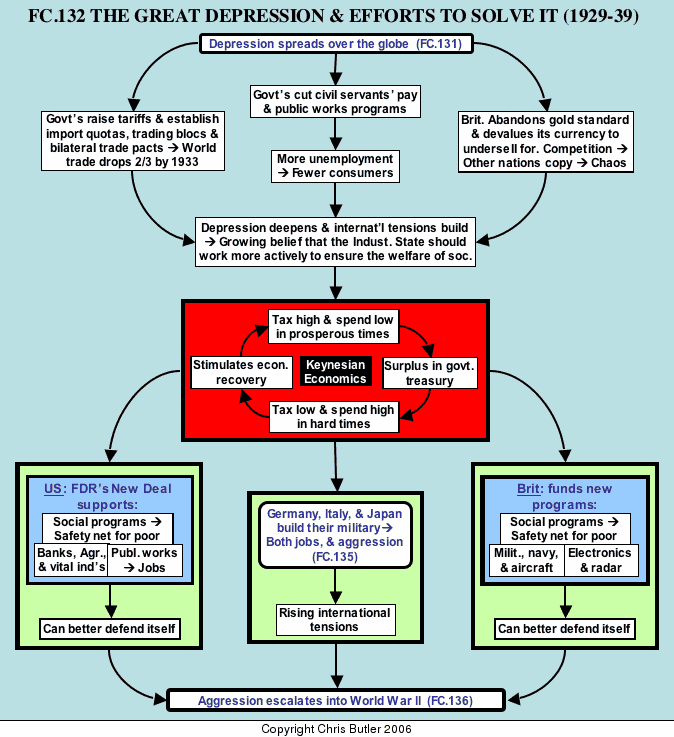

The Great Depression (1929-39)

-

Efforts to solve the Depression

-

Keynesian economics: a new view of the state's role in the national economy

-

-

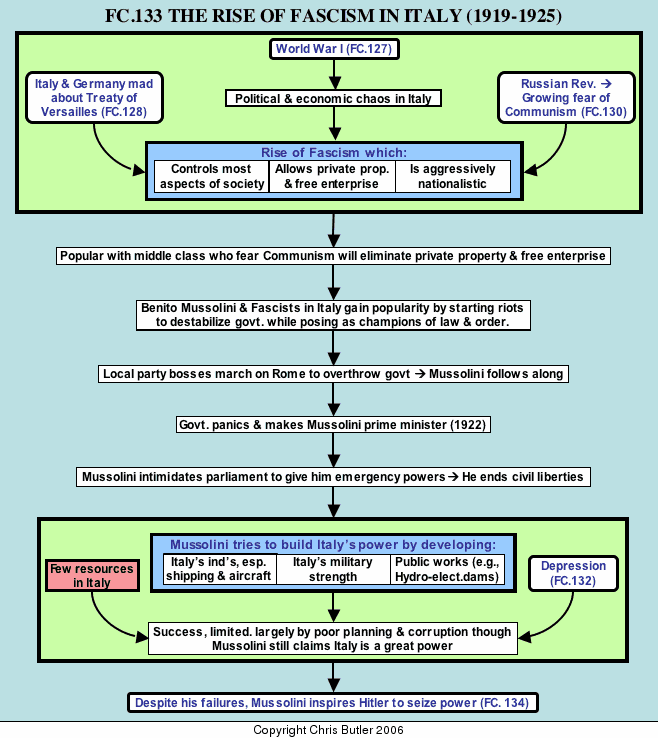

Benito Mussolini and The Rise of Fascism In Italy (1919-25)

-

Introduction: the response to Communism

-

Mussolini and the rise of Fascism in Italy

-

-

Adolf Hitler and The Rise of Nazism In Germany (1919-39)

-

Introduction

-

From chancellor to dictator (1933-38)

-

The growing darkness

-

Conclusion

-

-

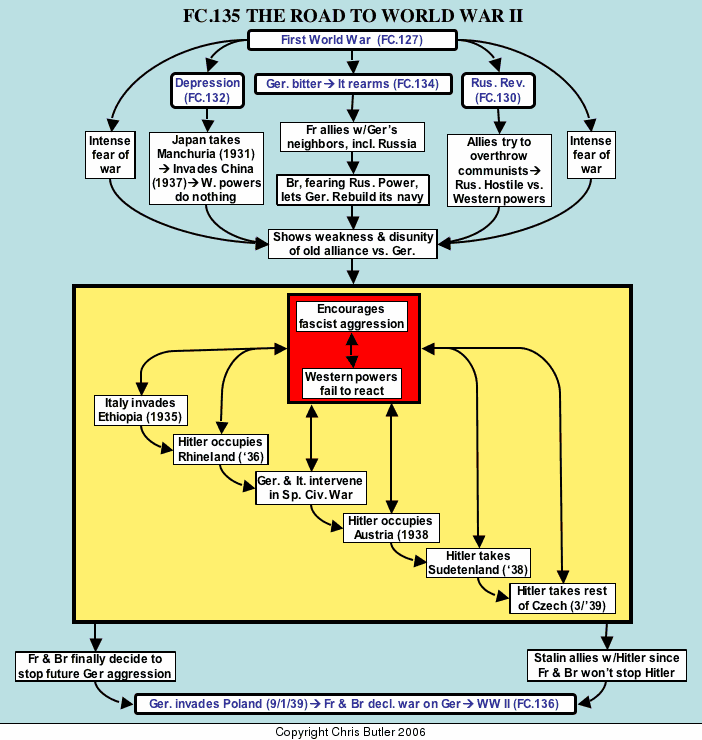

The Road To World War II (1919-39)

-

Introduction

-

France, Britain and the Treaty of Versailles

-

The Depression and the Far East (1931-41)

-

The Russian Revolution and Soviet Union

-

The cycle of aggression and the road to war in the 1930's

-

-

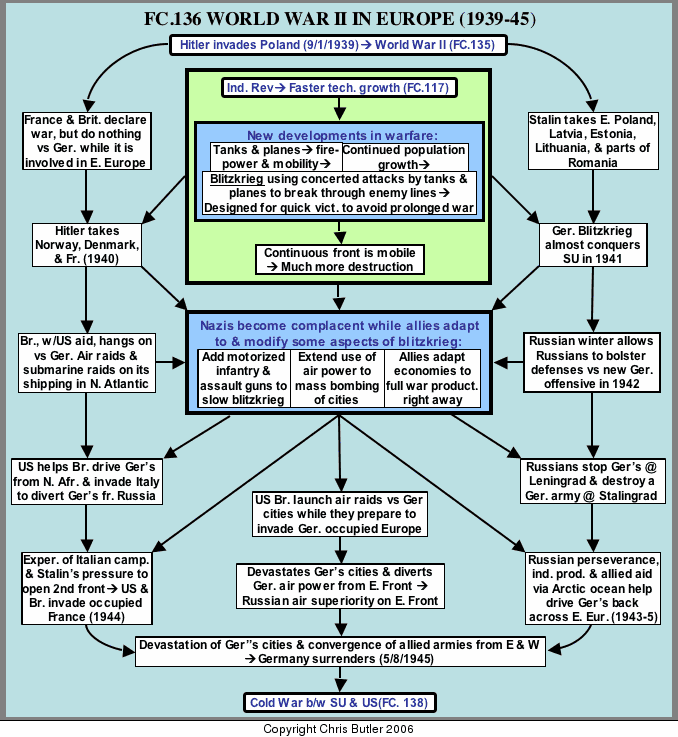

World War II In Europe (1939-45)

-

Blitzkrieg (1939-41)

-

The allied response and counter-attack (1942-45)

-

Germany triumphant (1939-41)

-

The Eastern Front (1939-1944)

-

The Western Front (1942-44)

-

The end of the Third Reich (1944-45)

-

-

-

-

-

-

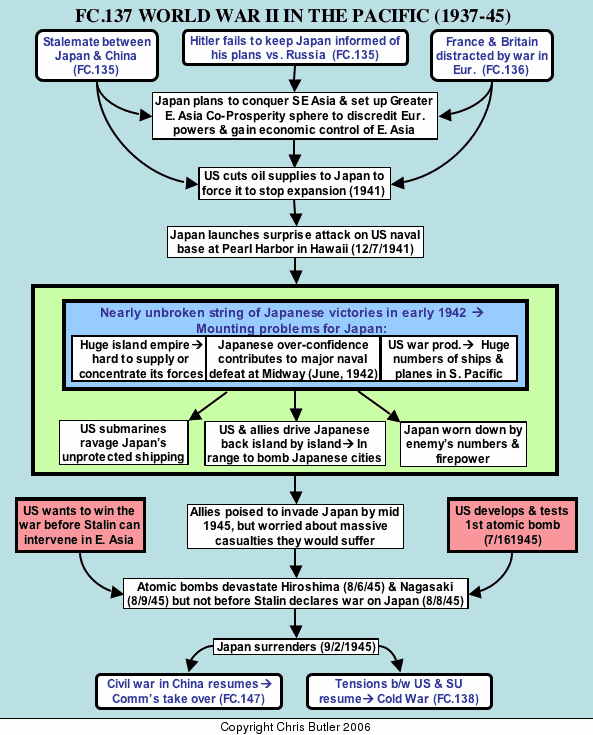

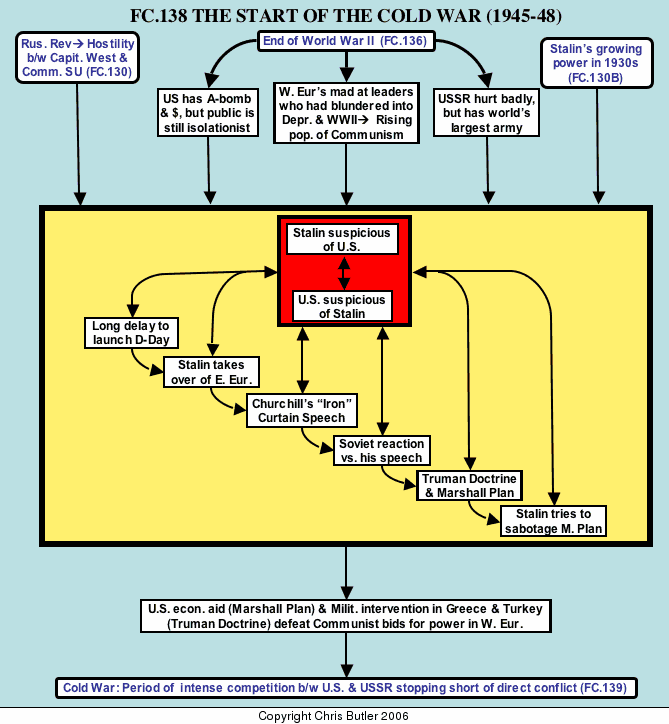

A New Balance of Power and Cold War (1945-1948)

