Prehistory to c.3000 BCEUnit 1: Prehistory and the rise of Civilization to c.3000 B.C.E.

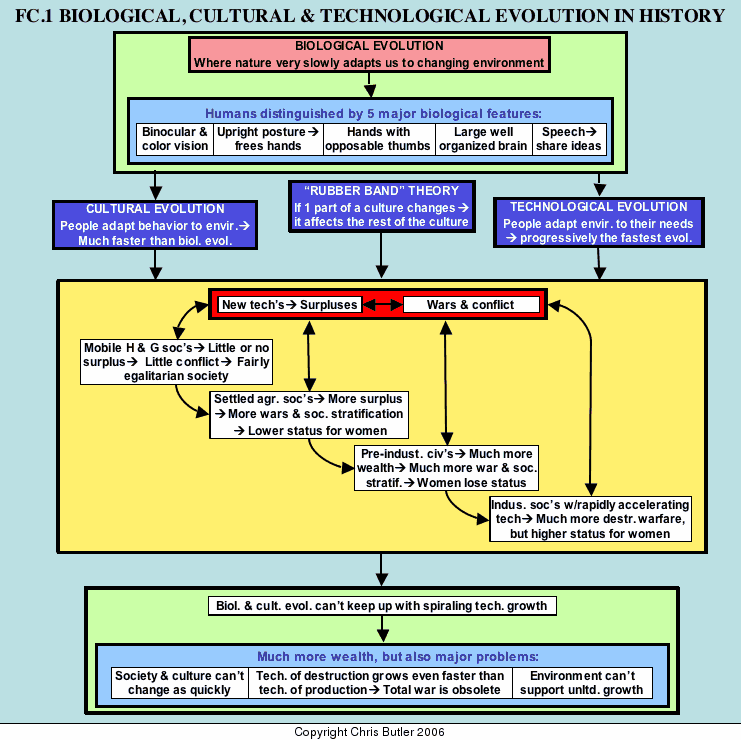

FC1Biological, Cultural, and Technological Evolution in History

Introduction

There are three types of evolution that have driven the development of human societies. The first of these is biological evolution where nature very slowly adapts us physically to our changing environment. Whether one believes in the theory of dynamic biological change and evolution or a more static creationist model of biology, one cannot deny we are biological beings with certain characteristics that largely distinguish us from other animals. There are five major characteristics that make humans unique. One is our binocular and color vision that gives us depth perception and a more detailed view of our surroundings respectively. This sends a lot of information to our brains for processing, making us very much a visually oriented species with 90% of the information we take in coming in through the eyes. Second we have upright posture, which frees our hands. This brings us to the third factor, our hands with opposable thumbs, which allow us to manipulate various objects and our environment. That in itself would be worth very little if it were not for the fourth characteristic, our brain that allows us to use our hands in intelligent and creative ways. The brain also makes possible the fifth characteristic, speech which allows us to share knowledge and ideas quickly so each generation does not have to rediscover that knowledge on its own, giving it time to discover and develop new knowledge and ideas.

This unique combination of biological characteristics is the basis for two other types of evolution: cultural and technological. One can see cultural evolution as how people adapt their behavior to the environment. Since these are conscious rather than totally random, or non-existent, changes, they occur at a much faster pace than biological change. However, the force of tradition typically keeps people from rapidly changing long-standing cultural traditions that generally have served society well in the past. This is because people through most of history have barely survived with little or no surplus, giving them little or no margin for error if the new change does not work, and making them reluctant to change cultural norms very rapidly.

Technological evolution enables people to adapt or change their environment to meet their needs. This is often something that can be done without immediately changing cultural norms. Therefore, it tends to happen at a much faster rate than cultural change. Not only that, but each new invention, being developed consciously and often based on previous successful inventions, is likely to improve the standard of living. This makes people more likely to develop new inventions, further improving their standard of living, and so on.

The “Rubber Band Theory”

One of the most important concepts to understand about history is how any particular event or development rarely has just one cause or just one result. Typically, if one part of a culture changes, it leads to changes in the other parts of the culture. One can visualize each part of a culture (social structure, political structure, technology, the arts, religion, economy, military institutions, etc.) as being connected to each of the other parts by rubber bands. If one part (e.g., the economy) changes and moves forward, it tries to pull all the other parts along with it. If any, some, or all the other parts do not move, the rubber bands connecting them stretch as the distance between them increases. If the distance and tension become too great, one or more of the rubber bands snaps, signifying some form of breakdown or dramatic change, such as a revolution.

An overview of the flow of history

The combination of cultural and technological change along with the Rubber Band Theory helps explain the overall flow of history. The process driving this comes increasingly from technological change. This leads to surpluses that lead, among other things, to wars and conflict since people have typically fought over material wealth. These surpluses and the wars they cause lead to efforts to find new and better technologies. These create even more surpluses and wars, more new technologies, and so on. Since there are more technologies on which to base new ones each time this feedback cycles around, technology growth continually accelerates in speed and intensity. This process has created four successive stages of development in human society, each of which feeds back into the cycle of technological growth, thus leading to the next stage.

First, through the vast majority of our species’ existence our ancestors followed a hunting and gathering way of life, with men typically doing the hunting and women gathering fruits and grains while watching the children. Such societies were highly mobile as they pursued wild game. They had little or no surplus and therefore virtually no private property since, being mobile, they could carry very little with them. By the same token, they had to be highly cooperative and share freely, since a man or the men as a group did not always bring home any meat and had to rely on what the women had gathered. All this made for a somewhat egalitarian society with little difference in status between men and women. At this early stage, with little previous technology to draw upon, new technologies developed slowly.

That changed somewhat with the next stage: the invention of agriculture (c.8000 B.C.E.). This forced people to settle down as they generated progressively larger surpluses. For the first time, people could amass private property, which led to different social classes distinguished by wealth. That in turn triggered conflict within the society and wars between societies. With survival based increasingly on brute strength, men emerged as the leaders and women’s status started to drop.

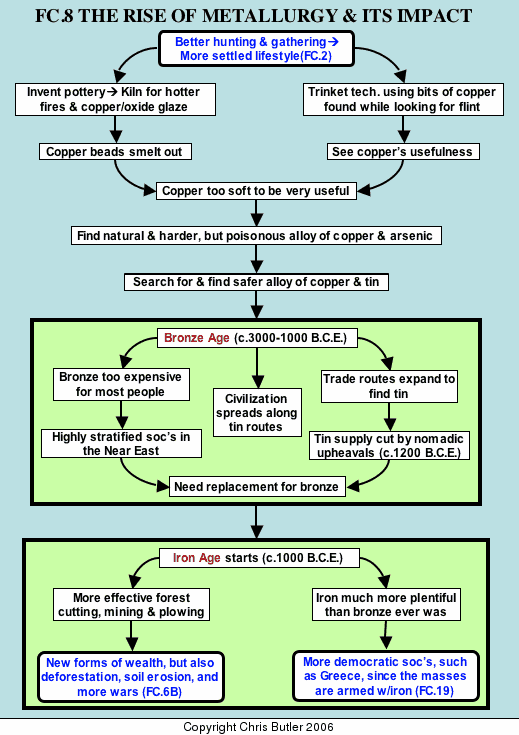

Social stratification and conflict accelerated during the next stage, pre-industrial civilization, which started c.3000 B.C.E. Two new inventions especially distinguished this stage. First of all, metallurgy, provided new forms of wealth and weapons with which to fight over that wealth. Writing helped people keep track of and amass larger amounts of wealth. More wealth led to wars of much greater intensity, frequency, and destructiveness. It also further reduced the status of women who had lost virtually all control over property by now.

The fourth stage, industrial society, started in Britain (c.1750) and has spread rapidly across the globe since then. This period has been especially marked by the rapid acceleration of technological growth. Unfortunately, this has been particularly true of military technology, which has increased the destructive power of warfare by several quantum leaps as seen in the two world wars which dominated the first half of the twentieth century. Ironically, the status of women has risen dramatically in industrial societies, largely because machines have reduced the need for or value of brute muscle, thus making women more competitive for jobs and opportunities, even in the military.

The challenges of modern society: the rubber bands stretched

Technology is a double edged sword that has helped generate by far the highest standard of living and longest life expectancy in human existence. But the spiraling rate of technological growth over the past 200 years has created progressively greater stresses on the “rubber bands” holding human society together. This is because, compared to technological growth, all the other aspects of society (social structure, religion, morals, etc.) are much more dependent for their rates of change on cultural evolution which, as mentioned above, is very traditional and slow. This growing gap between the rate technological change and that of other parts of society has created ever mounting stresses and strains, and continues to do so as technological growth continues to accelerate. These problems break down into three main categories.

First of all, most aspects of society, being more bounded by traditional rates of cultural change, cannot keep up with and adapt to the rate of technological growth. All too often, new technologies are introduced without studying or trying to anticipate their long-range effects. An example of this is the birth control pill introduced in 1960. While the Pill did free women from being burdened with large numbers of children, which was the goal of its inventors, few, if any, people gave serious thought to how the Pill would change people’s attitudes toward sex and marriage, or how that would affect the status of women and the raising of future generations of children.

