Reformation & religious warsUnit 13: The Age of Reformation and religious wars (1517-1648)

FC84The roots and birth of the Protestant Reformation

The roots of the Reformation lie far back in the High Middle Ages with the rise of towns and a money economy. This led to four lines of development that all converged in the Reformation. First of all, a money economy led to the rise of kings who clashed with the popes over control of Church taxes. One of these clashes, that between pope Boniface VIII and Philip IV of France, triggered the Babylonian Captivity and the Great Schism. Second, the replacement of a land based with a money economy led to growing numbers of abuses by the Church in its desperation for cash. Both of these factors seriously damaged the Church’s reputation and helped lead to the Lollard and Hussite heresies which would heavily influence Luther’s Protestant Reformation.

Another effect of the rise of towns was a more plentiful supply of money with which humanists could patronize Renaissance culture. When the Renaissance reached Northern Europe, the idea of studying the Bible in the original Greek and Hebrew fused with the North’s greater emphasis on religion, thus paving the way for a Biblical scholar such as Martin Luther to challenge the Church.

Finally, towns and trade spread new ideas and technology. Several of these bits of technology, some from as far away as China, helped lead to the invention of the printing press which helped the Reformation in two ways. First of all, it made books cheaper, which let Luther have his own copy of the Bible and the chance to find what he saw as flaws in the Church’s thinking. Second, the printing press would spread Luther’s ideas much more quickly and further a field than the Lollards and Hussites ever could have without the printing press.

All of these factors, growing dissatisfaction with corruption and scandal in the Church, the religious emphasis of the Northern Renaissance, and the printing press, combined to create a growing interest in Biblical scholarship. Nowhere was this interest more volatile or dangerous than in Germany. The main reason for this was the fragmentation of Germany into over 300 states, which helped the Reformation in two ways.

For one thing, there was no one power to stop the large number of Church abuses afflicting Germany, thus breeding a great deal of anger in Germany against the Church. For another thing, the lack of central control also made it very difficult to stop the spread of any new ideas. This was especially true in Germany, with over 30 printing presses, few, if any, being under tight centralized control, and each of which was capable of quickly churning out literally thousands of copies of Protestant books and pamphlets. If Germany could be seen as a tinder box just waiting for a spark to set it aflame, Martin Luther was that spark.

Luther, like all great men who shape history, was also a product of his own age. He had a strict religious upbringing, especially from his father who frequently beat his son for the slightest mistakes. School was little better. Young Martin was supposedly beaten fifteen times in one day for misdeclining a noun. All this created a tremendous sense of guilt and sinfulness in him and influenced his view of God as a harsh and terrifying being. Therefore, Luther’s reaction to the above mentioned thunderstorm in 1506 should come as no surprise. He carried out his vow and joined a monastic order.

As a monk, Luther carried his religious sense of guilt to self-destructive extremes, describing how he almost tortured himself to death through praying, reading, and vigils. Indeed, one morning, his fellow monks came into his cell to find him lying senseless on the ground. Given this situation, something had to give: either Luther’s body or his concept of Christianity. His body survived.

Out of concern for Martin, his fellow monks, thanks to the printing press, gave him a copy of the Bible where Luther found two passages that would change his life and history: “ For by grace are you saved through faith; and that not of yourselves: it is the gift of God; not of works, lest any man should boast.” (Ephesians 2:8-9) “ Therefore, we conclude that a man is justified by faith without the deeds of the law.” (Romans 3:28) As Luther put it, “ Thereupon I felt as if I had been born again and had entered paradise through wide open gates. Immediately the whole of Scripture took on a new meaning for me. I raced through the Scriptures, so far as my memory went, and found analogies in other expressions.” From this Luther concluded that faith is a “free gift of God” and that no amount of praying, good deeds or self-abuse could affect one’s salvation. Only faith could do that.

The storm breaks

In the following years, Luther’s ideas quietly matured as he pursued a career as a professor, back then a Church position. Then, in 1517, trouble erupted. Pope Leo X, desperate for money to complete the magnificent St. Peter’s cathedral in Rome, authorized the sale of indulgences. These were documents issued by the Church that supposedly relieved their owners of time in purgatory, a place where Catholics believe they must purge themselves of their sins before going to heaven. Originally, indulgences had been granted to crusaders for their efforts for the faith. In time they were sold to any of the faithful who wanted them. The idea was that the money paid was the result of one’s hard work and was sanctified by being donated to the Church. However, it was easily subject to abuse as a convenient way to raise money.

Indulgence sales were especially profitable in Germany where there was no strong central government to stop the Church from taking money out of the country. This greatly angered many Germans and made them more ready to listen to criticism of the Church when it came. The Church’s agent for selling indulgences in Brandenburg in Northern Germany, John Tetzel, used some highly questionable methods. He reportedly told local peasants that these indulgences would relive them of the guilt for sins they wished to commit in the future and that, after buying them, the surrounding hills would turn to silver. He even had a little jingle, much like a commercial: “ As soon as coin in coffer rings a soul from Purgatory springs.”

Luther was then a professor in nearby Wittenburg, Saxony, not far from the home of the Hussite heresy in Bohemia. When some local people showed him the indulgences they had bought, he denied they were valid. Tetzel denounced Luther for this, and Luther took up the challenge. On October 31, 1517, Luther nailed a placard to the church door in Wittenburg. On it were the Ninety-five Theses, or statements criticizing various Church practices, some of which are given here.

26. “They preach mad, who say that the soul flies out of purgatory as soon as the money thrown into the chest rattles.

27. “It is certain that, when the money rattles in the chest, avarice and gain may be

increased, but the suffrage of the Church depends on the will of God alone…32. “Those who believe that, through letters of pardon, they are made sure of their own salvation, will be eternally damned along with their teachers.

43.“Christians should be taught that he who gives to a poor man, or lends to a needy man,

does better than if he bought pardons…56. “The treasures of the Church, whence the Pope grants indulgences, are neither sufficiently named nor known among the people of Christ.

65 & 66. “Hence the treasures of the Gospel are nets, wherewith they now fish for the men of riches...The treasures of indulgences are nets, wherewith they now fish for the riches of men…

86. “Again; why does not the Pope, whose riches are at this day more ample than those of the wealthiest of the wealthy, build the one Basilica of St. Peter when his own money, rather than with that of poor believers…?

Luther’s purpose was not to break away from the Church, but merely to stimulate debate, a time honored academic tradition. The result, however, was a full-scale religious reformation that would destroy Europe’s religious unity forever.

Soon copies of Luther’s Ninety-five Theses were printed and spread all over Germany where they found a receptive audience. Indulgence sales plummeted and the authorities in Rome were soon concerned about this obscure professor from Wittenburg. Papal legates were sent to talk sense into Luther. At first, he was open to reconciliation with the Church, but, more and more, he found himself defying the Church. Luther’s own rhetoric against the Church was becoming much more radical:

“If Rome thus believes and teaches with the knowledge of popes and cardinals (which I hope is not the case), then in these writings I freely declare that the true Antichrist is sitting in the temple of God and is reigning in Rome—that empurpled Babylon—and that the Roman Church is the Synagogue of Satan…If we strike thieves with the gallows, robbers with the sword, heretics with fire, why do we not much more attack in arms these masters of perdition, these cardinals, these popes, and all this sink of the Roman Sodom which has without end corrupted the Church of God, and wash our hands in their blood?”

“…Oh that God from heaven would soon destroy thy throne and sink it in the abyss of Hell!….Oh Christ my Lord, look down, let the day of they judgment break, and destroy the devil’s nest at Rome.”

Luther also realized how to exploit the issue of the Italian church draining money from Germany:

“Some have estimated that every year more than 300,000 gulden find their way from Germany to Italy…We here come to the heart of the matter…How comes it that we Germans must put up with such robbery and such extortion of our property at the hands of the pope?….If we justly hand thieves and behead robbers, why should we let Roman avarice go free? For he is the greatest thief and robber that has come or can come into the world, and all in the holy name of Christ and St. Peter. Who can longer endure it or keep silence?”

The papal envoy, Aleander, described the anti-Catholic climate in Germany:

“…All German is up in arms against Rome. All the world is clamoring for a council that shall meet on German soil. Papal bulls of excommunication are laughed at. Numbers of people have ceased to receive the sacrament of penance… Martin (Luther) is pictured with a halo above his head. The people kiss these pictures. Such a quantity has been sold that I am unable to obtain one… I cannot go out in the streets but the Germans put their hands to their swords and gnash their teeth at me…”

What had started as a simple debate over Church practices was quickly becoming an open challenge to papal authority. The Hapsburg emperor, Charles V, needing Church support to rule his empire, feared this religious turmoil would spill over into political turmoil. Therefore, although religiously tolerant by the day’s standards, Charles felt he had to deal with this upstart monk. A council of German princes, the Diet of Worms, was called in 1521. At this council, the German princes, opposed to the growth of imperial power at their expense, applauded Luther and his efforts. As a result, Charles had to summon Luther to the diet so he could defend himself.

Luther’s friends, remembering Jan Hus’ fate, feared treachery and urged him not to go. But Luther was determined to go “ though there were as many devils in Wurms as there are tiles on the roofs.” His trip to Worms was like a triumphal parade, as crowds of people came out to see him. Then came the climactic meeting between the emperor and the obscure monk. Luther walked into an assembly packed to the rafters with people sensing history in the making. A papal envoy stood next to a table loaded with Luther’s writings. Asked if he would take back what he had said and written, Luther replied:

“Unless I am convinced by the evidence of Scripture or by plain reason—for I do not accept the authority of the Pope, or the councils alone, since it is established that they have often erred and contradicted themselves—I am bound by the scriptures I have cited and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything, for it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. God help me. Amen.”