-

The aftermath of World War II

-

A new balance of power emerges (1945-48)

-

The Cold War begins (1948-55)

-

-

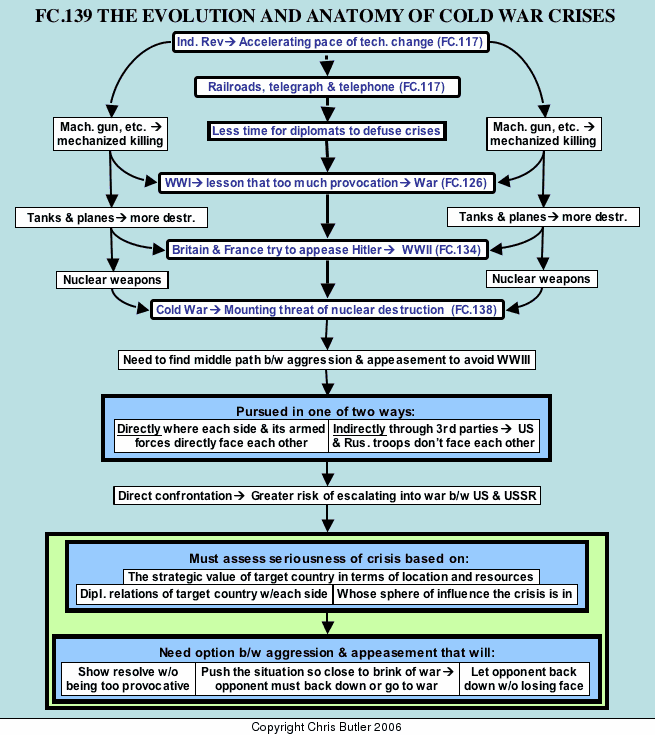

New Rules For A New Game: The Evolution and Anatomy of Cold War Crises

-

Introduction

-

Wars and crises up to 1945

-

The new rules of the game

-

-

-

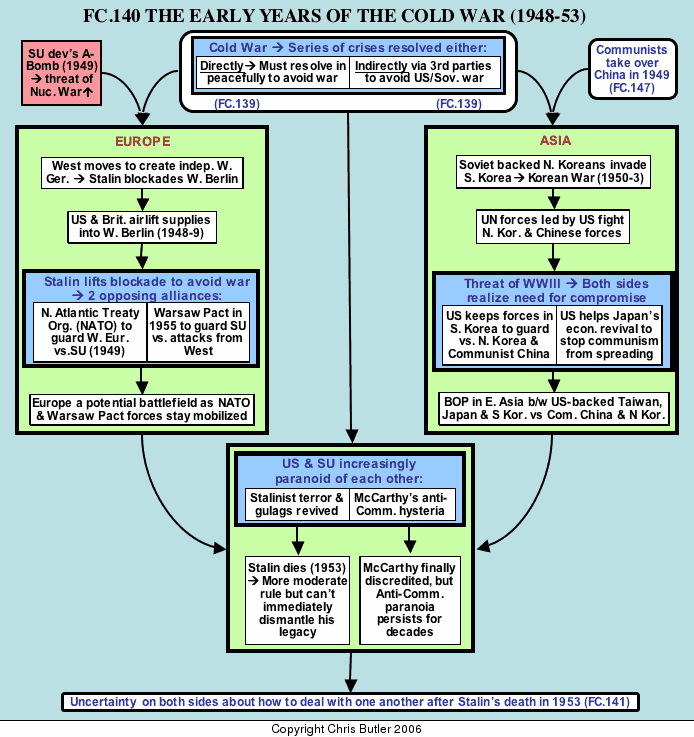

The Cold War in Europe (1948-55)

-

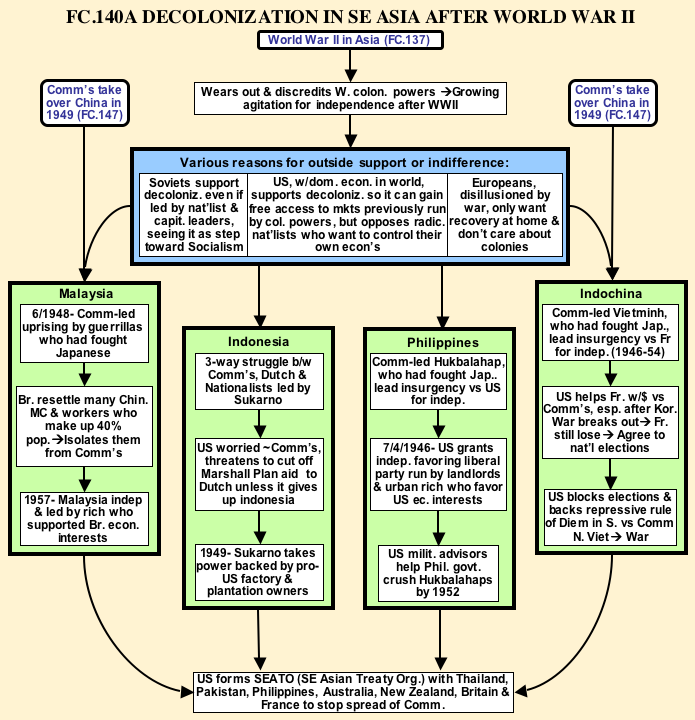

The struggle widens: East Asia (1945-53)

-

-

Missed Opportunities: The Aftermath of Stalin's Death (1953-56)