A second problem lies in the unbelievable destructive power of modern weapons, in particular hydrogen bombs. Before the industrial revolution, the destructiveness of war was largely proportional to the number of men directly engaged in it, and the number of those men was largely determined by the relatively low productivity of the pre-industrial societies that had to support them over time. This put distinct limits on how long and destructive wars could be, thus giving societies time to recover. Modern warfare, however, is by no means limited by such factors. A relatively few men can launch devastating destruction upon the planet totally out of proportion to their numbers. The technology of destruction has grown even faster than the technology of production, making total war as we understand it obsolete.

Finally, modern technology has transformed our economy from being mainly concerned with producing enough for everyone to being concerned with selling all it produces. This has spawned a pervasive culture of materialism and consumerism heavily influenced by advertising. Modern economies rely on more sales and consumption and sales to make the money to expand their production, which requires more consumption, and so on. Given the vastly larger population that is involved in this cycle and the ever growing levels of per capita consumption, there is no way the environment can support this level of growth.

All this adds up to a fairly grim prospect for the future. However, we are an ingenious and adaptable species that could very well see us successfully through our technological adolescence. For example, during the Cold War the United States and Soviet Union did manage to avoid a catastrophic third world war. While we are not out of the woods yet, there is still hope while there are still some woods left for us.

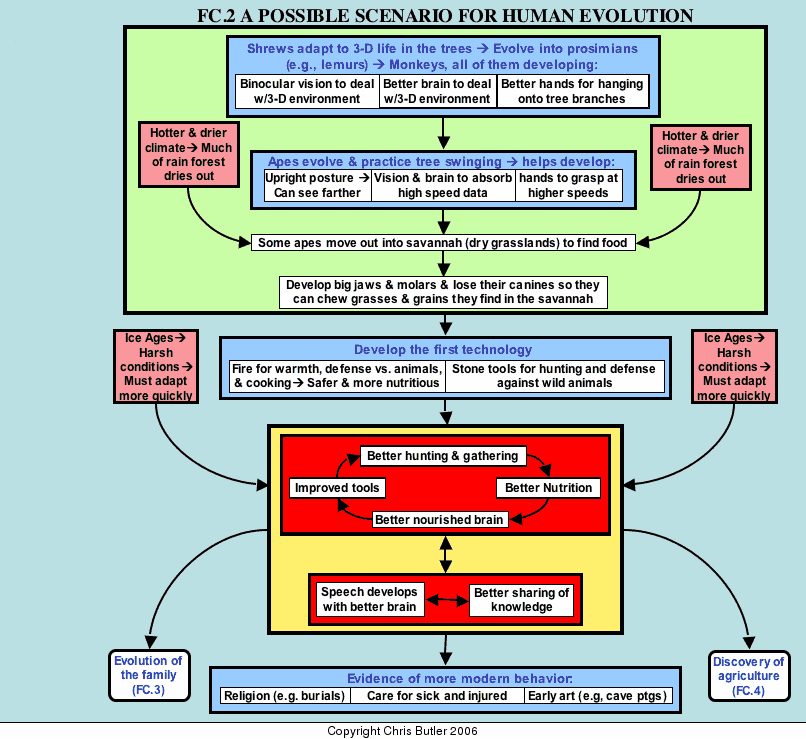

FC2A Possible Scenario of Human Evolution

Where to start?

While human history is primarily concerned with cultural and technological evolution, we need to understand a possible scenario for the evolution of the biological characteristics that have served as the basis for the human species’ other advances. Maybe a good starting point would be some 75,000,000 years ago. This is a mere drop in the bucket of time, but we have a long way to go before reaching anything closely resembling humans. We pick up our story with the lowly tree shrew.

The tree shrew, which appears quite similar to a mouse, hardly looks like anything we would like to call our ancestor. Yet scientists think this little creature was our connecting link with the lower forms of mammals. Converting this animal into a human would tax the skills of the most imaginative artist. It lacked binocular and color vision, upright posture, hands with opposable thumbs, a larger better-developed brain, and speech. In other words, it had none of the five characteristics that distinguish humans as a species. It also had to lose its tail, fur, and long snout.

The first critical step was moving into the trees away from intense competition on the ground. Life in the trees was more three-dimensional, involving accurately judging distances from branch to branch or else taking some nasty falls. This helped the development of binocular vision. Life in the trees also required hanging on to things to keep from falling. As a result, a primitive grasping hand started to evolve. Also, the more three-dimensional world of the trees required more awareness of things in all directions. This stimulated brain size and development.

Some 25,000,000 years later some tree shrews have evolved into the prosimians. These included the tarsier and ring-tailed lemur, which are often seen at the zoo and mistaken for monkeys. The prosimians resembled humans much more than the tree shrew, having binocular vision, shorter snouts, hands of a sort, and bigger brains. However, they still lacked erect posture and speech, while their brains, hands, and eyes fell far short of human standards. Some 40,000,000 years ago monkeys evolved from the prosimians. Although showing no obvious new developments toward human characteristics, they were more intelligent than prosimians and had better developed hands and eyes.

Next, we come to the apes, our closest cousins. Apes practiced one activity, tree swinging, that helped lead to human evolution in several ways. First of all, since tree swinging put the ape in an upright position, its head had to switch its position in order to see where it was going. A quadrupedal (four-legged) animal's head connects to the spine at the back of the skull. If we were to stand a dog on its hind legs, its head's normal position would have it looking straight up. The same was true for the still quadrupedal ape when it started tree swinging, making it more prone to crash into trees. Therefore, the ape's normal head position moved to connect to the spine at the base of the skull in order to adapt to this new tree swinging posture. This also paved the way for the later adaptation of erect posture that would free the hands for tool use. Speaking of the hands, tree swinging also led to more use and development of the hands giving apes better hand dexterity. The fairly rapid speeds at which apes swung also meant a lot of things came at them quickly and forced them to react quickly, thus leading to further brain development.

If apes had so much going for them, why did they not all evolve into humans? In general, one can say that evolution and natural selection are conservative and do not favor changes unless forced to by circumstances. This was especially the case with chimps, who had an easy niche in nature and felt no need to evolve. It was also true of gorillas whose great size let them stay pretty much the same. Timing was also important. Gibbons and orangutans were swinging in the trees for so long that their arms became over specialized for tree swinging and could not adapt well to life on the ground where our ancestors evolved. On the other hand, baboons came out of the trees too early and had not swung long enough to develop their upright posture. Thus they remained quadrupedal.

Out of the trees

Still, some three to five million years ago some apes did emerge from the trees into the African Savannah (grassland), and the question once again is why? The most likely answer is for food, and this is supported by the most plentiful and durable evidence we have from then: their teeth and jawbones. About this time their molars and jawbones got much bigger, suggesting they were eating lots of seeds and grains, which required massive jaws and molars to grind them up. This also meant that the canine teeth, their main defensive weapon in the harsh and dangerous Savannah, got in the way of chewing. Choosing between defense and eating, nature decided eating was more important and the canines were lost.

This of course created the problem of defense against predators. The solution seems to have been some sort of weapon. It was certainly nothing more than a stick, bone, or rock, but it apparently was effective. If it had not been effective we would not be here to talk about it. The importance of all this is that for the first time in the history of life on the planet, an animal was using a form of technology to extend its power dramatically and increase its chances of survival. The dawn of humans, or more properly, hominids had arrived.

The term hominids refers to modern humans (i.e., ourselves), our most direct ancestors, and collateral branches of our family tree that came to a dead end, such as the Neanderthals. . The earliest of these hominids, known as Australopithecines, lived from one to five million years ago. They were somewhat human in that they had better developed eyes, posture, hands, and brains than the apes. However, scientists do not generally call them humans because their brains were still much smaller than ours (about 450cc compared to around 1400cc for modern man). Their hands also had little or no precision grip, and they probably could not speak. Many see Australopithecines as the missing link between apes and humans.

There were several varieties of Australopithecines. The earliest, Australopithecus Afarensis, provided us with one of the most amazing discoveries in archaeology: forty percent of one skeleton. That may not sound like much, but it was unheard of to find that much of such an old skeleton intact. The scientist who found it, Donald Johansen, was so struck by this find that he even gave it the name Lucy after the Beatles song "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds."

Australopithecus Afarensis was the likely ancestor of two other branches of Australopithecines. One branch, the larger in size, was vegetarian. The other branch ate both meat and plants. The importance of this is that hunting for meat required more inventiveness than did collecting vegetation. As a result, the meat eaters developed tools (possibly including containers for better gathering) and weapons much more than the vegetarians did.

Eventually the meat eating Australopithecines evolved into what many scientists call the first true humans, Homo Habilis ("handy man") with a brain capacity of 650cc. They used and made very crude tools, although they still could not speak. For that reason, other scientists reserve the honor of the first humans for people known as Homo Erectus who had a brain capacity of some 750cc., which gave them the ability to speak.

Technological and cultural developments since the Australopithecines

A good deal of controversy surrounds the evolution of humans and their family tree. However, our evolution over the last million years has revolved increasingly around our technological and cultural innovations rather than biological changes. This is largely because on the one hand, biological changes are purely random, thus making evolution quite slow. However, technological and cultural changes are the products of more conscious and focused efforts to solve problems or create something. Therefore, such innovations happen at a much faster pace and accelerate the pace of change since they build upon previous efforts.