Having defied Church and empire, Luther was hurried out of town where he was “ambushed” by his protector, Frederick of Saxony, and hidden in Wartburg castle to keep him out of harm’s way. However, although Luther dropped out of sight for a year, the Reformation did not go away.

Luther’s religion

Because of his criticism of papal authority and Church practices, Luther had been excommunicated from the Church. This along with the dramatic meeting at Worms led him to make a final break with the Catholic Church and form Lutheranism, the first of the Protestant faiths. This was not a new religion. It had basically the same beliefs about God as the Catholic faith. However, there were four main beliefs in the Lutheran faith that differed substantially from Catholicism.

-

Faith alone can gain salvation. No amount of good works can make any difference because man is so lowly compared to God. In the Catholic faith, penance and good works are important to salvation.

-

Religious truth and authority lie only in the word of God revealed in the Bible, not in any visible institutions of the Church. This largely reflects what Wycliffe had said about the many institutions and rituals the Church valued. As a result, Lutheranism tended to be simpler in practice than Catholicism.

-

The church is the community of all believers, and there is no real difference between priest and layman in the eyes of God. The Catholic Church gave greater status to the clergy who devoted their lives to God.

-

The essence of Christian living lies in serving God in one’s own calling. In other words, all useful occupations, not just the priesthood, are valuable in God’s eyes. This especially appealed to the rising middle class whose concern for money was seen as somewhat unethical by the Medieval Church.

The spread of Lutheranism

When the Church burned 300 copies of Hus’ and Wycliffe’s writings in the early 1400’s, this dealt a heavy blow to the Hussite movement. However, from the start of the Reformation, printed copies of Luther’s writings were spread far and wide in such numbers that the movement could not be contained. By 1524, there were 990 different books in print in Germany. Eighty percent of those were by Luther and his followers, with some 100,000 copies of his German translation of the Bible in circulation by his death. Comparing that number to the 300 copies of Hussite writings underscores the decisive role of the printing press in the Protestant Reformation.

When discussing whom in society went Lutheran or stayed Catholic and why, various economic and political factors were important, but the single most important factor in one’s decision was religious conviction. This was still an age of faith, and we today must be careful not to downplay that factor. However, other factors did influence various groups in the faith they adopted.

Many German princes saw adopting Lutheranism as an opportunity to increase their own power by confiscating Church lands and wealth. Many middle class businessmen, as stated above, felt the Lutheran faith justified their activities as more worthwhile in the eyes of God. The lower classes at times adopted one faith as a form of protest against the ruling classes. As a result, nobles tended to be suspicious of the spread of a Protestant faith as a form of social and political rebellion. Many Germans also saw Lutheranism as a reaction against the Italian controlled Church that drained so much money from Germany. However, many German people remained Catholic despite any material advantages Lutheranism might bestow. For both Catholics and Protestants, faith was still the primary consideration in the religion they adopted.

Lutheranism did not win over all of Germany, let alone all of Europe. Within Germany, Lutherans were strongest in the north, while the south largely remained Catholic. However, Germany’s central location helped Protestants spread their doctrine from Northern Germany to Scandinavia, England, and the Netherlands.

Luther’s achievement

Although Luther had not originally intended to break with Rome, once it was done he tried to keep religious movement from straying from its true path of righteousness. Therefore he came out of hiding to denounce new more radical preachers. He also made the controversial stand of supporting the German princes against a major peasant revolt in Germany in 1525, since he saw the German princes’ support as vital to the Reformation’s survival. This opened Luther to attacks by more radical Protestants who saw him as too conservative, labeling him the “Witternburg Pope”. However, as the Protestant movement grew and spread, it became increasingly harder for Luther to control.

Martin Luther died February 18, 1546 at the age of 63. By this time events had gotten largely out of his control and were taking violent and radical turns that Luther never would have liked. Ironically, Luther, who had started his career with such a tortured soul and unleashed such disruptive forces on Europe, died quite at peace with God and himself. Like so many great men, he was both a part of his times and ahead of those times, thus serving as a bridge to the future. He went to the grave with many old Medieval Christian beliefs. However, his ideas shattered Christian unity in Western Europe, opening the way for new visions and ideas in such areas as capitalism, democracy, and science that shape our civilization today.

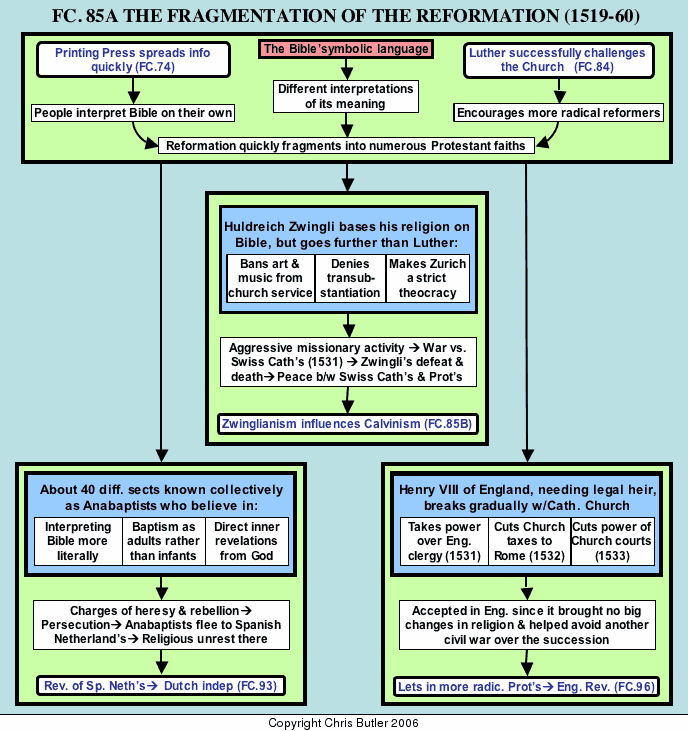

FC85AThe Reformation fragments I: Zwinglianism & Anabaptism

Introduction

While the Catholic Church kept Western Europe religiously united for 1000 years, Protestant unity broke up almost immediately. There were three major reasons for this. First, Luther's successful challenge to the Catholic Church set an example for other reformers to follow. Second, the printing press and translations of the Bible from Latin to the vernacular let more people read and interpret scripture on their own. Previously, the Church's monopoly on Bibles, all written in Latin, severely limited individual interpretations. Finally, the Bible itself is often vague, which also encouraged widely differing interpretations. Consequently, a number of different sects (religious groups) sprang up on the heels of Luther's Reformation.

Huldreich Zwingli and the Swiss Reformation

The first break in Protestant unity came from the Swiss reformer, Huldreich Zwingli. Although only a year younger than Luther, Zwingli seemed to come from a different world. While Luther's outlook and background were very medieval, Zwingli received a liberal humanist education and did not have the great sense of guilt and fear of the terrors of hell his German counterpart had. Zwingli's humanist education influenced him to call for a religion based entirely on the Bible. In 1518 he became a common preacher in Zurich, Switzerland and echoed Luther by speaking out against Bernhardin Samson, a local seller of indulgences. He also denounced other church abuses and thus launched the Swiss Reformation.

Zwingli's religion was both similar to and different from Luther's. Like Luther, he stressed a more personal relationship between man and God, claimed faith alone could save one's soul, and denied the validity of many Catholic beliefs and customs such as purgatory, monasteries, and a celibate (unmarried) clergy. However, Zwingli's goal from the first was to break completely from the Catholic Church. His plan for doing this was to establish a theocracy (church run state) in Zurich.

By 1525, he had accomplished this, having banished the Catholic mass and introduced services in the vernacular. He vastly simplified the service to sermon and scripture readings. Despite his love of music, Zwingli banned it from the service and even smashed the church organ. He either destroyed or whitewashed religious images, which he saw as idolatrous, served communion in a wooden bowl rather than a silver chalice, and closed down monasteries or turned them into hospitals and schools. Although not persecuted, Catholics had to pay fines for attending mass and eating fish on Fridays (a Catholic practice then to symbolize personal sacrifice by not eating meat) and were excluded from public office. Zwingli also closely supervised the morals of his congregation. All these measures anticipated the later reforms of John Calvin.

By 1528, Zwingli's reforms had spread across northern Switzerland with the South remaining Catholic. Because of fear of being caught between Catholics in southern Switzerland and Germany to the north Zwingli followed a more aggressive foreign policy and attempts to unite with the Lutherans in common cause against the Catholics. The proposed alliance never occurred because the two camps could not agree on one piece of theology: whether the bread and wine of communion were actually transubstantiated (transformed) into the body and blood of Christ. The Catholic Church had claimed for centuries that transubstantiation did take place, and Luther agreed with them in a modified form. Zwingli said it was only symbolic of Christ's body and blood. A personal meeting between Luther and Zwingli in 1529 accomplished nothing except hard feelings, and the proposed alliance between the Zwinglians and Lutherans fell through.

Aggressive Zwinglian missionaries in the Catholic districts of Switzerland led to war in 1531, and an army of 8000 Catholics destroyed Zwingli and his force of 1500 men. An uneasy co-existence between Protestants and Catholics followed, and Protestantism survived in Switzerland. Zwinglianism, however, did not survive, being replaced by Calvinism in the Swiss Reformed Church. Still, Zwingli was important for establishing Protestantism in Switzerland and serving as an example for the more successful Calvinists who followed.

