The RenaissanceUnit 11: The Renaissance

FC74The invention of the printing press and its effects

Introduction

At the height of the Hussite crisis in the early 1400's, when the authorities ordered 200 manuscripts of heretical writings burned, people on both sides realized quite well the significance of that act. Two hundred handwritten manuscripts would be hard to replace. Not only would it be a time consuming job, but also trained scribes would be hard to find. After all, most of them worked for the Church, and it seemed unlikely that the Church would loan out its scribes to copy the works of heretics. Although the Hussites more than held their own against the Church, their movement remained confined mainly to the borders of their homeland of Bohemia. One main reason for this was that there was no mass media, such as the printing press to spread the word. A century later, all that had changed.

Like any other invention, the printing press came along and had an impact when the right conditions existed at the right time and place. In this case, that was Europe in the mid 1400's. Like many or most inventions, the printing press was not the result of just one man's ingenious insight into all the problems involved in creating the printing press. Rather, printing was a combination of several different inventions and innovations: block printing, rag paper, oil based ink, interchangeable metal type, and the squeeze press.

If one process started the chain reaction of events that led to the invention of the printing press, it was the rise of towns in Western Europe that sparked trade with the outside world all the way to China. That trade exposed Europeans to three things important for the invention of the printing press: rag paper, block printing, and, oddly enough, the Black Death.

For centuries the Chinese had been making rag paper, which was made from a pulp of water and discarded rags that was then pressed into sheets of paper. When the Arabs met the Chinese at the battle of the Talas River in 751 A.D., they carried off several prisoners skilled in making such paper. The technology spread gradually across the Muslim world, up through Spain and into Western Europe by the late 1200's. The squeeze press used in pressing the pulp into sheets of paper would also lend itself to pressing print evenly onto paper.

The Black Death, which itself spread to Western Europe thanks to expanded trade routes, also greatly catalyzed the invention of the printing press in three ways, two of which combined with the invention of rag paper to provide Europe with plentiful paper. First of all, the survivors of the Black Death inherited the property of those who did not survive, so that even peasants found themselves a good deal richer. Since the textile industry was the most developed industry in Western Europe at that time, it should come as no surprise that people spent their money largely on new clothes. However, clothes wear out, leaving rags. As a result, fourteenth century Europe had plenty of rags to make into rag paper, which was much cheaper than the parchment (sheepskin) and vellum (calfskin) used to make books until then. Even by 1300, paper was only one-sixth the cost of parchment, and its relative cost continued to fall. Considering it took 170 calfskins or 300 sheepskins to make one copy of the Bible, we can see what a bargain paper was.

But the Black Death had also killed off many of the monks who copied the books, since the crowded conditions in the monasteries had contributed to an unusually high mortality rate. One result of this was that the cost of copying books rose drastically while the cost of paper was dropping. Many people considered this unacceptable and looked for a better way to copy books. Thus the Black Death rag paper combined to create both lots of cheap paper plus an incentive for the invention of the printing press.

The Black Death also helped lead to the decline of the Church, the rise of a money economy, and subsequently the Italian Renaissance with its secular ideas and emphasis on painting. It was the Renaissance artists who, in their search for a more durable paint, came up with oil-based paints. Adapting these to an oil-based ink that would adhere to metal type was fairly simple.

Block printing, carved on porcelain, had existed for centuries before making its way to Europe. Some experiments with interchangeable copper type had been carried on in Korea. However, Chinese printing did not advance beyond that, possibly because the Chinese writing system used thousands of characters and was too unmanageable. For centuries after its introduction into Europe, block printing still found little use, since wooden printing blocks wore out quickly when compared to the time it took to carve them. As a result of the time and expense involved in making block prints, a few playing cards and pages of books were printed this way, but little else.

What people needed was a movable type made of metal. And here again, the revival of towns and trade played a major role, since it stimulated a mining boom, especially in Germany, along with better techniques for working metals, including soft metals such as gold and copper. It was a goldsmith from Mainz, Germany, Johannes Gutenberg, who created a durable and interchangeable metal type that allowed him to print many different pages, using the same letters over and over again in different combinations. It was also Gutenberg who combined all these disparate elements of movable type, rag paper, the squeeze press, and oil based inks to invent the first printing press in 1451.

The first printed books were religious in nature, as were most medieval books. They also imitated (handwritten) manuscript form so that people would accept this new revolutionary way of copying books. The printing press soon changed the forms and uses of books quite radically. Books stopped imitating manuscript forms such as lined paper to help the copiers and abbreviations to save time in copying. They also covered an increasingly wider variety of non-religious topics (such as grammars, etiquette, and geology books) that appealed especially to the professional members of the middle class.

By 1482, there were about 100 printing presses in Western Europe: 50 in Italy, 30 in Germany, 9 in France, 8 each in Spain and Holland, and 4 in England. A Venetian printer, Aldus Manutius, realized that the real market was not for big heavy volumes of the Bible, but for smaller, cheaper, and easier to handle "pocket books". Manutius further revolutionized book copying by his focusing on these smaller editions that more people could afford. He printed translations of the Greek classics and thus helped spread knowledge in general, and the Renaissance in particular, across Europe. By 1500, there were some 40,000 different editions with over 6,000,000 copies in print.

The impact of the printing press

The printing press had dramatic effects on European civilization. Its immediate effect was that it spread information quickly and accurately. This helped create a wider literate reading public. However, its importance lay not just in how it spread information and opinions, but also in what sorts of information and opinions it was spreading. There were two main directions printing took, both of which were probably totally unforeseen by its creators.

First of all, more and more books of a secular nature were printed, with especially profound results in science. Scientists working on the same problem in different parts of Europe especially benefited, since they could print the results of their work and share it accurately with a large number of other scientists. They in turn could take that accurate, not miscopied, information, work with it and advance knowledge and understanding further. Of course, they could accurately share their information with many others and the process would continue. By the 1600's, this process would lead to the Scientific Revolution of the Enlightenment, which would radically alter how Europeans viewed the world and universe.

The printing press also created its share of trouble as far as some people were concerned. It took book copying out of the hands of the Church and made it much harder for the Church to control or censor what was being written. It was hard enough to control what Wycliffe and Hus wrote with just a few hundred copies of their works in circulation. Imagine the problems the Church had when literally thousands of such works could be produced at a fraction of the cost. Each new printing press was just another hole in the dyke to be plugged up, and the Church had only so many fingers with which to do the job. It is no accident that the breakup of Europe's religious unity during the Protestant Reformation corresponded with the spread of printing. The difference between Martin Luther's successful Reformation and the Hussites' much more limited success was that Luther was armed with the printing press and knew how to use it with devastating effect.

Some people go as far as to say that the printing press is the most important invention between the invention of writing itself and the computer. Although it is impossible to justify that statement to everyone's satisfaction, one can safely say that the printing press has been one of the most powerful inventions of the modern era. It has advanced and spread knowledge and molded public opinion in a way that nothing before the advent of television and radio in the twentieth century could rival. If it were not able to, then freedom of the press would not be such a jealously guarded liberty as it is today.

FC75The Economic recovery of Europe (c.1450-1600)

The turmoil of the Later Middle Ages (c.1300-1450) continued and accelerated the changes that started with the rise of towns and kings in the High Middle Ages (c.1100-1300). Although these were certainly difficult times to live through, they also paved the way for the modern institutions, movements, and values that would emerge after 1450: capitalism with its new attitudes toward money and profit, the Renaissance with its new attitudes toward the secular world and Man's place in it, the nation state with its relatively centralized bureaucracy and army, and the age of exploration with the new perspective it gave on Europe's place in the world. New technological innovations such as the printing press, gunpowder, and better ships and navigation would also generate significant changes.