There were two main types of technological development our prehistoric ancestors came up with early on: flint tools and fire. Flint is unique among rocks because, when hit in the right way, it shatters, leaving very thin and razor-sharp pieces that can be worked into blades. Over time, as people spread to areas with little available flint or used up once plentiful supplies, they had to make more efficient use of this precious resource. At first, people were somewhat wasteful of it, maybe making only one hand ax out of a block of flint. It is estimated they got only 2-8 inches of blade for every pound of flint they used. Early Ice Age peoples came up with a method of knocking chips off of a piece of flint and using each chip for an ax or spearhead. As a result, they were able to get up to forty inches of blade per pound of flint. Their descendants would further refine this to get forty feet of blade per pound of flint.

Fire.

Of all the things that our ancestors invented or mastered to protect themselves from the harshness of the physical environment, none was more important than fire. As the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus wrote, it was the "brightness of fire that devises all” To the Greeks, it was the source of their crafts and civilization itself. It was what distinguished humans from the rest of the animal kingdom and gave them so much power; too much power as far as Zeus, king of the Greek gods was concerned.

The first people who mastered fire could use it, but probably not make it. As a result, they depended on natural sources such as a volcanoes or forest fires caused by lightning for their fire. Considering animals' natural fear of fire, we must admire the courage of that first individual who dared to pick up a burning ember and take it home. Once our ancestors had harnessed fire and found a way to keep it burning, they discovered some important uses for it.

The first use was probably for hunting and defense against wild animals, since it was obvious that animals feared fire. A common hunting technique would be to start a brush fire and use it to drive game toward other hunters or over a cliff. The value of fire for light and warmth soon became apparent, especially after our ancestors migrated out of Africa into the cooler climates of Europe and Asia. Fire could also harden sharpened sticks into better weapons. Finally, fire was useful for cooking food with several important results.

Cooked meat in particular held several advantages. The heat caused a chemical reaction that created proteins out of the amino acids in meat, thus making it more nutritious and leading to a healthier population. Fire also killed microbes in the meat, making it safer to eat. Finally, fire softened meat, making it possible for the very young and sick to chew it and thus be nourished. Altogether, cooking led to a healthier population that could grow and spread across the globe. We today are so concerned with overpopulation that we lose sight of how important and difficult it was to maintain a stable or growing population until very recently. Back then the average life expectancy was probably no more than twenty years, and half of all children died before the age of five. Thus extinction was a very real possibility. Cooking removed that possibility a bit.

The Ice Ages

Around 200,000 years ago, the planet started turning much colder. The cause of the ice ages is still unknown and subject of several theories including variations in the tilt of the earth's axis and its orbital path, continental drift, and clouds of cosmic dust blocking some of the sun’s radiation. Whatever the cause or causes, glacial sheets of ice moved south, covering much of the Northern Hemisphere. Summertime temperatures in England probably reached no more than 50 degrees Fahrenheit. By the same token, winters were horribly cold.

Such harsh conditions forced important changes in our ancestors and the various other life forms then. Keep in mind that physical adaptations were not planned or conscious. Rather, natural selection just accelerated the process whereby genetic mutations would be favored. What emerged was a whole new array of animals: giant cave bears, saber toothed cats, and woolly mammoths and rhinos to name a few. Our ancestors also went through some changes as well. Homo Erectus, as our prehistoric ancestors from then are called, had moved into cooler climates in search of game and living space. However, when the glaciers came, they were forced to adapt. What had been a fairly stagnant culture and species in stable conditions now changed at a relatively rapid rate. Even more rapid than their physical evolution was the evolution of their technology and culture.

Accelerated technological development

At this point, we see a cycle of technological development emerge to accelerate our evolution. Tool use stimulated brain development, which helped lead to more successful hunting and gathering. The improved diet and resulting brain development stimulated more tool development, better hunting, and so on. This basic feedback set in motion by hunting and tool use continued to repeat itself through the ages and is still at work today. Each new invention we come up with extends our power and also stimulates us to come up with more new inventions. This was a process that had started long before with the Australopithecines and continues now.

Speech

One of the effects of a bigger brain was the evolution of speech. This allowed both closer cooperation and more efficient sharing of information in such ventures as hunting. Therefore, each generation could easily learn the skills its ancestors had developed and perfected over the years instead of spending most of its time re-discovering them. This stimulated more brain development and ability to speak, encouraging more cooperation and sharing of knowledge, and so on. This feedback also fed back into and further accelerated the previous cycle of technological development, stimulating more sophisticated speech, etc.

However, there were severe limits to early humans' speech. For one thing, their pharynx, or voice box, did not drop enough to allow the full range of sounds we are accustomed to making now. As a result, their physical ability to speak was only about one-tenth of ours in terms of the sounds they could make and the speed at which they could make them. Their mental ability to speak was also severely limited. It takes a brain capacity of about 750cc to reach the ability to speak. Babies today reach that threshold between one and two years of age. Many prehistoric humans may never have reached that capacity. Or if they did reach the threshold of speech, they probably reached it much later in life than children today do. Combining that with their short life spans, prehistoric peoples had little time to develop anything profound to say, greatly impeding cultural and technological progress for a million years or so.

Better hunting and gathering technology. The Ice Ages also reduced the amount of vegetation available for gathering, thus increasing our ancestors’ reliance on hunting and develop more powerful weapons. When a better ability to speak combined with the process of each invention stimulating ideas for even more new inventions, a dramatic leap in technology and culture also took place. By 10,000 B.C.E., our ancestors, known as Cro Magnon but essentially Homo Sapiens Sapiens (i.e., ourselves) in a primitive setting, had learned to use other materials, notably wood, bone, and antler, in combination with flint, thus vastly expanding their range of tools and weapons compared to the crude and limited tool kit of the earliest hominids:

-

the use of bone, antler, and ivory for making tools that flint was unsuited for;

-

the sewing needle that led to warmer, better fitting clothes;

-

the spear which both extended the range and power of the hunter as a throwing weapon while maintaining a safe distance from dangerous animals when used as a hand held weapon;

-

barbed and grooved spearheads, which, being more deadly, led to better hunting;

-

the bolo for tripping up game;

-

the ability to make fire, giving them a stable source of warmth;

-

grooved air channels under the fire which led to hotter fires (which would lead to fired ceramics, which led to pottery and the kiln, and eventually to the furnace for smelting metals with all their contributions to civilization;

-

flint sickles, with bone or wood handles, which led to better gathering and a healthier population;

-

the burin, the first tool used for making other tools;

-

woven baskets, which also led to better gathering and more food;

-

fishing with spears, nets, and gorges (a type of hook), which led to a more stable food supply; and

-

crude shelters, built at first as wind breaks in the entrances of caves, and later as free-standing structures

Looking at all these inventions, Cro Magnons seem to tower over their ancestors, much as we see ourselves towering above them. This is deceptive, however, because we are building on what our ancestors built. Without the accomplishments of Cro Magnon and those who went before them, our own civilization could never have evolved.

All these new advances had profound implications for the future. For one thing, our ancestors’ larger brains would help lead to the development of the human family. Secondly, increasingly efficient hunting, gathering, and fishing made possible a more settled lifestyle, giving people time and opportunities to notice certain things around them, in particular the way seeds grow into plants. This revelation was the basis for the next great step in human evolution, the food producing revolution, or agriculture. Finally, better brain development and technology inspired and made possible new activities and behaviors that make the Cro Magnons seem much more modern to us.

Our ancestors’ behavior over the last 100,000 years or so also shows a much higher degree of intelligence than ever before. For example, they seem to have first realized the inevitability of death and created a religion to prepare for it. We have found people buried facing east and west, and also with the pollen of flowers in their graves. Our ancestors apparently worshipped the spirits of cave bears with whom they competed for living space. One Neanderthal cave has the skulls of some eighty bears arranged around it.

Prehistoric people also seem to have cared for their sick and infirm as evidenced by the skeleton of one man who lived to about forty years of age (old for back then) with the use of only one arm. They also apparently practiced female infanticide (killing female babies) as a form of population control. This is a comment not so much on our ancestors’ brutal nature as on the brutal conditions they had to deal with in order to survive. Not practicing such a measure might have meant extinction for the whole tribe or species.

Cro Magnons seem more modern to us culturally as well, especially in their art. In southern France and Spain they left a number of cave paintings that are amazing for their artistic touch and sensitivity. These paintings depict the various animals people then hunted. Their function may have been some sort of sympathetic magic in which portraying a successful hunt would cause a successful hunt. Whatever their purpose, these paintings are striking in the way they depict these animals in motion. They also can make us feel much more akin to these people we call our ancestors.

FC3A Possible Scenario for the Evolution of the Family and Gender Roles

The dramatic physical changes our ancestors experienced also triggered equally significant social changes that led to the evolution of the most basic social unit of our species: the family. One likely scenario involved two lines of development converging to create the family. First, as our ancestors moved out of the trees into the savannah in search of grains and grasses, they occasionally came across a carcass that they would pick clean for the meat. This casual scavenging gave them a taste for meat that developed into more intentional hunting. With the females tied down by the children, the males were generally the only ones free to hunt. Meanwhile the females and children would gather edible plants. Most likely, hunting was rarely successful, providing only about 10-20% of the food our ancestors ate, although the meat did provide valuable protein. The need to supplement the usually meager returns on their hunting may give us another clue as to why the males kept returning to the rest of the group. This pattern of food sharing created bonds vital to the evolution of the family.