Grassroots Protestantism: the Anabaptists

After breaking the Catholic Church's centuries long monopoly on religion, the issue arose of how far beyond the old set of rules the new beliefs could go. Luther, Zwingli, and Calvin, despite significant religious differences, drew up new sets of rules fairly close to the Catholic Church's. Among other things, they all believed in obedience to civil authority. However, some men preferred to go much further in rewriting the rules. As a result, some 40 different religious sects sprang up in Western Europe. Although their beliefs varied somewhat from one another, they have been lumped together under the name of Anabaptists from their common practice of baptizing members as adults when they could make the free choice to be Christians. In addition to the Bible as a source of religious truth, they also believed in inner revelation coming directly from God.

The Anabaptist movement was more involved with social discontent than the other Protestant sects were. The 1500's saw economic difficulties resulting from rising population and inflation. Peasants, town craftsmen, and miners were especially hard hit, and it was they who especially joined the Anabaptist ranks in hope for a better world to come. Most Anabaptists denied the right of civil governments to rule their lives. They refused to hold office, bear arms, or swear oaths, which naturally made the authorities suspicious of them.

Actually, most of the Anabaptists were just trying to live good, peaceful; Christian lives in imitation of Christ himself. They did not openly resist the authorities, but they still aroused suspicion because of their different ways. Some groups held property in common. Others went to extremes in interpreting the Bible literally, preaching from rooftops and even babbling like children as the Bible supposedly told them to. They tended to separate themselves from the rest of society, which they saw as sinful. Despite their peacefulness, the Anabaptists were heavily persecuted. This forced them to migrate, which spread their beliefs from Switzerland down the Rhine to the Netherlands. It was here that the movement turned more violent as it combined frustration from economic hard times with an older tradition of socially revolutionary ideas that were popular among the peasants. The climax of this process took place in the German city of Munster in the early 1530's.

It was in Munster that radical Anabaptists seized power and combined religious fanaticism with a reign of terror that tarnished the reputation of other Anabaptists for years. All books except the Bible were burned. Communal property and polygamy were enforced. Their leader, John Bockleson, ruled with a lavish court while ensuring his followers that they too would eat from gold plates and silver tables in the near future. So alarming was this spectacle that Lutherans and Catholics combined forces to snuff it out. The determined and disciplined resistance of the Anabaptists led to a drawn out siege (1534-35). The city was finally betrayed and the Anabaptist leaders exterminated. An intense persecution of the Anabaptists followed, killing thousands and driving many more from place to place. Some of them, such as the Mennonites and Amish, found a home in North America and have had a profound influence on our attitude of separating church and state. Others made their way to the Spanish Netherlands where they helped stir up a major revolt against Catholic Spain.

The English Reformation

As discussed above, the strong medieval monarchies of France, England, and Spain assumed more and more control over the Church within their own lands. As a result, these kings had few grievances against the Church and were generally hostile to the Reformation, since it threatened their own control of religious policies. They were also strong enough to repress the spread of Protestantism among the lower classes. However, the Reformation found a home in one of these monarchies, England, thanks to some very peculiar circumstances.

Henry VIII of England had been given the title of "Defender of the Faith" by Pope Clement VII for a work he had written attacking the Lutherans, mainly on political grounds. However, just as at one point he defended the Church for largely political reasons, at a later date, Henry broke with the Church, also for political reasons.

Henry had a problem: he needed a son to succeed him to the throne. Without such a son, England might plunge back into civil war like the Wars of the Roses that Henry's father had ended in 1485. Henry's wife, Catherine of Aragon, had borne him a daughter, Mary, but no sons. Since Catherine was getting older, Henry wanted his marriage annulled so he could find a new wife to bear him a son. Unfortunately, Catherine was the aunt of the Hapsburg emperor, Charles V. Naturally he wanted Catherine to remain as Queen of England in order to influence its policies and possibly get control of the throne herself. Since Charles also controlled the pope, the annulment was refused. Meanwhile, Henry had fallen in love with a young woman of the court, Anne Boleyn, giving him more reason to dispose of Catherine.

Only twenty years earlier, Henry would have had to accept this verdict or resort to violent means to solve his problem. Ironically, the Lutherans that Henry despised provided him with an answer to his problem: break with Rome. However, he had to move quickly, because Anne was with child and Henry wanted the baby, hopefully a boy, to be born after the break with Rome in order to be legitimate.

In 1533, Henry started to break England's ties with the Catholic Church. He was clever in how he accomplished this, doing it in stages, first by cutting off money to Rome, then curtailing the power of the Church courts and assuming more authority over the English clergy. Also, he did this through Parliament so it would seem to be the will of the English people rather than the mere whim of the king. In 1534, he severed the last ties with Rome, and the Church of England replaced the Catholic Church. All this took place in time for the birth of the baby, which turned out to be a girl, Elizabeth.

The average churchgoer in England would have noticed little difference in the dogma and service as a result of this break, since the Church of England was basically the Catholic Church without a pope. Therefore, most people accepted it since there were no drastic changes, they resented Church abuses, and feared a civil war if Henry died without a male heir.

After Henry's death, his nine-year-old son, Edward VI, the son of Jane Seymour, one of Henry's later wives, took the throne. During his brief reign, the nobles ruling in his name followed Protestant policies. However, when Edward died in 1553, his older half sister, Mary, came to the throne. She was an ardent Catholic like her mother, Catherine. She even married Philip II of Spain to enforce her Catholic policies. The main effects of Mary's persecutions were to alienate the English People, make them more firmly Protestant, and earn her the title of Bloody Mary.

When Mary died childless in 1558, her half sister, Elizabeth I, succeeded her. This remarkable woman, one of England's ablest and most popular monarchs steered an interesting course between Protestantism and Catholicism. The English, or Anglican, Church under Elizabeth grafted moderate Protestant theology on top of Catholic organization and ritual. This compromise satisfied most people, but the more radical English Calvinists wanted more sweeping reforms, such as doing away with bishops and archbishops altogether. These people were known as Puritans, since they wanted to purify the Anglican Church of all Catholic elements. Their numbers and power would continue to grow throughout Elizabeth's reign, although she was able to control them.

In addition to England's navy saving European Protestantism from extinction at the hands of the Spanish Armada in 1588, the English Reformation was important for opening the way for the more radical Puritans Calvinists to filter in. Eventually, they would become influential enough to overthrow the pro-Catholic king, Charles I, and establish a parliamentary democracy. This in turn would inspire the spread of democratic ideals to America, Europe, and the rest of the world.

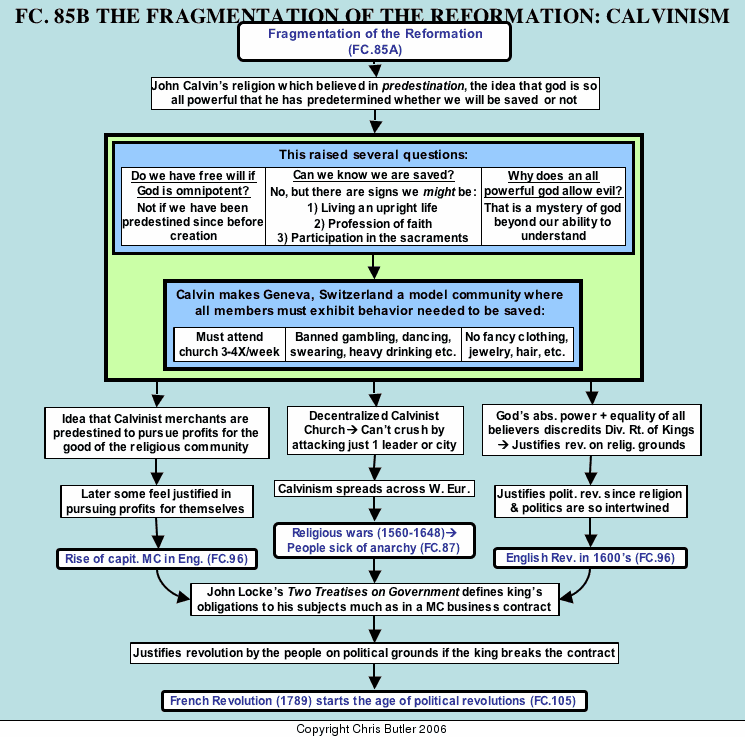

FC85BThe Reformation Fragments II: Calvinism

Introduction

As important as the Zwinglian, Anabaptist, and English reformers may have been, it was Calvinism that would have the most profound and revolutionary impact on Western Civilization. Although the Calvinists' primary concerns were religious, their reforms would radically alter the political and economic institutions of Europe, helping lay the foundations for the eventual triumph of capitalism and democracy.

Luther's break with the Church was especially difficult since he had grown up without any religious alternatives to Catholicism or examples to follow in his reforms. The next generation of reformers, led by John Calvin, grew up in a world that offered alternatives to Catholicism, thus making it easier to break with the Church and carry religious reforms much further than Luther ever had.

Calvin himself grew up in France as the first shock waves of the Reformation rocked Europe. Although not officially allowed in France, Protestant ideas still filtered across the border and won converts. Unlike Luther, whose tormented soul provides fascinating reading, Calvin was a much calmer individual. He seems to have been plagued by none of Luther's self doubts and his personal character was described as nearly flawless. After receiving a good education in theology, law, and also humanist studies, which prompted him to read the Bible more carefully, he seems to have arrived at some sort of conversion in 1533.