-

Introduction

-

Mixed signals

-

Nikita Khrushchev

-

Unrest and crisis in Eastern Europe

-

-

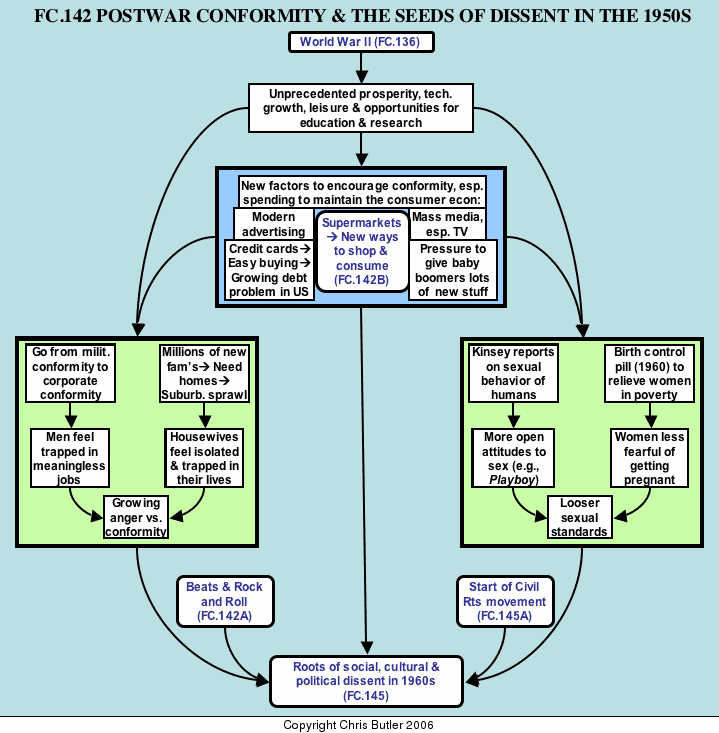

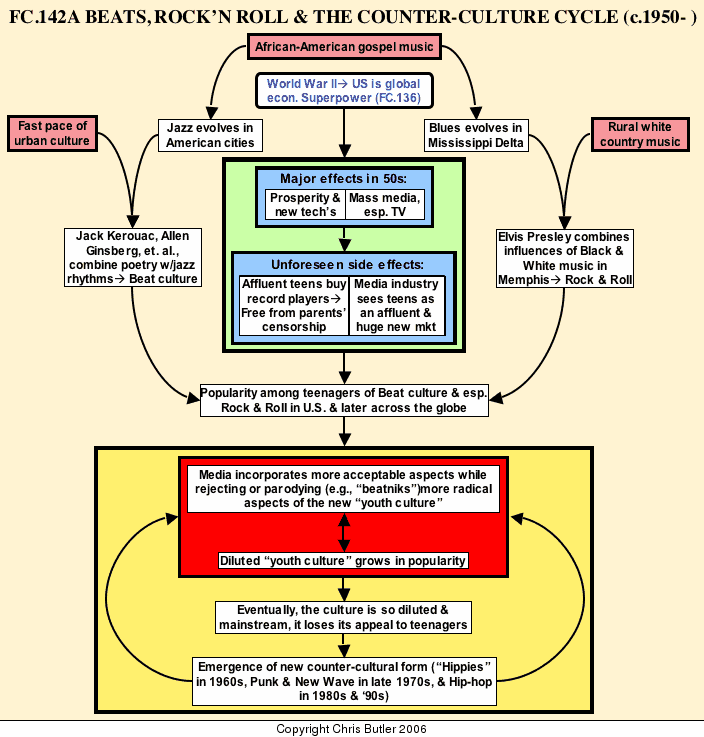

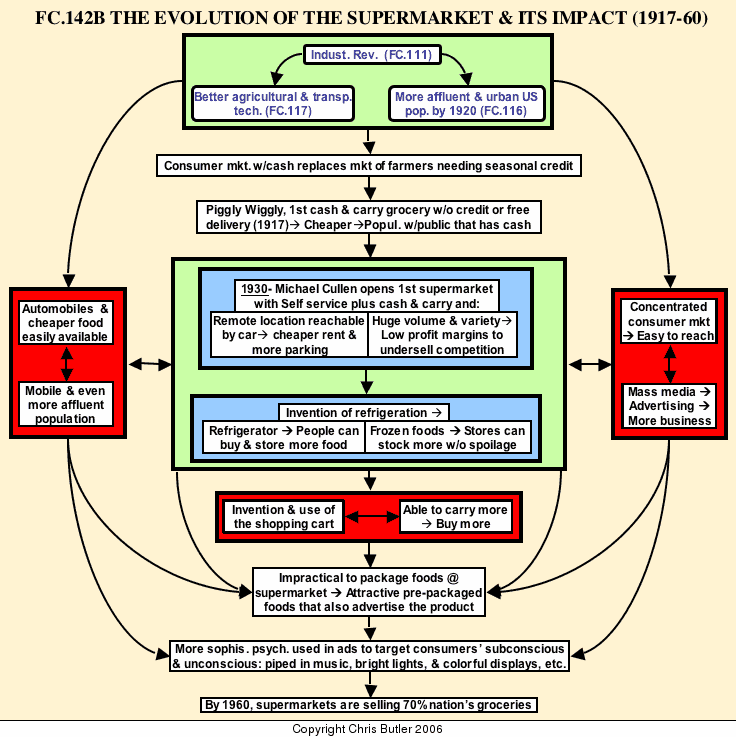

Postwar Conformity and The Seeds of Dissent In The 1950s

-

Pressures to conform

-

Conformity and deformity

-

Things we don’t talk about

-

Conclusion: toward a decade of dissent

-

-

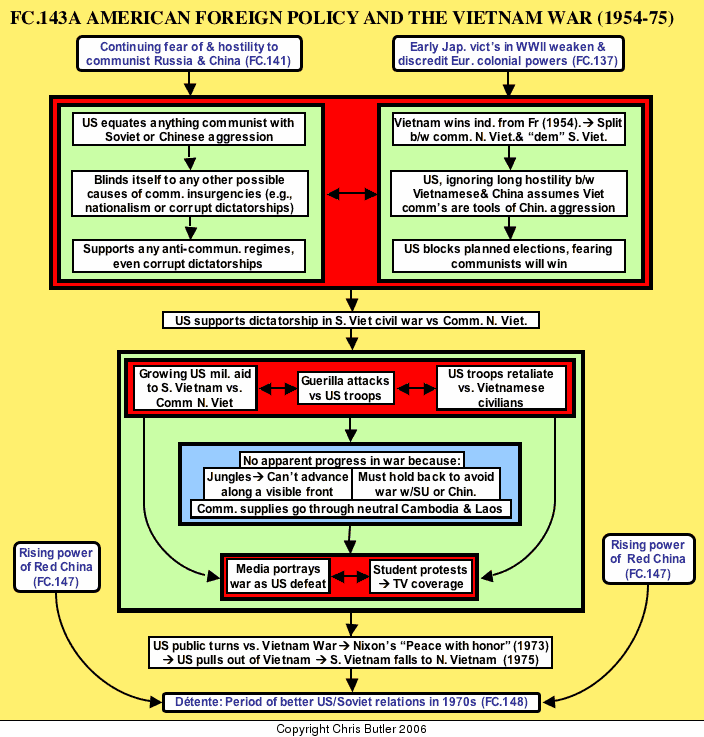

The Height of The Cold War (1957-72)

-

Rising tensions

-

The Berlin Wall

-

The Cuban Missile Crisis

-

Vietnam (1954-75)

-

-

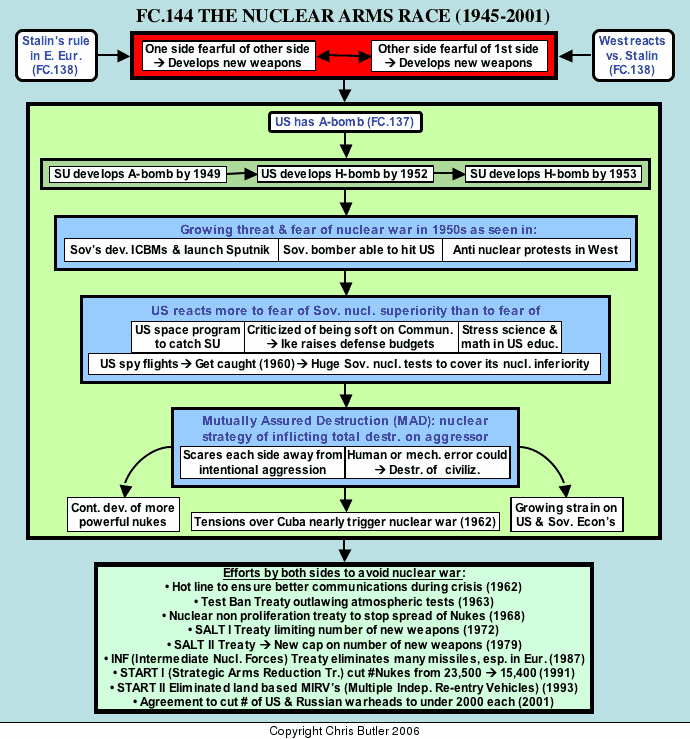

The Nuclear Arms Race (1945-2001)

-

Introduction

-

MAD

-

Gradually defusing the nuclear time-bomb (1962-2001)

-

-

-

The later Cold War and the “New World Order” (1970-2000)

-

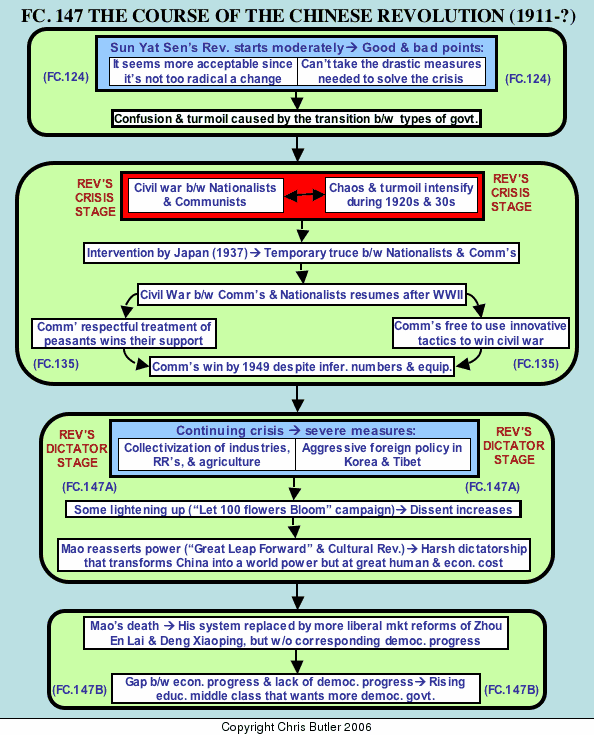

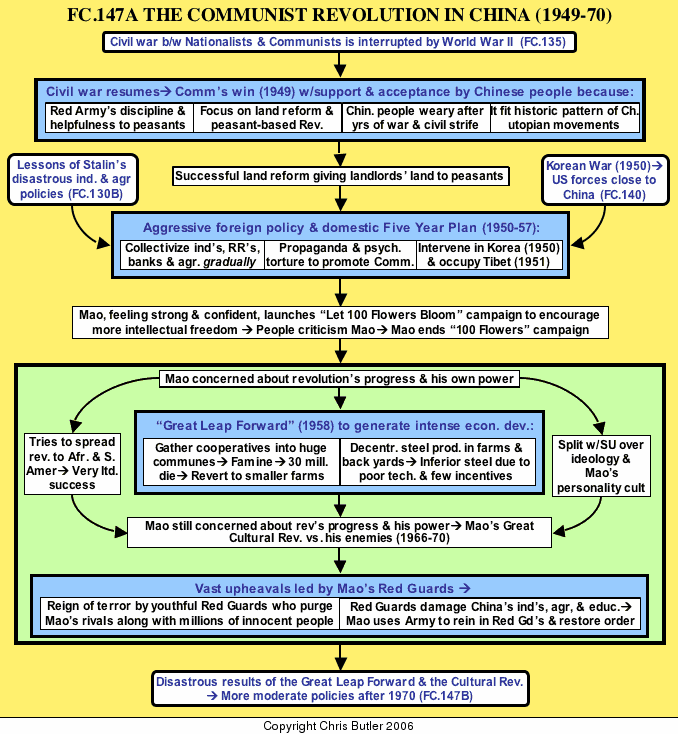

A More Detailed Look At The Chinese Revolution

-

The Cultural Revolution (1966-70)