Another development had to do with the evolution of a large brain and head which made the birthing process for humans more difficult. As a result, nature compensated by having human babies come to full term prematurely, making them among the most helpless animals at birth in all of nature. This greatly increased and prolonged children’s dependence on their mothers, who in turn needed protection and help getting food, especially in the harsh environment of the savannah.

The question is: why did males keep returning to the females and children? According to one theory, the answer lies in the evolution of year round mating in females to replace the seasonal estrus cycle that occurs in most mammals. The females who developed this pattern (by a purely random mutation) were better able to attract males to help them with food gathering and protection. As a result, more of their children survived to pass this characteristic on to future generations until it became the prevailing trait in humans.

Over time, these factors (year-round mating and food sharing) created permanent bonds that we have come to know as the family. Strengthening these bonds were two other factors. One was the added companionship and security of family life. We know, for example, that our prehistoric ancestors would feed and care for crippled members of their group despite their inability to contribute significantly to everyone else’s survival. Secondly, there was the emotional satisfaction that children gave their parents in terms of companionship, care in old age, and as an extension of themselves.

Gender differences in the species

For centuries there has been a controversy over the source of differences in male and female behavior and values within our species. Oftentimes described as the “Nature vs. Nurture” debate, it focuses on whether differences between men and women are the result of genetic or environmental factors. Coming largely from the Women’s Movement in the 1970s, the pendulum swung heavily to the side of nurture, the assumption being that aggressive tendencies in boys were the result of cultural factors and upbringing. The hope and belief was that if boys could be raised in an environment that didn’t stress aggression and violence, they would be no more aggressive than girls. Unfortunately, more recent research shows things are not quite that simple. While the environment is important in determining the way aggression is channeled, there are also inherent genetic factors influencing the equation. Testosterone levels in an individual are one factor. How men and women’s brains are structured is another. This may be the result of the hunting and gathering lifestyle our ancestors followed for the vast majority of our species’ existence and the different roles men and women played in it.

For men, who typically did the hunting, stalking and waiting for game required two main mental abilities: staying focused on one goal for long periods of time and keeping quiet during that prolonged period of waiting. This discouraged verbal socializing that could scare off any game. Nature would favor males whose brains were adapted to these qualities by awarding them successful hunts while killing off the more chatty ones through unsuccessful hunting and starvation.

Women, who performed very different tasks, required very different qualities. While looking for and gathering any edible vegetation, they also might have to keep track of several children and look out for predators. Unlike men, who had to stay quiet, those women who cooperated with one another (especially in looking out for one another’s children) and communicated verbally would be much more successful than women who operated quietly and independently of one another. For one thing, the sound of a number of women talking might be enough to scare off some potential predators. Such cooperation and communication would also create strong social bonds between the women, providing much of the glue that has kept societies together down through the ages. And just as nature would favor men with brains adapted to focus quietly on one goal, it would favor women whose brains were more adapted to verbal socializing and keeping track of several things at once.

Indeed, recent research has shown that men and women’s brains are largely structured in those ways. Women will typically use five times as many words in a situation as men will. Also, while men will listen with just one side of their brains, women will use both sides, indicating more of a talent for multi-tasking. It is important to note that these are general, not absolute, tendencies in men and women. Within each gender there is a wide range of differences between individuals, thus creating a large gray area that one certainly could not describe as absolutely male or female. Thus one should not use these general tendencies as supporting a “biology is destiny” argument for locking men and women into certain rigid roles. By the same token, these are tendencies we cannot afford to ignore in discussing issues of gender differences.

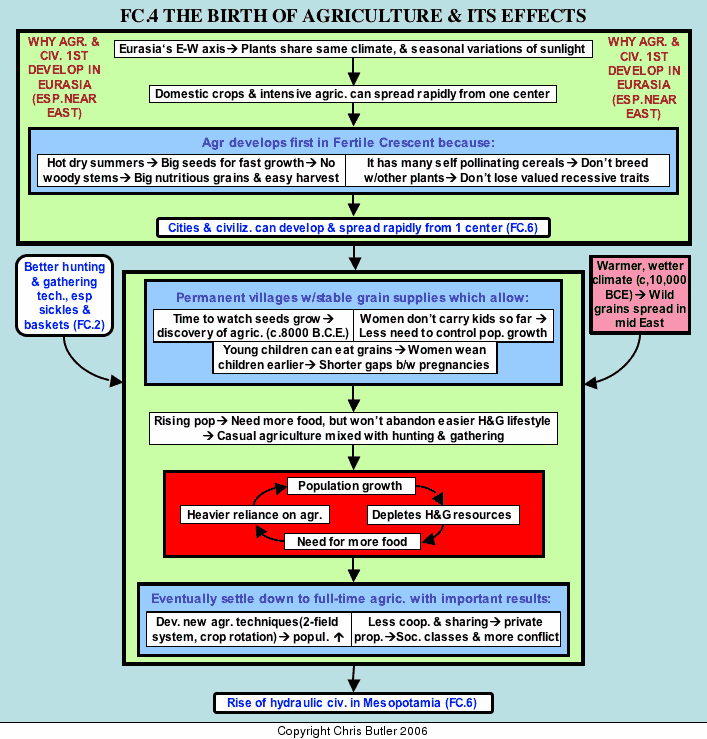

FC4The Birth of Agriculture and its Effects

Cursed is the ground for your sake; in sorrow shall you eat of it all the days of your life. Thorns also and thistles shall it bring forth to you; and you shall eat the herb of the field. In the sweat of your face shall you eat bread till you return to the ground; for out of it were you taken; for dust you are, and unto dust you shall return.(Genesis)

Introduction

Some 10,000 years ago, only 5-10,000,000 people inhabited the planet, certainly no more. Our ancestors’ technology had taken them a long way, but they still lived as part of nature, not in any way as its master. They did not realize it, but the last one per cent of our existence so far would see unbelievable changes sweep across the planet and change its face forever. Humanity stood on the verge of over-running the earth with vast numbers of its species. Supporting those vast numbers was possibly the greatest revolution in our history: agriculture, the ability for people to produce their own food supply. The agricultural revolution had two parts: the domestication of plants and the domestication of livestock.

Why Eurasia and Mesopotamia?

Starting with the birth of agriculture most of history’s major developments have taken place in the vast land mass known as Eurasia and extending across the Mediterranean and North Africa. Europeans who dominated the globe in the late 1800s and early 1900s claimed religious, cultural, and even biological superiority as the basis for their predominance. While such ideas hold little favor today, there still remains the question of why Asia and Europe have held central place in the history of civilization. Much of the answer probably rests in geographic and biological factors.

The underlying factor is that Eurasia lies along an East-West axis in mostly temperate zones. In contrast, Africa and the Americas are oriented from north to south and thus straddle a variety of climates. As a result, crops found in Eurasia are more adapted to the same diseases, climate, and seasonal variations in sunlight (which determine when plants germinate, flower, and bear fruit). Therefore, domesticated crops and intensive agriculture can spread more rapidly across Eurasia than they can across the vastly different climactic zones in Africa and the Americas. For example, because of intervening tropical zones, the cultivation of corn in the Temperate Zone of Mexico in the northern hemisphere never spread to Peru in the southern hemisphere until after 1500 when Europeans conquered both regions. Similarly, crops adapted for temperate zones in northern parts of Africa did not reach the southern tip of Africa until Dutch settlers introduced them in the 1600s.

Of course, there are also topographical and even climactic barriers within Eurasia, such as the Tibetan Plateau, Himalayan Mountains, and Asian steppes isolating East Asia from the rest of Eurasia. Therefore, agriculture probably developed independently in China and spread from there to Southeast Asia, Korea, and Japan. However, despite topographical barriers, the similar climates of East Asia and the western half of Eurasia ultimately allowed crop sharing in both directions, thus helping both civilizations advance more quickly.

Why Mesopotamia?

More specifically, it was Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) where agriculture first evolved in Eurasia and then spread westward across North Africa and Europe and eastward to the Indus River Valley. Environmental factors favored this specific region as the birthplace of agriculture. First of all, Mesopotamia, and the Middle East in general, have cool rainy winters and hot dry summers, encouraging plants, especially cereals, to develop large seeds for rapid growth in the limited growing season. This produces relatively small plants without woody stems, which, in turn leads to cereals with lots of large seeds (i.e., more food) that are easy to harvest (without woody stems).

Another factor is that Mesopotamia has many self-pollinating crops (six of them exclusive to that area) that can reproduce without pollination with other plants. The importance here is that recessive traits that are vital to farming but harmful to the plant in nature do not get bred out of the plant through cross-pollination. For example, along with the dominant trait for grains and pea pods to shatter in order to spread their seeds is a recessive trait for a few plants not to shatter. This made it easier for people to harvest them, plant more of them next season, and spread the varieties with the normally harmful tendency not to shatter.

Along with the spread of agriculture from Mesopotamia, other ideas and technologies could spread as well, leading to the relatively rapid development and spread of civilization across Eurasia compared to other regions of the globe whose environments prevented or greatly slowed down such exchanges. And, of course, after the impetus started by Mesopotamia, the exchange of new ideas became two-way, further accelerating the rise and spread of civilization in Eurasia.