Calvin's religion

The cornerstone of Calvin's theology was God's all encompassing power and knowledge. There was nothing God did not know or have control of: past, present, or future. As a result, God knew and controlled from the beginning of time whose souls would be saved or condemned for eternity. This doctrine, known as predestination, had scriptural support and was a logical outgrowth of what Luther had said about faith and salvation being a free gift of God. Predestination raised several disturbing questions. First of all, if God were all-powerful, could we have any free will in choosing between God and Satan? Quite bluntly, Calvin said no. Second, if God were good, how could he let evil exist in the world? Calvin answered that these were mysteries of God that we cannot know the answers to and probably have no business asking.

Finally, can we know we are saved and how? According to Calvin, there is no way for us to know for sure. However, if we meet the requirements of living an upright life, profession of faith, and participation in the sacraments, we could become pleasing to God and be saved despite our sinful nature, if predestined to do so. Such a puritan lifestyle might not ensure salvation, but it could be a sign that one might be one of the few elected by God to go to heaven. However, Calvin said our primary concern should not be going to Heaven, but rather carrying out God's plan for us in this life. As fatalistic as Calvinism with its denial of the existence of free will may sound, its adherents felt empowered by this idea that they were the special instruments for carrying out God's plan. This gave them an unshakable faith in the utter rightness of their cause and made Calvinism the most dynamic movement of its day.

Calvin's Institutes of the Christian Religion, published in 1559, became one of the most popular and influential books of its day. However, Calvin went beyond words in trying to make a point about his religion. To ensure that as many people as possible had a chance to be saved, he established a model Church and community in Geneva, Switzerland to enforce the proper lifestyle needed for salvation. Naturally, Calvin's reforms met resistance and it took him nearly twenty years to get control of Geneva and reform it.

Although the city government still functioned, the Consistory, a church council of twelve elders, wielded the real power over people's lives in Geneva. All citizens were members of the church and had to attend services three or four times a week. This was because there was no telling who was predestined to be saved, and so all must be given a chance. Such acts as fighting, swearing, drunkenness, gambling, card playing, and dancing were outlawed. Even loud noises and laughing in church were fined. Theaters and taverns were closed and replaced by inns allowing moderate drinking accompanied by sermons and church propaganda. Members of the Consistory would make annual inspections of homes to ensure they were morally run. People were even expected to report their neighbors for any behavior that was less than saintly.

The Consistory also ruled the more trivial aspects of peoples' lives. Jewelry and lace were frowned upon, the color of clothing was regulated by law, and women were fined for arranging their hair to immodest heights. Children were to be named after Old Testament figures, and one man was jailed for four days for naming his son Claude instead of Abraham. Punishments were equally harsh, with fifty-eight executions between 1542 and 1564, mostly for heresy (especially Catholicism) and witchcraft. Fourteen witches were burned in one year and one boy was beheaded for striking his parents. Not surprisingly Geneva was called "City of the Saints".

Geneva served as a model to other reformers in Europe, helping make Calvinism the most popular form of Protestantism in the Netherlands, Scotland, and England. This was in spite of its lack of support from rulers who feared both Calvinism's emphasis on God's absolute power, which might undercut the doctrine of Divine Right of Kings, and its lack of being associated with any particular nation. In Germany and Scandinavia, Lutheranism was quickly identified with strong nationalist sentiments that rulers could exploit for their own political purposes. However, Calvinism had no particular national ties, thus depriving it of the strong state support that Lutheranism enjoyed.

However, this lack of state support forced Calvinists to form independent local congregations without any real central organization, making it virtually impossible to uproot and destroy their movement by concentrating on a few leaders. These congregations were somewhat democratic, thus inspiring greater loyalty in all their members, even when facing intense persecution for their beliefs.

Long range effects of Calvinism

Two of Calvin's ideas would have far reaching effects going far beyond religion. First, the idea of predestination meant not only that Calvinist merchants were allowed to do business and make money, they were predestined to do so and should do so fervently as God's will. Of course, as devout Calvinists, they were to make money for the good of the church and community, and at first that was what they did. However, later generations, lacking the intense fervor of the first generation of reformers (a normal pattern with any revolutionary movement), came to feel justified in pursuing profits for their own personal good. The result of this was the triumph of capitalism, especially in England and the Dutch Republic where Calvinists predominated, as the dominant economic system in Western Europe. This in turn would make Western Europe the economic center of the world and home of the Industrial Revolution.

The second Calvinist far-reaching effect of Calvinism was the concept of God's absolute power that, along with the idea that God sees all useful occupations as equal, discredited the doctrine of Divine Right of Kings. Calvin himself preached obedience to authority unless religious conviction forced civil disobedience. But it should never involve open resistance, since God alone would punish any evil rulers. However, some Calvinists, such as John Knox, the fiery leader of the Scottish Calvinists, preached people could overthrow a corrupt prince to defend their religious beliefs and God's law. The revolt of the Spanish Netherlands (1566-1648) and the English Civil War (1642-45) were two prime examples of such Calvinist religious revolts.

Later, these two ideas, capitalism and religious revolution, combined into an even more powerful idea discussed in John Locke's Two Treatises on Government (1694). Much as middle class contracts define obligations in a business deal, Locke saw government as an implied contract especially defining obligations for the king who acted as caretaker of the state for the good of the people, protecting their lives, liberties, and property. If the king failed in these duties, the contract was null and void and the people had the right to overthrow him. This combination of middle class contracts and the belief in religious revolution would become the cornerstone of democracy. And within that idea lay the seeds for the democratic revolutions that would sweep through France, Europe, and eventually the entire globe in the 1800s and 1900s.

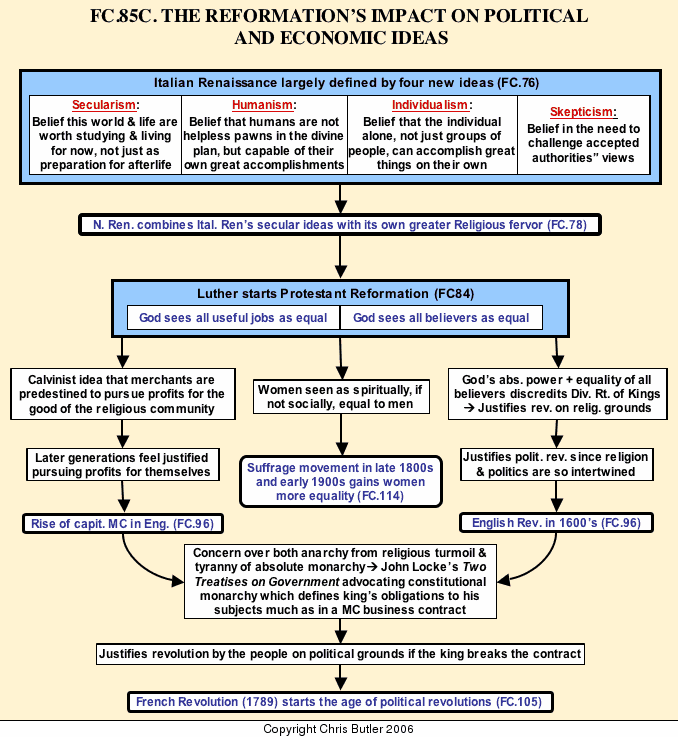

FC85CThe Reformation's impact on political ideas

Few things in history take more devious twists and turns from their origins than ideas, and few ideas have taken more devious twists and turns than how those of the Protestant Reformation helped lead to such things as the triumph of capitalism, democracy, and women’s rights. In fact, to fully understand this progression of ideas, we need to go back to the Italian Renaissance and the four major ideas that came from it:Secularism: the belief this world and life are worth studying and living for now, not just as a preparation for the afterlife;

Humanism: the belief that humans are not helpless pawns in the divine plan, but capable of their own great accomplishments;

Individualism: the belief that individuals alone, not just groups of people, can accomplish great things on their own; and

Skepticism: the belief we should challenge accepted authorities views, rather then blindly accept them.

When these ideas made their way out of Italy and combined with the more religious attitudes of the Northern Renaissance, they helped lead to the Protestant Reformation. Two of Luther’s ideas would have dramatic and unforeseen effects: the beliefs that God sees all useful jobs as equal and all believers as equal.

While Luther also believed in pre-destination, it was Calvin who especially emphasized it. That combined with the idea that all useful jobs are equal led to the conclusion that if one is a merchant, it is because he was predestined to be a merchant. Therefore, it was God’s will that he work hard to earn profits for the good of the church and community. However, as religious fervor cooled over succeeding generations, Calvinist merchants started keeping more and more of their profits for themselves. Eventually, some merchants would lose all their religious fervor, leaving only a fervor for profits, which we still refer to as the Protestant work ethic, and the triumph of capitalism in Northwestern Europe.

The idea that God sees all believers as spiritually equal also had surprising repercussions through the succeeding centuries. For one thing, the idea of spiritual equality was seen as applying to women as well as men, but not in the political or social sense…. at first. A major, though little noted, turning point came in the 1600s with a Protestant sect known as the Quakers. They figured that, if women were spiritually equal, they should have the right to preach. However, the church was the center of their social life as well, and women assumed a more prominent place in Quaker society overall. Fast forward two centuries to 1848 and the Seneca Falls Conference, which was the start of the women’s suffrage movement in America. Of the five women at that conference, three were Quakers who would take the lead in gaining women the vote.