-

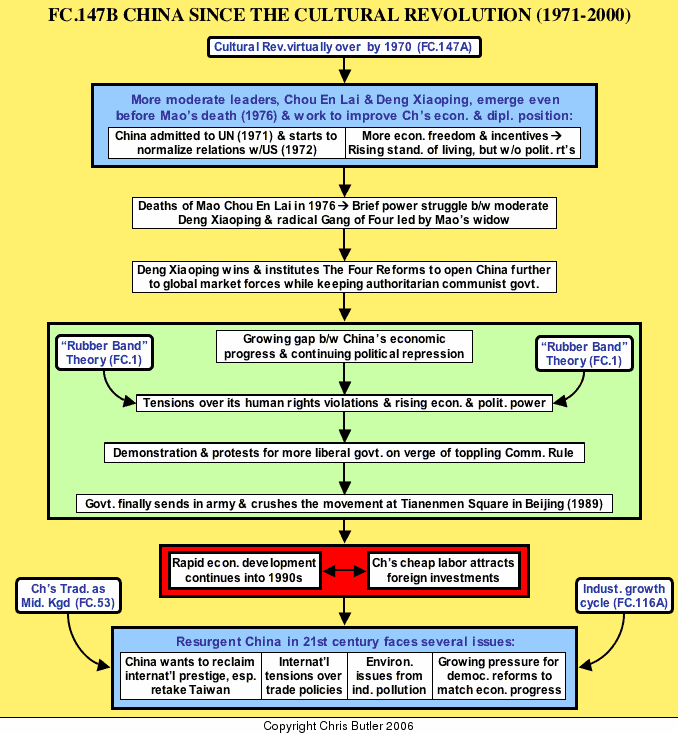

China since the Cultural Revolution

-

-

PrehistoryPrehistory, the rise of civilization, and the ancient Middle East to c.500 B.C.E

Prehistory to c.3000 BCEUnit 1: Prehistory and the rise of Civilization to c.3000 B.C.E.

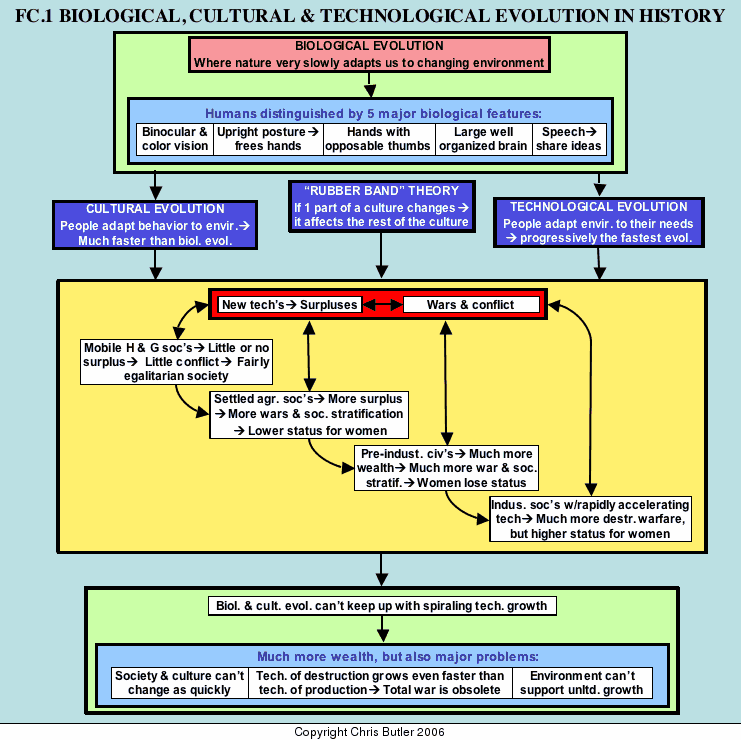

FC1Biological, Cultural, and Technological Evolution in History

Introduction

There are three types of evolution that have driven the development of human societies. The first of these is biological evolution where nature very slowly adapts us physically to our changing environment. Whether one believes in the theory of dynamic biological change and evolution or a more static creationist model of biology, one cannot deny we are biological beings with certain characteristics that largely distinguish us from other animals. There are five major characteristics that make humans unique. One is our binocular and color vision that gives us depth perception and a more detailed view of our surroundings respectively. This sends a lot of information to our brains for processing, making us very much a visually oriented species with 90% of the information we take in coming in through the eyes. Second we have upright posture, which frees our hands. This brings us to the third factor, our hands with opposable thumbs, which allow us to manipulate various objects and our environment. That in itself would be worth very little if it were not for the fourth characteristic, our brain that allows us to use our hands in intelligent and creative ways. The brain also makes possible the fifth characteristic, speech which allows us to share knowledge and ideas quickly so each generation does not have to rediscover that knowledge on its own, giving it time to discover and develop new knowledge and ideas.

This unique combination of biological characteristics is the basis for two other types of evolution: cultural and technological. One can see cultural evolution as how people adapt their behavior to the environment. Since these are conscious rather than totally random, or non-existent, changes, they occur at a much faster pace than biological change. However, the force of tradition typically keeps people from rapidly changing long-standing cultural traditions that generally have served society well in the past. This is because people through most of history have barely survived with little or no surplus, giving them little or no margin for error if the new change does not work, and making them reluctant to change cultural norms very rapidly.

Technological evolution enables people to adapt or change their environment to meet their needs. This is often something that can be done without immediately changing cultural norms. Therefore, it tends to happen at a much faster rate than cultural change. Not only that, but each new invention, being developed consciously and often based on previous successful inventions, is likely to improve the standard of living. This makes people more likely to develop new inventions, further improving their standard of living, and so on.

The “Rubber Band Theory”

One of the most important concepts to understand about history is how any particular event or development rarely has just one cause or just one result. Typically, if one part of a culture changes, it leads to changes in the other parts of the culture. One can visualize each part of a culture (social structure, political structure, technology, the arts, religion, economy, military institutions, etc.) as being connected to each of the other parts by rubber bands. If one part (e.g., the economy) changes and moves forward, it tries to pull all the other parts along with it. If any, some, or all the other parts do not move, the rubber bands connecting them stretch as the distance between them increases. If the distance and tension become too great, one or more of the rubber bands snaps, signifying some form of breakdown or dramatic change, such as a revolution.

An overview of the flow of history

The combination of cultural and technological change along with the Rubber Band Theory helps explain the overall flow of history. The process driving this comes increasingly from technological change. This leads to surpluses that lead, among other things, to wars and conflict since people have typically fought over material wealth. These surpluses and the wars they cause lead to efforts to find new and better technologies. These create even more surpluses and wars, more new technologies, and so on. Since there are more technologies on which to base new ones each time this feedback cycles around, technology growth continually accelerates in speed and intensity. This process has created four successive stages of development in human society, each of which feeds back into the cycle of technological growth, thus leading to the next stage.

First, through the vast majority of our species’ existence our ancestors followed a hunting and gathering way of life, with men typically doing the hunting and women gathering fruits and grains while watching the children. Such societies were highly mobile as they pursued wild game. They had little or no surplus and therefore virtually no private property since, being mobile, they could carry very little with them. By the same token, they had to be highly cooperative and share freely, since a man or the men as a group did not always bring home any meat and had to rely on what the women had gathered. All this made for a somewhat egalitarian society with little difference in status between men and women. At this early stage, with little previous technology to draw upon, new technologies developed slowly.

That changed somewhat with the next stage: the invention of agriculture (c.8000 B.C.E.). This forced people to settle down as they generated progressively larger surpluses. For the first time, people could amass private property, which led to different social classes distinguished by wealth. That in turn triggered conflict within the society and wars between societies. With survival based increasingly on brute strength, men emerged as the leaders and women’s status started to drop.

Social stratification and conflict accelerated during the next stage, pre-industrial civilization, which started c.3000 B.C.E. Two new inventions especially distinguished this stage. First of all, metallurgy, provided new forms of wealth and weapons with which to fight over that wealth. Writing helped people keep track of and amass larger amounts of wealth. More wealth led to wars of much greater intensity, frequency, and destructiveness. It also further reduced the status of women who had lost virtually all control over property by now.

The fourth stage, industrial society, started in Britain (c.1750) and has spread rapidly across the globe since then. This period has been especially marked by the rapid acceleration of technological growth. Unfortunately, this has been particularly true of military technology, which has increased the destructive power of warfare by several quantum leaps as seen in the two world wars which dominated the first half of the twentieth century. Ironically, the status of women has risen dramatically in industrial societies, largely because machines have reduced the need for or value of brute muscle, thus making women more competitive for jobs and opportunities, even in the military.

The challenges of modern society: the rubber bands stretched

Technology is a double edged sword that has helped generate by far the highest standard of living and longest life expectancy in human existence. But the spiraling rate of technological growth over the past 200 years has created progressively greater stresses on the “rubber bands” holding human society together. This is because, compared to technological growth, all the other aspects of society (social structure, religion, morals, etc.) are much more dependent for their rates of change on cultural evolution which, as mentioned above, is very traditional and slow. This growing gap between the rate technological change and that of other parts of society has created ever mounting stresses and strains, and continues to do so as technological growth continues to accelerate. These problems break down into three main categories.

First of all, most aspects of society, being more bounded by traditional rates of cultural change, cannot keep up with and adapt to the rate of technological growth. All too often, new technologies are introduced without studying or trying to anticipate their long-range effects. An example of this is the birth control pill introduced in 1960. While the Pill did free women from being burdened with large numbers of children, which was the goal of its inventors, few, if any, people gave serious thought to how the Pill would change people’s attitudes toward sex and marriage, or how that would affect the status of women and the raising of future generations of children.