The invention of agriculture

In addition to factors unique to Mesopotamia,two other converging factors led to the domestication of plants. First, better hunting and gathering technology provided a more stable food supply. Second, warmer and wetter conditions in the Near East at the end of the last Ice Age about 10,000 years ago led to the spread of cereal grains. Together these provided more stable food supplies that allowed people to settle down in more permanent villages. These villages produced two very different effects that together helped lead to the discovery and triumph of agriculture.

One was a growing population that needed more food than the hunting and gathering lifestyle could supply. This may have been partly due to earlier weaning of the young. Since women in hunting and gathering societies were always on the move, they could deal with only one highly dependent child at a time. Therefore, so they have only one small child to carry at a time, they would nurse their young up to age four to interrupt their fertility until their youngest child was less dependent on the mother. More settled village life made such strict birth control less mandatory, allowing earlier weaning and a higher birth rate as a result.

Settled village life also was gave people the opportunity to watch seeds in one place for a long time and notice how seeds grow into plants. Exactly how and when this happened is not known, but women probably made this discovery since they gathered the seeds and had more opportunity to notice how they sprouted and grew. Possible scenarios of this discovery include seeds spilled near camp or a wet grain supply sprouting and growing. However it happened, the realization of the potential of this discovery was probably gradual.

So was the transition to a completely settled agricultural lifestyle. While later civilizations would see agriculture as a gift of the gods, hunting and gathering peoples, such as the early Hebrews quoted above, saw it as a curse since it involved much more work and went against the traditional ways of life they had followed for countless generations. Whereas tradition today is generally shoved aside and scorned, we should keep in mind that until very recently, it was a major force in people's lives. They did not take change so lightly as we do since it disrupted the fragile stability of their lives. So the question arises as to why did people turn to farming.

The most likely explanation was they had to. For a long time after the discovery of agriculture, people continued to follow a hunting and gathering lifestyle mixed in with some casual agriculture, such as scattering seeds along a riverbank or in a field and coming back in a few months to harvest it. This did improve the food supply, and dramatically increased the number of people that could be supported. Even the primitive agriculture practiced then could support up to fifty times more people than hunting and gathering could. However, those extra people put a growing strain on the natural environment’s ability to feed them. One solution was to expand the agriculture. Of course, that led to more food and more population, causing even more strain on the natural food supply and leading to further expansion of the agriculture. In time, both men and women had to devote more and more time to tending the crops and less time to their traditional hunting and gathering ways. Eventually, they settled down and became full-time farmers.

Settled agricultural life had dramatic effects on human society and the environment. First of all, farming required less cooperation and sharing than hunting and gathering did. Before, all members of a tribe had to hunt together and share the results. Since there was no private property or anything to fight over, hunting and gathering societies were (and still are) relatively peaceful and harmonious. In contrast, agriculture allowed individual families to farm their own lands. As a result, private property evolved which led to social classes and more conflict in society between rich and poor.

New agricultural techniques, which replaced the more primitive slash and burn agriculture, also had their effects. The two-field system, which left one field fallow each year to replenish the soil, and crop rotation, which used different crops to take different nutrients out of the soil, reduced soil exhaustion. Both of these, combined with one other technique, irrigation, also created a surplus of grain and the need for a high degree of organization and cooperation. That surplus and level of organization in turn would lead to the rise of the first cities and civilizations with specialized crafts and technologies such as writing and metallurgy.

In the process of farming, our ancestors also inadvertently disrupted natural selection. There were two varieties of wheat they collected on the hillsides of the Near East. The dominant type shattered upon the slightest touch, scattering the seeds so the species could spread and survive. The other, recessive type, did not scatter its seeds so easily, and thus was harder to find. However, it was easier to harvest since the seeds did not scatter. As a result, a higher proportion of this variety was collected and planted than occurred in nature. With each succeeding year a higher proportion of the non-scattering wheat was harvested and planted. Natural selection had been reversed.

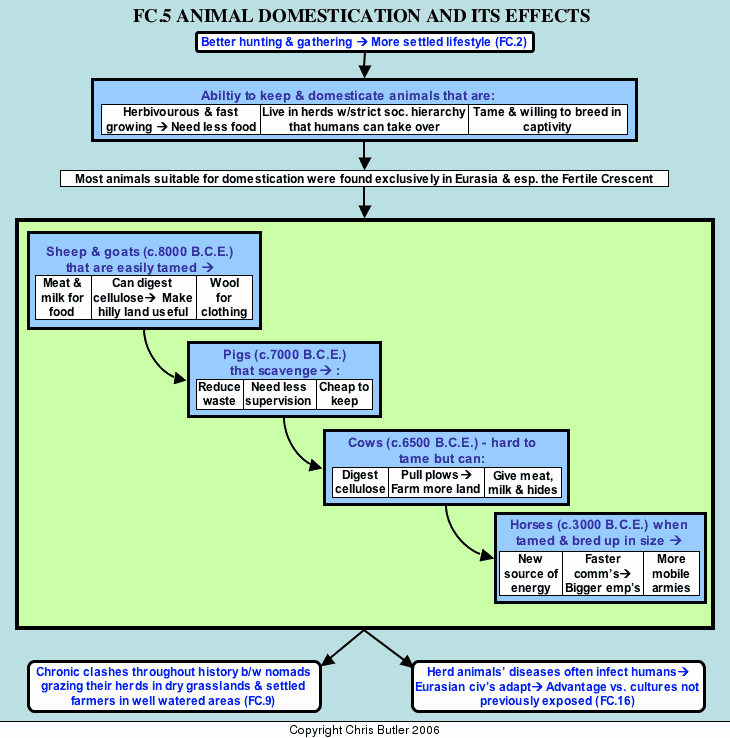

FC5The Domestication of Animals and its Effects

About the same time as the invention of agriculture (c.8000 BC) another revolution occurred: the taming of wild animals for domestic use. As with agriculture, the more settled lifestyle that better hunting and gathering allowed at the end of the last Ice Age was important, because it gave people the time and opportunity to keep and domesticate animals.

However, while animals of many different species have been tamed and kept as pets by humans, only a very few have been big enough (100 pounds or more) to be useful as sources of food and labor while meeting three basic criteria for true domestication. First, they must be herbivorous (plant eaters) and fast growing so they use up a minimum of our food resources and quickly become useful to us as a food source. Herbivores directly convert the plants they eat into meat, while carnivores require at least one extra level (i.e., other animals) in the food chain to survive. Therefore, pound for pound, it will take up to ten times as much plant nutrition to raise and support a carnivore as it does to for an herbivore.

Secondly, animals suitable for domestication should live in herds or packs with a strict social hierarchy of which humans can assume leadership. The third criterion for domestication is that animals must be easy to tame and willing to breed in captivity. This also rules out most carnivores, who are typically aggressive hunters and less easily domesticated than herbivores. An obvious exception is dogs who, being relatively small, must hunt cooperatively in packs, making them more social and easy to domesticate.

As with agricultural plants, what few animal species that are suitable for domestication are found predominantly in Eurasia and especially in what we call the Middle East of the Fertile Crescent. There were five such animals. The first two of these to be domesticated were sheep and goats, largely because they were the most docile and easy to tame. Sheep provided meat, milk, and fur. They also were ruminants, which meant they could digest the cellulose from grass, thus making previously useless land (e.g., rocky hillsides) useful.

As with plants, our ancestors also tampered with natural selection, using selective breeding to produce animals that were fat, meaty, slow, and with long wool rather than fur that is shed seasonally, qualities that are useful for us but normally harmful to a species in the wild. Eventually, this process would produce sheep and goats that differed considerably from their cousins in nature.

The next animal domesticated was the pig (c.7000 BC). Unlike sheep and goats, the pig was not a ruminant and providing no milk or fur. However, pigs did provide meat and, being scavengers, had several advantages. Whether scavenging in the local woods or city streets, they were cheap to keep. They also needed little or no supervision, making them easy to keep compared to flocks of sheep and goats that needed constant shepherding. Finally, until very recently, towns and cities rarely had proper sanitation facilities, making them extremely unclean and unhealthy. Pigs scavenging in the streets helped keep them a little cleaner. In fact, many towns had laws protecting them, despite their mean dispositions and occasional habit of attacking children.

Cattle were next (c.6500 BC), which gave milk, meat, hides, and could eat grass. However, they were bigger, wilder, and tougher to tame than sheep, goats, and pigs, causing some civilizations, such as the Minoans on Crete, to see the bull as a symbol of power. Probably the most innovative use for the cow was to hitch it up to a plow, tapping a non-human energy source that increased the power at our disposal and the amount of land under cultivation many times over. However, the earliest farmers hitched the plow up to the cow's horns, not the most efficient use of its power.

Somewhat later (c.3000 BC), horses were domesticated with three far-reaching effects. First of all, they could be used as a source of labor like cattle although their full potential wouldn’t be tapped until the invention of the horse-collar (c.900 AD) which pulled from the chest rather than the neck. Secondly, mounted warfare made armies much more mobile, dangerous, and destructive. This was especially true of nomadic horsemen who would occasionally be the scourge of richer and more sedentary civilizations. Finally, mounted messengers dramatically quickened communications, making it possible to keep in touch with and rule much larger empires.