The spiritual equality of all believers also had profound political effects in another way. The reasoning was that, if all believers and the jobs they do are equal, which would discredit the quasi-religious status of rulers and the doctrine known as the Divine Right of Kings. Calvin said that if people were religiously repressed and kept from worshiping God in the proper manner, they had the right to resist, but only non-violently through civil disobedience. It didn’t take long for a Calvinist leader in Scotland, John Knox, to extend this to justifying revolution on religious grounds. The problem was that religion and politics were so intertwined that a religious revolution had major political implications as well. This mixture of religious and political issues played out in nearly a century of religious wars that raged across the Netherlands, France, Germany, and England.

The English Revolution (1603-88) also saw economics mixed in with religious and political issues. In 1694, the rise of a capitalist middle class and triumph of democratic principles (in a very limited form) led a remarkable book by John Locke, Two Treatises on Government, which summarized what that revolution had been about. Locke saw government, in typically capitalist fashion, as an implied contract between the ruler and subjects where each had mutual rights and obligations, as opposed to everything existing for the benefit of the ruler. The people owed their ruler obedience, but he was obligated to protect three things: their lives, liberties, and property. If the ruler failed to live up to these terms, the contract was null and void, justifying revolution on purely political grounds. Thus, less than two centuries after the start of Luther’s reformation, his purely religious ideas about the equality of believers and their jobs had transformed into ideas justifying political revolution on purely secular grounds.

In 1776 the American Declaration of Independence would merely restate Locke’s ideas, substituting “pursuit of happiness” for property. The “Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen” in 1789 during the French Revolution wouldn’t even diverge that far and would inspire revolutions across Europe and the globe over the next two hundred years.

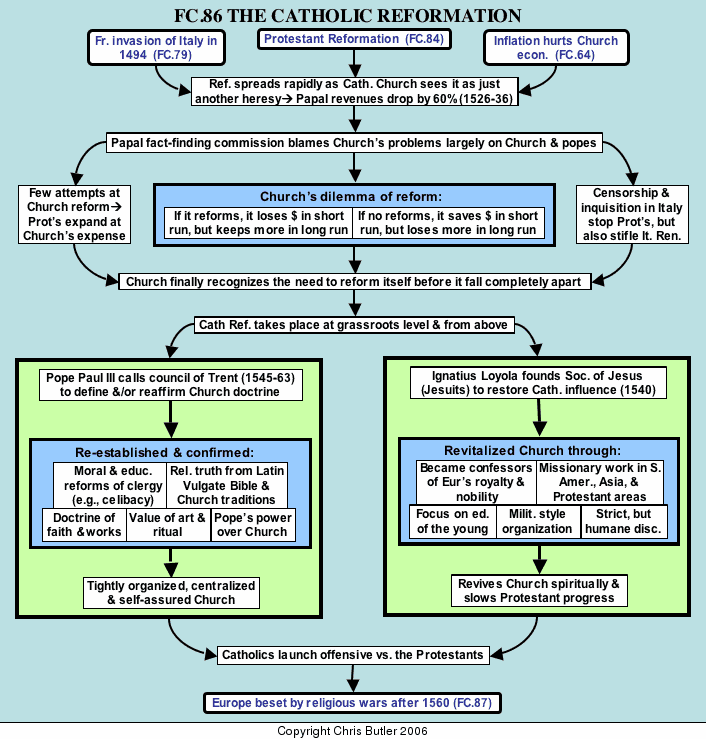

FC86The Catholic Reformation

One must remember that the Protestant reformation had only limited success. The two most powerful monarchies in Europe, Spain and France, remained Catholic, as did Austria, Italy, Portugal, Hungary, Poland and parts of Germany. Still, Protestant success had been rapid and posed a serious threat to the Catholic Church. As a result, the Church went through its own Catholic Reformation, also known as the Counter Reformation, in which it reformed itself, defined its theology, reestablished the pope’s authority in the now reduced Church, and prepared for a counter-offensive against the Protestants.

Early reactions by the Church to Protestantism

The Church had often been challenged with criticism in the past, but each time had patched things up with internal reforms. Therefore, at first it saw Protestantism as just another protest that a few reforms could mend and failed to recognize the deep philosophical and religious issues involved. Since many Church abuses were the result of the financial problems deeply rooted in the later Middle Ages, maybe it was too much to expect reforms of abuses at this time. However, those problems only got worse in the 1500s. Inflation, loss of lands and revenue to the Protestants, and invasions of Papal lands left Pope Paul III with only 40% of the revenues his predecessor had jus ten years earlier. As difficult as it would be, the threat of further losses to the Protestants made reforms all the more necessary. In 1536, Pope Paul III established a fact-finding commission to find out why there was so much protest and what could be done about it. The resulting report, Advice on the Reform of the Church, blamed the Church for many of its problems and called for reforms that would convince the Protestants to rejoin the Church. Two things resulted from this report. First, the Church failed to accept responsibility for its problems, making what few reforms that result only half-hearted. Consequently, Protestantism kept expanding.

The second result was that the Church, rather than trying to reform itself, decided to attack its enemies. In 1542, the pope brought the Inquisition into Italy, giving the Inquisitor general authority over all Italians. This effectively uprooted any elements of Protestantism in Italy and restored the pope’s authority over the whole peninsula. To a large extent, the Inquisition helped put an end to the Italian Renaissance, since it suppressed Italy’s vigorous intellectual life for the sake of conformity to the Church. Remarkable individuals, such as Galileo, might still come along, but they would face the Inquisition’s repression for any new ideas they might propose. The Church was also waking up to the dangers that a free press presented to the established order. In 1543, the Inquisition published the first Index of Prohibited Books, the first full-scale effort to limit or destroy the free expression of ideas through the press. It would not be the last. Among its victims was the report Advice on the Reform of the Church, since it was seen as giving solace to the Protestants and their ideas.

However, by the mid-1540s, it was becoming increasingly apparent that the Catholic Church would have to institute serious reforms if it were to halt the rising tide of Protestantism. These reforms came from two directions: the Papacy at the top and the grassroots (popular) level below.

Reform from the top: the Council of Trent (1543-63)

One problem facing the Church was the wide variety of interpretations people had of the Bible and other Church writings. This was not a new problem, but it became an urgent one when faced with competing Protestant interpretations. Consequently, Pope Paul III called a general Church council that met at Trent, Italy to define decisively what the official doctrines of the Church were. People remembered the threat to the pope’s power that councils had posed during the Great Schism a century earlier. Naturally, the pope was nervous about this and tried to restrict the council to working on Church doctrine instead of reforms that might threaten his position.

The Council of Trent met in three sessions from 1543 to 1563. Popular hopes focused on the desire to restore Christian unity, since Protestant representatives were supposed to attend (but never did). Even if it did not achieve such unity the Council did revitalize the Catholic Church and restore the pope’s power within the Church. It strictly defined religious doctrine. It emphasized the role of both faith and good works in achieving salvation. It declared the Latin Vulgate Bible the only acceptable form of scripture, thus excluding any vernacular translations. It also reaffirmed the validity of all seven Catholic sacraments and the writings of such Church Fathers as St. Augustine as sources of religious truth. It kept the elaborate ritual and decoration of the Church, since they were inspirational for the mass of illiterate Catholics with little or no understanding of Church dogma. It also enacted various reforms, ensuring clergy were better educated and their morals better supervised. The pope was even able to restore his authority over local church and clergy at the kings’ expense.

Although the Council of Trent did not peacefully restore Christian unity, it did reestablish the authority of the popes within the Catholic Church, giving it the power to launch an offensive against the Protestants to reclaim formerly Catholic lands. Also restoring the Church’s spirit was a new religious order: the Society of Jesus, commonly known as the Jesuits.

Reform from below: Ignatius Loyola and the Jesuits

The Jesuits’ founder, Ignatius Loyola, (1491-1556) was quite similar to Luther in how he achieved inner religious peace, although the two men arrived at some very different conclusions about their respective faiths. Loyola was born a Spanish noble and, like Luther, had no initial plans for a religious career, being a soldier by profession. Also, like Luther, a somewhat dramatic event turned his life to religion. Instead of lightning, it was a leg broken by a cannonball while defending a fort that forced him into a long period of convalescence and ultimate conversion. Instead of the tales of war and chivalry that Loyola liked, the only reading material available was religious in nature. Eventually, this literature had its effect. Loyola experienced an intense conversion and decided to devote his life to Christ.

Like Luther, Loyola almost killed himself trying to purge his guilt. He finally obtained some inner peace by deciding the Devil was responsible for any self-doubts and despair one had for sins he had already confessed to the Church and done penance for. Loyola developed a four-week long set of spiritual exercises help others achieve similar inner peace. These exercises first had people contemplate their sins and their eternal consequences in Hell for two weeks, then contemplate Christ’s life, sacrifice on the Cross, and resurrection for a week, and finally contemplate the final ascension into Heaven.

After a pilgrimage to Palestine, Ignatius decided to get an education in order to preach more effectively. In school he gathered a loyal core of followers, the most famous being Francis Xavier. In 1536, they went to Rome determined to win souls, not by the Inquisition or the sword, but by educating people, especially the young who are most impressionable.