A second problem lies in the unbelievable destructive power of modern weapons, in particular hydrogen bombs. Before the industrial revolution, the destructiveness of war was largely proportional to the number of men directly engaged in it, and the number of those men was largely determined by the relatively low productivity of the pre-industrial societies that had to support them over time. This put distinct limits on how long and destructive wars could be, thus giving societies time to recover. Modern warfare, however, is by no means limited by such factors. A relatively few men can launch devastating destruction upon the planet totally out of proportion to their numbers. The technology of destruction has grown even faster than the technology of production, making total war as we understand it obsolete.

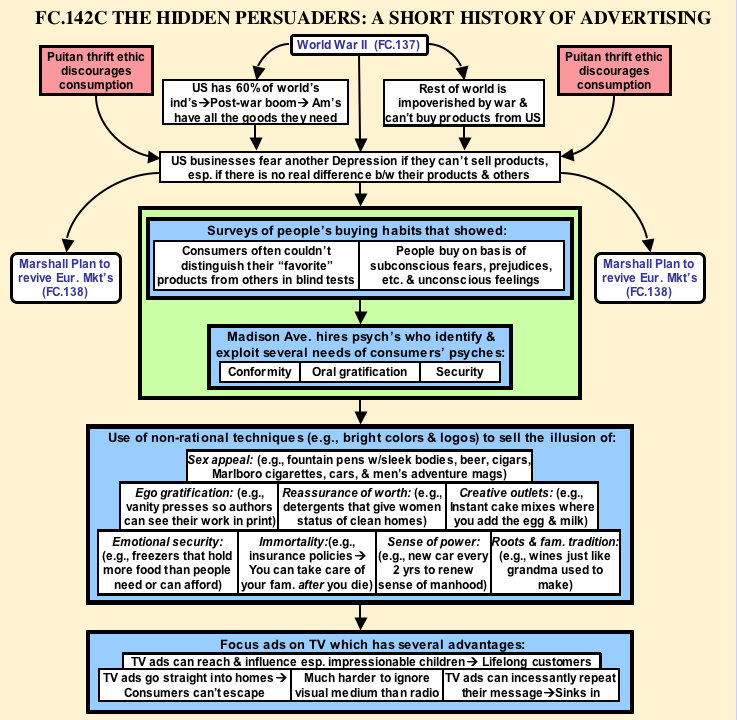

Finally, modern technology has transformed our economy from being mainly concerned with producing enough for everyone to being concerned with selling all it produces. This has spawned a pervasive culture of materialism and consumerism heavily influenced by advertising. Modern economies rely on more sales and consumption and sales to make the money to expand their production, which requires more consumption, and so on. Given the vastly larger population that is involved in this cycle and the ever growing levels of per capita consumption, there is no way the environment can support this level of growth.

All this adds up to a fairly grim prospect for the future. However, we are an ingenious and adaptable species that could very well see us successfully through our technological adolescence. For example, during the Cold War the United States and Soviet Union did manage to avoid a catastrophic third world war. While we are not out of the woods yet, there is still hope while there are still some woods left for us.

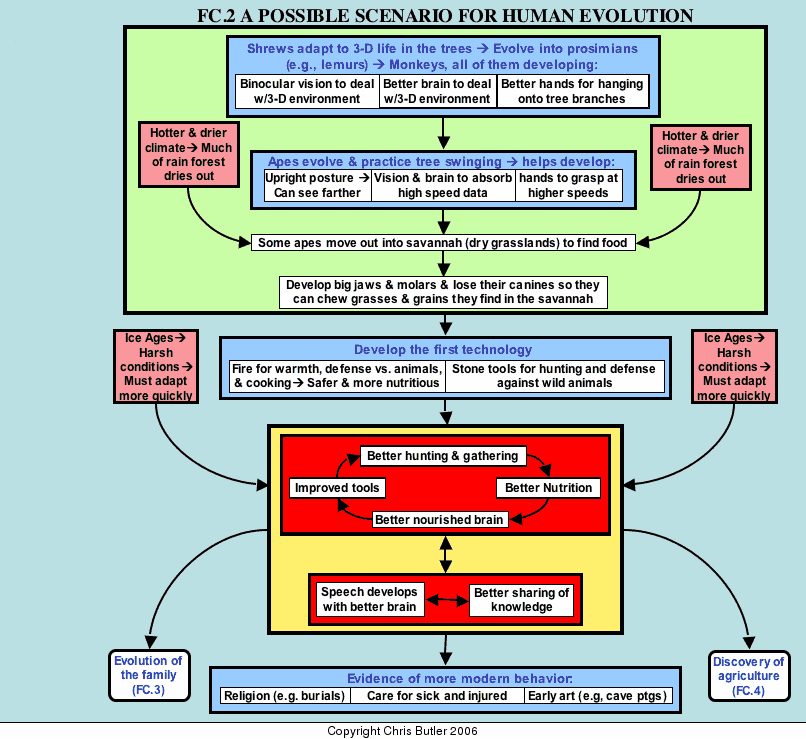

FC2A Possible Scenario of Human Evolution

Where to start?

While human history is primarily concerned with cultural and technological evolution, we need to understand a possible scenario for the evolution of the biological characteristics that have served as the basis for the human species’ other advances. Maybe a good starting point would be some 75,000,000 years ago. This is a mere drop in the bucket of time, but we have a long way to go before reaching anything closely resembling humans. We pick up our story with the lowly tree shrew.

The tree shrew, which appears quite similar to a mouse, hardly looks like anything we would like to call our ancestor. Yet scientists think this little creature was our connecting link with the lower forms of mammals. Converting this animal into a human would tax the skills of the most imaginative artist. It lacked binocular and color vision, upright posture, hands with opposable thumbs, a larger better-developed brain, and speech. In other words, it had none of the five characteristics that distinguish humans as a species. It also had to lose its tail, fur, and long snout.

The first critical step was moving into the trees away from intense competition on the ground. Life in the trees was more three-dimensional, involving accurately judging distances from branch to branch or else taking some nasty falls. This helped the development of binocular vision. Life in the trees also required hanging on to things to keep from falling. As a result, a primitive grasping hand started to evolve. Also, the more three-dimensional world of the trees required more awareness of things in all directions. This stimulated brain size and development.

Some 25,000,000 years later some tree shrews have evolved into the prosimians. These included the tarsier and ring-tailed lemur, which are often seen at the zoo and mistaken for monkeys. The prosimians resembled humans much more than the tree shrew, having binocular vision, shorter snouts, hands of a sort, and bigger brains. However, they still lacked erect posture and speech, while their brains, hands, and eyes fell far short of human standards. Some 40,000,000 years ago monkeys evolved from the prosimians. Although showing no obvious new developments toward human characteristics, they were more intelligent than prosimians and had better developed hands and eyes.

Next, we come to the apes, our closest cousins. Apes practiced one activity, tree swinging, that helped lead to human evolution in several ways. First of all, since tree swinging put the ape in an upright position, its head had to switch its position in order to see where it was going. A quadrupedal (four-legged) animal's head connects to the spine at the back of the skull. If we were to stand a dog on its hind legs, its head's normal position would have it looking straight up. The same was true for the still quadrupedal ape when it started tree swinging, making it more prone to crash into trees. Therefore, the ape's normal head position moved to connect to the spine at the base of the skull in order to adapt to this new tree swinging posture. This also paved the way for the later adaptation of erect posture that would free the hands for tool use. Speaking of the hands, tree swinging also led to more use and development of the hands giving apes better hand dexterity. The fairly rapid speeds at which apes swung also meant a lot of things came at them quickly and forced them to react quickly, thus leading to further brain development.

If apes had so much going for them, why did they not all evolve into humans? In general, one can say that evolution and natural selection are conservative and do not favor changes unless forced to by circumstances. This was especially the case with chimps, who had an easy niche in nature and felt no need to evolve. It was also true of gorillas whose great size let them stay pretty much the same. Timing was also important. Gibbons and orangutans were swinging in the trees for so long that their arms became over specialized for tree swinging and could not adapt well to life on the ground where our ancestors evolved. On the other hand, baboons came out of the trees too early and had not swung long enough to develop their upright posture. Thus they remained quadrupedal.

Out of the trees

Still, some three to five million years ago some apes did emerge from the trees into the African Savannah (grassland), and the question once again is why? The most likely answer is for food, and this is supported by the most plentiful and durable evidence we have from then: their teeth and jawbones. About this time their molars and jawbones got much bigger, suggesting they were eating lots of seeds and grains, which required massive jaws and molars to grind them up. This also meant that the canine teeth, their main defensive weapon in the harsh and dangerous Savannah, got in the way of chewing. Choosing between defense and eating, nature decided eating was more important and the canines were lost.

This of course created the problem of defense against predators. The solution seems to have been some sort of weapon. It was certainly nothing more than a stick, bone, or rock, but it apparently was effective. If it had not been effective we would not be here to talk about it. The importance of all this is that for the first time in the history of life on the planet, an animal was using a form of technology to extend its power dramatically and increase its chances of survival. The dawn of humans, or more properly, hominids had arrived.

The term hominids refers to modern humans (i.e., ourselves), our most direct ancestors, and collateral branches of our family tree that came to a dead end, such as the Neanderthals. . The earliest of these hominids, known as Australopithecines, lived from one to five million years ago. They were somewhat human in that they had better developed eyes, posture, hands, and brains than the apes. However, scientists do not generally call them humans because their brains were still much smaller than ours (about 450cc compared to around 1400cc for modern man). Their hands also had little or no precision grip, and they probably could not speak. Many see Australopithecines as the missing link between apes and humans.

There were several varieties of Australopithecines. The earliest, Australopithecus Afarensis, provided us with one of the most amazing discoveries in archaeology: forty percent of one skeleton. That may not sound like much, but it was unheard of to find that much of such an old skeleton intact. The scientist who found it, Donald Johansen, was so struck by this find that he even gave it the name Lucy after the Beatles song "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds."