Agriculture and domestication of animals created two basic types of lifestyle: settled farmers tending their crops and livestock in the richer farmlands, and nomads wandering with their herds of sheep, goats, and horses across the dry grasslands on the fringes of civilization. As we shall see, these two ways of life, nomads and farmers, have clashed repeatedly throughout history. We shall also see how the infectious diseases domesticated herds of animals carried would play a critical role in Eurasia’s dominance of the planet.

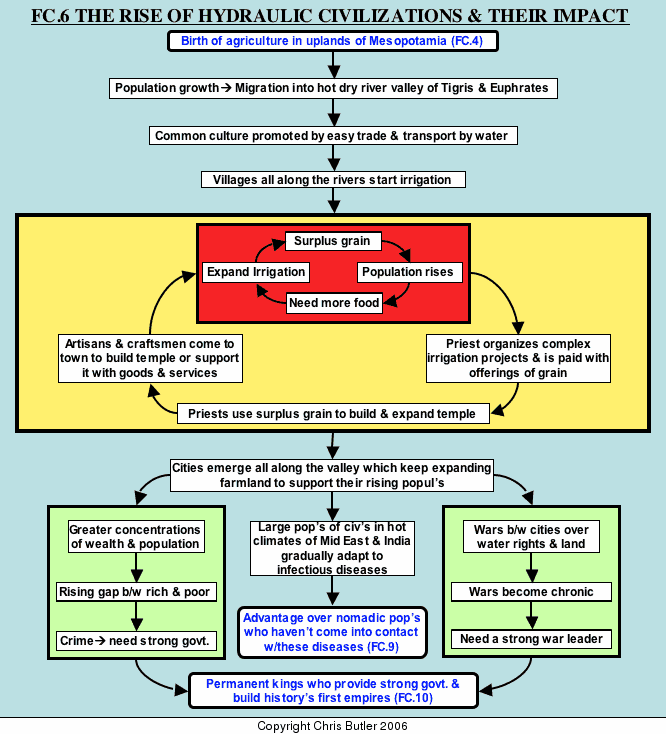

FC6The Rise of Cities and Hydraulic Civilizations (c. 8000-3000 BCE)

To a nomad, first encountering an ancient city must have been much like walking into one of our science fiction movies, only more incredible. After all, we have cities on which to base our concepts of science fiction movies. The nomad really had little or nothing to give him the idea for our ancient city. One should see what a remarkable leap forward it was when the human animal started changing the face of the earth with cities. If agriculture, with its surplus that frees other people for other pursuits, is the backbone of civilization, cities are its heart and soul. Cities are where those extra people congregate to practice the arts and skills of civilization: pottery, metallurgy, weaving, art, architecture, literature, commerce, and so on. Even the word civilization shows the importance of cities to it, since it comes from the Latin word, civitas, meaning city.

The earliest cities arose around 8000 B.C.E., soon after the birth of agriculture, although they do not always seem to have been dependent on farming to survive. The oldest know city was Jericho, dating back to c.8000 B.C.E., making it twice as old as the Egyptian pyramids. Jericho was a desert city, located around a fresh water spring and largely owing its existence to that spring, since traveling caravans would trade their goods to the people of Jericho for its water. Jericho probably had several thousand inhabitants, who were well enough organized to build a fairly impressive city wall, citadel, and reservoir and dig a moat out of solid rock. Another early city, Catal Huyuk, in modern Turkey, dates from about 6500 B.C.E. It was a religious center, living off of a combination of hunting, farming, and trade.

The rise of hydraulic civilizations

Isolated cities such as Jericho and Catal Huyuk did not create civilizations. That accomplishment depends on a number of cities spread out over an area and sharing a common culture: language, technology, religion, art, and architecture. The first civilizations arose along hot dry river valleys in Egypt, Mesopotamia, northwest India, and China. The importance of rivers to these civilizations has given rise to the term : hydraulic civilization, coming from hydra, the Greek word for water. Such rivers provided easy transportation and trade for people in their valleys. Such people traded goods and also ideas. In time, a common culture would emerge, as each village would tend to adopt the better ideas and techniques of its neighbors along the river. The rivers and the hot dry climate spawned another activity critical to early civilizations: irrigation.

Let us focus on Mesopotamia, where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers were the only reliable sources of water for farming. The fact that these rivers flooded annually gave the farmers the idea of bringing river water to their fields. At first, it involved nothing more than catching floodwaters and letting them gradually run back to the fields. In time, as the population and need for more farmland increased, the irrigation got more involved and complex. Such a project required a high degree of organization and cooperation, and that required leadership. Keep in mind, ancient peoples viewed rivers as gods. This meant that cutting into them and tapping their water supplies had religious implications. As a result, the local village priest supervised the irrigation.

In return, the priest would get offerings of grain and farm animals. Since these offerings were much more than he could consume himself, the surplus food served as the earliest form of "capital", that is wealth that can be invested in operations beyond what is needed for survival. Naturally, the priest put the "capital" back into his "business", building a bigger temple and storehouse to hold the extra grain and animals. This involved hiring extra accountants, builders, and guards who would settle with their families around the temple. Over time, the irrigation would lead to more crops, which led to more people, which led to the need to develop more farmland and irrigation. This, in turn led to more offerings and further expansions of the temple and the settlement around it. Once the town was large enough, craftsmen would move in who would provide needed goods such as pottery and tools to the temple's workers. Thus, a third level of population below those of the priest and their workers would emerge. Over the centuries, as the population, irrigation, and temple kept expanding, what was once a small farming village evolved into a thriving city gathered around the temple. Such a city would need or want wood, limestone, metal, and other goods that the area could not supply. As a result, some men would become merchants, traveling far and wide to trade the city's surplus for other goods. In this way, the city would grow even more populous and wealthy.

The long, continuous river valley of Mesopotamia meant that not just one village priest, but dozens were faced with the problems and rewards of irrigation. Thus, the process of cities growing up around temples was repeated over and over throughout Mesopotamia. Since the rivers tended to create a common culture, these cities resembled each other quite a bit in how they grew up and even in how they looked. For example, temple expansion generally took the form of building additions on top of the older temple. This gave the temples, or ziggurats as they were called, the appearance of pyramids. At this point, with dozens of cities united by a common culture springing up throughout Mesopotamia, we can say civilization has emerged. Its first people, the Sumerians, step onto the stage of history around 3000 B.C.E.

Civilization brought problems as well as blessings. For one thing, the continued expansion of population and farmland to feed it eventually led to cities clashing over new lands. With civilization came the first wars. Since priests were ill suited for fighting, they would choose a lugal, ("great man") to lead them in the fight. After the war, the lugal would be expected to resign his office. However, either because of ambition or the fact that another war was always around the corner, the lugal would keep his office. In time, he became a permanent official, the king, who led the city-state in war and administered justice in peacetime.

This often led to tension with priests who felt their own positions threatened. The temple (or, more technically, the gods) controlled most of the land. This often made the temple unpopular with the people, who looked to the king for protection. Eventually, the king would emerge as the most powerful figure in the city, although the temple would remain quite influential, still controlling much land, patronizing the arts, and acting as a grain bank and redistribution center during times of famine.

Another problem brought on by civilization was that the larger population of cities (sometimes 20-30,000) meant that people did not always know one another. This led to distrust and oftentimes crime. The influx of wealth also meant more clearly defined social classes since the wealth was not distributed evenly. This, plus all the different types of jobs being done, led to distrust and disagreement. Law codes had to be formed and courts of justice maintained, which also led to the need for a king's strong central government.

Cities and civilization also gave rise to new arts, crafts, and technology. Weaving was certainly one of the most remarkable crafts if we consider how much imagination it took to see a fabric in the fiber of the flax plant. Its importance should be obvious to anyone who wears clothes. Pottery was another craft of great significance. Sealed pottery jars could keep bugs and vermin out of peoples' food supply, preserving it in terms of quantity and hygiene. The rise of civilization also saw the evolution of two other types of technology vital to our way of life: writing and metallurgy.

