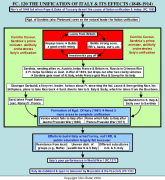

FC120: The Unification of Italy (1848-1871)

Flowchart

Italy

had last been unified under the Byzantine emperor, Justinian, some 1300 years before. Since then it had been a patchwork of states under Byzantine, Lombard, Norman, German, French, Spanish, and Austrian rulers. Political fragmentation brought economic and cultural fragmentation as well. Without standard gauges, railroads did not cross state boundaries, while numerous tolls and dialects also hindered trade.Italy's reunification, or Risorgimento (literally meaning resurrection), was largely the work of Camillo Cavour, prime minister of the north Italian state of Sardinia (also known as Piedmont). Although not a fiery or charismatic revolutionary leader, he was a cool and clear-headed diplomat and brilliant organizer, one of those realistic politicians who emerged from the failed revolutions of 1848. Cavour skillfully gathered popular support throughout the peninsula by exploiting Sardinia's position as one of the few native ruled states in Italy.

He also saw that Sardinia must be developed internally before it could make any moves against the Austrians, who controlled most of northern Italy, and the Bourbons, who ruled the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in the south. To that end he reorganized Sardinia's treasury, tax system, and bank system, and then got foreign loans, especially from Britain, in order to build railroads and industries. Careful management of these loans allowed him to turn a profit and pay off the loans, thus expanding Sardinia's credit for larger loans to further develop the economy and so on. By the mid 1850's Sardinia was the most highly developed state in Italy.

Cavour was now ready for the diplomatic offensive to unify Italy. His main opponent was Hapsburg Austria, against whom he realized he needed outside help. Oddly enough, in order to get this, he attacked Russia. This was during the Crimean War (1854-56), one of the more senseless and futile conflicts in history. It mainly involved French and British efforts to stop Russian aggression to the south against the Ottoman Turks. The fighting centered in the Crimean peninsula on the Black Sea where the British and French fleets could supply armies by sea better than Russia could supply its troops by land. It was a bloody and diseased affair, but it played into Cavour's hands, because Austria had angered France and Britain by refusing to help them against Russia. By sending Sardinian troops to help the French and British, Cavour won Napoleon III's friendship and the promise of French aid if he could make Austria appear the aggressor in a war.

Cavour had no trouble in stirring up rebellions against Austria and drawing it into attacking Sardinia. In the resulting War of 1859, Napoleon III sent 120,000 French troops to Italy by railroad, the first mass movement of soldiers by rail in history. The French won two battles, but suffered such heavy casualties that Napoleon III quickly pulled out, leaving Sardinia in the lurch. Despite this betrayal, the north and central Italian states of Tuscany, Parma, Modena, and Romagna rebelled against their rulers and unified with Sardinia, giving it about half of Italy's population. Events now moved quickly toward unifying the rest of Italy.

The price of Napoleon's aid against Austria was the transfer of Savoy and Nice to French control. This infuriated Giuseppe Garibaldi, a long time revolutionary leader who was as fiery and impulsive as Cavour was cool and calculating. Garibaldi had led the defense of the Republic of Rome in 1848 against French troops who still occupied it. Now the French were taking over Garibaldi's birthplace of Nice, and he intended to attack them there. But Cavour, still needing French diplomatic support, managed to divert Garibaldi and his army of 1000 "Red Shirts" to Sicily in order to overthrow the Bourbon dynasty. Garibaldi's tiny army met with incredible success and swept the Bourbons from Sicily in six weeks. They then crossed to southern Italy and swept the Bourbons from there as well. Practically overnight, southern Italy and Sicily had been liberated, but the question was for whom: Sardinia, who had sent Garibaldi, or Garibaldi himself who bore the title of dictator of southern Italy and Sicily while still wearing a Sardinian uniform?

Between Sardinia and Garibaldi lay the Papal States and Rome, the spiritual capital of Italy and still under French troops. Napoleon III, much preferring Cavour to Garibaldi, told the Sardinians to take the Papal states before Garibaldi got there, but to leave Rome to the French. Sardinia's king, Victor Emmanuel, did this and moved south to meet Garibaldi. In a dramatic meeting on October 26, 1860, Garibaldi turned his conquests over to Victor Emmanuel. The Kingdom of Italy was born.

Two important pieces of the puzzle remained to complete Italy's unification: Venice and Rome, held by Austria and France respectively. In each case, Italy's alliance with Prussia, then in the process of unifying Germany, proved to be valuable. In 1866, Italy won Venice by helping Prussia against Austria in the Austro-Prussian War. Likewise, Italian help in the Franco-Prussian War earned it Rome (except for the Vatican which remained an independent state inside of Rome). By 1871, Italy was unified.

But, as one politician put it, "Italy is made. We still have to make the Italians." After centuries of disunion huge cultural, political, and economic differences existed in this nation of 22 million people. The biggest gap was between the urban north and agricultural south. The Bourbons in southern Italy and Mafia in Sicily fanned discontent into revolts and violence exceeding that seen in the actual process of unification.

The new government did three things to pull Italy together. It built a national railroad system to physically links its parts. It established a national educational system to give its people a similar cultural outlook and loyalty. And it formed a national army to enforce its policies and also unify men from all over Italy in a common cause. However, 1300 years of disunity were a lot to overcome in a few years, and Italy's efforts at forging a nation met with limited success. Despite this, a patchwork of little Italian states had been unified into a new nation, a nation with ambitions to become a great power. Such ambitions would help lead to World War I.