In 1540, they founded the Society of Jesus, also known as the Jesuits. The order was organized along military lines with four ranks or classes. Members were expected to show absolute obedience to their superiors, the pope and God. Instead of ascetic activities such as endless praying and whipping themselves, the Jesuits performed Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises and menial labor. Discipline was rigorous, but flexible, helping the Jesuits produce some remarkable leaders. The Jesuits also carefully selected their target audience from two main groups in society: nobles and children. As the confessors for royalty and nobles, they exercised considerable influence on religious policies within catholic states. They also ran numerous schools, believing that if they could influence children at an early age, they would remain loyal Catholics for the rest of their lives.

The order grew rapidly and became the virtual “shock troops” of the Catholic Church. They had missionary activities to South America (still mostly Catholic) and Asia. Within Europe, they spearheaded the Catholic reformation by strengthening the Church’s power in areas it still held while restoring allegiance in such areas such as Bohemia and parts of Germany.

With their Church on much firmer ground than before, many Catholics felt ready to go on the offensive against Protestantism. What resulted was a series of religious wars that would engulf Western and Central Europe for the next century.

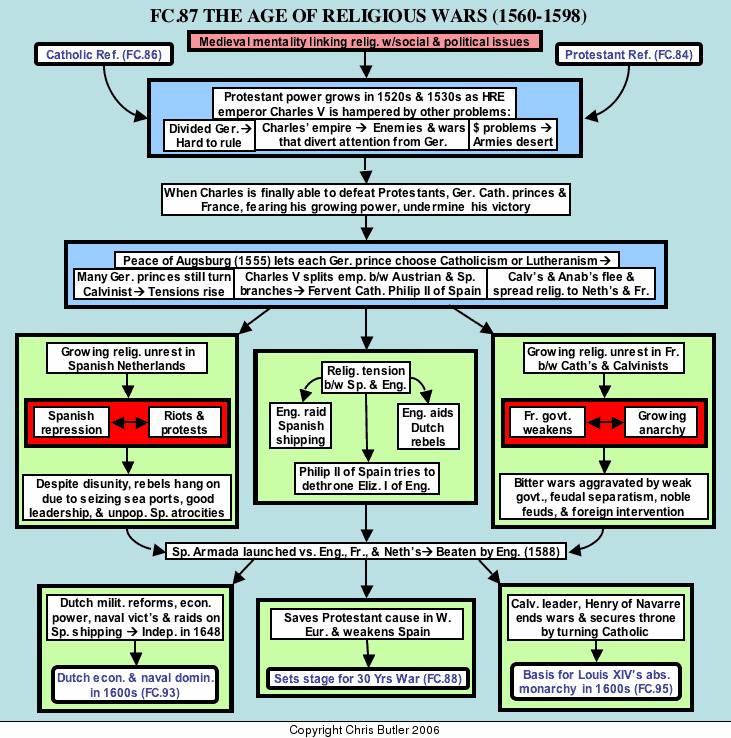

FC87The Age of religious wars (c.1560-98)

Kill them all; God will know his own.— Catholic general, ordering a massacre of a town containing both Protestants and Catholics

By the mid 1500's, three main factors were converging to push Western Europe into a century of brutal religious wars. Two of these were the Protestant and Catholic Reformations that were firmly opposed to each other. Added to this was a prevailing medieval mentality linking religion with political issues, making it impossible for either side to tolerate the other side's presence or rule. The first round started in Germany.

Germany (1521-55)

The emperor Charles V's dramatic confrontation with Luther at Worms in 152l had resulted in outlawing the Lutheran heresy. However, this was easier said than done for several reasons. First, Charles had little control over the Holy Roman Empire (Germany), a patchwork of over 300 principalities, Church states, and free cities, all jealously guarding their liberties against any attempts by the emperor to increase his authority over them. Charles could not even get effective support from the Catholic states to help suppress the Lutherans, since his success might give him more power over Catholic princes as well.

Second, the size of Charles' empire made him many enemies, in particular France and the Ottoman Turks, who posed a constant threat from west and east. As a result, Charles felt forced to let the Protestants alone and turn to more pressing matters on his borders. Finally, Charles was plagued with money problems. Several times in his career he found himself short of funds while on the verge of a major victory. In an age of mercenary armies prone to run out on their employers as soon as funds for paying them ran out, this was fatal and forced him to let his enemies, especially France, off the hook. All these factors kept Charles from effectively dealing with the Lutherans for over twenty years.

Therefore, it was 1546 before Charles could attack a defensive alliance of Lutheran princes known as the Schmalkaldic League. Charles won a decisive military victory. But the complex forces discussed above kept him from imposing either firm imperial control or his Catholic faith on Germany. Both Lutheranism and the privileges of the German princes were too deeply entrenched for that. Consequently, Charles agreed to the Peace of Augsburg in 1555, a compromise giving each German prince the right to choose his realm's religion, as long as it was either Catholic or Lutheran. Calvinists, Anabaptists, and other non-Lutheran Protestants were outlawed.

Instead of settling Germany's religious problems, the Peace of Augsburg actually made them worse in three ways. For one thing, Calvinism kept spreading across Germany, even among German princes, thus raising religious tensions even more. Also, Charles V, worn out by over 30 years of trying to maintain his empire and religious unity, gave up his throne. The family lands in Austria and the Imperial title went to his brother Ferdinand, while Charles' son, the staunchly Catholic Philip II, inherited Spain, the Netherlands, most of Italy, and Spain's American colonies. Philip's passionate hatred of the Protestants would also aggravate the growing religious conflict brewing. Finally, the Peace of Ausgburg led to thousands of refugees, especially Calvinists and Anabaptists, fleeing Germany and spreading their religious beliefs to the Spanish Netherlands (modern Belgium and Holland), France, and eventually England.

As a result, religious conflict spread to these three countries after 1560. In the Spanish Netherlands the influx of Protestants created growing religious unrest that led to a pattern of Spanish repression, riots and protests in response, more repression, and so on. Despite its disunity, the ensuing revolt would hang on due to its control of seaports in the North, good leadership, and anger against Spanish atrocities. In France, rising tensions between Calvinists and Catholics triggered its own vicious cycle of weakening the government, which allowed more anarchy, further weakening the government, etc. Coming from this was a series of bitter civil wars aggravated by the weak government, feudal separatism, nobles’ rivalries, and foreign intervention, especially by Spain. Finally, tensions between Protestant England and Catholic Spain led the English to raid Spanish shipping and support the revolt in the Spanish Netherlands while Philip II conspired to dethrone Elizabeth I.

The critical turning event in all three of these conflicts was the defeat of Philip II's Spanish Armada (1588) that was aimed against the Dutch and French Calvinists as well as England. While this did not destroy Spain as a power, it did save Protestantism in Western Europe, thus setting the stage for the Thirty Years War. It also helped the Dutch win their freedom (1648) and become the premier naval and trading power in the 1600's. Finally, it allowed the Calvinist leader, Henry of Navarre, to take the throne of France after placating his Catholic subjects by converting to Catholicism while ensuring religious freedom to the French Calvinists. This ended the French Wars of Religion so Henry IV could lay the foundations for the absolute monarchy of Louis XIV.

Revolt of the Spanish Netherlands (1566-1648)

The Spanish Netherlands was a collection of seventeen semi-independent provinces lumped together under Spanish rule. With the possible exception of Italy, they were the wealthiest trading and manufacturing area in Europe in the 1500's. Their main port, Antwerp, handled a full 50% of Europe's trade with the outside world. Charles V had been born there and was somewhat popular with the inhabitants. That was not the case with Philip II. It was said that Charles neglected the Spanish Netherlands, but his son, Philip, abused them. This was largely true, although Charles also heavily taxed the Netherlands for his wars and tried to impose his religious policies on them. The major difference was that Philip did it with a heavier hand and with little or no concern for the feelings of his subjects there.

Philip was Spanish born and never left his homeland after his coronation in 1556. His view of the world was very Spanish and very Catholic. He taxed the Netherlands to pay for Spanish wars and he claimed he would rather die a hundred deaths than rule over heretics. As it was, Anabaptist and Calvinist "heretics" were making their way into the Netherlands, especially after the Peace of Augsburg outlawed them in Germany. Philip, determined to get them out, brought in the Inquisition and increased the number of bishops the Netherlands had to support from four to sixteen. This repression started a cycle that led to protests and riots, more Spanish repression and so on until rebellion broke out. This rebellion would drag on until 1648, become part of the wider European struggle known as the Thirty Years War, and itself become known as the Eighty Years War.

In 1566, the Duke of Alva with an army of 10,000 Spanish troops established the so-called "Council of Blood" which burned Calvinist churches, executed their leaders, and raised taxes to levels ruinous for trade, and nearly extinguished the revolt. However, despite the disunity of the revolt itself, it managed to survive for several reasons. First, Calvinist raiders, known as "Sea Beggars", managed to gain control of some ports in the North. When word of these Calvinist havens spread, more Calvinists flocked in. As a result of this migration, Holland in the north became and remains primarily Protestant today. The second reason was the rebels' leader, William, Prince of Orange, called "the Silent" for his ability to mask his intentions. Although a mediocre general, William was a brave and patriotic leader whose selfless determination gave the revolt what little cohesion it had. His accomplishment, much like that of George Washington in the American Revolution, would be as much to keep the rebels together as keeping the enemy at bay.

Finally, Spanish attempts to crush the revolt of the Sea Beggars often alienated more people and made them go over to the rebels' side. This was especially the case in 1576 when Spanish troops in the loyal provinces to the south rioted and went on a rampage of looting and slaughter in Antwerp after going unpaid for 22 months. (However, they were pious enough to fall to their knees and pray to the Virgin Mary to bless this atrocity.)