Australopithecus Afarensis was the likely ancestor of two other branches of Australopithecines. One branch, the larger in size, was vegetarian. The other branch ate both meat and plants. The importance of this is that hunting for meat required more inventiveness than did collecting vegetation. As a result, the meat eaters developed tools (possibly including containers for better gathering) and weapons much more than the vegetarians did.

Eventually the meat eating Australopithecines evolved into what many scientists call the first true humans, Homo Habilis ("handy man") with a brain capacity of 650cc. They used and made very crude tools, although they still could not speak. For that reason, other scientists reserve the honor of the first humans for people known as Homo Erectus who had a brain capacity of some 750cc., which gave them the ability to speak.

Technological and cultural developments since the Australopithecines

A good deal of controversy surrounds the evolution of humans and their family tree. However, our evolution over the last million years has revolved increasingly around our technological and cultural innovations rather than biological changes. This is largely because on the one hand, biological changes are purely random, thus making evolution quite slow. However, technological and cultural changes are the products of more conscious and focused efforts to solve problems or create something. Therefore, such innovations happen at a much faster pace and accelerate the pace of change since they build upon previous efforts.

There were two main types of technological development our prehistoric ancestors came up with early on: flint tools and fire. Flint is unique among rocks because, when hit in the right way, it shatters, leaving very thin and razor-sharp pieces that can be worked into blades. Over time, as people spread to areas with little available flint or used up once plentiful supplies, they had to make more efficient use of this precious resource. At first, people were somewhat wasteful of it, maybe making only one hand ax out of a block of flint. It is estimated they got only 2-8 inches of blade for every pound of flint they used. Early Ice Age peoples came up with a method of knocking chips off of a piece of flint and using each chip for an ax or spearhead. As a result, they were able to get up to forty inches of blade per pound of flint. Their descendants would further refine this to get forty feet of blade per pound of flint.

Fire.

Of all the things that our ancestors invented or mastered to protect themselves from the harshness of the physical environment, none was more important than fire. As the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus wrote, it was the "brightness of fire that devises all” To the Greeks, it was the source of their crafts and civilization itself. It was what distinguished humans from the rest of the animal kingdom and gave them so much power; too much power as far as Zeus, king of the Greek gods was concerned.

The first people who mastered fire could use it, but probably not make it. As a result, they depended on natural sources such as a volcanoes or forest fires caused by lightning for their fire. Considering animals' natural fear of fire, we must admire the courage of that first individual who dared to pick up a burning ember and take it home. Once our ancestors had harnessed fire and found a way to keep it burning, they discovered some important uses for it.

The first use was probably for hunting and defense against wild animals, since it was obvious that animals feared fire. A common hunting technique would be to start a brush fire and use it to drive game toward other hunters or over a cliff. The value of fire for light and warmth soon became apparent, especially after our ancestors migrated out of Africa into the cooler climates of Europe and Asia. Fire could also harden sharpened sticks into better weapons. Finally, fire was useful for cooking food with several important results.

Cooked meat in particular held several advantages. The heat caused a chemical reaction that created proteins out of the amino acids in meat, thus making it more nutritious and leading to a healthier population. Fire also killed microbes in the meat, making it safer to eat. Finally, fire softened meat, making it possible for the very young and sick to chew it and thus be nourished. Altogether, cooking led to a healthier population that could grow and spread across the globe. We today are so concerned with overpopulation that we lose sight of how important and difficult it was to maintain a stable or growing population until very recently. Back then the average life expectancy was probably no more than twenty years, and half of all children died before the age of five. Thus extinction was a very real possibility. Cooking removed that possibility a bit.

The Ice Ages

Around 200,000 years ago, the planet started turning much colder. The cause of the ice ages is still unknown and subject of several theories including variations in the tilt of the earth's axis and its orbital path, continental drift, and clouds of cosmic dust blocking some of the sun’s radiation. Whatever the cause or causes, glacial sheets of ice moved south, covering much of the Northern Hemisphere. Summertime temperatures in England probably reached no more than 50 degrees Fahrenheit. By the same token, winters were horribly cold.

Such harsh conditions forced important changes in our ancestors and the various other life forms then. Keep in mind that physical adaptations were not planned or conscious. Rather, natural selection just accelerated the process whereby genetic mutations would be favored. What emerged was a whole new array of animals: giant cave bears, saber toothed cats, and woolly mammoths and rhinos to name a few. Our ancestors also went through some changes as well. Homo Erectus, as our prehistoric ancestors from then are called, had moved into cooler climates in search of game and living space. However, when the glaciers came, they were forced to adapt. What had been a fairly stagnant culture and species in stable conditions now changed at a relatively rapid rate. Even more rapid than their physical evolution was the evolution of their technology and culture.

Accelerated technological development

At this point, we see a cycle of technological development emerge to accelerate our evolution. Tool use stimulated brain development, which helped lead to more successful hunting and gathering. The improved diet and resulting brain development stimulated more tool development, better hunting, and so on. This basic feedback set in motion by hunting and tool use continued to repeat itself through the ages and is still at work today. Each new invention we come up with extends our power and also stimulates us to come up with more new inventions. This was a process that had started long before with the Australopithecines and continues now.

Speech

One of the effects of a bigger brain was the evolution of speech. This allowed both closer cooperation and more efficient sharing of information in such ventures as hunting. Therefore, each generation could easily learn the skills its ancestors had developed and perfected over the years instead of spending most of its time re-discovering them. This stimulated more brain development and ability to speak, encouraging more cooperation and sharing of knowledge, and so on. This feedback also fed back into and further accelerated the previous cycle of technological development, stimulating more sophisticated speech, etc.

However, there were severe limits to early humans' speech. For one thing, their pharynx, or voice box, did not drop enough to allow the full range of sounds we are accustomed to making now. As a result, their physical ability to speak was only about one-tenth of ours in terms of the sounds they could make and the speed at which they could make them. Their mental ability to speak was also severely limited. It takes a brain capacity of about 750cc to reach the ability to speak. Babies today reach that threshold between one and two years of age. Many prehistoric humans may never have reached that capacity. Or if they did reach the threshold of speech, they probably reached it much later in life than children today do. Combining that with their short life spans, prehistoric peoples had little time to develop anything profound to say, greatly impeding cultural and technological progress for a million years or so.

Better hunting and gathering technology. The Ice Ages also reduced the amount of vegetation available for gathering, thus increasing our ancestors’ reliance on hunting and develop more powerful weapons. When a better ability to speak combined with the process of each invention stimulating ideas for even more new inventions, a dramatic leap in technology and culture also took place. By 10,000 B.C.E., our ancestors, known as Cro Magnon but essentially Homo Sapiens Sapiens (i.e., ourselves) in a primitive setting, had learned to use other materials, notably wood, bone, and antler, in combination with flint, thus vastly expanding their range of tools and weapons compared to the crude and limited tool kit of the earliest hominids:

-

the use of bone, antler, and ivory for making tools that flint was unsuited for;

-

the sewing needle that led to warmer, better fitting clothes;

-

the spear which both extended the range and power of the hunter as a throwing weapon while maintaining a safe distance from dangerous animals when used as a hand held weapon;

-

barbed and grooved spearheads, which, being more deadly, led to better hunting;

-

the bolo for tripping up game;

-

the ability to make fire, giving them a stable source of warmth;

-

grooved air channels under the fire which led to hotter fires (which would lead to fired ceramics, which led to pottery and the kiln, and eventually to the furnace for smelting metals with all their contributions to civilization;

-

flint sickles, with bone or wood handles, which led to better gathering and a healthier population;

-

the burin, the first tool used for making other tools;

-

woven baskets, which also led to better gathering and more food;

-

fishing with spears, nets, and gorges (a type of hook), which led to a more stable food supply; and

-

crude shelters, built at first as wind breaks in the entrances of caves, and later as free-standing structures

Looking at all these inventions, Cro Magnons seem to tower over their ancestors, much as we see ourselves towering above them. This is deceptive, however, because we are building on what our ancestors built. Without the accomplishments of Cro Magnon and those who went before them, our own civilization could never have evolved.

All these new advances had profound implications for the future. For one thing, our ancestors’ larger brains would help lead to the development of the human family. Secondly, increasingly efficient hunting, gathering, and fishing made possible a more settled lifestyle, giving people time and opportunities to notice certain things around them, in particular the way seeds grow into plants. This revelation was the basis for the next great step in human evolution, the food producing revolution, or agriculture. Finally, better brain development and technology inspired and made possible new activities and behaviors that make the Cro Magnons seem much more modern to us.

Our ancestors’ behavior over the last 100,000 years or so also shows a much higher degree of intelligence than ever before. For example, they seem to have first realized the inevitability of death and created a religion to prepare for it. We have found people buried facing east and west, and also with the pollen of flowers in their graves. Our ancestors apparently worshipped the spirits of cave bears with whom they competed for living space. One Neanderthal cave has the skulls of some eighty bears arranged around it.

Prehistoric people also seem to have cared for their sick and infirm as evidenced by the skeleton of one man who lived to about forty years of age (old for back then) with the use of only one arm. They also apparently practiced female infanticide (killing female babies) as a form of population control. This is a comment not so much on our ancestors’ brutal nature as on the brutal conditions they had to deal with in order to survive. Not practicing such a measure might have meant extinction for the whole tribe or species.

Cro Magnons seem more modern to us culturally as well, especially in their art. In southern France and Spain they left a number of cave paintings that are amazing for their artistic touch and sensitivity. These paintings depict the various animals people then hunted. Their function may have been some sort of sympathetic magic in which portraying a successful hunt would cause a successful hunt. Whatever their purpose, these paintings are striking in the way they depict these animals in motion. They also can make us feel much more akin to these people we call our ancestors.