Social changes

The turmoil of the Later Middle Ages did not affect everyone equally. Nobles, in particular, saw a decline in their position as a class. The longbow, gunpowder, and massed formations of infantry pikemen effectively challenged the armored knight's supremacy on the battlefield. Even his place in the castle grew ever more dangerous as new and more destructive cannons were constantly being developed. Economically, the Later Middle Ages had seen labor shortages that led to higher prices. Inflation cut increasingly into the noble's wealth since it was based on land with a more static value. By 1450, almost all the peasants in Western Europe had been able to buy freedom from their lords, paying them fixed rents instead of labor. Even those rents failed to help the nobles much since inflation reduced their value and nobles often had little skill or desire to spend within their means.

The nobles' decline meant other social classes could rise in power and status. Peasants benefited because they had bought their freedom and many even owned their land. The greater incentive provided by working for themselves rather than their lords led to greater agricultural production and the revival of Europe's population. The middle class benefited by making money from the nobles, either through loans with interest or selling them goods for a profit. However wealthy nobles may have been, it seemed that a lot of their money was ending up in the hands of middle class merchants. The middle class was also assuming a larger role in the governments of the emerging national monarchies in Western Europe. Kings also benefited since the nobles had been the main obstacles to building strong nation-states. The alliance of kings and middle class meant that the kings were the only ones with the power and wealth to afford the new gunpowder technology that was becoming a necessary part of any respectable army.

In spite of this, some powerful and influential nobles remained. Others were forced to seek employment in the king's army or at his court as courtiers, basically idle hangers on whose job was to make the king's court look impressive. Many others lost their noble status by having to support themselves through such ignoble pursuits as agriculture and commerce. Still, the nobles were considered the class to belong to. As a result, we see wealthy members of the middle class buying titles of nobility from the king (who always needed cash), giving up their businesses, and settling down on their landed estates just like other nobles. In this way, the noble class was constantly replenished by new blood, although the importance of the nobles kept on its path of gradual decline. The changes sweeping through European society were making it harder and harder to find a place for the nobles.

By 1500, we see the peasants in Western Europe free and often in possession of their own land. The middle class' status was getting steadily higher, both through their money and positions in the king's bureaucracy. And the kings were tightening their grip on their realms through their bureaucracies and armies.

Economic revival

, as usual, was based firmly on agriculture revival. That largely depended on the climate, which improved during this period, but other factors also helped. For one thing, the turmoil of the Later Middle Ages, which had weakened the Church and Nobles, was largely subsiding by 1450. This led to the emergence of strong monarchies in Western Europe that could safeguard the peace and promote trade and commerce. Secondly, the nobles, ruined by inflation and the collapsed urban grain market triggered by the Black Death, had sold most of their serfs their freedom by 1450. Finally, the peasants who had survived the Black Death and inherited the property of those who died had attained a higher standard of living. The fact that most peasants were now free and that many owned their land provided incentive to work harder that led to better agricultural production. One good indication that this was taking place was the fact that Europe's population rose from an estimated 50 million in 1450 to 70 million by 1500. This revival had three effects that would combine to create a dynamic new economic system: capitalism.First of all, the dramatic population growth of the late 1400's meant that towns and trade could also rapidly recover and surpass their previous prosperity. In 1450, the wealthiest banking family in Europe was that of the Medici of Florence, whose fortune consisted of 90,000 florins. By the 1500's, another banking family, the Fuggers of Augsburg in Germany, had taken over first place with nearly one million florins to their credit, over ten times that of the Medici half a century before. What this suggests is that the amount of trade and money in circulation had increased a great deal.

The second effect was that there were new consumer markets, but with a very different distribution of wealth from before. In the High Middle Ages, nobles had provided merchants with much of their market since they controlled so much of Europe's wealth at that time. By 1450, this had changed. Most nobles had lost money and status and could not afford the fine woolens and other goods made by the guilds. Instead there were common laborers and peasants, each with a modest amount of money to spend. A lot of money was there. It was just spread out more widely.

This change in the consumer market from a few rich nobles to a large number of people each with modest amounts of cash led to a change in production techniques as well. Up to this point, guilds had controlled the production and selling of manufactured goods, while nobles could afford the high quality and prices that the guilds maintained. The new type of consumer emerging by 1500 could not afford them. In response to this, some wealthy businessmen went outside the town walls and the jurisdiction of the guilds to the various peasant cottages in the countryside. Here the peasants would produce lower quality woolens than the guilds produced. The businessmen would pay them lower prices for those woolens and turn around and undersell their guild competitors. In this way, older medieval cities and guilds, such as in Flanders, went into decline, while other centers of production took their places. This also led to the growing concentration of wealth in the hands of a few rich businessmen instead of being spread out among the guilds. Thus by 1500, the consumer market was more spread out than before, while the means of production and investment were concentrated in fewer hands.

The third effect of Europe's reviving economy was that its expanding internal markets prompted Spanish and Portuguese explorers to search for new trade routes to the sources of spices in the Far East. Besides opening up whole new continents for discovery and exploration, this also vastly expanded the volume of Europe's trade.

New business techniques

In order to handle this higher volume of trade, new techniques of handling money became prevalent about this time. The Italian city-states especially pioneered these new methods. The prosperity that these new business techniques brought Italy largely explains why Italy would lead the rest of Europe in the Renaissance. Very briefly, these techniques were:

-

Joint stock companies. These allowed people with small amounts of cash to take part in business enterprises such as merchant expeditions. Their importance was that, instead of hoarding their money, people put it into circulation in Europe's economy, allowing it to grow even more.

-

Insurance companies. These reduced the risk of losing all of one's investment in a business venture. The result was much like that of joint stock companies, in that it encouraged people to invest, rather than hoard, their money, which stimulated further growth in Europe's economy.

-

Deposit banks and credit. These gave bankers more money to invest in business ventures since they attracted investors with their promise of guaranteed interest from the deposits. Banking houses also opened branches and extended a system of credit across Western Europe. Credit allowed a businessman to use more money than he actually had to embark on some venture, paying his creditor back with interest when he made his profit. Europe's economy grew much more quickly this way than if it had been limited by the amount of cash on hand at any particular time. Banking and credit also made the transfer of funds across Europe much safer. For example, with a strictly cash economy, someone transferring funds from Florence to London ran the risk of being ambushed by brigands and losing his money. With credit, the same merchant could send an agent to London with a note saying he was worth so much money guaranteed by the bank back in Florence. The agent might get that money in the form of church taxes bound for Italy. He could use that cash in England, and then send a credit note back to Florence worth the amount he borrowed in Church taxes. If brigands ambushed an agent either way, all they got was a credit note that they could not spend. Meanwhile, the Florentine banker got hold of all the funds he needed in England, and the Church in Italy safely collected its taxes from England.

There were dangers to this system, especially debtors not repaying their creditors. Kings were especially bad risks in this respect. For example, in the 1340's, Edward III of England failed to repay the Bardi and Peruzzi firms of Florence. This caused their bankruptcies, which sent ripples throughout Western Europe's economy since so much of it was tied up with these two banking houses.

These new business techniques combined to create a feedback cycle that accelerated the growth of Europe's economy. More money was invested in new business ventures. This increased trade, which stimulated more production of goods. That, in turn, created more jobs for people, who had more money to spend, which was safer because of the new business techniques, and so on.

Overall, the system worked quite well, providing money for the expansion of Europe's economy and the growth of its monarchies. Two other important factors should be mentioned. One is the dramatic improvement in mining techniques in Europe at this time. Germany in particular saw a fivefold increase in mining production between 1400 and the early 1500's, which put much more silver into circulation. Secondly, the adoption of Arabic numerals improved accounting techniques so trade and business could run more efficiently. All this increased economic activity and prosperity transformed European values and attitudes toward money and helped create a new economic system called capitalism.