Fighting in the war itself was desperate and destructive. The siege of Maastricht in 1579 involved vicious battles in the miles of underground mines and countermines dug around the city. When Spanish troops finally poured in through a breach in the wall, a slaughter ensued which killed all but 400 people out of a population of 30,000. At times the rebels had to stop Spanish invasions by opening up their dikes and literally flooding the enemy (and their own crops) out. At the siege of Leyden, this was done also to provide water on which the Dutch rebels could float relief ships full of grain right up to the walls of the city. The city held out, but only half of its inhabitants survived the rigors of the siege, having subsisted on boiled leaves and roots, wheat chaff, dog meat, and dried fish skins. Interestingly enough, it was not until 158l that the Dutch rebels formally deposed Philip II as their king and declared the Dutch Republic in the Oath of Abjuration, a document that would strongly influence the American Declaration of Independence and later democratic movements.

Philip's efforts to establish Catholic rule in England and France got the Netherlands involved in the wider scope of European religious wars. Troops from England helped the rebels, as did the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, which was aimed against the Dutch and French Calvinists as well as England. After Dutch advances in the 1590's and early 1600's, the two sides signed a twelve years truce in 1609. However, the Dutch continued to blockade the Scheldt River and cut off Antwerp's trade. Gradually, this trade shifted to the Dutch city of Amsterdam, thus making it the new commercial capital of Europe. Hostilities resumed in 1621 as part of the wider conflict known as the Thirty Years War. Gradually, growing Dutch economic power and Spanish exhaustion from constant warfare turned the tables in favor of the Dutch. In 1628, the Dutch captured the entire Spanish treasure fleet. In 1639, they crushed another Spanish Armada at the Battle of the Downs and ended Spanish naval power once and for all.

After eighty years of struggle, Spain finally recognized Dutch independence in 1648 in the Treaty of Munster. At this point, the Dutch were at the height of their commercial and naval power, although England would challenge them for that position in the later 1600's. The southern provinces would remain under Spanish, then Austrian, and finally Dutch rule until they won their freedom in 183l and established the modern nation of Catholic Belgium in the south.

The French Wars of Religion (1562-98)

France was another country that saw the devastating effects of religious wars in the last half of the 1500's. In this case, the antagonists were the Catholic majority of France and a strong minority of French Calvinists known as Huguenots. Although only comprising about 10% of France's population, the Huguenots had several factors that helped them maintain their struggle for over thirty years. Their number included many nobles who provided excellent leadership. They were concentrated largely in fortified cities in the south. Finally, they were enthusiastic and well organized into local congregations.

For thirty years Catholic and Huguenot armies marched across France destroying its fields and homes. All this bred a cycle of chaos and destruction where growing anarchy would steadily weaken the French government's power, thus allowing even more anarchy and so on. There were actually seven French religious wars with intermittent periods of peace, which made these wars & this period of French history confused, chaotic, and bloody.

Once the wars started, they tended to drag on and were aggravated by several factors that made them especially destructive. First of all, besides the religious struggles, fighting between noble factions and revolts by old feudal provinces exposed and added to the weaknesses of the French state. Second, foreign intervention, especially by Spain, but also by other states such as England, compounded the turmoil and destruction. Finally, France was ruled by weak monarchs who let these forces tear the country apart.

The fighting was confused and often involved the massacres of women and children. From 1562-157l there were eighteen massacres of Protestants, five massacres of Catholics, and over thirty assassinations. The most famous such event was the Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre (8/24/1572), when the Paris Catholics suddenly burst upon local and visiting Calvinists and killed some 3000 of them. A letter from a Spanish ambassador shows the degree of fanaticism and viciousness that infected peoples' minds and values then: "As I write they are killing them all, they are stripping them naked...sparing not even the children. Blessed be God."

Philip II added to the disorder by actively supporting the Catholics. The turning point came with the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, which led to a series of assassinations. First, the king, Henry III, assassinated the Catholic leader, Henry of Guise. Then, a fanatical monk assassinated the king for what he saw as his betrayal of the Catholic cause. The man in line to succeed Henry was still another Henry, duke of Navarre, who also happened to be the Huguenot leader. The prospect of a Calvinist king did not set too well with the predominantly Catholic population of France and led to even more fighting. Despite brilliant victories against heavy odds, Henry still faced the desperate resistance of the Parisians, whose priests told them it was better for them to eat their own children than let them live under a Calvinist king. When confronted also with Spanish intervention to put a Catholic back on the throne, Henry somewhat cynically converted to Catholicism to give his Catholic opponents no more reason to attack him.

Despite Henry's obvious political motives and the fact that he guaranteed Huguenot religious freedom by the Edict of Nantes (1598), Frenchmen were ready to accept him as king, since they were tired of constant warfare and wished only for peace. In order to ensure this, Frenchmen were willing to submit to the stronger rule of a king. This attitude helped set the stage for the rise of France as the dominant power in Europe in the later 1600's and the rule of one of its most glorious and absolute monarchs, Louis XIV, the Sun King.

Elizabethan England and the Spanish Armada

Certainly one of the most fascinating and capable monarchs of the age was Elizabeth I of England (1558-1603). We have already seen how she skillfully defused religious tensions in England by grafting Catholic ritual and organization onto mild Protestant theology, thus keeping most people reasonably content. Good Queen Bess, as she was known, was quite popular with her people, since she kept taxes low and knew how to get what she wanted from Parliament without being too demanding about it. She also kept the people's good will by acting as one of their own, patiently sitting through any pageants or speeches given in her honor. Elizabeth and her subjects understood and loved each other quite well. Her tolerant reign was a virtual golden age for England, nurturing among other things, the genius of William Shakespeare, possibly the greatest literary figure in its history.

Being a woman, Elizabeth had to be crafty to keep her throne, avoiding at all costs a marriage that would put a husband in her place as the real power in England. As a result, she never married, although she cleverly held out the prospect of marriage to neutralize potential enemies and keep them on their best behavior.

The great test of Elizabeth's reign was the war against Spain culminating in the Spanish Armada in 1588. The causes of the war revolved mainly around religious differences between Spain and England that caused various acts of aggression by each side against the other. Philip II still hoped fervently to re-establish Catholicism in England. Throughout the 1570's he plotted toward this end, trying to put Mary Queen of Scots, a Catholic, in Elizabeth's place. Elizabeth countered these intrigues by finally executing Mary after a long imprisonment. She also sent troops to help the Dutch rebels, while encouraging freebooting English captains, such as Sir Francis Drake, to raid Spanish shipping. Finally, Philip decided to crush the Protestants in England, Holland, and France by sending a huge armada (navy) and army northward in 1588.

Philip's plan was to send the Armada to pick up the Spanish Army of Flanders which was then fighting the Dutch, transport it to England to crush the English, and then transport it back to crush the Dutch rebels and French Huguenots. Thus the Armada presented a serious threat, not just to England, but also to the very existence of Protestantism in Europe.

On the surface, the struggle looked like an uneven one, heavily stacked in Spain's favor. However, the English had developed radical new tactics and ship designs that would revolutionize naval warfare. They built sleeker ships powered totally by sails. Instead of boarding and grappling, they relied on cannons fired from the broadside to destroy the enemy fleet. Recent research shows that the English enjoyed a decisive edge in firepower thanks to their use of shorter four wheeled carriages that made it easier to reload and fire the cannons. This contrasted with the Spanish who still used longer gun carriages adapted for land use. These had long trailers, which made it very difficult, if not impossible, to pull them inside the cramped quarters of the ship's gun deck for reloading during the heat of battle. These innovations successfully frustrated the Armada's attempts to come to grips with the English. However, the English, in turn, were unable to stop the Spanish advance up the coast for its rendezvous with the Army of Flanders.

When the Spanish pulled into the French harbor of Calais to rest, get supplies, and try to establish contact with the Army of Flanders (which through poor communications had no idea of its approach), the English struck. Launching eight fireships into the midst of the Spanish fleet, they forced the Spanish ships out into the open and out of formation where the English could use their superior firepower and speed to destroy the Spanish ship by ship. An ensuing storm added to the damage and forced the Spanish to give up on their rendezvous with the Army of Flanders and return home by sailing all the way around the British Isles. When the Armada finally came limping back home, a full half of it had been destroyed.

The defeat of the Spanish Armada did not destroy Spain as a great power. However, it did signal the beginning of the end of Spanish dominance of Europe. In the first half of the 1600's this process would accelerate as Spain wrecked itself by trying to maintain its power in an exhaustive and devastating series of conflicts, most notably the Thirty Years War (1618-48). As a result, a new balance of power would emerge in Europe. France would replace Spain as the main superpower, while the Dutch Republic and then England, despite their small size, would become the most dynamic naval and economic powers in Europe.

Europe's mentality would also change in the 1600's. Exhausted and disgusted by the seemingly endless religious wars and disputes, many people would take a more secular (worldly) view of things, seeing religion more as a source of trouble than comfort. By the late 1600's, these views would flower in the great scientific and cultural movement known as the Enlightenment.