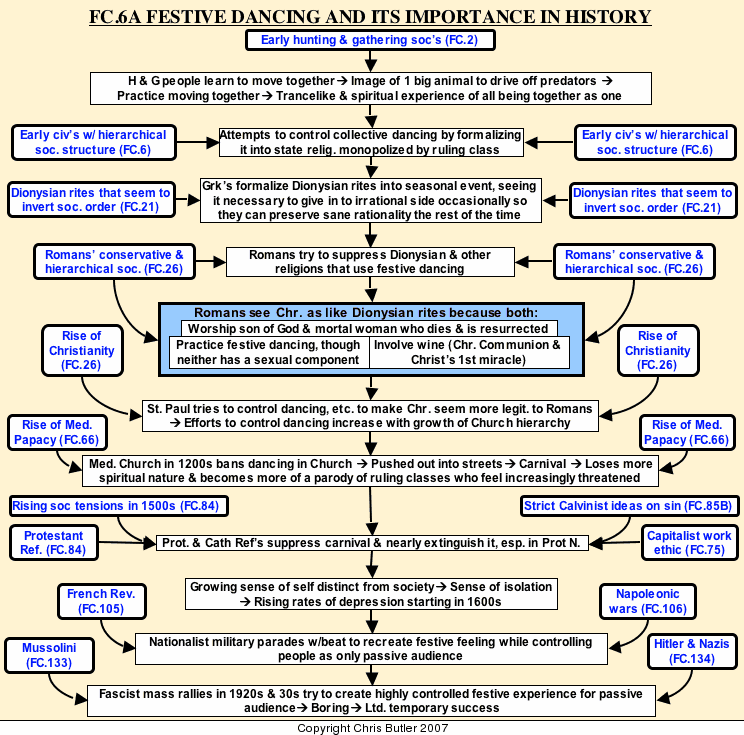

FC6A Festive Dancing and its importance in History

Introduction

One of the hardest aspects of history to document, yet maybe one of the most important, has been festive dancing. It seems especially remote to us, since we have become progressively more isolated as individuals since the industrial revolution, so we tend to lose sight of the importance of community in our lives. However, we are a social species that has relied on numbers to survive down through the ages, which brings up the question: what has kept us together all these years. The biological root of the answer lies largely in a pleasure center in our inner ears that likes a rhythmic beat.

Hunting, gathering, and dancing

Throughout most of our existence as a species, we have relied on hunting and gathering for our survival. Yet this was the time when our species was especially vulnerable and had to depend on the group for survival. One survival technique against large predators was for people to move together to make it seem that the predator was up against one big animal instead of a lot of small scared animals. Very likely, rhythmic community movement had its origins here, and either was based on or led to rhythmic dancing to celebrate or anticipate a successful hunt. When people practice moving together in time for a prolonged period, it induces a trancelike & spiritual experience of all being together as one. Besides being pleasurable, it also made our ancestors more effective in hunting as well as creating cohesiveness for the whole community in day-to-day life.

Early civilized dancing

When cities and civilizations evolved into societies containing many times more people than found in hunting and gathering groups, governments needed to provide the basis for identifying with and loyalty to these new states. Therefore they attempted to control collective dancing by formalizing it into state run religions monopolized by the ruling classes.

The cycle of religious dancing

At this point, we can see a cycle that constantly has repeated itself throughout history. Once the state or a ruling clique within a religion has taken it over, they tend to tighten their control by increasingly formalizing the religious rituals. By the same token, the religion becomes increasingly boring and uninspiring to its members. Therefore, some of them start a new sect from within that religion or a new religion comes along, either of which incorporates festive dancing in its rituals, attracting large numbers of new followers. The new faith or sect grows in numbers until some of its members feel a need to impose some order by rigidly formalizing the rituals. Eventually this religion of sect becomes boring and the cycle goes on.

In Western civilization we can see this cycle repeating at least four times. The first time had to do with the wild Dionysian rites spinning off from the Greeks’ state religion of Olympian gods. Euripides’ play The Bacchae gives us a somewhat frightening scenario of what happens when the king tries to suppress these rites, and the Maenads, formerly mild mannered women who are caught up in the frenzy of the Dionysian worship, literally tear him apart. To their credit, the Greeks realized that to maintain our normal rational ways of living, we must occasionally give in to our irrational passions. Therefore, they incorporated and formalized the Dionysian rites into state festivals. One aspect of these festivals was Greek drama, such as Euripides’ play discussed above.

The cycle next repeats in the early days of the Christian Church. The Romans, being a bit more conservative than the Greeks, had severely limited the practice of the Dionysian rites. Unfortunately, they saw Christianity in the same light as the Dionysian rites, since both worshipped the son of a woman and god who had died and been resurrected, and both practiced wild, although typically asexual, rites. Therefore, St. Paul, in an effort to dissociate his religion from the Dionysian rites and make it look legitimate to the Romans, tried to control the festive dancing. As Christianity grew in popularity and a hierarchy of bishops and archbishops evolved, Church leaders continued efforts to calm down its services.

During the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the Church had gone through a major religious revival, largely from the grassroots level of the monasteries, and emerged as the most powerful institution in Western Europe by 1200. In order to gain more control over its more enthusiastic members’ practices and beliefs, it banned dancing in church. However this only pushed the dancing out into the streets where the Church had much less control and evolved into Carnival, the festival that precedes the period of Lent leading up to Easter. At first, Carnival may have had some spiritual aspects, but it soon evolved into an excuse to indulge in the various activities banned during Lent, to satisfy any desire for those activities for the next forty days leading up to Easter. Among those activities was eating meat (thus the word carnival as in carnivore) and festive dancing. Carnival also largely became of parody of the Church and ruling classes, who naturally felt somewhat threatened by it.

By the mid 1500s, Northern Europe was in the midst of another religious revival, the Protestant Reformation. At this time, Carnival was still being celebrated in the North, when it ran into two obstacles. One was the puritanical idea, especially associated with the Calvinists (AKA Puritans in America), that most any kind of pleasure was evil. At this time Europe was undergoing major shifts away from a land based to a money and credit based economy. Such shifts always leave some people behind, in this case the peasants, and generate social tensions that occasionally turn into armed rebellions. Therefore, the authorities in the North suppressed Carnival, but with some disturbing results. There is evidence by the 1600s that being deprived of communal dancing was creating a sense of isolation in people with a corresponding rise in depression.

Fast forward to the period of the French Revolution in the late 1700s. A new secular idea was sweeping across France and then Europe: nationalism, which united peoples with a common language, history, and culture into that giant collective consciousness called the nation. The revolution’s leaders the importance of communal celebrations in bringing people together and actively promoted civic festivals to unite the people behind their leadership. When Napoleon seized power in 1799, he repeated the mistake of trying to control and structure such celebrations from above with military parades that had a stirring beat, but reduced the people to being a passive audience. The idea was to replace the horizontal social bonds between the people on the same level with a top-down bond between the people and their leader who was supposed to embody the very nation itself. The result, however, was to seriously reduce the impact of such events on creating social bonds among the people.

The pattern would repeat itself again in the 1920s and 1930s in Fascist Italy and Germany with the extra twist that Mussolini and Hitler in particular had modern loudspeaker systems that allowed them to stage-manage huge spectacles with thousands of people attending. These events did use rhythmic chanting of slogans to create some communal feeling, being reinforced by another psychological phenomenon of losing one’s individual identity in such huge crowds. However, the predominantly passive role played by the masses could soon make these stage-managed rallies seem boring, giving them limited success in the long run.

After the end of World War II in 1945, accelerated urbanization, suburbanization, and the tendency to move to a new neighborhood or city every few years have created new subdivisions, but not communities, which require generations to sink the deep common roots that truly unite people. Instead, mass media, especially television, has largely replaced community events in which people are actively involved. Television watching is a fairly solitary activity where it is rare for whole families to watch the same program together. Television may provide us common cultural reference points, but it doesn’t give us community. This lack of community seriously inhibits people from participating in common activities such as festive dancing. In fact, the idea of even trying to start such events on just a neighborhood level would seem laughable, so far have we become cut off from our cultural roots and each other.

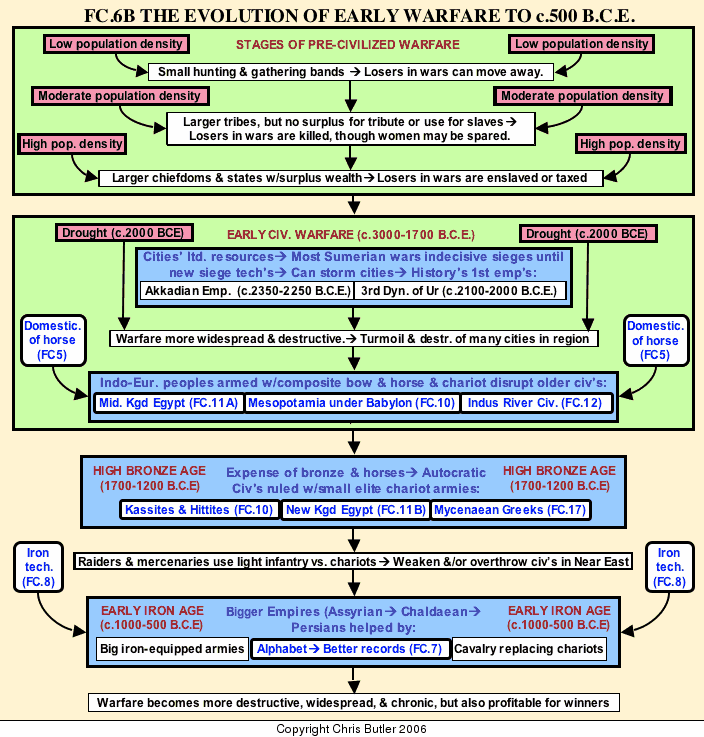

FC6BThe Evolution of Early Civilized Warfare

Introduction: the roots of warfare

Stages of pre-civilized warfare

Warfare in the early Bronze Age (c.3000-1700 B.C.E.)

Then sometime after 2400 B.C.E., a new siege weapon, the battering ram, was developed, which literally pulverized city walls. Now invaders could either directly occupy and tax subject cities or sack and destroy them. This made possible history’s first empires: the Akkadians (c. 2350-2250 B.C.E.) and the Third Dynasty of Ur (c.2100-2000 B.C.E.).