Capitalism

is an economic activity that involves using large sums of money or capital in large-scale commercial, manufacturing, or agricultural activities. It had some medieval roots, but also some non-medieval elements that did not develop until around 1500. We can isolate four main characteristics of capitalism:-

Private ownership of the means of production. This was largely a break from the Middle Ages when guilds controlled the means of production. We have seen how wealthy businessmen started to break the guilds' monopoly by having peasants produce textiles in the countryside. This process continued and accelerated after 1500. Modern communism theoretically has the means of production owned by the workers, represented by the government, which in some ways seems closer to medieval guilds than its main rival, capitalism.

-

The law of supply and demand determines prices. Once again, this is a break from the guilds which kept prices artificially fixed no matter how plentiful or scarce its goods were. Communist governments also control prices in a similar way.

-

There is a sharp distinction and often little contact between the workers and the capitalist who owns the means of production. Such a distinction existed to a much smaller degree between guild masters and their laborers, and this became a serious problem in the later Middle Ages. Such a gap between capitalists and their workers would widen considerably and become especially bad in the early Industrial Revolution of the 1800's.

-

The profit motive. Although medieval guilds and merchants made profits, those profits were largely restricted by the Church's ban against charging more than a "fair price" for goods and services. The emergence of the profit motive by 1500 especially shows the changing attitudes and values in European civilization.

Capitalism helped lay the foundations for the rise of national monarchies in Europe by providing them with the capital to build up strong professional armies and bureaucracies. The states that best adapted to capitalism, in particular the Dutch Republic in the 1600's and England in the 1700's, would emerge as the economic and political powerhouses of Europe and eventually establish dominance of the world in later centuries. European prosperity in the later 1400's also made patronage of the arts possible and helped create one of the greatest cultural movements in history: the Renaissance.

FC75AThe Birth of Banking

One of history’s most important financial innovations was banking, which was closely bound up with credit. The main problem spurring on this development was the need to safely transport large amounts of cash over long distances in order to carry on trade across Europe. Such journeys were particularly beset by two dangers: natural disasters, especially storms, and attacks by pirates or brigands. Luckily, there were two parties with complementary needs that led to a solution. One was the Church, which needed to send its taxes to Italy from all over Europe. The other consisted of Italian merchants who wanted to take money from Italy to destinations across Europe in order to carry on trade.

At some point, a merchant started sending agents to other countries to trade. However, instead of carrying cash, they had letters of credit that they would present to local Church officials in return for cash that they could use there for trading. When they or church officials returned to Italy, they would bring letters of credit worth the amount borrowed from the Church and present them to the Italian merchant who would then give the church the money he owed them. In that way, both parties could transfer large amounts of money across Europe without carrying any cash.

As this practice caught on, there were other people who wanted to transfer funds across Europe without the risks that came from traveling with cash. Therefore, they would deposit cash with a merchant who had branch offices all over Europe, take a letter of credit to their destination, and reclaim their cash from the merchant’s branch office there. Naturally, the merchant would charge a fee for this service. He would also use the money deposited with him for his own business deals, hopefully making a profit on the depositor’s cash before he reclaimed his money. Thus was born our modern institution of banking, an essential ingredient in the capitalist system.

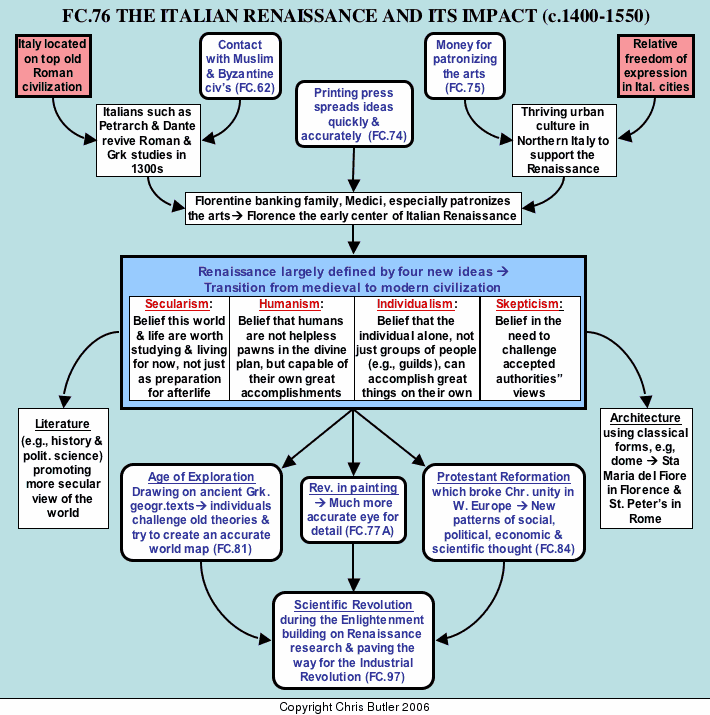

FC76The Italian Renaissance (c.1400-1550)

...everything that surrounds us is our own work, the work of man: all dwellings, all castles, all cities, all the edifices throughout the whole world, which are so numerous and of such quality that they resemble the works of angels rather than men. Ours are the paintings, the sculptures; ours are the trades sciences and philosophical systems.— Gianozzo Manetti, 1452

Introduction: why Italy?

On rare occasion one comes across a period of such dynamic cultural change that it is seen as a major turning point in history. Ancient Greece, and especially Athens, in the fifth century B.C. was such a turning point in the birth of Western Civilization. The Italian Renaissance was another. Both were drawing upon a rich cultural heritage. For the Greeks, it was the ancient Near East and Egypt. For the Italian Renaissance, it was ancient Rome and Greece. Both ages broke the bonds of earlier cultural restraints and unleashed a flurry of innovations that have seldom, if ever, been equaled elsewhere. Both ages produced radically new forms and ideas in a wide range of areas: art, architecture, literature, history, and science. Both ages shined brilliantly and somewhat briefly before falling victim to violent ends, largely of their own making. Yet, despite their relative briefness, both ages passed on a cultural heritage that is an essential part of our own civilization. There were three important factors making Italy the birthplace of the Renaissance.

-

Italy's geographic location. Renaissance Italy was drawing upon the civilizations of ancient Greece and especially Rome, upon whose ruins it was literally sitting. During the Middle Ages, Italians had neglected and abused their Roman heritage, even stripping marble and stone from Roman buildings for their own constructions. However, by the late Middle Ages, they were becoming more aware of the Roman civilization surrounding them. Italy was also geographically well placed for contact with the Byzantines and Arabs who had preserved classical culture. Both of these factors combined to make Italy well suited to absorb the Greek and Roman heritage.

-

The recent invention of the printing press spread new ideas quickly and accurately. This was especially important now since many Renaissance ideas were not acceptable to the Church. However, with the printing press, these ideas were very hard to suppress.

-

Renaissance Italy, like the ancient Greeks, thrived in the urban culture and vibrant economy of the city-state. This helped in two ways. First, the smaller and more intimate environment of the city-state, combined with the freedom of expression found there, allowed a number of geniuses to flourish and feed off one another's creative energies. Unfortunately, the city-state could also be turbulent and violent, as seen in the riot scene that opens Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. Secondly, the Italian city-states, especially trading and banking centers such as Venice and Florence, provided the money to patronize the arts. Therefore, the wealth and freedom of expression thriving in the urban culture of Italy both helped give birth to the Renaissance.