FC3A Possible Scenario for the Evolution of the Family and Gender Roles

The dramatic physical changes our ancestors experienced also triggered equally significant social changes that led to the evolution of the most basic social unit of our species: the family. One likely scenario involved two lines of development converging to create the family. First, as our ancestors moved out of the trees into the savannah in search of grains and grasses, they occasionally came across a carcass that they would pick clean for the meat. This casual scavenging gave them a taste for meat that developed into more intentional hunting. With the females tied down by the children, the males were generally the only ones free to hunt. Meanwhile the females and children would gather edible plants. Most likely, hunting was rarely successful, providing only about 10-20% of the food our ancestors ate, although the meat did provide valuable protein. The need to supplement the usually meager returns on their hunting may give us another clue as to why the males kept returning to the rest of the group. This pattern of food sharing created bonds vital to the evolution of the family.

Another development had to do with the evolution of a large brain and head which made the birthing process for humans more difficult. As a result, nature compensated by having human babies come to full term prematurely, making them among the most helpless animals at birth in all of nature. This greatly increased and prolonged children’s dependence on their mothers, who in turn needed protection and help getting food, especially in the harsh environment of the savannah.

The question is: why did males keep returning to the females and children? According to one theory, the answer lies in the evolution of year round mating in females to replace the seasonal estrus cycle that occurs in most mammals. The females who developed this pattern (by a purely random mutation) were better able to attract males to help them with food gathering and protection. As a result, more of their children survived to pass this characteristic on to future generations until it became the prevailing trait in humans.

Over time, these factors (year-round mating and food sharing) created permanent bonds that we have come to know as the family. Strengthening these bonds were two other factors. One was the added companionship and security of family life. We know, for example, that our prehistoric ancestors would feed and care for crippled members of their group despite their inability to contribute significantly to everyone else’s survival. Secondly, there was the emotional satisfaction that children gave their parents in terms of companionship, care in old age, and as an extension of themselves.

Gender differences in the species

For centuries there has been a controversy over the source of differences in male and female behavior and values within our species. Oftentimes described as the “Nature vs. Nurture” debate, it focuses on whether differences between men and women are the result of genetic or environmental factors. Coming largely from the Women’s Movement in the 1970s, the pendulum swung heavily to the side of nurture, the assumption being that aggressive tendencies in boys were the result of cultural factors and upbringing. The hope and belief was that if boys could be raised in an environment that didn’t stress aggression and violence, they would be no more aggressive than girls. Unfortunately, more recent research shows things are not quite that simple. While the environment is important in determining the way aggression is channeled, there are also inherent genetic factors influencing the equation. Testosterone levels in an individual are one factor. How men and women’s brains are structured is another. This may be the result of the hunting and gathering lifestyle our ancestors followed for the vast majority of our species’ existence and the different roles men and women played in it.

For men, who typically did the hunting, stalking and waiting for game required two main mental abilities: staying focused on one goal for long periods of time and keeping quiet during that prolonged period of waiting. This discouraged verbal socializing that could scare off any game. Nature would favor males whose brains were adapted to these qualities by awarding them successful hunts while killing off the more chatty ones through unsuccessful hunting and starvation.

Women, who performed very different tasks, required very different qualities. While looking for and gathering any edible vegetation, they also might have to keep track of several children and look out for predators. Unlike men, who had to stay quiet, those women who cooperated with one another (especially in looking out for one another’s children) and communicated verbally would be much more successful than women who operated quietly and independently of one another. For one thing, the sound of a number of women talking might be enough to scare off some potential predators. Such cooperation and communication would also create strong social bonds between the women, providing much of the glue that has kept societies together down through the ages. And just as nature would favor men with brains adapted to focus quietly on one goal, it would favor women whose brains were more adapted to verbal socializing and keeping track of several things at once.

Indeed, recent research has shown that men and women’s brains are largely structured in those ways. Women will typically use five times as many words in a situation as men will. Also, while men will listen with just one side of their brains, women will use both sides, indicating more of a talent for multi-tasking. It is important to note that these are general, not absolute, tendencies in men and women. Within each gender there is a wide range of differences between individuals, thus creating a large gray area that one certainly could not describe as absolutely male or female. Thus one should not use these general tendencies as supporting a “biology is destiny” argument for locking men and women into certain rigid roles. By the same token, these are tendencies we cannot afford to ignore in discussing issues of gender differences.

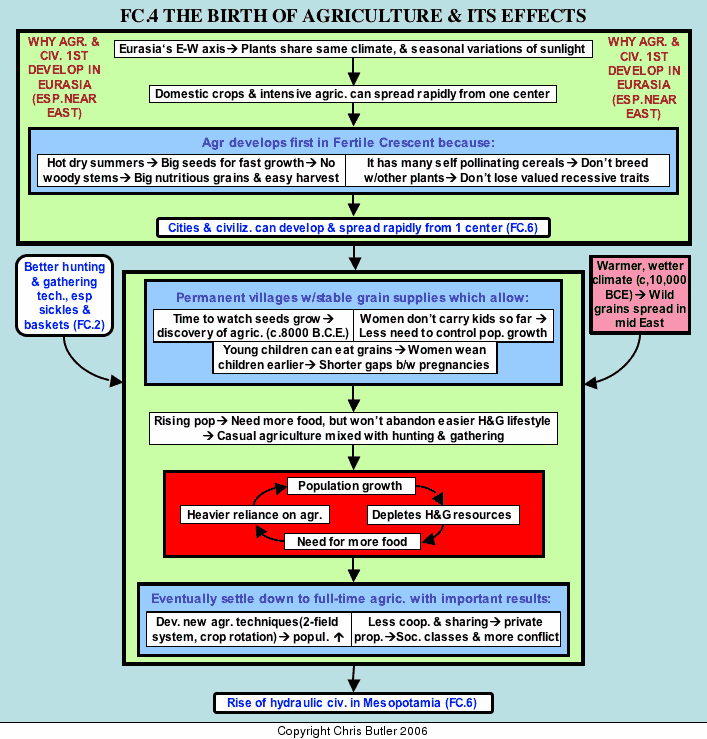

FC4The Birth of Agriculture and its Effects

Cursed is the ground for your sake; in sorrow shall you eat of it all the days of your life. Thorns also and thistles shall it bring forth to you; and you shall eat the herb of the field. In the sweat of your face shall you eat bread till you return to the ground; for out of it were you taken; for dust you are, and unto dust you shall return.(Genesis)

Introduction

Some 10,000 years ago, only 5-10,000,000 people inhabited the planet, certainly no more. Our ancestors’ technology had taken them a long way, but they still lived as part of nature, not in any way as its master. They did not realize it, but the last one per cent of our existence so far would see unbelievable changes sweep across the planet and change its face forever. Humanity stood on the verge of over-running the earth with vast numbers of its species. Supporting those vast numbers was possibly the greatest revolution in our history: agriculture, the ability for people to produce their own food supply. The agricultural revolution had two parts: the domestication of plants and the domestication of livestock.

Why Eurasia and Mesopotamia?

Starting with the birth of agriculture most of history’s major developments have taken place in the vast land mass known as Eurasia and extending across the Mediterranean and North Africa. Europeans who dominated the globe in the late 1800s and early 1900s claimed religious, cultural, and even biological superiority as the basis for their predominance. While such ideas hold little favor today, there still remains the question of why Asia and Europe have held central place in the history of civilization. Much of the answer probably rests in geographic and biological factors.

The underlying factor is that Eurasia lies along an East-West axis in mostly temperate zones. In contrast, Africa and the Americas are oriented from north to south and thus straddle a variety of climates. As a result, crops found in Eurasia are more adapted to the same diseases, climate, and seasonal variations in sunlight (which determine when plants germinate, flower, and bear fruit). Therefore, domesticated crops and intensive agriculture can spread more rapidly across Eurasia than they can across the vastly different climactic zones in Africa and the Americas. For example, because of intervening tropical zones, the cultivation of corn in the Temperate Zone of Mexico in the northern hemisphere never spread to Peru in the southern hemisphere until after 1500 when Europeans conquered both regions. Similarly, crops adapted for temperate zones in northern parts of Africa did not reach the southern tip of Africa until Dutch settlers introduced them in the 1600s.

Of course, there are also topographical and even climactic barriers within Eurasia, such as the Tibetan Plateau, Himalayan Mountains, and Asian steppes isolating East Asia from the rest of Eurasia. Therefore, agriculture probably developed independently in China and spread from there to Southeast Asia, Korea, and Japan. However, despite topographical barriers, the similar climates of East Asia and the western half of Eurasia ultimately allowed crop sharing in both directions, thus helping both civilizations advance more quickly.

Why Mesopotamia?

More specifically, it was Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) where agriculture first evolved in Eurasia and then spread westward across North Africa and Europe and eastward to the Indus River Valley. Environmental factors favored this specific region as the birthplace of agriculture. First of all, Mesopotamia, and the Middle East in general, have cool rainy winters and hot dry summers, encouraging plants, especially cereals, to develop large seeds for rapid growth in the limited growing season. This produces relatively small plants without woody stems, which, in turn leads to cereals with lots of large seeds (i.e., more food) that are easy to harvest (without woody stems).

Another factor is that Mesopotamia has many self-pollinating crops (six of them exclusive to that area) that can reproduce without pollination with other plants. The importance here is that recessive traits that are vital to farming but harmful to the plant in nature do not get bred out of the plant through cross-pollination. For example, along with the dominant trait for grains and pea pods to shatter in order to spread their seeds is a recessive trait for a few plants not to shatter. This made it easier for people to harvest them, plant more of them next season, and spread the varieties with the normally harmful tendency not to shatter.