One factor that has affected the frequency of wars has been climate change, such as the drought, which hit Mesopotamia around 2000 B.C.E. As food and resources shrank, conflict over what was left intensified, both in terms of frequency and brutality. Warfare was also more widespread and destructive, leading to fewer resources as irrigation systems fell into disrepair, causing more wars and so on.

Around 1800 B.C.E. Indo-European nomads came down from the north with a deadly combination of two weapons: the composite bow and the horse-drawn chariot. Together these weapons gave them vastly increased mobility and firepower, as well as the initial terror inspired by horses, hitherto rarely if ever seen in the civilized world. One kingdom after another collapsed like a house of cards before the onslaught of these nomads with their terrifying beasts. People known as the Hyksos conquered Lower Egypt, while the Kassites overthrew Babylon, and the Aryans moved into the ruins of the Indus River Civilization.

The High Bronze Age (c.1700-1000 B.C.E.)

Sometime around 1200 B.C.E., everything came unraveled for these civilizations, once again because of how they, and their enemies, fought their wars. Much of the advantage chariots gave their owners in war was psychological. Thus battles were typically fought between two elite groups of charioteers while the mass of infantry stood by and watched. However, typically behind each chariot was a lightly armed runner who would rescue their downed charioteers and finish off those of the enemy. Such runners, oftentimes foreign mercenaries, came to realize the vulnerability of chariots to lightly armed infantry throwing javelins to bring down both charioteers and their horses. Armed with these tactics, these peoples either weakened or overthrew the big empires and kingdoms of the day. Although Egypt barely survived, the Hittite Empire, Mycenaeans and Kassites collapsed, allowing the victors to sack and plunder the riches of these civilizations. The Trojan War, immortalized by Homer, also took place at this time. A period of chaos prevailed for the next 200 years, when a new metal ushered in a new age in warfare and empire building.

The Early Iron Age (c.1000-500 B.C.E.)

Iron also revolutionized warfare, since states could afford to field much larger armies. Two other factors helped in empire building. One was the phonetic alphabet, which allowed governments to keep much better records on such things as taxes, thus giving them much tighter control over their subjects. The other factor was mounted cavalry replacing the more cumbersome and fragile chariots that needed a much flatter surface on which to operate. Mounted messengers also kept rulers much better informed on news such as invasions, allowing them to defend and expand their empires by a factor of several times. Therefore, the Neo-Assyrian Empire (934-609 B.C.E.) was three times the size of any previous empire. And the Achaemenid Persian Empire (550-330 B.C.E.) was several times larger still. Besides helping build big empires, iron equipped armies would have a radically different political effect: namely, the rise of democracy among the Greeks.

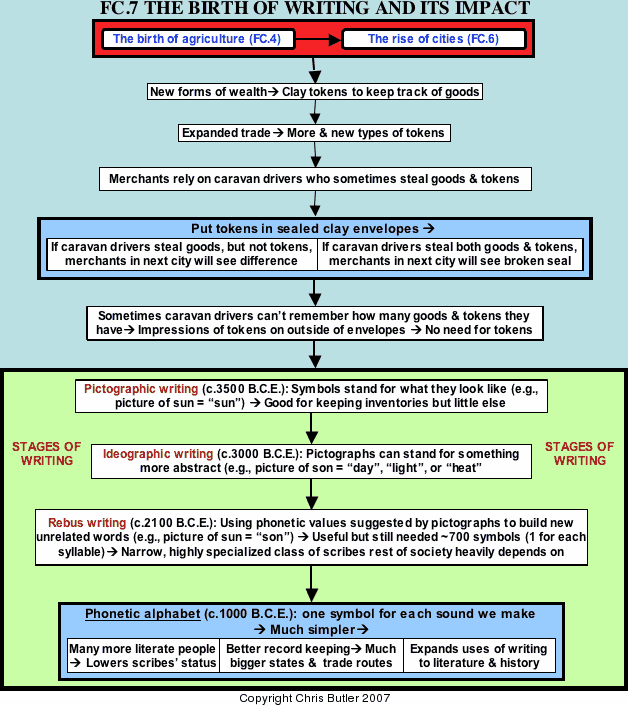

FC7The Birth of Writing and its Impact

Like so many other aspects of our civilization, we take writing for granted since we grew up with it. Therefore, consider the story of John Cremony, an army officer in the American southwest writing a letter to his mother back home. A Navajo Indian saw Cremony writing the letter and asked what he was doing. Cremony replied that he wrote words on the paper and sent it home. His mother would look at the paper and get his message. The Indian just laughed at such a ridiculous story. Therefore, in order to prove his story, Cremony wrote a note and told the Indian to take it to another officer who would read it and give him a piece of candy. The Navajo took the note to the officer who read it and, to the Navajo's astonishment, gave him a piece of candy.

Before we condemn the Indians or anyone else for not having writing, we should keep in mind that no one thought of the idea until about 5000 years ago. At that time, the first civilizations were emerging, and with them, a much more complex way of life. The temple of the Sumerian city of Lagash provides a good example. It employed some 1200 people, including 300 slaves. The temple employed 205 cloth workers in addition to sailors, millers, bakers, cooks, guards, fishermen, herders, and scribes. Such a complex operation was beyond one man's ability to keep everything straight in his head. A more efficient record keeping system had to be developed.

Prelude to Writing

People used to think that writing developed overnight in response to the needs of civilization. Actually, it gradually evolved with the increasingly complex society that started to develop with agriculture. At that time, people started making little clay tokens in various shapes to represent the types and numbers of goods they possessed. For example, a man might have ten small clay discs or one large disc to represent the ten bags of grain he owned. It was such a simple system of record keeping that sometimes the tokens had holes in them and were strung together in a necklace.

Around 3500 B.C.E., cities and much more complex economies were evolving. As a result, we find the number of types of tokens expanding dramatically as new types of goods were being produced and traded. Long distance trade was also starting with merchants and temples sending caravans with large amounts of goods from city to city. The caravan drivers would be entrusted with tokens representing all the goods they were travelling with. They would present the tokens along with the goods to a merchant in the next city after making a transaction. Unfortunately, it was apparently easy for the caravan driver to steal a few goods and the tokens for himself without the first merchant knowing he had done that instead of selling them honestly. As a result, the first merchant started putting the tokens in a sealed clay ball or envelope. If the second merchant found the seal broken, he knew the goods had been tampered with. However, the sealed envelope made it difficult for the caravan driver to remember how many items of each type of merchandise he was travelling with. Therefore, the merchant started making impressions of the shapes of the tokens on the outside of the clay envelope while it was still wet. Before long, someone realized that the envelope and tokens were not needed as long as there was an impression of them in the clay. The tokens were dispensed with, the envelope was flattened into a tablet, and writing was born.

Different stages of writing

Writing was first developed for keeping records of goods. In time its uses expanded, and that meant new ways to express and interpret the symbols had to be developed. There were five basic stages in the history of writing.

-

Pictographs(c.3500 - 3000 B.C.E.). In this stage, one pictograph or symbol means what it looks like. For example, a picture of the sun means the "sun". This stage was well suited for straight record keeping, but little else.

-

Ideographs(c.3000 - 2100 B.C.E.). Here the symbols can also mean something a bit more abstract than their literal meaning. A sun can mean "day" as well as "sun". A picture of legs can mean "legs" or "walk". Thus the uses of writing were greatly expanded, although there are severe limits on what one can write this way.

-

Rebus writing (c.2100 - 1000 B.C.E.). This was a critical turning point. Up till now, one related to what the symbols looked like to tell the meaning. With rebus writing, one used the phonetic sounds of words created by symbols to create new words. For example, a word like "Neilson" would be very difficult to write with pictographs unless everyone knew what Neilson looked like as distinguished from other people. However, with rebus writing, one could use the sounds suggested by a picture of a man kneeling plus a sun to build the word "Neilson". Rebus writing, by making the reader relate to the ears, not the eyes, made it possible to write just about anything. It was a complex system, however, since it required hundreds of symbols, one for each syllable used in a language. Both Mesopotamian cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphics used about 700 symbols.

-

Phonetic alphabet (c. 1000 B.C.E. to the present). This system is based on the fact that we can only make about twenty-five or so different sounds, while we can combine those individual sounds into hundreds of symbols, each requiring a different rebus. The alphabet simplifies the process vastly by using just one symbol for each individual sound we make (e.g.--B, D, K, etc.). Although we generally give credit for the alphabet to the Phoenicians (thus the term "phonetics"), it seems the Egyptians also had an alphabet of sorts that the Phoenicians drew upon. The Greeks completed the process by adding vowels, which the Egyptian and Phoenician systems lacked.

Along with writing, mathematics also evolved to help keep records. The Mesopotamians in particular had some sophisticated math, using base 60 instead of base 10 which we use. Mesopotamian influence is reflected even today in our 360-degree circle with 60 minutes in each degree. They seem to have developed the Pythagorean theorem for figuring out the lengths of the sides of a right triangle. They also figured a number of square and cube roots. The ancient Greeks, who gave us much of our math, drew heavily upon the Mesopotamians for their math.

Scribes and education

Before the invention of a much simpler alphabet, only a small group of men had the time to learn how to read and write a system using some 700 symbols. These men were known as scribes.