Renaissance

literally means rebirth, in this case the rebirth of classical Greek and Roman culture. The traditional view of the Renaissance was that it suddenly emerged as a result of the fall of Constantinople in 1453, which drove Greek scholars to seek refuge in Italy and pass classical culture to Italy. Historians now take this as too simplistic an explanation. For one thing, knowledge of Greek and Roman culture had never completely died out in medieval Europe, being kept alive during the Dark Ages in the monasteries, and during the High Middle Ages in the growing universities. Secondly, a revived interest in classical culture can be traced back to the Italian authors, Dante and Petrarch, in the early 1300's. Thus the Italian Renaissance was more the product of a long evolution rather than a sudden outburst.Still, the term "renaissance" has some validity, since its conscious focus was classical culture. The art and architecture drew heavily upon Greek and Roman forms. Historical and political writers used Greek and Roman examples to make their points. And renaissance science, in particular, relied almost slavishly upon Greek and Roman authorities, which was important, since it set up rival authorities to the Church and allowed Western Civilization to break free from the constraints of medieval thought and give birth to the Scientific Revolution during the Enlightenment.

New patterns of thought

Whether one sees the Renaissance as a period of originality or just drawing upon older cultures, it did generate four ideas that have been and still are central to Western Civilization: secularism, humanism, individualism, and skepticism.

-

Secularism comes from the word secular, meaning of this world. Medieval civilization had been largely concerned with religion and the next world. The new economic and political horizons and opportunities that were opening up for Western Europe in the High and Late Middle Ages got people more interested in this world. During the Renaissance people saw this life as worth living for its own sake, not just as preparation for the next world. The art in particular exhibited this secular spirit, showing detailed and accurate scenery, anatomy, and nature, whereas medieval artists generally ignored such things since their paintings were for the glory of God. This is not to say that Renaissance people had lost faith in God. Religion was still the most popular theme for paintings. But during the Renaissance people found other things worth living for besides the afterlife.

-

Humanism goes along with secularism in that it makes human beings, not God, the center of attention. The quotation at the top of this reading certainly emphasizes this point. So did Renaissance art, which portrayed the human body as a thing of beauty in its own right, not like some medieval "comic strip" character whose only reason to exist was for the glory of God. Along those lines, Renaissance philosophers saw humans as intelligent creatures capable of reason (and questioning authority) rather than being mindless pawns helplessly manipulated by God. Even the term for Renaissance philosophers, "humanists", shows how the focus of peoples' attention had shifted from Heaven and God to this world and human beings. It also described the group of scholars who drew upon the more secular Greek and Roman civilizations for inspiration.

-

Individualism takes humanism a step further by saying that individual humans were capable of great accomplishments. The more communal, group oriented society and mentality of the Middle Ages was giving way to a belief in the individual and his achievements. The importance of this was that it freed remarkable individuals and geniuses, such as Leonardo da Vinci to live up to their potential without being held back by a medieval society that discouraged innovation.

Besides the outstanding achievements of Leonardo, one sees individualism expressed in a wide variety of ways during the Renaissance. Artists started signing their paintings, thus showing individualistic pride in their work. Also, the more communal guild system was being replaced by the more individualistic system of capitalism, which encouraged private enterprise.

-

Skepticism, which promoted curiosity and the questioning of authority, was largely an outgrowth of the other three Renaissance ideas. The secular spirit of the age naturally put Renaissance humanists at odds with the Church and its purely religious values and explanations of the universe. Humanism and individualism, with their belief in the ability of human reason, raised challenges to the Church's authority and theories, which in turn led to such things as the Protestant Reformation, the Age of Exploration and the Scientific Revolution, all of which would radically alter how Western Europe views the world and universe. These four new ideas of secularism, humanism, individualism, and skepticism led to innovations in a variety of fields during the Renaissance, the most prominent being literature and learning, art, science, the Age of Exploration, and the Protestant Reformation.

Literature and learning

throughout the Middle Ages were centered on the Church. Consequently, most books were of a religious nature. There were Greek and Roman texts stashed away in the monasteries, but few people paid much attention to them. All that changed during the Renaissance. For one thing, increased wealth and the invention of the printing press created a broader public that could afford an education and printed books. Most of these newly educated people were from the noble and middle classes. Therefore, they wanted a more practical and secular education and books to prepare them for the real world of business and politics.In response to this, new schools were set up to give the sons of nobles and wealthy merchants an education with a broader and more secular curriculum than the Church provided: philosophy, literature, mathematics, history, and politics. Naturally much of the basis for this new curriculum was Greek and Roman culture. Classical authors such as Demosthenes and Cicero were used to teach students how to think, write, and speak clearly. Greek and Roman history were used to teach object lessons in politics. This curriculum provided the skills and knowledge seen as essential for an educated man back then, and served as the basis for school curriculums well into the twentieth century. Only in recent decades has a more technical education largely replaced the curriculum established for us in the Renaissance.

Along the same lines, a more secular literature largely replaced the predominantly religious literature of the Middle Ages. History, as a study of the past (Greek and Roman past in particular) in order to learn lessons for the future, was emerging. So was another emerging new discipline deeply rooted in history: political science. The father of this discipline was Nicolo Machiavelli (1469-1527). His treatise on governing techniques, The Prince, urges the prince to carry on with whatever ruthless means were at his disposal. This serves as a stark contrast to St. Augustine's concept of the "just war."

Another book of a secular nature was Castiglione's The Courtier, which spelled out the ideal education and qualities of a nobleman attending a prince's court. Unlike the usually illiterate and rough mannered medieval noble, Castiglione's courtier should be versed in manners (such as not cleaning one's teeth in public with one's finger). This ideal of the well-rounded "Renaissance Man" hearkens back to the Greek ideal of a well-rounded man and has continued to this day.

Art

is the one field most people associate with the Renaissance since it saw the most radical innovations and breaks with the Middle Ages. Medieval art was religious in tone and for the glory of God. As a result, artists neglected mundane details, thus making the art flat and lifeless. Faces and bodies were cartoon like, having no individual features or anything approaching anatomical detail. Other details such as background, perspective, proportion, and individuality were all virtually unknown.Renaissance art contrasted sharply with medieval art in all these respects. More paintings were on secular themes, especially portraits. And even the religious paintings paid a great deal of attention to glorifying the human form and accomplishments. Starting with Giotto in the early 1300's, Renaissance artists increasingly perfected and used such things as background, perspective, proportion, and individuality. In fact, Leonardo's detail was so good that botanists today can identify the kinds of plants he put into his paintings.

Although painting was especially prominent during the Renaissance, other art forms also flourished. For example, architecture broke somewhat with the medieval Gothic style during the Renaissance. However, it was less innovative and relied more heavily on classical forms, in particular columns, arches, and domes as well as building on a massive scale. Possibly the supreme example of this is the dome of St. Peter's in Rome which was designed by Michelangelo and towers 435 feet from the floor. Music in the Renaissance saw developments that would later blossom into classical music. Instruments were improved and the whole family of violins was developed. Counterpoint (the blending of two melodies) and polyphony (interweaving several melodic lines) also emerged during this period.

Science

saw little advancement, but it was also important for future developments. In particular, classical authorities were discovered who contradicted Aristotle, whose works were accepted by the Church almost as gospel. Finding conflicting authorities forced Renaissance humanists to ask questions that would lead to developing new theories, which in turn would lead to the birth of modern science in the 1600's and 1700's.The Age of Exploration

also showed Renaissance ideas at work. It was secular in its interest in the world. It certainly displayed skepticism by challenging accepted ideas about the world. And the fact that it pitted individual captains against the forces of nature shows it was both humanistic and individualistic.The Protestant Reformation

was one other result of the Italian Renaissance. The spirit of skepticism challenged the authority of the Church, thus opening the way for much more serious challenge later posed by the Protestants. The Protestant Reformation, in turn, would pave the way for new patterns of thought in social, political, economic, and scientific matters.The Italian Renaissance is generally seen as lasting until about 1500, when Italy's political disunity attracted a devastating round of wars and invasions that ended its most innovative cultural period. However, in the process, the invaders took the ideas of the Italian Renaissance back to Northern Europe and sparked what is known as the Northern Renaissance.