Along with the spread of agriculture from Mesopotamia, other ideas and technologies could spread as well, leading to the relatively rapid development and spread of civilization across Eurasia compared to other regions of the globe whose environments prevented or greatly slowed down such exchanges. And, of course, after the impetus started by Mesopotamia, the exchange of new ideas became two-way, further accelerating the rise and spread of civilization in Eurasia.

The invention of agriculture

In addition to factors unique to Mesopotamia,two other converging factors led to the domestication of plants. First, better hunting and gathering technology provided a more stable food supply. Second, warmer and wetter conditions in the Near East at the end of the last Ice Age about 10,000 years ago led to the spread of cereal grains. Together these provided more stable food supplies that allowed people to settle down in more permanent villages. These villages produced two very different effects that together helped lead to the discovery and triumph of agriculture.

One was a growing population that needed more food than the hunting and gathering lifestyle could supply. This may have been partly due to earlier weaning of the young. Since women in hunting and gathering societies were always on the move, they could deal with only one highly dependent child at a time. Therefore, so they have only one small child to carry at a time, they would nurse their young up to age four to interrupt their fertility until their youngest child was less dependent on the mother. More settled village life made such strict birth control less mandatory, allowing earlier weaning and a higher birth rate as a result.

Settled village life also was gave people the opportunity to watch seeds in one place for a long time and notice how seeds grow into plants. Exactly how and when this happened is not known, but women probably made this discovery since they gathered the seeds and had more opportunity to notice how they sprouted and grew. Possible scenarios of this discovery include seeds spilled near camp or a wet grain supply sprouting and growing. However it happened, the realization of the potential of this discovery was probably gradual.

So was the transition to a completely settled agricultural lifestyle. While later civilizations would see agriculture as a gift of the gods, hunting and gathering peoples, such as the early Hebrews quoted above, saw it as a curse since it involved much more work and went against the traditional ways of life they had followed for countless generations. Whereas tradition today is generally shoved aside and scorned, we should keep in mind that until very recently, it was a major force in people's lives. They did not take change so lightly as we do since it disrupted the fragile stability of their lives. So the question arises as to why did people turn to farming.

The most likely explanation was they had to. For a long time after the discovery of agriculture, people continued to follow a hunting and gathering lifestyle mixed in with some casual agriculture, such as scattering seeds along a riverbank or in a field and coming back in a few months to harvest it. This did improve the food supply, and dramatically increased the number of people that could be supported. Even the primitive agriculture practiced then could support up to fifty times more people than hunting and gathering could. However, those extra people put a growing strain on the natural environment’s ability to feed them. One solution was to expand the agriculture. Of course, that led to more food and more population, causing even more strain on the natural food supply and leading to further expansion of the agriculture. In time, both men and women had to devote more and more time to tending the crops and less time to their traditional hunting and gathering ways. Eventually, they settled down and became full-time farmers.

Settled agricultural life had dramatic effects on human society and the environment. First of all, farming required less cooperation and sharing than hunting and gathering did. Before, all members of a tribe had to hunt together and share the results. Since there was no private property or anything to fight over, hunting and gathering societies were (and still are) relatively peaceful and harmonious. In contrast, agriculture allowed individual families to farm their own lands. As a result, private property evolved which led to social classes and more conflict in society between rich and poor.

New agricultural techniques, which replaced the more primitive slash and burn agriculture, also had their effects. The two-field system, which left one field fallow each year to replenish the soil, and crop rotation, which used different crops to take different nutrients out of the soil, reduced soil exhaustion. Both of these, combined with one other technique, irrigation, also created a surplus of grain and the need for a high degree of organization and cooperation. That surplus and level of organization in turn would lead to the rise of the first cities and civilizations with specialized crafts and technologies such as writing and metallurgy.

In the process of farming, our ancestors also inadvertently disrupted natural selection. There were two varieties of wheat they collected on the hillsides of the Near East. The dominant type shattered upon the slightest touch, scattering the seeds so the species could spread and survive. The other, recessive type, did not scatter its seeds so easily, and thus was harder to find. However, it was easier to harvest since the seeds did not scatter. As a result, a higher proportion of this variety was collected and planted than occurred in nature. With each succeeding year a higher proportion of the non-scattering wheat was harvested and planted. Natural selection had been reversed.

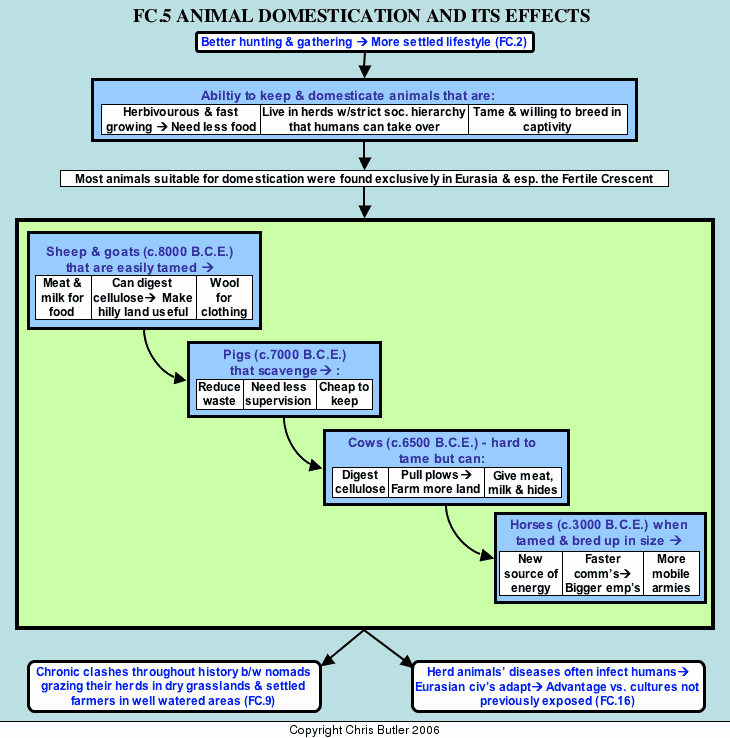

FC5The Domestication of Animals and its Effects

About the same time as the invention of agriculture (c.8000 BC) another revolution occurred: the taming of wild animals for domestic use. As with agriculture, the more settled lifestyle that better hunting and gathering allowed at the end of the last Ice Age was important, because it gave people the time and opportunity to keep and domesticate animals.

However, while animals of many different species have been tamed and kept as pets by humans, only a very few have been big enough (100 pounds or more) to be useful as sources of food and labor while meeting three basic criteria for true domestication. First, they must be herbivorous (plant eaters) and fast growing so they use up a minimum of our food resources and quickly become useful to us as a food source. Herbivores directly convert the plants they eat into meat, while carnivores require at least one extra level (i.e., other animals) in the food chain to survive. Therefore, pound for pound, it will take up to ten times as much plant nutrition to raise and support a carnivore as it does to for an herbivore.

Secondly, animals suitable for domestication should live in herds or packs with a strict social hierarchy of which humans can assume leadership. The third criterion for domestication is that animals must be easy to tame and willing to breed in captivity. This also rules out most carnivores, who are typically aggressive hunters and less easily domesticated than herbivores. An obvious exception is dogs who, being relatively small, must hunt cooperatively in packs, making them more social and easy to domesticate.

As with agricultural plants, what few animal species that are suitable for domestication are found predominantly in Eurasia and especially in what we call the Middle East of the Fertile Crescent. There were five such animals. The first two of these to be domesticated were sheep and goats, largely because they were the most docile and easy to tame. Sheep provided meat, milk, and fur. They also were ruminants, which meant they could digest the cellulose from grass, thus making previously useless land (e.g., rocky hillsides) useful.

As with plants, our ancestors also tampered with natural selection, using selective breeding to produce animals that were fat, meaty, slow, and with long wool rather than fur that is shed seasonally, qualities that are useful for us but normally harmful to a species in the wild. Eventually, this process would produce sheep and goats that differed considerably from their cousins in nature.

The next animal domesticated was the pig (c.7000 BC). Unlike sheep and goats, the pig was not a ruminant and providing no milk or fur. However, pigs did provide meat and, being scavengers, had several advantages. Whether scavenging in the local woods or city streets, they were cheap to keep. They also needed little or no supervision, making them easy to keep compared to flocks of sheep and goats that needed constant shepherding. Finally, until very recently, towns and cities rarely had proper sanitation facilities, making them extremely unclean and unhealthy. Pigs scavenging in the streets helped keep them a little cleaner. In fact, many towns had laws protecting them, despite their mean dispositions and occasional habit of attacking children.

Cattle were next (c.6500 BC), which gave milk, meat, hides, and could eat grass. However, they were bigger, wilder, and tougher to tame than sheep, goats, and pigs, causing some civilizations, such as the Minoans on Crete, to see the bull as a symbol of power. Probably the most innovative use for the cow was to hitch it up to a plow, tapping a non-human energy source that increased the power at our disposal and the amount of land under cultivation many times over. However, the earliest farmers hitched the plow up to the cow's horns, not the most efficient use of its power.

Somewhat later (c.3000 BC), horses were domesticated with three far-reaching effects. First of all, they could be used as a source of labor like cattle although their full potential wouldn’t be tapped until the invention of the horse-collar (c.900 AD) which pulled from the chest rather than the neck. Secondly, mounted warfare made armies much more mobile, dangerous, and destructive. This was especially true of nomadic horsemen who would occasionally be the scourge of richer and more sedentary civilizations. Finally, mounted messengers dramatically quickened communications, making it possible to keep in touch with and rule much larger empires.