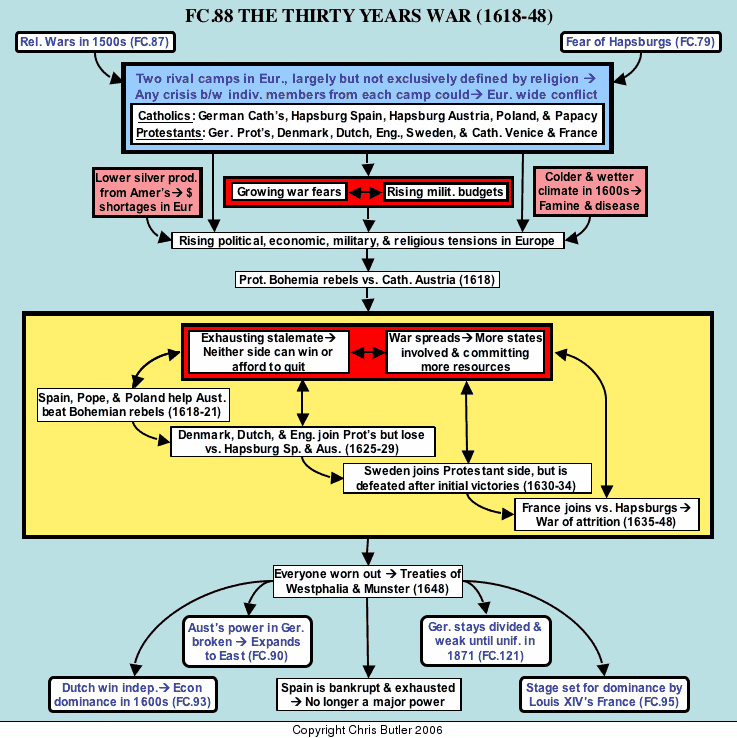

FC88An overview of the Thirty Years War (1618-48)

Introduction

The last half of the 1500's saw Europe embroiled in a number of religious conflicts. For the most part, these wars were either between two countries (e.g., England vs. Spain, the Dutch vs. Spain) or internal affairs with some outside interference (e.g., France and Germany). However, as the seventeenth century dawned, religious and political tensions grew to encompass all of Europe in an interlocking network of states extending from Russia to England and from Sweden to Spain. These tensions exploded into what can be seen as the first European wide conflict in history: the Thirty Years War (1618-48).

Causes and outbreak of war

The roots of the Thirty Years War extended back to two main developments in the 1500's: the religious wars emanating from the Protestant and Catholic Reformations, and fear of Hapsburg Spain and Austria, who between them controlled nearly half of Western Europe. Religious tensions (complicated by political rivalries) led to conflicts between Lutheran Sweden and Catholic Poland, German Protestants and Catholics, and the Protestant Dutch and English against Catholic Spain. Fear of the Hapsburgs also contributed to the English and Dutch conflicts with Spain. In addition, France, once it had recovered from its own religious wars, increasingly took the lead against the Spanish and Austrian Hapsburgs who ringed its borders to the north, south, and east. Venice also had problems with Austria over pirates in the Adriatic.

All these tangled religious and political tensions of the early 1600's polarized Europe into two camps defined largely, but not exclusively, by religion. The Protestant camp consisted of German Protestants, Denmark, the Dutch Republic, England, Sweden, Catholic Venice, and Catholic France. The Catholic camp had German Catholics, Spain, Austria, the Spanish Netherlands, Naples, Milan, the Papacy, and Poland.

Two such hostile camps staring menacingly at one another led to the common fear and expectation of a general war embroiling all of Europe. As a result, kings and princes built up armies and fortifications in preparation for the coming war, which merely reinforced the other side's fears of war, triggering more military spending and so on. Travelers of the time noted how states all over Europe seemed to be armed to the teeth and ready for a fight. This was especially true in Germany where the Protestant princes formed a defensive league known as the Protestant Union in 1609 while the Catholic princes quickly answered with the Catholic League.

Added to this were two other factors making Europe's economy less vibrant than it had been in the 1500's. For one thing, the flow of silver from the Americas had passed its peak. For another, the climate turned colder, reducing crop yields and straining Europe's ability to feed its population (which had doubled since 1450). This, in turn, led to lower resistance to disease (including Bubonic Plague which made a comeback in the 1600's). The combination of soaring military budgets, declining silver production, and the effects of a colder climate led to rising tensions in Europe, both between different states and between social classes within individual societies.

These problems combined with the fact that Europe was split between two hostile political/religious camps meant that any conflict or crisis between individual members of each camp could drag in all the other members of their respective camps and trigger a European wide war. In this respect, the situation largely resembled the one that would drag Europe into World War I in 1914.

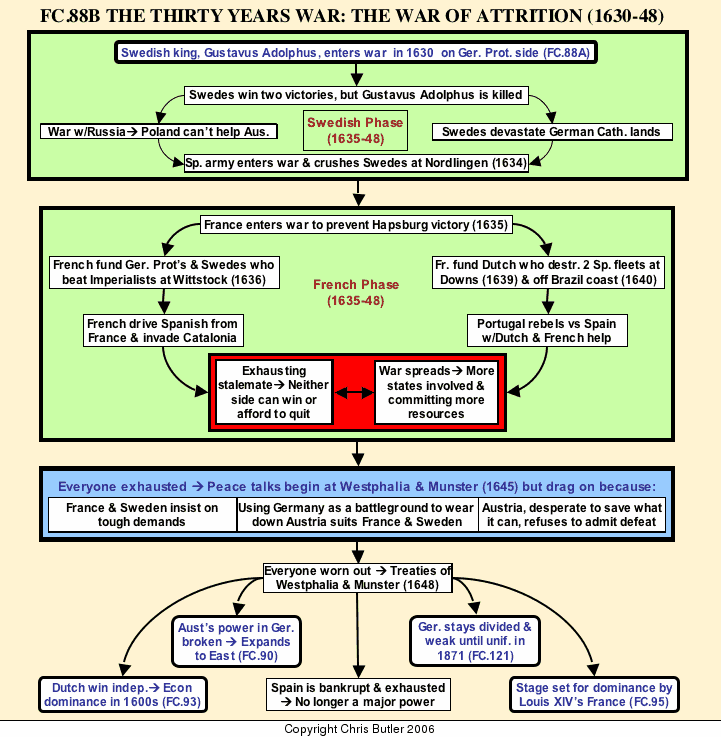

In 1618, Protestants in Bohemia, then part of the Holy Roman Empire, rebelled against the Austrian Hapsburgs. Unfortunately, Germany's fragmented political situation generated a vicious cycle that would turn a local struggle into a European wide conflict using Germany as its battleground. As the crisis grew, more states would get involved and commit increasing amounts of resources. As more allies joined each side, the war grew into an exhausting stalemate that neither side could either win or afford to quit since it had already spent so much on it and felt it had to recover its expenses from its enemies. Concern over a Protestant or Hapsburg Catholic victory and belief that the balance could be tipped to their advantage would draw in more powers, eat up more resources, perpetuate the stalemate, and so on.

Thus Spain, Poland, the German Catholics, and the Pope came to Austria's aid to crush the Bohemian rebels. This caused Denmark, England and the Dutch Republic to join the conflict against the Hapsburgs and were defeated. Then Sweden attacked Austria, supposedly in defense of the German Protestants, but was eventually defeated. Finally, Catholic France threw itself into the fray, helping the Protestants against the Hapsburgs. Each new power that would get involved merely fed more fuel into the veritable firestorm of continuing stalemate until there was hardly anything left to burn.

More and more, this has become the pattern of modern warfare, as its expense makes it too expensive to fight, but also too costly to back out once a country has committed itself to it. And as the cost and destructiveness of war goes up, the spoils of war to make it pay for itself dwindle correspondingly. This dilemma has increasingly plagued modern warfare to the present day as the technology of war has gotten progressively more destructive and expensive, both to build and use.

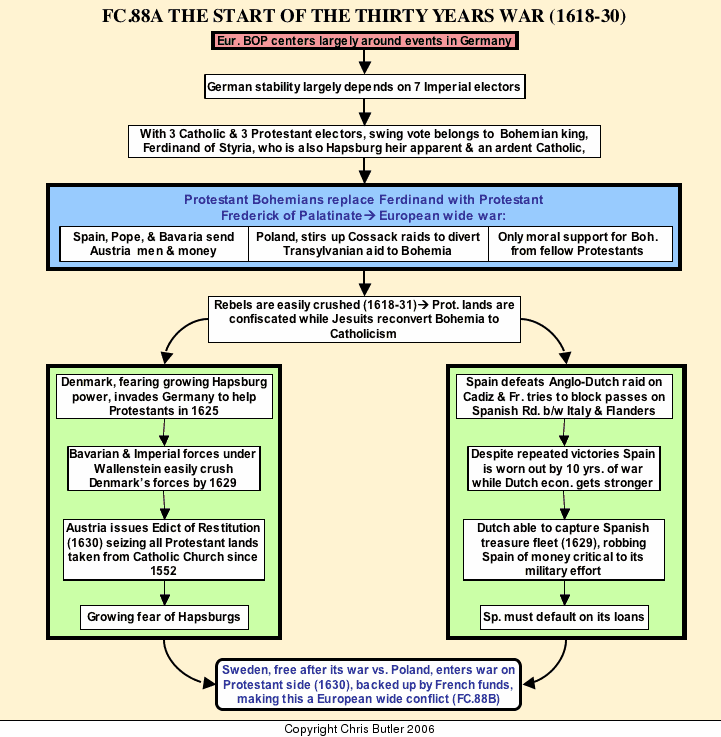

FC88AThe early stages of the Thirty Years War (1618-31)

Opening phases of the war (1618-35)