FC77An overview of Western Art (c.1400-1950)

Introduction.

The Renaissance (c.1400-1600)

The Baroque

The Rococo (1700s)

However, by latter half of the 1700s, many people were reacting against the cold rationality of the Enlightenment and the frivolous values of the nobles. A new spirit crept into the art, stressing romance over base sensuality and sentimentality over cold reason. Typical of the latter were the paintings by Jean-Baptiste Greuze, showing dreamy looking young women holding fluffy lambs or weeping over their dead pet birds. In reaction to the corrupt values of the old regime there was also more stress given to civic virtue and patriotism, setting the stage for the French Revolution.

Romanticism, Neo-classicism, and Realism (early 1800s)

By contrast, the other school of art, Neo-classicism, created precisely painted images from Greek and Roman myth and history to portray the selfless sacrifices of past heroes in order to inspire present day patriots. Jacques Louis David was especially prominent, doing paintings of such events as the Oath of the Horatii from Roman legend and Leonidas at Thermopylae Pass from Greek history. However, as an apologist for the French Revolution and then for Napoleon, he adapted his style to contemporary events such as the Tennis Court Oath and the death of Marat during the Revolution.

As the century progressed, the two styles each contributed to a third school of art: Realism. Painters such as Gustave Courbet combined the realistic techniques of Neo-classicism with the contemporary themes portrayed by the Romantics. Thus Courbet did paintings of such mundane things as a peasant funeral and a dead trout, topics that critics considered beneath the dignity of portraying on canvas. However, this helped set up the next big movement in painting.

The second great art revolution: Impressionism and Post Impressionism (c.1863-1900)

The Impressionists, such as Monet and Renoir, tried to free themselves from intellectualizing a subject as solid objects such as trees or tables, and then paint each of those objects separately. To this end, they tried to rapidly capture the individual impressions of light in a scene, which together would add up to a picture of that scene, but in a different way from a photograph. Now the emphasis was on the fleeting impressions of light and the emotional impressions they left with the viewer. This technique was especially effective in portraying such things as smoke, rippling water, flags blowing in the breeze, and the splash of colors seen in a bouquet of flowers. Not since the Renaissance had such a revolutionary new approach to art been taken, and the critics and public didn’t like it or accept it for some two decades. But the Impressionists had opened the door to any number of new approaches to painting.

Thus the last decades of the nineteenth century saw a number of new schools of art, sometimes lumped together as the Post Impressionists. On the one hand there was the scientific or geometric approach, epitomized by Paul Cezanne’s attempts to reduce a scene to a collection of basic geometric shapes. Georges Pierre Seurat created whole paintings of tiny colored dots mixed together that would add up to a picture. Paul Gauguin experimented with using solid fields of color rather than shading to create an effect. Another school of art originating in the late 1800s in Germany, Expressionism, focused on portraying emotional experience instead of physical reality. Probably the best known Expressionist painting is Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” (1893).

The early twentieth century (c.1900-1945)

Post Modern art

In recent decades a new term has come into use, postmodern, describing art considered largely contradictory to modern art in its use of such things as collages, objects of consumer or popular culture (e.g., Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup can), words as a central artistic element and various multimedia. . By the late 1970s some critics were even speaking about the “end of painting”, although some artists since the 1980s have returned to representational art, known in its modern incarnation as Figurativism.

FC77AThe Revolution in Renaissance painting

Introduction

Perhaps the most dramatic, or at least widely acclaimed, breakthrough in the Renaissance was in the realm of art, in particular painting. Not only did Renaissance art reflect growing concern with secular subjects, it involved new artistic tools and techniques that more accurately portrayed those subjects. Pre-eminent among those tools was the shift from tempera (egg based) paints painted on wood or as frescoes on walls to oil based paints applied to canvas.

Materials used

Frescoes were wall paintings applied to wet plaster that set into the wall when dry. While this did help preserve the painting, it had several drawbacks. First of all, frescoes dried quickly so an artist had to plan his work thoroughly in advance, since to change any mistakes involved redoing the whole painting. This made frescoes stiff and less spontaneous. Also, the rough surface of a plaster wall made it hard to render details, forcing the artist to use a pointed brush and even at times to stipple the surface dot by dot. To deal with these limitations, an artist would divide the wall into sections, one for each day’s work. He would also do extensive preliminary drawings of the planned painting on the wall.

Tempera was the type of paint used in frescoes, consisting of egg mixed with pigment. This created a light, but somewhat limited range of colors. It dried quickly, which prevented the layering of paints and the subtle shading (known as chiaroscuro) of a painting.

Oil based paints were developed as early as the 1100s and were first widely used in the Low Countries in the early 1400s. Since it dried slowly, oil had three major advantages over tempera. First, it could be layered, which made possible the use of chiaroscuro & sfumato (a technique giving a painting a misty, foggy, or smoky effect). Second, artists could mix colors with oils, giving them a broader and richer palette to work with than ever before. Finally, as evidenced by X-rays of paintings, artists could, and did, change mistakes, thus letting them be more spontaneous in their work.

While oil paints were widely used in the North, they did not reach Italy until about1475. Artists in Venice were the first Italians to use oil enthusiastically, their paintings being distinguished by the rich reds they often used. From Venice, the use of oil based paints spread rapidly across Italy.

Canvas replaced walls as a medium for painting had as dramatic an impact on art as oil replacing tempera. Not having to rely on walls, especially Church walls, for a painting surface, artists could paint smaller portraits and paintings with other themes, opening up wider markets for their talents. Canvas was also more portable, so artists could work in the privacy of their own studios where they could better attract models (especially for nude paintings). These two factors, plus growing middle class patronage, led to a commercial revolution in art and the end of the dominance of the Church, kings, and nobles who previously had the money and walls artists needed. Consequently, they could now pursue a much broader range of topics for paintings than ever before.

New techniques

New techniques in painting also helped transform Renaissance art. The most important of these was linear perspective, which allowed artists to attain three-dimensional effects on a two dimensional surface. Without it, paintings were crowded and limited in the number of people and details that could be represented. Greek and Roman paintings had achieved a high degree of perspective, but their techniques were lost during the Middle Ages. True linear perspective was first attained around 1420 in a remarkable experiment done by Filippo Brunelleschi, the same man who had designed the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence.

Brunelleschi painted Florence’s Baptistery from the perspective of the facing cathedral doorway. He then drilled a hole through the vanishing point of the painting (which faced the Baptistery) and set a mirror in front of it. As someone in the cathedral doorway looked toward the Baptistery through the peephole, Brunelleschi could raise or lower the mirror so the viewer was alternately seeing the Baptistery or the reflection of the painting. Supposedly, his painting and mastery of perspective were so good, viewers could not tell the difference between the real Baptistery and the reflected painting. This dramatic demonstration, plus more secular themes, proper proportion, and attention to details, triggered a virtual revolution, not just in art, but in a whole new way of viewing the world that has become a vital part of our civilization. In the 1600s, this new perspective on the world would help lead to the Scientific Revolution.

FC78The Northern Renaissance (c.1500-1600)

Introduction

There are several reasons why the Renaissance came later to Northern Europe. First, it was further removed from the centers of trade and culture in the Mediterranean. As a result, towns, trade, and the more progressive ideas that tend to come with wealth developed more slowly in the north. Along these lines, the greater influence of feudalism and the Church kept the political, social, and intellectual institutions much more medieval and backward. This in turn provided more resistance to the humanistic ideas developing in Italy.

However, the revival of towns and trade in the North combined with other factors in three ways to bring the Renaissance to Northern Europe. First of all, the urban revival in the North along with the Portuguese and Spanish overseas colonies created the financial resources needed to patronize the arts. Secondly, growing trade in the North, combined with the French invasion of Italy in 1494 and the ability of the printing press to spread ideas quickly and accurately, led to growing contact with the ideas of the Italian Renaissance. Finally, the rise of towns together with the rising national monarchies in France, England, Spain, and Portugal led to the decline of the feudal nobility and medieval Church. This created less resistance to the new ideas from the Renaissance. All these factors came together to produce the Northern Renaissance (c.1500-1600).

The Northern Renaissance should not be seen as a mere copycat of the Italian Renaissance. There were two major differences between the two cultural movements in Italy and the North. First of all, the Church's influence, despite being shaken by recent corruption and scandals, still was strong enough to make the Northern Renaissance more religious in nature. Second, the rising power of the national monarchies made the Northern Renaissance more nationalistic in character.

Reconciling religion and the Renaissance

The more intense religious feelings prevailing in Northern Europe posed a difficult question: could a humanist education based on classical culture be reconciled with Christianity? The answer humanists came up with was yes. This was largely thanks to the greatest humanist of the age: Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466-1536). Called the "Prince of Humanists" and the "scholar of Europe", Erasmus dominated Northern Europe's culture in a way few, if any, other scholars have before or since his time. So great was his reputation that kings and princes from all over Europe competed for his services at their courts. Erasmus popularized classical civilization with his Adages, a collection of ancient proverbs with his own commentaries. His Praise of Folly satirized the follies and vices of the day, in particular those of the Church, while further popularizing humanism. Erasmus was still a pious Christian who pushed the idea that it was one's inner spirit, not outward shows of piety through empty rituals, that really mattered. However, he saw no contradictions between Christianity and ancient cultures. He underscored this attitude by referring to the ancient Greek philosopher, Socrates, as "Saint Socrates".

Other northern humanists picked up this banner. In England, Thomas More brilliantly defended studying classical Greek and Roman culture by saying their knowledge and the study of the natural world could serve as a ladder to the study of the supernatural. Besides, he pointed out, even if theology were the sole aim of one's education, how could one truly know the scriptures without knowing Greek and Hebrew, their original languages? It was in this spirit that the French humanist, Lefebvre d'Etaples, laid five different Hebrew versions of the Book of Psalms side by side in order to get a better translation than the one in the Latin Vulgate Bible. Even in Spain, the most staunchly Christian country in Europe, Cardinal Ximenes, who served as virtual prime minister for Ferdinand and Isabella, set up a university at Alcala with a very humanist curriculum. Its purpose was to use humanism to provide better understanding of Christianity. The major accomplishment of Erasmus and the Northern humanists was that they successfully defended the study of the classics and a more secular education as a ladder to better understanding of Christianity. This in turn paved the way for using a secular education for more secular purposes and that would revolutionize Western Civilization.

Art also reflected the more religious nature of the Northern Renaissance. Secular and even mythological themes would appear, but with less frequency then in Italy. This intense religious passion is especially reflected in the work of the Spanish artist, El Greco. Technically, art in the North lagged behind Italy throughout the 1400's, especially in its use of perspective and proportion. The key turning point came when the German artist, Albrecht Durer, traveled to Italy in 1494 to study its art. Durer was heavily influenced by the Italians and the ancient writer, Vitruvius, in their efforts to find the mathematical proportions for portraying the perfect figure. Among other things, this shows a growing fusion of art and science that anticipated the scientific revolution that would sweep Europe two centuries later. Other northern artists followed Durer, and from this time one sees a more realistic art in the North, which approached the standards of the Italian artists.

The emerging national cultures in the Northern Renaissance

The other major feature of the Northern Renaissance was the national character of the cultures that were evolving along with their respective nation-states in Europe. The literature of the age especially showed this. For one thing, it tended to be written in the vernacular and reflected its respective national cultures. In Spain the great literary genius was Cervantes, whose Don Quixote showed the changing values of the age by satirizing the medieval values of the nobility. Probably the greatest literary genius of the age was William Shakespeare, whose work reflects heavy influence from the Italian Renaissance. Many of his plays have Greek and Roman themes, sometimes copying the plot lines from classical plays (e.g.-- Comedy of Errors) or take place in Italy (e.g.-- Romeo and Juliet). However, many of Shakespeare's other plays take place in England and reflect the fact that the various nations in Northern Europe were defining their own unique cultures apart from Italian and classical influence.

Results of the Northern Renaissance

Ironically, one could say the most important result of the Northern Renaissance was a religious revolution. This was the result of a several factors: anger at the church's corruption, the rising power of kings at the expense of the popes, and the fusion of Renaissance ideas from Italy with the still intense religious fervor and emerging national cultures of the North. The dynamic combination of these factors would lead to the Protestant Reformation that, in turn, would branch off in three lines of development.

First, the Protestant Reformation would open the way for new ideas about money and the middle class, and that would lead to the triumph of capitalism in Northern Europe. Secondly, the Protestant Reformation would play a vital role by shattering the Church's monopoly on religious truth, breaking its iron grip on scientific thinking, and paving the way for the Scientific Revolution of the late 1600's and 1700's.

Third, the growing power of kings in Northern Europe, combined with Renaissance learning and local anger at Church abuses, helped pave the way for more secular theories about the state. The Reformation, by challenging the power of the Church, would also help kings in their claims to greater sovereignty through the theory of Divine Right of Kings. Ironically, the Reformation would also provide the theoretical backing for the democratic revolutions that would eventually overthrow the very monarchies that tried to use it against the Church in the first place.

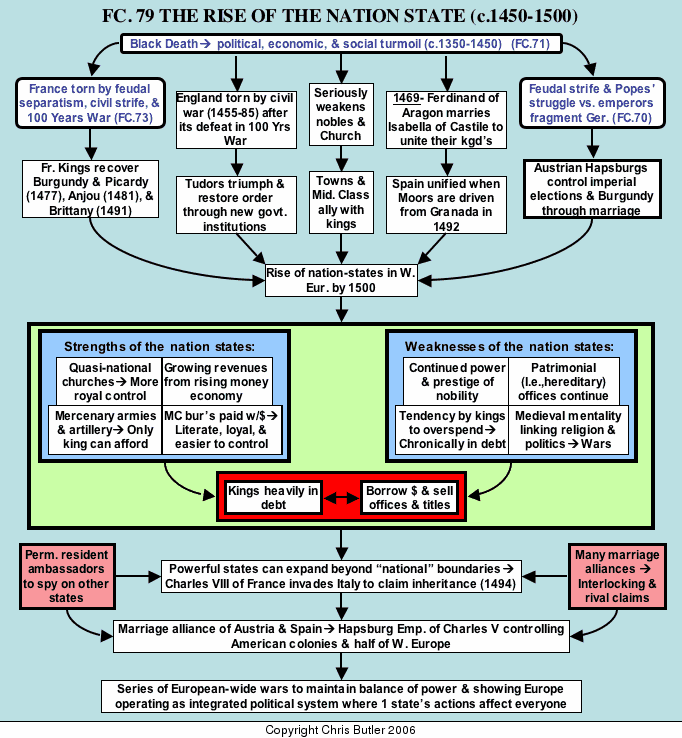

FC79The rise of the nation state during the Renaissance

Just as the turmoil of the Later Middle Ages had cleared the way for sweeping economic, cultural, and technological changes in Western Europe, it likewise produced significant political changes that led to the emergence of a new type of state in Western Europe: the nation state. It did this along five lines of development, four of them corresponding to various nation-states in Europe and the other having to do with the overall decline of the Church and nobles which helped lead to the revival of towns and middle class allied to the kings.

The later 1400's saw kings in Western Europe picking up the pieces left by the turmoil of the last century in order to build stronger states. However, this process of unification, or in some cases reunification, involved more violence and warfare. In England, the aftermath of the Hundred Years War saw a period of civil strife known as the Wars of the Roses (1455-85) over control of the throne. In the end, Henry Tudor, who became Henry VII, triumphed and restored order with such new government institutions as the Star Chamber.

France, badly hurt by the Hundred Years War, gradually reunified as the Valois kings regained control of Picardy (1477), Anjou (1481), and Brittany (1491). The greatest challenge to the French kings came from the powerful and aggressive Charles the Bold of Burgundy. Charles controlled both Burgundy and the Low Countries (Flanders and the Netherlands) and threatened to become a major power in his own right until he met disaster at the hands of the Swiss pikemen at the Battle of Nancy (1477). With this potent threat removed and Burgundy also back under French control, a strong unified French state was emerging by 1500 after some 150 years of conflict.

A unified Spain also was born by 1500. The key event here was the marriage in 1469 of Isabella of Castile to Ferdinand of Aragon, which united most of Spain under their joint rule. (However, the two states continued to function largely as separate administrative entities for generations to come.) The final piece of the puzzle was put into place when the last of the Spanish Muslim states, Granada, was conquered in 1492. Among other things, this freed the new Spanish state to fund the voyage of a Genoese captain named Christopher Columbus who was looking for new routes to the spices of the East.

Even Germany, fragmented after centuries of feudal strife and the emperors' struggle with the Papacy, saw its fortunes seem to revive with the rise of the Hapsburg Dynasty that controlled the imperial throne at this time. This family, through a number of astute marriage alliances, would come to control Austria, the Low Countries, Hungary, and Spain along with its Italian possessions and American colonies. In fact, as impressive as this empire looked, it worked to Germany's disadvantage since it would trigger a number of wars to crush the Hapsburg "superpower"-- wars that would use Germany as a battleground and ruin it. Therefore, by 1500, nation states were evolving, having their own strengths and problems.

Strengths of the new nation-states consisted of four main pillars of support: money, which in turn enabled kings to pay for professional bureaucracies and mercenary armies, and control of the Church. This mixture of medieval and modern elements underscores the transition of Europe from the medieval to modern era.

Finances

The old medieval sources of revenue, such as feudal dues and income from royal lands and monopolies, were totally inadequate for the greater burdens, which the new types of government and army placed on Renaissance kings. Borrowing money against future tax revenues was a dead end that just got kings into deeper trouble, although that was commonly the practice. However, more regular taxes had to be collected. In France, the "extraordinary" taxes the townsmen had granted the crown to drive out the English in the Hundred Years War were collected annually and became a permanent tax, the taille. In Spain, the crown increased sales taxes to boost revenues. In England, the king was unable to get a high permanent tax granted to him by Parliament. He did increase his control over revenues for such things as customs on wool and cloth. Luckily, England was an island and in less need of a large expensive army and bureaucracy than states on the continent. Overall, Renaissance kings by 1500 were still faced with serious financial shortcomings. However, no one else in their realms possessed the resources to effectively challenge them. Along with their bureaucracies and armies, their finances presented a picture of the European state in transition from the medieval to the modern era.

Bureaucracies

consisted mainly of members of the middle class with the education and experience needed to run the government. Since kings were usually desperate for money, they resorted to selling government offices, a practice known as venality of office. This system had its good and bad points. The main good points were that it provided the king with some much needed cash and officials who showed more efficiency and loyalty to their king than the old feudal nobility had.The main drawback was that such a system bred corruption, since money, not ability, was often the key to gaining office. Bureaucrats tended to assume their own consciousness as a class, maintaining a common silence to thwart any attempts to weed out corruption. They could often successfully resist or slow down reforms or other policies they did not like. But, for all the problems the new bureaucracy created, it was still more efficient than the old feudal system and gave kings a far greater degree of control over their states.

The new warfare

Renaissance armies told a similar story, being somewhat unruly but still better than their feudal predecessors. The ranks were now filled with mercenaries who fought until the king's money ran out. This gave the king much longer campaigning seasons than the forty days that feudal vassals typically owed. But it could still present some serious, and, at times, embarrassing problems. As soon as the king ran out of money, such armies would often desert or refuse to fight any longer. Also, since they were not usually natives of the state they were fighting for, they often had no qualms about plundering the people they were supposedly defending. Despite these drawbacks, Renaissance armies gave kings in Western Europe much tighter control over their states, largely because they were so expensive that no one but kings could afford to maintain them.

Part of that expense lay in the new type of warfare emerging by 1500. Although heavily armored knights were still prominent, their role was being reduced by two new ways of fighting, one medieval and one modern. One was massed formations of pikemen, reminiscent of the old Greek and Macedonian phalanxes, who formed the core of the Renaissance army. Until the early 1500's, the Swiss were reputedly Europe's best pikemen, and every prince wanted Swiss mercenaries in his army, no matter what the cost. In the 1500's, German pikemen, known as landsknechte, and Spanish pikemen would rival the Swiss in their reputations for ferocity on the battlefield.

The other new and expensive element emerging in the new warfare was gunpowder. Hanging on the flanks of each pike square were men wielding primitive muskets. Such guns were heavy, hard to load, and even harder to aim accurately. They also presented the danger of blowing up in their users' faces. Still, they could be very deadly when fired in massed volleys, having a range of up to 100 meters. Gradual but constant improvements, such as the matchlock that freed both hands for aiming, made them increasingly effective throughout the 1400's and 1500's. As a result, the number of musketeers, and their cost, gradually climbed throughout this period. The combination of guns' firepower with the solid pike formations proved to be the most potent military innovation of the Renaissance. It ruled Europe's battlefields until the later 1600's when better muskets and the bayonet phased out the pikeman for good.

Artillery was another important, but expensive, element in the Renaissance prince's army. Smaller and more mobile cannons were made for use in pitched battles as well as sieges. There was no standardization in the Renaissance artillery corps, each cannon being made by an independent contractor. The French, with Europe's best artillery, had 17 separate gauges of artillery requiring 17 different sizes of shot. The Hapsburg emperor, Charles V, had 50 different gauges. Obviously, this could create untold confusion in the heat of battle.

The advent of artillery made the tall thin walls of medieval castles obsolete, since they were so easily breached by cannons' firepower. However, this did not make fortifications obsolete. By the early 1500's, a new style of fortifications, the trace Italienne, was coming into use and slowing down, if not stopping artillery. These new fortifications were much thicker and more elaborate than their medieval predecessors, having multiple sets of walls, moats, and bastions set at different angles to one another to provide flanking fire from various directions against any enemy assaults. As with muskets and artillery, these new forts were so expensive that only kings could afford them or, more properly, afford to go into debt to bankers to buy them. And, by the same token, this increased the kings' power and put any rebellious nobles more at the kings' mercy.

This new type of warfare and army showed the beginnings of some aspects we associate with modern warfare. For one thing, it was expensive because of the size of its armies and the new technology. It was also very destructive to the inhabitants who were unlucky enough to be in the path of these plundering mercenaries and their hordes of camp followers. The seventeenth century general, Albrecht von Wallenstein, once said he could better support an army of 50,00 than one of 20,000 since it could more effectively plunder the countryside. This says a lot about supplying such armies and its effect on military strategy: fight in the enemy's territory and make him pay for the war. Finally, the new warfare was much bloodier than the medieval warfare that preceded it. We find nobles complaining because any low born peasant with a small amount of training and a gun could blow them out of the saddle. Even more significantly, the humanists condemned warfare for its bloodiness, no matter to what class. Throughout the modern era, that outcry has slowly gained force with the growing destructiveness of warfare.

The Church

was still the largest single landholder in Western Europe, making it mandatory for kings to control this vital source of revenue and propaganda. Luckily for the kings, the Church's power and prestige were seriously weakened by the popular discontent and corruption that climaxed with the Great Schism. In France, kings had gained the loyalty of the local clergy against the Italian higher clergy appointed by the popes and won their struggle to rule the French clergy in the Pragmatic Sanction of Bourges in 1438. This recognized the king's claim to the Gallican Liberties, transferring the direct loyalty of the French clergy from the pope to their king.Elsewhere, the story was similar. In England, during the Avignon Papacy of the 1300's, kings had limited the right of foreign clergy to visit England and also restricted English clergy in their right to appeal to foreign (i.e., papal) courts. In Spain, the crown came to dominate the Church and, with it, the Inquisition. In all these countries, levying Church taxes was subject to the approval of the kings, who often made a deal to get a percentage of the taxes for themselves.

In addition to the structure of the emerging nation-state, peoples' attitudes toward that state were also in transition from a very personal feudal outlook to a broader concept of a nation. There was a growing awareness among various peoples that there were factors, such as language and culture, making them unique as nations. But the form of nationalism we are familiar with was still several centuries away. During this transitional period, the loyalties of people focused largely on the person of a king rather than on the nation's people as a whole.

Limits to the Renaissance state's power

We should keep in mind that, while the Renaissance state was a vast improvement over the feudal anarchy of the Middle Ages, it was still rudimentary and highly inefficient when compared to the modern state. There were three main limitations to state building at this time.

First of all, the decentralized chaos of the Dark Ages had given rise to a multitude of local institutions and customs, rights, and inherited titles and offices. France alone had some 300 local legal systems dating back to a time when there was essentially no central government, while there were 700 in the Netherlands. The force of tradition with centuries of history to back it up made it well nigh impossible for kings to do away with these offices, customs, and privileges. A good example of this were the parlements, local French courts which could modify the king's laws, delay enforcing them, or even refuse to enforce them if they thought those laws interfered with long established local customs and traditions. As a result, kings were forced either to work around the old offices by creating new parallel offices that would very gradually take over their functions, or incorporate the old offices into the new state apparatus. What this meant was that any regularization of government institutions and practices on a national scale was still centuries away.

A second problem was the continued existence and aspirations of the nobles. While we have seen them suffering from a prolonged decline since the High Middle Ages, they remained somewhat resilient as a class. One big reason for this was that they were still seen as the class to belong to, and many middle class merchants and bankers were eager to buy noble titles and lands so they could carry on like the nobles of old. A prime example of this was the Fuggers of Augsburg, Germany, the richest banking family in Europe, who bought noble titles and lands and passed into idle noble obscurity. Aiding this process were the kings who were always in need of cash and willing to sell noble titles and offices to anyone with the money. As a result, fresh blood kept infusing the nobility with new life. Unfortunately, these nobles, of whatever origin, could still be quite troublesome and lead revolts against their rulers, as happened in the Netherlands (1566), England (1569), and France (1582).

A third problem was the kings' inability or unwillingness to stay out of debt and pay their armies and bureaucrats. This encouraged corruption in the government and plundering and desertion by the mercenaries, which further reduced the kings' revenues and ability to pay their bills, leading to more loans at high rates of interest, and so on. Finally, although kings could control their national churches, they could not control the medieval mentality still linking politics and religion and causing disastrous wars over religious issues. This especially became a problem after 1560 in the repeated religious wars between Protestants and Catholics.

The "New Diplomacy"

Despite these problems, a new and more dynamic type of nation state was emerging by 1500. And once kings had affairs within their own borders reasonably under control, they started extending their involvement in diplomacy outside of their states. By 1500, we see Western Europe starting to function as an integrated political system, whereby one state's acts affected all the other states and triggered appropriate reactions. This new interdependence and sensitivity to other states' plans and actions sparked the beginnings of modern diplomacy. Two factors aided this process of outward expansion, and, once again, they were a mixture of medieval and modern forces.

Among the older methods still used to consolidate and improve a prince's position, the most notable was the marriage alliance. Rulers still thought of their states as their property. That property could be passed on to their sons, and it could be added to by marrying into another ruling family and assuming all or part of that family's property (i.e., state) as part of the deal. A number of such marriages took place in this period. Henry VII of England married Elizabeth of York, the heiress of his chief rival to the throne, a union that gave him undisputed claim to the crown. Charles VIII of France married Anne of Brittany and tied that region much more closely to the French king's interests.

Certainly the most spectacular example of dynastic empire building through marriage was the Hapsburg Empire, which controlled most of Western Europe in the first half of the 1500's. In 1469, Ferdinand of Aragon married Isabella of Castile, thus uniting Spain under one house, although the two governments functioned separately for some time. Meanwhile, the Hapsburg emperor, Maximillian, had wed Mary, duchess of Burgundy, and added Burgundy and the Low Countries (Flanders and Holland) to his family lands in Austria and the Holy Roman Empire. Finally, their son, Philip, married Ferdinand and Isabella's daughter, Joanna, to seal an alliance in reaction against the French invasion of Italy in 1494. The product of that union, Charles V (Charles I of Spain), inherited most of Western Europe: Germany, Austria, the Low Countries, most of Italy, and Spain with its American holdings. As the contemporary saying put it: "Others make war, but you, happy Austria, make marriages."

Marriage alliances alone were not enough to keep one diplomatically safe. For one thing, they created nearly as many problems as they solved. Since the network of marriage alliances was so extensive and interlocking there were almost always numerous claimants for vacant thrones whenever a ruler died childless. Such a situation often triggered wars, despite the original intention of the marriage alliance to stop such wars. Second, the Renaissance, with its increased political interdependence between states, created shifting alliances to maintain or improve their positions. This required a ruler to keep a much closer eye on what other states were doing so that they could not surprise him by switching alliances or suddenly declaring war. This led to permanent resident ambassadors, forerunners or our own modern diplomats.

Like so many other innovations, the idea of keeping permanent ambassadors at other rulers' courts originated in Italy. Previously, negotiations between states involved sending special ambassadors only for special occasions, such as a treaty of alliance or celebrating a dynastic marriage. By 1450, a delicate balance of power had evolved in Italy between its five main states: Milan, Venice, Florence, the Papal States, and Naples. The weakest of these states, Florence, felt nervous about its more powerful neighbors and wanted to maintain the balance of power to keep any one of them from threatening its own security. Therefore, it started maintaining permanent resident ambassadors at the other states' courts.

During the Renaissance, these officials were mainly of lower noble and middle class origin. They were expected to maintain themselves in the high style of their home court while being engaged in information gathering, which amounted to little more than spying. They had to send weekly letters home, often in code, repeating all pertinent facts, rumors, conversations, and character descriptions they could come up with. All this was done at their own expense, which many of them could not afford. We have letters from such men, pleading with their home governments not to force them to serve. Usually such pleas were to no avail.

There was no diplomatic immunity then, and the resident ambassadors suffered accordingly. Foreign courts saw them as spies and treated them as such, subjecting them to hostile treatment, insults, surveillance, imprisonment, and even torture. To add insult to injury, the home government often did not believe the letters these men sent home and kept spies at the court to watch their own diplomats. When important negotiations were to take place, the home government still appointed special ambassadors of high noble status to do the job.

In 1494, the French king Charles VIII invaded Italy. This prompted the intervention and fateful marriage alliance of Spain and the Holy Roman emperor, Maximillian, mentioned above. It also touched off a series of wars that devastated Italy and ended its leadership in European affairs. All these wars and shifting alliances caused the great rulers of Europe to start maintaining permanent ambassadors at each other’s courts. Over the years, as resident ambassadors became a permanent fixture of diplomacy in Europe and the world, their status and treatment would improve. Florence's policy of maintaining a stable balance of power would also spread northward and become a cornerstone of European diplomacy in the centuries to come.